Running head: THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING

Running head: THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 1

The Water Cycle: Impact of Teaching Seventh Graders

EXPS 420 Science Capstone

Dr. Otto

University of Michigan – Dearborn

Elaine Bechard

Steven Pascoe

Lucy Zahor

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 2

Abstract

As pre-service teachers, we had the opportunity to conduct an action research project. Our goal for this project was to address student misconceptions on the water cycle while incorporating models based science teaching. We conducted this research in a 7 th

grade class in a Detroit

Public School. First we researched existing articles related to the water cycle and scientific models in an effort to create and administer a pre-assessment. We looked at the results from the pre-assessment data and made note of the students’ misconceptions. From these misconceptions we created two inquiry-based science lessons. After teaching the lessons we administered a postassessment test that was identical to the pre-assessment. After comparing the pre and postassessment data, we found that only 18% of our total responses were correct on the preassessment and this increased to 34% on the post-assessment. Some of the specific misconceptions that we saw in the pre-assessment were no longer present in the post-assessment.

We concluded that our inquiry-based lessons were beneficial to student understanding of the water cycle and of scientific models. Therefore, we can state that more inquiry-based lessons at the middle school level will continue this upward trend of student success.

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 3

Introduction

Research Question: What is the impact of our teaching 7 th grade students about the water cycle and models?

In our action research project, conducted in a 7 th

grade science classroom, our group is looking to gain insight and teaching experience in order to answer the above research question.

The research question for our action research project is connected to the “big idea” of models in several ways. As mentioned in the question itself, models will be the vehicle we use to teach the water cycle to the 7 th

grade class. Models can be used to show ideas and demonstrate phenomena as we teach. While we use these models, the students in the classroom will be developing models of their own, whether these are mental models or expressed models. We want to explore how student understanding of both the water cycle and of models changes as a result of our teaching, and how the two ideas can be connected.

The topic of the water cycle and the “big idea” of models can be connected to the Grade

Level Content Expectations (GLCEs) for earlier and later grade levels (compared to the seventh grade) (State of Michigan Department of Education, 2007). The topic of the water cycle and all of its related components is covered across a variety of grade levels. For example, in the sixth grade, students look at changes in states of matter (State of Michigan Department of Education,

2007). This is related to the water cycle as water freezes, melts, and evaporates at different points in the cycle. Also in the sixth grade, the impact of living organisms on the environment is discussed (State of Michigan Department of Education, 2007). The water cycle is affected by living organisms, such as transpiration by the plants, contributing to the amount of water vapor there is in the air. Human activity can also affect the water cycle, as we consume and use water.

We expect students to have an understanding of how water changes states, how living things can

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 4 impact the water cycle, and also be able to recognize the three major processes in the water cycle: evaporation, condensation, and precipitation. In later grades, (although the GLCEs do not continue past the seventh grade) as conservation and ecology are further explored, the water cycle can once again be brought to the forefront. Through the course of our action research in the classroom, we will discuss the water cycle as a way that the Earth conserves water and discuss the importance of human water conservation as it relates to the water cycle.

The “big idea” of models relates to the vast majority of all of the GLCEs for any grade.

Whether we are exploring the water cycle or animal cells, we can use and develop models for exploration and understanding. Students will also be developing mental models or creating their own physical models of the topics discussed, such as making a model of an animal cell out of

Styrofoam® or drawing a diagram of the water cycle. Both of these are models that can help the students gain a greater understanding of the science topic. Models are related to and used in all grade levels for a variety of topics. As it relates to the water cycle, in the first grade, students may use a model to look at precipitation changes, such as photographs. In the seventh grade, students may use models, such as a sponge, to examine how this precipitation can infiltrate the ground and enter the ground water supply. Models are a vital means of teaching and understanding science across all grade levels.

To prepare for our action research, we conducted related research on our topic and students misconceptions. The article by Henriques (2002) reviews existing research regarding children’s misconceptions of the water cycle. She begins by looking into the National Science

Education Standards to see what students are expected to know (Henriques, 2002). The review looks at a wide range of ages, and the children’s ideas and misconceptions regarding many science ideas, but our group focused on children’s ideas related to the water cycle. The study

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 5 shows that younger students think of the water cycle in terms of water freezing and melting

(Henriques, 2002). This is more of a lack of in-depth knowledge than it is a misconception.

Students across the grade levels have varying ideas regarding clouds and cloud formation.

Students see clouds as only composed of water evaporated from the sea, as a large sponge holding water, as large puffs of cotton, or of smoke (Henriques, 2002). Henriques then goes on to explain that misconceptions can be used as a starting point for instruction and that a list of misconceptions, like the one provided in the article, can be an important resource for a classroom teacher who does not have the time to probe for possible misconceptions in their students.

This article strongly relates to what we are doing in our action research project. We are teaching two lessons regarding the water cycle, but first we need to know students’ thoughts about the water cycle. This will be done through a pre-assessment, in which we ask students about topics such as cloud formation, and different components and processes in the water cycle.

As is mentioned in the article, we will then be able to draw out misconceptions and discover what the students know and do not know and use this information as a basis for instruction

(Henriques, 2002). Unlike the article by Henriques, which is designed to be used as a resource for teachers –simply stating different misconceptions– we will be instructing students with inquiry lessons in order to correct some of these misconceptions and educate the students about topics they were unsure about. By pre-assessing and post-assessing, we can see what affects our teaching had on student knowledge of the water cycle, something that was not done by

Henriques.

The second article that we reviewed was of a different type than the misconception-type articles. Our group wanted to research an article to be used for background information about the water cycle so that we could become more familiar with the topic ourselves, before we go to

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 6 teach the seventh grade class about the water cycle. The article by Graham, Parkinson, and

Chahine (2000), discusses the water cycle in-depth. We do not plan to have our action research project go beyond or make further contributions to this article; instead we hope to use it as a source of background information on the topic. The article provides assorted water cycle diagrams, discusses where the water on Earth is located, and also discusses each process within the water cycle, like evaporation, condensation, and precipitation (Graham, Parkinson, &

Chahine, 2000). We can use this article to develop pre-assessment questions or as a resource to use when evaluating student answers to these questions. It may also be valuable when we write our lesson plans, as we can once again gain valuable background knowledge on the subject of the water cycle to discuss in the explain portion of our 5-E lesson plan. A 5-E lesson plan is an inquiry-based science lesson involving 5 phases of instruction: Engage, Explore, Explain,

Extend, and Evaluate. This form of inquiry is largely student-based and requires students to be active participants in the learning process.

Through our research through education journals, we found additional articles that dealt with misconceptions about the water cycle. While on the same topic, the two articles gathered information differently and even sampled a very different group of students. The first article, by

Cardak (2009), used student drawings to find misconceptions whereas the other article, by Bar

(1989), asked students specific questions and recorded student responses.

In the article by Cardak (2009), Turkish students studying science were used as a source of data. The introduction to the article explains the importance of finding misconceptions in student thinking. The article states that misconceptions are formed by students’ own understanding of the world around them and are scientifically inaccurate most of the time.

