to Dr. Paul Spector's PowerPoint slides.

advertisement

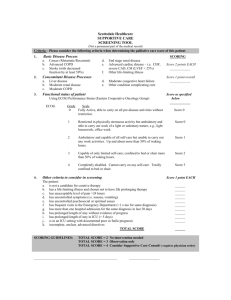

Induction, Deduction Abduction: Three Legitimate Approaches to Organizational Research Paul E. Spector University of South Florida November 6, 2015 Roadmap • Nature of inference – Exploratory, Confirmatory, Explanatory • • • • History Current state of research approaches Winds of change Guide to inductive/abductive methods – – – – Data mining/data science Inductive methods Writing inductive papers Evaluating inductive papers • The way forward Three Types of Inference • Deduction – Reasoning from true premises – Confirmatory research • Theory/hypothesis testing • Induction – Generalizing from observations – Exploratory research • Abduction – Inference to best explanation – Explanatory research Deduction • Reasoning from true premises 1. All students have laptops 2. Mary is a student 3. Therefore: Mary has a laptop • If 1 and 2 are true, 3 must follow • 2 and 3 can be true even though 1 is not Deduction: Theory Testing • Confirmatory theory testing 1. If theory is true (X leads to Y) 2. X relates to Y • If 1 is true, 2 follows • Finding 2 is support (confirms) 1 • 2 can be true even if 1 is false Deduction: Model Testing 1. X1 M Y X2 2. Data will fit predetermined pattern • If 1 is true, 2 follows • 2 can be true even if 1 is false – Model equivalence problem Deductive Inference • Conclusion rests on truth of premises • If premises are true, the conclusion is true • What if premises are false? – Mary has a laptop even though not all students do – Mary lied about being a student • Confirmation suggestive not conclusive Deduction, Confirmation, Disconfirmation • Deductive test of theory – Collect data to confirm – Uncertainty that additional cases disconfirm • Theory: All swans are white – Confirmation requires checking every swan – Disconfirmation requires finding only one black swan Inductive Inference • Generalizing from observed cases – All students in my class have laptops – Therefore all