Furthermore, the article states that student misconceptions can hinder the acquisition of new

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 7 knowledge if they are not first broken and compensated (Cardak, 2009). In the study, the university students were asked to draw the water cycle on a blank piece of paper. The pictures were scored on a 5 level system; level 1: no drawing; level 2: Non-representational drawings; level 3: drawings with misconceptions; level 4: partial drawings and level 5: comprehensive drawings (Cardak, 2009). Afterwards, students whose drawings depicted misconceptions were interviewed to verify the interpretation of the drawings.

This method, though used for university students, is still very much age appropriate for

7 th

grade students. This method of assessment for misconceptions allows us to see a student’s mental model of the water cycle. Our research can expand on this research by showing if the same misconceptions are present in earlier grades. Our research can also show how misconceptions have changed over time with more education, or unfortunately, how misconceptions that were present in late elementary grades are still present even until the final years as an undergraduate science student. Also, our project can compare the misconceptions that science students hold in different countries. While the article student sample was from a Turkish university, our project will focus on 7 th

grade students from Detroit.

Our student sample will better match the ages of the students in the second article by Bar

(1989). The age range for this article was five to fifteen years old and the students were Israeli.

Her students were from “advantaged backgrounds, coming from middle or upper middle class”

(Bar, 1989, p. 484). Bar makes note of the mental models the interviewed children had about the water cycle. For example, some students include smoke in their mental model of a cloud. Bar then elaborates as to why some students may have these misconceptions based on research by

Piaget, a leading developmental psychologist who studied how children learn.

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 8

Our project can expand on Bar’s research by comparing misconceptions held by middle class students in Jerusalem to low socioeconomic status students in Detroit. Our research can help evaluate whether or not socioeconomic status contributes to the types of misconceptions students hold in their mental models of the water cycle. Also, Bar had more children aged 5 to 9 than 10-15. Our student participants could add to the data collected for the smaller group.

While looking into more related research, we found some similarities in results. A group of researchers from Harvard University (Grosslight, Jay, Unger & Smith, 1991) asked students from ages 11-18 what they thought a representation of a model was: “Virtually all students in both grades referred to concrete objects (e.g., replicas of airplanes and buildings) as models of concrete objects (real airplanes and real buildings). Very rarely did they refer to models as representations of ideas and/or abstract entities (e.g., mathematical or theoretical models)”

(Grosslight, Jay, Unger & Smith, 1991, p. 804). In the overall conclusion of the report, only 14% of all of the students included the idea that a model can also be abstract. Some of their study included 11 th

grade honors students, however, that would not make up 14% of those who knew a model could be abstract.

Information presented at the annual meeting of the National Association of Research in

Science Teaching in 2000 shows that many students have the misconception that clouds are sponges (Henriques, 2000). She mentions that knowing and recognizing these misconceptions is important because it can “build an entree for instruction” (Henriques 2000).

Perhaps through our own pre-assessment we can expand on the data provided by

Grosslight, Jay, Unger, & Smith (1991) and Henriques (2000). After our pre-assessment, we will have an idea of this particular seventh grade class’ mental model of the water cycle. Once the

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 9 understanding of a model has been reached, it is at that point that discussing that models are both concrete and abstract can be implemented.

Methods

The procedures that we will follow to answer our research question involve an observation of the classroom with a discussion with the teacher about possible science topics to teach (water cycle). Next, we conduct research related to our topic and student’s misconceptions of that topic in an effort to develop a pre-assessment to give to the students in the class. We will then analyze the pre-assessment (by three categories: correct, partial, and un-attempted/incorrect) to see student struggles and misconceptions to develop two lesson plans related to these struggling areas. We will then return to the classroom to conduct a post-assessment to evaluate the success of our teaching and answer our research question.

We visited Ms. McKee’s seventh grade classroom at Dixon Elementary/Middle School during second period. There are 7-9 tables of students with 3-4 students at each table. The students were very talkative and did not seem to be mentally present in the classroom for the majority of the 50 minute period.

Ms. McKee manages her classroom with a loud voice. She says phrases that she often repeats multiple times due to the conversations that the students are having during her lesson.

She seems to allow certain misbehaviors sometimes but then punishes them other times. A student was sent to sit by himself for talking; however, all of the other students talking were not punished. Ms. McKee also uses the method of writing names on the board however; she does not have any consequence for the names being on the board come the end of the period.

The lesson that she taught was not an inquiry lesson. The students copied the definition of a watershed from the smart board and Ms. McKee told the students the functions of a water shed.

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 10

There was no discovering going on and the students just copied down what she presented to them for the entire lesson. This leaves us to believe that conducting an inquiry lesson will be a challenge because these students do not seem to have ever been taught an inquiry lesson. The students will not be used to having to think critically about an idea. They are used to being given the correct answer. Although they sit at tables, it does not seem as though they have worked in groups with their tablemates. Also, their rowdiness in the classroom that is only minimally controlled is going to make the prep for this lesson vital. We will need to have as much done as possible to fit the entire lesson into a 50 minute period given their behavioral issues as well.

The students’ involvement and the students’ prior knowledge may be at a lower level than expected for the seventh grade; however, by knowing this from the observation, we will be able to work with these obstacles.

For our pre-assessment, we will distribute short answer/open-ended questions using a paper and pen method. The pre-assessment will also include a drawing question in which the students will be required to portray their mental model of the water cycle. The following is a brief description of each question. The post-assessment that will be administered is identical to the pre-assessment. Both the pre-assessment and post-assessment tests will be evaluated in the same manner. Each question will be evaluated as: correct, partial (meaning they answered some of the question correctly), or incorrect/incomplete.

Question 1: What are clouds made of?

Idea for question obtained from/developed by: Bar (1989) and Henriques (2000)

Question 2: How do water droplets form on the outside of a cold glass? How did the water get there?

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 11

Looking at the Grade Level Content Expectations (GLCEs) for the seventh grade, we saw that condensation is a term the students need to know (State of Michigan Department of Education,

2007). When looking for misconceptions, we also discovered possible misconceptions in the article by Henriques (2000).

Question 3: Can living things (i.e. plants and animals) activity affect the water cycle in any way?

Give Examples.

This question was inspired by the article by Cardak (2009). In his article, some students did not include plants in their water cycle, even though transpiration is a part of the water cycle. We want to know if students are aware of how living organisms affect the water cycle.

Question 4: a. You spill a cup of water on the sidewalk. When you come back an hour later, the surface is dry. Where did the water go? b. How would this be different if you spilt your cup of water on the grass?

This question was developed using the article by Bar (1989). We are looking to see if the students know that water will evaporate on a non-porous surface, and to see that water can go into the air or be absorbed into the ground.

Question 5: How does air pressure affect the water cycle?

This question was also developed from the article done by Bar (1989). We feel that this question would be very difficult for students to answer, but we want to challenge every student.

Question 6: What is precipitation? List two or three forms of precipitation.

We created this question as a group after reading what is expected of students in the seventh grade GLCEs, seeing how students are expected to know and describe this term (State of

Michigan Department of Education, 2007). We expect that the majority of the class will be successful in the completion of this question.

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 12

Question 7: Antonio and Jennifer are having a discussion about the water cycle. Antonio says that the water that was on Earth when the dinosaurs were here is long gone. Jennifer argues that the water is still on Earth. Which student is correct? Explain.

This general idea of this question was developed by the Plumbing and Mechanical Contractors

Authority of Northern Illinois (2005). Also, after reading the article by Graham, Parkinson, &

Chahine (2000), in which the topic of this question is discussed in an expository manner. This question will require students to understand the water cycle as it relates to the Earth’s conservation of its water.

Question 8: Does the amount of water we have on our planet change or does it remain relatively the same? Explain.

This question was developed after reading the article by Cardack (2009), in which a student misconception is discussed that the amount of water on Earth changes depending upon the weather they are experiencing, for example there would be less water on Earth if they are experiencing a drought.

Question 9: Describe a Scientific Model. Give two examples.

The article by Grosslight, Unger, and Smith (1991) discusses the importance of the use of models to promote science understanding. The idea of models is also the “big idea” of our

Science Capstone course at the University of Michigan – Dearborn, making it vital that we include this question to assess student understanding of scientific models.

Question 10: Do you think a sponge is a good model for a cloud? List two ways that they are the same and two ways that they are different.

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 13

This question was developed using the information about student’s misconceptions regarding clouds as sponges in the article done by Henriques (2002). It also relates to their possible understandings/misunderstandings of scientific models.

Question 11: Draw the water cycle. Include pictures, words, diagrams, etc.

This question was developed by Cardak (2009). The students’ drawings will show their mental model of the water cycle as a whole. We will also use Cardak’s (2009) evaluation system based upon the 5-levels of student drawings. Level one is no drawing, level 2 is a non-representational drawing, level 3 is a drawing with misconceptions, level 4 is a partial drawing, and level 5 is an all-inclusive drawing, the highest level of understanding shown in their drawings.

Results

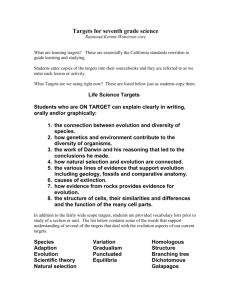

Pre-Assessment Data:

Pre-Assessment Data

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Test Question Number

Correct

Partial

Incorrect/Incomplete

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 14

Pre-Assessment Water Cycle Drawings

5

4

3

2

1

0 2 4 6 8

Number of Responses

10 12 14

Analysis/Data/Conclusions for each Pre-Assessment Question:

Question 1: The first question of our pre-assessment dealt with what clouds are made of. We were surprised to see that 2 students answered correct, 1 partial, and 28 incorrect/incomplete. A possible misconception that several students had was that clouds were made of “water bubbles that hadn’t popped yet.” Based upon these results, we have decided to base one of our lessons on cloud composition. We had not expected students to have this much difficulty with this problem.

Source used for question: Bar (1989) and Henriques (2000)

Question 2: The second question on our pre-assessment had only one student who answered it correctly. Six students gave partially correct answers, and 24 students answered either incorrectly or incomplete. Some students said that the water gets there from the rain; some said that it got there by evaporation, and even some said that the water came through the glass. Only one student said that the water gets there from the air by condensation. We had not predicted that this question would give the students this amount of difficulty, and expected the students to be aware of the condensation process.

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 15

Question based on misconceptions in article by Henriques (2000) and GLCEs (State of Michigan

Department of Education, 2007).

Question 3: The third question on our pre-assessment had seven correct answers, five partial answers, and 19 incorrect/incomplete answers. We were surprised to see that many students believe that living things have no effect on the water cycle. Some of the students were correct, realizing that plants and animals take in water, while others wrote a simple: “no.” Still others believe that there is no effect and the water cycle “happens on its own.” One student wrote: “I forgot” or “don’t know.” This was another question that we did not expect to give them this much trouble.

Source for question: Cardak (2009).

Question 4: The fourth question had 19 correct answers, five partial answers, and seven incomplete/incorrect answers. We were pleased that this amount of the students were able to answer correctly, seeing that water on the pavement would have evaporated, and water spilled into the grass would be absorbed and the majority would not evaporate. Some students believed the “grass drank it all,” but got that the water on the pavement evaporated, earning them a tally in the partial category. There were also some students that left the answer blank, earning an incomplete/incorrect answer.

Source for question: Bar (1989).

Question 5: This question had zero correct answers, three partial answers, and 28 incorrect answers. We had expected this question, pertaining to how air pressure affects the water cycle, to be very difficult for the students, and it certainly was. A misconception that developed out of this question was that air pressure is the same as wind. Another related their answer to water pressure coming out of a hose, and if there is a lot, it will hurt. Many students said something related to:

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 16

“wind blows the air and moves the water cycle.” Many students did not attempt the problem. For those that we credited with a partial response, the answer mentioned pulling evaporated water into the air, or how it lifts the water up and lets the clouds rain. We felt that these students had some sort of idea of how the air pressure can allow for evaporation/precipitation, depending upon if the pressure is high or low.

Source used for question: Bar (1989).

Question 6: This question, asking what precipitation was and what is a couple of examples, produced results that were very surprising to us. Only three students answered correctly, nine students gave partial answers, only answering part of the question correctly, and 19 gave incorrect/incomplete answers. The answers ranged from only listing examples, saying

“evaporation or clouds/water vapor,” to “I forgot,” to even “when water changes from liquid to solid or solid to liquid.” Another student said that it is: “lakes, ocean and stream.” These were very surprising results, as we expected the majority of the class to have an understanding of the topic of precipitation.

Question developed based upon content requirements found in GLCEs for seventh grade: (State of Michigan Department of Education, 2007).

Question 7: This question produced 11 correct answers, 9 partial answers, and 11 incorrect/incomplete answers. The question had students thinking about whether the water from the dinosaur times is still on Earth today. Many students had given the correct response that the water is still here due to the water cycle, while others believed it was gone. One student said:

“when the explosion happened the water was gone just like the dinosaurs.” Others thought that the “dinosaurs had drunk the water, so it can’t be the same.” We had expected a fairly even split in student answers. This also showed a misconception, that the water on Earth is replaced by new

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 17 water. A partial response would be one where the students had answered correctly, but their reasoning was not related, such as: “I think the water is still here. I say that because we drink the same water.”

This general idea of this question was developed by the Plumbing and Mechanical Contractors

Authority of Northern Illinois (2005). Also, after reading the article by Graham, Parkinson, &

Chahine (2000), in which the topic of this question is discussed in an expository manner.

Question 8: This question is related to the previous question. We hoped for the students to see that the water cycles the water, and maintains the amount of water on our planet to remain relatively the same. Eight students answered correctly, seven gave partial answers, and 16 gave incorrect/incomplete answers. An example of an incorrect response given is: “It changes because if it rains in one ocean than we have more water.” This shows another possible misconception students may have, that the amount of water changes. An example of a partial response would be: “I think it remains the same because it is a lot of water to be changing.” One part of the answer is correct, but the reasoning is incoherent. We had expected this problem to be challenging for students, but with an understanding of the water cycle, they should have been able to answer correctly.

This question was developed based on misconceptions in Cardak (2009).

Question 9: This question, asking students to describe a scientific model, had 2 correct answers,

6 partially correct answers, and 23 incorrect/incomplete answers. Some students confused a scientific model with the scientific method, while some had an idea that a model represents something else by their answer: “A scientific model is a remake of a watershed or a volcano.”

Many students left the problem blank. During the test, I was called over for help by the students the most on this question. Many thought that it was an experiment of some sort, and I

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 18 encouraged them to write down whatever they feel the answer could be. Some wrote definitions of condensation and evaporation, but I did not get an impression that many students knew what a scientific model was.

Source used for question: Grosslight, Unger, & Smith (1991), which discusses the importance of models in science.

Question 10: This question had 5 correct answers, 17 partial answers, and 9 incorrect answers.

By having the students list two ways a sponge is the same as a cloud and two ways they are different, this produced a lot of partial answers, as they were only able to answer some of the question correctly. For example, a student response was: “Yes, cause it suck the water up, and it let the water go.” An incorrect answer would be: “no because a sponge will only get out only a little bit of water, and clouds get all of it out.” I found it interesting that some students who had not been able to answer the previous question about scientific models were able to answer this question, indicating that after an example was given, they were able to gain some idea of what a scientific model would be.

Source used for idea of student misconception of clouds as sponges: Henriques (2002).

Question 11: This question had students drawing the water cycle. For this question, we evaluated students’ drawings according to different levels, as described in the article by Cardak

(2009). Five students had level 1 drawings, in which they had not attempted to draw or left the space blank, with no representations. Twelve students had level 2 drawings, in which they had attempted the problem, but the drawing was non-representational. Seven students had level 3 drawings with misconceptions. Seven students had level four drawings, which were partial but lacked misconceptions, and zero students had level 5 drawings which would have included detailed, correct drawings.

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 19

Source used for evaluating student drawings and idea for question: Cardak (2009).

Pre-assessment results linked to lessons 1 and 2:

The pre-assessment results show that only 18% of the pre-assessment answers were complete correct answers. Therefore 82% of the pre-assessment responses are evidence that the students lack the foundational knowledge of the water cycle, or at least are unable to apply it to a formal assessment. For this reason we need to provide these students more exposure to activities which allow them to see the water cycle in action.

Based on the analysis of the pre-assessment data, we realized that the students did not have the vocabulary or understand the vocabulary involving the water cycle. Twenty-eight out of thirty-one students did not know how a cloud was formed and what a cloud is made of. Also,

70% of the students did not understand that the water cycle is a natural phenomenon in which the earth’s water is conserved. That is, water does not “run out” or disappear. Instead, we explain how water changes its state and travels in the atmosphere. Another topic we hope to cover in our lessons is how living things affect the water cycle. Nearly every student was capable of stating that all animals and plants need water to survive. However some students seem to think that if there were enough plants on earth that the water on earth would dry up. We hope we can show students through our lessons that this is not the case.

We plan to teach a lesson that shows students how water vapor condenses onto particles in the air to form water droplets. Clouds are formed from water droplets. When multiple water droplets combine and get heavy, gravity pulls them toward the earth causing precipitation, the main idea for our second lesson. To show that living things are involved in the water cycle, we would like to show students a terrarium. If students can see that a plant can survive in a jar without constant watering, perhaps they will connect how water from plants goes back into the

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 20 air as water vapor through transpiration. This can help expel the misconception that the earth can dry up if there are too many plants.

In our second lesson, we will investigate precipitation and the other main processes of the water cycle with the students. They will investigate evaporation, condensation, and precipitation in an effort to explain the water cycle. From our pre-assessment, only 3 out of 31 students gave a complete, correct answer when asked what precipitation was and to give examples.

Summary of lessons 1 and 2:

For lesson one, the main topic of the lesson was cloud formation. This also allowed us to touch on evaporation and condensation. We asked the students for their initial thoughts regarding how clouds were formed. We then gave them materials so that they could test these predictions.

These materials included plastic cups, sandwich bags full of ice, warm water, and matches. After their exploration, the teachers walked to each group and properly conducted the experiment, blowing the match out, dropping it into the water, and then having the students cover the cup with the ice. We wanted students to understand how the water vapor condenses to make water droplets, which adhere to the smoke particles in the air to make a cloud. The idea for this “cloud in a cup” activity came from Professor Hartshorn, a science professor at the University of

Michigan - Dearborn.

Next, a chart was created on the board to match each model to its target in reality. For example, the cup represents the atmosphere, the ice being the cold atmosphere above and the warm water representing the surface water of the Earth. The smoke from the match represents the condensation nuclei that the water vapor condenses on. To extend the lesson, we investigated living things and their effect on the water cycle. We brought in a terrarium with soil, plants, and a bug inside. We asked the students what else would be needed to expand our model of the

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 21 atmosphere, hinting at living things. We assessed the students through the completion of their worksheet that guided them throughout the lesson and informally through class discussions.

In lesson two, we incorporated the third, major process in the water cycle: precipitation.

To engage the students we reviewed what we had learned in the first lesson and discussed how that model showed evaporation and condensation. We asked them what process is left in the water cycle, the process of precipitation. For exploration, we wanted the students to explore how to make rain inside of a jar. Small groups of students were given a mason jar with previouslymade dents in the lid, a bag of ice, and warm water to put into their jars to explore. A heat lamp and hot plate were used by the teachers to set up a demonstration. As groups realized that a source of heat was needed to initiate the evaporation process which would eventually lead to precipitation, they came to the front of the room to observe this demonstration.

To address and connect the major ideas of the water cycle, we led a discussion about how evaporation, condensation, and precipitation all occurred at specific points within our jar model.

To extend the lesson we asked the students what would be necessary to make it snow in the jar.

Finally, to evaluate the students, we had them draw the water cycle on large sheets of paper as groups or individually if they preferred. This was a good review for the post-assessment as well.

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 22

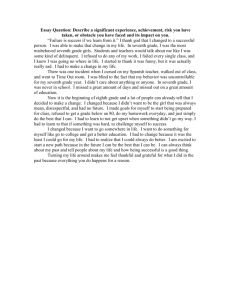

Post-Assessment Data:

Post-Assessment Data

15

10

5

0

30

25

20

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

Test Question Number

Correct

Partial

Incorrect/Incomplete

Post-Assessment Water Cycle Drawings

5

4

3

2

1

0 2 4 6

Number of Responses

8 10 12

Analysis/Data/Conclusions for each Post-Assessment Question:

The following is a summary of the responses from our post assessment. However it should be noted that 31 students were present for the pre-assessment whereas only 27 students were present for the post-assessment, including a student who went home due to illness. Also, not all

27 students taking the post-assessment were present while we taught the two lessons. One

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 23 student did not want to participate during the test. All questions were left unanswered by this individual aside from the water cycle drawing after one-on-one prompting from the pre-service teacher conducting action research for 20 minutes. Only 12 out of the 27 students taking the post-assessment were present during the pre-assessment and both inquiry lessons.

Question 1: What are clouds made of?

16 out of 27 students understood that clouds are made of water droplets due to the two lessons as well as the review prior to the post-test. Despite multiple reminders and explanations that clouds are not made of water vapor, 5 students still wrote that clouds are made of water vapor (gas). 3 out of those 5 students were present for all lessons. Therefore we can conclude that two lessons were not enough to dispel their misconception.

Source used for question: Bar (1989) and Henriques (2000)

Question 2: How to water droplets form on the outside of a cold glass? How did the water get there?

10 out of the 12 students present for all lessons got this question wrong. Perhaps this is because we did not explicitly state that condensation of water droplets occurs on the outside of a cold glass. They weren’t able to apply condensation, in the form of our cloud experiment, to another everyday occurrence of condensation. 4 students total got this question correct, one of whom was present for both lessons. Some incorrect responses are as follows: “perspiration”, “by rain, sleet, or snow”, “from heat”, “by evaporation”. Four students did not respond to this question.

Question based on misconceptions in article by Henriques (2000) and GLCEs (State of Michigan

Department of Education, 2007).

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 24

Question 3: Can living things’ (i.e. plants and animals) activity affect the water cycle in any way? Give examples.

11 out of 27 students received full credit for this question. Seven out of those eleven students were present for both lessons. Some incorrect responses: “Animals are not associated with the water that we drink.” Three students did not answer this question while another student wrote “I don’t know.” One student wrote “no” with no further explanation. Other students that replied

“no” had invalid but often complete explanations such as “animals don’t live in our drinking water” or “plants don’t affect the water cycle because they are already a part of it.” The last response suggests that the students may not have understood the question. We often addressed transpiration in our lessons and even supplied the class with a terrarium for three weeks that included a rose and beetle.

Source for question: Cardak (2009).

Question 4: a. You spill a cup of water on the sidewalk. When you come back an hour later, the surface is dry. Where did the water go? b. How would this be different if you spilt your cup of water on the grass?

There were 16 students out of the 27 students who received full credit for this question, 8 of whom were present for all lessons. Only one response was incorrect, one student did not respond at all. Everyone else received partial credit.

Source for question: Bar (1989).

Question 5: How does air pressure affect the water cycle?

This question was included in our assessments to challenge all learners. Our lessons did not address this topic. However, 5 students received partial credit. Their answers suggested that air

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 25 pressure could affect humidity, precipitation and evaporation. These may have been lucky guesses. The rest of the students got this this wrong or did not attempt as we expected.

Source used for question: Bar (1989).

Question 6: What is precipitation? List two or three forms of precipitation.

5 students received full credit, 14 students received partial credit. The students that received partial credit were able to give examples of precipitation but did not define the term. Examples of incorrect answers: “It forms water droplets on things like glass and windows” this answer suggests confusion between precipitation and condensation, “It is when chemicals get in the air” and “clouds.”

Question developed based upon content requirements found in GLCEs for seventh grade: (State of Michigan Department of Education, 2007).

Question 7: Antonio and Jennifer are having a discussion about the water cycle. Antonio says that the water that was on Earth when the dinosaurs were here is long gone. Jennifer argues that the water is still on Earth. Which student is correct? Explain.

All students present for both lessons got this question correct or partially correct. 19 out of the 27 students taking the post-assessment received full credit. 3 students had incorrect responses and one of them was unanswered.

“Jennifer is because the water that was her with the dinosaurs froze into glaciers and turn into mountains.”

“Antonio is right because the water is old and gone. We wouldn’t have the same water then that we drink now.”

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 26

This general idea of this question was developed by the Plumbing and Mechanical Contractors

Authority of Northern Illinois (2005). Also, after reading the article by Graham, Parkinson, &

Chahine (2000), in which the topic of this question is discussed in an expository manner.

Question 8: Does the amount of water we have on our planet change or does it remain relatively the same? Explain.

14 students received full credit, 12 received no credit, and one student received partial credit.

Some examples of incorrect responses: “we drink it so there is less”, “changes by pollutants” and “It goes somewhere” (with no further explanation). Other answers were illegible or we were unable to comprehend their answers. Four students left question 8 blank.

This question was developed based on misconceptions in Cardak (2009).

Question 9: Describe a scientific model. Give two examples.

Only one student received full credit. Sixteen students received partial credit and this was due to only giving examples (the models from the lessons we taught) but did not describe a scientific model or state what they are used for. Eight students left this question blank, six others received no credit for their responses. We were surprised by the low number of correct responses. We explicitly defined a scientific model more than once to all the students directly before the test as well as during the lessons. Incorrect responses often included the processes of the water cycle such as evaporation, condensation and precipitation.

Source used for question: Grosslight, Unger, & Smith (1991), which discusses the importance of models in science.

Question 10: Do you think a sponge is a good model for a cloud? List two ways that they are the same and two ways that they are different.

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 27

The accuracy of answering this question was based solely on the students’ justifications. If two students disagreed as to whether a sponge is a good model for a cloud, both students had the opportunity of receiving full credit, provided they listed two similar and two dissimilar traits and justified their position. Most loss of full credit was due to not providing examples or justifications. Anyone who attempted this question received some credit. The four students who did not receive credit for this question did not attempt the question.

Source used for idea of student misconception of clouds as sponges: Henriques (2002).

Question 11: D raw the water cycle. Include pictures, words, diagrams, etc.

We adopted Cardak’s (2009) grading scale for the drawings. However, we adapted the full-credit score criteria with consideration of our lessons by considering full credit to be inclusive of all of the topics that we explicitly addressed: ground water, evaporation, transpiration, condensation and precipitation and then sun.

Source used for evaluating student drawings and idea for question: Cardak (2009).

Here is an example of each level of student drawings, from level 1 to level 5:

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 28

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 29

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 30

Conclusion

Our research question for our action research project was: What is the impact of our teaching 7 th

grade students about the water cycle and models? We found that our teaching had an impact and is the first step in increasing the student’s knowledge of the water cycle. Our two lessons were not enough to address all misconceptions and form a mental model in every student’s mind, but we have seen improvement in their understanding. The student’s experienced more success after our lessons on test questions whose topics were directly addressed in our two lessons, such as cloud formation, living things’ effect on the water cycle, conservation of water, and for the questions regarding scientific models, there was an increase in the amount of partial responses and a decrease in the amount of incorrect/incomplete responses.

In question 11 of the pre-assessment, not one student recorded a level 5 drawing. Twelve students gave a level 2 drawing, and 5 students got a level 1 drawing. For the post assessment, 11 students gave a level 3 drawing and 4 students gave a level 5 drawing. The student’s understanding of the water cycle increased, as demonstrated by their drawings. These water cycle drawings are good indicators of their understanding of the water cycle and its major processes. The twelve students who were in class during both of our lessons increased at least one score. In the pre-assessment, only one question had more correct responses than incorrect or partial responses. In the post-assessment, five questions had more correct responses than incorrect or partial responses. This shows an improvement, as at first the students were only getting one question on the test correct, whereas on the post-assessment, the students were getting roughly half of the test questions correct.

In question 9 of the pre-assessment, addressing scientific models, 74% of the responses were incorrect and 19% were partially correct. In the post assessment, 51% of the students gave

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 31 incorrect answers and 44% gave partial responses. This demonstrates an increase in student understanding, but also indicates that there is still room for improvement.

In preparation for our project, we conducted initial research regarding the topics of our research project. This research included the topics of possible misconceptions in science in general as well as misconceptions related specifically to the water cycle. Another research article discusses using models in middle school and high school and related misconceptions. Bar (1989) discussed misconceptions that young children in middle class Jerusalem have related to cloud formation involving that clouds are made of smoke (Bar, 1989, p. 484). Our research showed that lower socio-economic status children in Detroit also have this misconception. Cardak (2009) interviewed university students in Turkey through their drawings of the water cycle. We did the same for seventh grade students in Detroit, adding onto Cardak’s research by expanding the age group evaluated.

Another article asked students ages 11 to 18 what they thought a scientific model was

(Grosslight, Jay, Unger, and Smith, 1991). We did the same in our pre and post assessments in questions 9 and 10 and our students’ age group also fits into this range. In Henriques’ (2002) article, she discusses misconceptions that students of varying grade levels have regarding weather, and more specifically, cloud formation. We used this article to inform our preassessment planning and our lesson planning. Our action research confirms the misconceptions that Henriques (2002) states in the article. These include that clouds are made of smoke, dust, and can expand to include the misconception that clouds are made of water bubbles that have not popped yet. Another student said that clouds are made of gas that can produce rain.

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 32

Reflection Notes

Steven Pascoe’s Reflection:

From our teaching, I feel that the students have learned several concepts or have a more detailed mental model of the topic of the water cycle. To begin with, our first lesson focused on how clouds were formed and what they were made of. As a result of this lesson, the amount of students who got this question correct on the post-assessment increased from 2 to 16. We also discussed how living things affect the water cycle, leading to four more students providing correct answers on this question. In our second lesson we taught the students about how precipitation forms and what precipitation is. Also included in this lesson were demonstrations and discussions of the other two major processes of the water cycle in addition to precipitation, evaporation and condensation. As shown on their post-assessment, students were able to draw the water cycle with greater success than on their pre-assessment. On the pre-assessment, no students had level 5 drawings and seven students had level 3 drawings. These numbers increased to 4 students with a level 5 drawing and 11 students with a level 3 drawing. We saw higher-level drawings from the students in general, indicating a better understanding of the water cycle and its various components thanks to our teaching.

In addition to student learning, I have also gained valuable insights and new knowledge throughout this project. I learned how to conduct an action research project with a team. We developed a starting point through observing a classroom, speaking with the teacher, and developing a pre-assessment. Using this pre-assessment, we discovered student misconceptions and/or lack of knowledge and created two lessons to teach to the students. We then returned to assess their learning and the effectiveness of our lessons through a post-assessment. This process was new to me and I have never conducted an action research project prior to this experience.

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 33

Through the pre-assessment, I learned of students’ lack of knowledge and misconceptions, many of which were very surprising to me. I was surprised that many of the seventh grade students did not know what precipitation was or that clouds were made of “little water bubbles that haven’t popped yet.” The students also were largely unaware of the major processes of the water cycle and struggled to draw the water cycle. Using this information, we developed lessons in response to specific student needs. In the post-assessment, I learned how successful we were as a team of addressing these misconceptions and lack of knowledge. I witnessed how effective inquiry lessons can be for students and also learned how we had not reached every student as indicated by partial, incorrect, or incomplete answers to questions whose topics we had addressed.

For future teaching, I learned of the importance of first pre-assessing students to discover what some of them know and do not know. We then use this information to inform our teaching.

By directly using student’s prior knowledge and thinking to inform our lessons, we ensured that we were covering relevant material for our students. This is something that I will take with me and think about as a future teacher. Also through this project, I learned that it may take more than one or two lessons on a particular topic to change student thinking. Even after our lessons that directly addressed certain topics the students struggled with, many students still indicated that they need further instruction. Continued lessons and/or review on the material would better help to address the needs of every student. In fact, this is addressed in the spiral approach of action research. In this approach, we would continue our researching project by repeating our steps until the misconceptions and lack of knowledge are addressed. Unfortunately, we did not have time to do this in our collegiate course.

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 34

The science content and school context affected our action research lessons in many ways.

Our lessons were designed in direct response to the science content and the school/student contexts. We started the project by observing the classroom to learn of their science experiences and how their normal lessons were taught. We learned that science through the inquiry process was not the norm for the school. We also gathered a science topic to teach the students from our cooperating teacher. Using this topic, we created a pre-assessment to give to the students. This assessment was used to draw out misconceptions and lack of knowledge within the students. In analyzing this data, my team and I created a list of possible topics and misconceptions that needed to be addressed, thus informing our two lessons. We learned about their misconceptions and lack of knowledge regarding: cloud composition and formation, living things’ effect on the water cycle, water conservation through the water cycle, and the three major processes of the water cycle, evaporation, condensation, and precipitation. These topics were the subjects of our two lessons, signifying that our lessons were created in direct response to the science content and the school context.

When we were planning our lessons, we considered several important factors. First of all, we took into consideration the results of the pre-assessment. This gave us the topics for our lessons as the assessment indicated where the students were lacking knowledge or where they had misconceptions related to the water cycle. We also took into consideration the fact that these students were not used to inquiry science lessons. This meant that they would need more help and guidance through the lessons. In each lesson, we provided the students with a worksheet that would guide the students through the lessons. We also walked around the room and worked with each group. We planned for safety issues as well, as our lessons dealt with the use of heating materials, glass, and matches. Therefore, the teachers present were in charge of these materials.

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 35

In our observations, we also looked for the kinds of materials that would be available to us in the classroom for our lessons. This way we knew what we would have to plan to bring in ourselves on the days that we actually taught the lessons.

The scientific theme of the Capstone Course, models, was incorporated into our lessons and played an integral role throughout out action research project. We began to address this theme in our pre-assessment, when we asked the students if they knew what a scientific model was and if they could give examples (Grosslight, Unger, & Smith, 1991). We also asked them to compare the model of a sponge to a cloud in reality (Henriques, 2002). These questions provided insight into students’ previous knowledge about models. Next, we incorporated models into our lessons. The first lesson involved a cloud in a cup model. The cup represented the atmosphere, with the ice being the cold, upper atmosphere, and the warm water being the Earth’s surface.

During this lesson, we also discussed with the students what each part of the model represented, drawing the connection between the model and the target. In our second lesson, we used a similar model, to show how precipitation occurs, along with evaporation and condensation. The students worked with this model, and even created another model when they worked to draw the water cycle. Models were used throughout our lessons and throughout the topics that we were teaching, demonstrating why it is that they are considered a scientific, unifying theme.

In the future, I will need to take into account many different aspects when considering what teaching method I will use for a particular science concept and a particular school setting.

In regards to the Pedagogical Content Knowledge (PCK), I will need to account for the context, content, and pedagogy. I will think about the classroom context, specifically the students that I have, their past experiences, and their prior knowledge. I will think about the content that I need to teach, and how that content could best be taught to my students. I will also use my pedagogy,

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 36 or what I know about teaching, to best decide on what method to use to teach a certain concept.

This pedagogy may come in the form of a 5 E Inquiry lesson, as was the case in this action research project.

To be effective, teachers must have both content and pedagogical knowledge. They must not only know the content material, but they must also know how to effectively teach this material to their students. To start, the teacher needs to know and understand what he/she is teaching to their students. This way they can properly present the material and know how to assist students when they are in need of help. In addition, knowing the most effective way to communicate to students is vital to teaching subject matter. The teacher must also know the students that they have in their classroom. This classroom context is important to effectively teach the desired material. The classroom dynamics such as student experiences, the school district, cultures, and available resources, all play a part in knowing and being prepared to effectively teach. The classroom teacher needs to have several kinds of knowledge to be effective.

Lucy Zahor’s Reflection:

The seventh grade students at Dixon Elementary in Detroit, Michigan showed some improvement on their knowledge of the water cycle from my teaching. The students have shown improvement on concepts such as the makeup of clouds, the conservation of water, and the overall pattern of the water cycle. Their drawings of the water cycle also included concepts not addressed in the pre or post assessment but that were touched on during lessons such as the process of transpiration. There was no improvement to the concepts that we did not address, such as the effect of air pressure on the water cycle, as expected.

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 37

We found there to be consistency throughout the improvement of the students that the 12 students that had been present throughout the pretest and two inquiry lessons, had the most accurate answers of all of the students. I discovered, through the analysis of this data that my teaching had a positive impact on the knowledge of the water cycle to these seventh grade students.

Throughout this action research project, I learned much about my own teaching.

Classroom management skills became an important skill, especially when all 31 students were in the classroom. Using tactics such as waiting on them to finish their discussion didn’t work for these students. By the second session, I realized that I needed to reasonably discuss the idea of respect with them. I came into their room and respected them while they were talking and asked them if they thought it was reasonable for them to not talk while I was talking. They agreed and for most of the time following, time, they were cooperative.

During this action research project, I also discovered the importance of the engage portion of an inquiry lesson. If we did not capture their interest initially, we would not be able to have them learn throughout the rest of the lesson. These students, however, had very little experience with inquiry formatted lessons and were engaged to be using more than a pen and paper to learn science concepts.

This project was very helpful for my future teaching because of the format. I plan to adapt this idea of using a pre-test to find out what the students already know and then to teach to their misconceptions and lack of knowledge. It will allow me to see what they already understand completely and what parts of a particular concept need to be readdressed.

It was also helpful because, with the lessons, I am getting a better understanding of the time constraint that the set up has. Science lessons in particular require much more set up than

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 38 other subjects such as Language Arts. The preparation a materials consumes much of the given time and doing this ahead of time will definitely prove to be more beneficial in the future.

After the pretest, we discovered that the students are far below grade level when looking at their knowledge of the water cycle. The students didn’t understand specific terms such as precipitation and evaporation. They also were unfamiliar with the format of an inquiry lesson and therefore, not used to the routine in which an inquiry lesson works.

One of the misconceptions that the students generally had was that clouds are made of tiny water bubbles that pop when they collide together and it rains. I asked multiple students why they thought this but could never get a clear answer from anyone. Due to this common misconception, we wrote our first lesson with the concentration on cloud formation. This lesson was proven, in the post test, to have helped clear up this misconception and we did not receive any similar answers to the bubbles waiting to pop on the post test.

Misconceptions were a major consideration when planning our lessons. We also considered factors such as time, equipment, safety and the level of difficulty. We could not plan lessons to address seventh grade content when the students didn’t understand basic scientific principles such as the conservation of water. We had many concepts that we needed them to understand in order to understand cloud formation. This was challenging however, we managed to be able to use our model of a cloud in a jar to demonstrate evaporation, condensation and even get them to think of how precipitation might occur in the jar over time.

For our second lesson, we considered that we didn’t want them to have forgotten the knowledge from the first lesson so we again used a jar of water in order to show precipitation.

This is important because the second lesson unified the concepts from the first one as well. We were attempting to give them a knowledge base and build on what they already knew.

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 39

To show the students the way that the water cycle works in nature, we obviously couldn’t use the atmosphere but we could use a model to show the students that we can bring science into their classroom. When forming the cloud in the jar, we explained to them how each part of the model represented its target in nature. The students were able to think of this more concretely with models that they could see, touch and manipulate than the abstract format they are used to of reading our of a textbook.

We also made a classroom model of a terrarium with a small plant, a beetle, soil and water. This was to help the show the idea that living things affect the water cycle and that water is constantly recycled within our planet. The students were able to look at this as they answered their questions of how living things can affect the water cycle. I feel that this model helped them to solidify concepts of the water cycle.

In future work, if working with students who are brand new to the inquiry format of a science lesson, I would make the possible options of variables more limited. The students weren’t able to construct a model at first without given a list of optional materials because the idea was broader than any other science activity they had likely ever done. I would definitely use this format again; giving them a list of optional variables instead of allowing them to use anything they can think of. The lessons were still inquiry and given the situation again, I would again make them inquiry; however, they are much more guided format of inquiry. One in which the students can focus more on the science concept instead of the inquiry concept.

I believe that a teacher must have both content and context knowledge. I had the knowledge of the content for the concept of the water cycle but learning the context of the students was something that cannot be fully understood without being in the classroom, working with the students. I believe that to be effective as a teacher you need to understand what it is that

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 40 the students already know, what ways they are familiar with learning, and what misconceptions they have. I believe that this action research project overall helped me to understand a very effective way to teach to what the children need to learn.

Elaine Bechard’s Reflection:

Looking at the pre-assessment, the students’ incorrect responses far outweighed the number of correct answers for each question only 1 out of 10 questions had a higher number of correct responses than partial or correct responses. For the post assessment, 5 out of 10 questions had a higher number of correct responses than partial or incorrect responses. Also, on the drawings, there were no level 5 drawings on the pre-assessment and the highest frequency of scores was at a level 2. However for the post-assessment most students got a level 3 and four students achieved a level 5 score for the drawing for the post-assessment.

The action research project not only taught me the steps to an action research project, but it also taught me that inquiry science and models based science teaching can be use for all classrooms. The process of the action research project also taught me a valuable way to both assess my students and my lessons. The project had my group and I first observe the students, create a form of assessment. We have the students the pre-assessment, used that lesson to create two lessons and then gave the students the same assessment after the lessons. This shows us how much the students have learned as well as how effective the lessons were in teaching particular content. I had my doubts as to whether teachers would have time to teach inquiry lessons to students that were already behind. I found that our lessons did help many students. As a future teacher I will try to incorporate as many inquiry lessons and models as I can while also being a reflective teacher and evaluating myself and my lessons.

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 41

During our first observation of the seventh graders at the Detroit school, the students were talking about the water cycle and were starting a lesson on watersheds. The students were answering questions on the board related to the water cycle. The two questions and their responses caught my attention most. “Where is all the water on the Earth located?” and “How much of the Earth’s water is located in the oceans?” I found the first question to be odd and also misguiding. The students answered the first question by stating that all the water is in the oceans.

The teacher said this answer was correct. Then they said that about 97% of the Earth’s water is located in the oceans. Right away I knew my group and I would encounter many misconceptions on the water cycle and that these students were not in the habit of questioning information they were taught. Either the ocean contains 100% of the Earth’s water or only 97%. Both answers could not be correct but no student raised this question during the class period. So, having the students think critically and form their own explanations would most likely be a challenge for them. So even though the teacher told us that they had just finished talking about the water cycle, my group and I thought that there would be many gaps in their understanding of the water cycle and we wanted to see what they were and if we could address any of them. The lack of knowledge the students had and the topic they were about to start learning gave my group and I specific science content to teach in our action research lessons.

The most important factors my group and I considered while planning our lessons, was deciding which content was most important to teach. Our pre-assessment showed that the students lacked significant knowledge on the water cycle both in terms of science vocabulary as well as the processes of the water cycle. The students could not give a definition of precipitation, nor could they describe ways in which humans or plants could be involved in the water cycle.

They also did not know what a scientific model was. We decided to focus on the questions most

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 42 students got wrong. We wanted to incorporate models into our lessons that also addressed the most questions on our assessment. We wanted our lessons to help students create a mental model of evaporation, transpiration, condensation, and precipitation and where these processes can be seen. We wanted students to be able to see how the sun, ground water, and water vapor are involved in the water cycle as well.

My group and I incorporated the scientific theme of the Capstone Course, models, by focusing on a way to physically represent processes in the water cycle. We wanted students to construct a model of condensation and precipitation. In our own science classes at the University of Michigan-Dearborn, we have experienced many inquiry lessons. A particular lesson was very useful to us in creating our own lessons for the seventh grade students. During the Explore phase of our first lesson, we had students create a model for a cloud using a clear plastic cup, warm water, a match, and a bag of ice. The students tried to create a cloud in their jar but were unsuccessful. My group and I then had them create the model that we proposed, putting warm water in the cup, blowing out a match and then placing the bag of ice over the mouth of the cup.

During the explain phase we had the students compare their procedure to our procedure. We had a class discussion on what each part of our model represents in the formation of a real cloud and how our model is different from the actual formation of a cloud. We also used another model in our Extend phase of the inquiry lesson. We showed students a terrarium in a jar and asked the students what they think each part of the terrarium represented in the real world.

In the second lesson, we also used a model in the Explore, Explain, and Extend phases. We also engaged the students into the lesson by asking them to remember the model used in the previous lesson and how the model related to the real world. So while the students did not have that model in front of them, they were able to demonstrate that a mental model was forming of

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 43 the processes of evaporation and condensation. Our second lesson had the students try to produce rain. The idea was to get students to apply the cloud model to rain. The goal was to have students construct a model of precipitation and how it connects to evaporation and condensation.

After the students tried to create a model, my group and I showed the students the way to construct the model and to take a look at one we had prepared. During the Explain and Extend phase we asked the students what each part of the model represents and how it is still different from the real target. We then asked the students to think about snow and how we would need to change our model to create snow.

After our first visit, the observation, I thought the students would have trouble participating in an inquiry lesson since they did not appear to have any experience learning science in this manner. However, I found that the students were actively engaged and were eager to participate in an exciting lesson. This convinced me that inquiry science and models based teaching can work with all students. The students were already placed into groups, however, if they were not, that would be one small obstacle that could be overcome easily. I can easily apply what I learned from the action research project to how I will teach in the future. The first step is to see what the students already know, and what misconceptions they may have. Then, I can create inquiry lessons that incorporate models to teach to the specific areas in which my students lack knowledge.

To be an effective teacher, a teacher must first be knowledgeable about the actual content.

A teacher should understand the concept he or she is trying to teach as well as how it fits into the bigger picture. Furthermore, a teacher, especially in science, must address his or her own misconceptions. This is necessary in order to anticipate and understand the different kinds of misconceptions the students will have. A teacher will not want to pass down his or her own

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 44 world. misconceptions to the students. Rather a teacher needs to know the different ways to address different misconceptions. For example, a vernacular misconception in which everyday usage of the word does not match the scientific meaning of the word, a teacher just needs to be explicit when comparing the usage of the particular word in science. However, a preconceived notion is not so easily clarified. In order to change a student’s mental model of the world around them that he or she has created based on his or her own observations, a teacher must supply that student with many opportunities to replace the misconception with new knowledge. A teacher must then also be knowledgeable on the best means to “un-teach” the misconceptions and replace them with correct models. A teacher should have an ideal mental model that the students should have and an idea of ways to get the students to construct that model in a meaningful way. Inquiry science teaching mixed with models based science teaching allows students to construct their own knowledge as well as learn how the activities or models are different and similar to the real

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 45

References

Bar, V. (1989). Children’s views about the water cycle. Science Education , 73 (4), 481-500.

Cardak, O. (2009). Science students’ misconceptions of the water cycle according to their drawings. Journal of Applied Sciences , 9 (5), 865-873.

Graham, S., Parkinson, C., & Chahine, M. (2000). The water cycle. Retrieved from http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Features/Water/water_cycle_2000.pdf

Grosslight, L., Unger, C., Jay, E. & Smith, C. L. (1991). Understanding models and their use in science: Conceptions of middle and high school students and experts . Journal of

Research in Science Teaching, 28 (9), 799-822. Retrieved from http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/tea.3660280907/abstract

Henriques, L. (2002). Children’s ideas about weather: A review of the literature.

School Science and Mathematics , 102 , 202-215.

Henriques, L. (2000) Children’s Misconception Weather: A review of literature. Social Science and Mathematics, 5 (102), 202-215. Retrieved from http://www.csulb.edu/~lhenriqu/NARST2000.htm

Plumbing and Mechanical Contractors Authority of Northern Illinois. (2005). Get to know H2O:

Test your knowledge. Retrieved from http://www.get2knowh2o.org/student/cycletest.html

State of Michigan Department of Education. (2007). Science grade level content expectations

(v.1.09). Retrieved from http://www.michigan.gov/documents/mde/Complete_Science_GLCE_12-12-

07_218314_7.pdf

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 46

Thacker, D. (n.d.). How does snow form? Retrieved from http://www.ehow.com/howdoes_4563981_snow-form.html

THE WATER CYCLE: IMPACT OF TEACHING SEVENTH GRADERS 47

Tentative Time Schedule:

Classroom Observation : 10/1/12

All group members present and involved.

Pre-Assessment : 10/15/12

All group members present and involved.

Teaching Lesson 1 : 11/12/12

All group members present and involved.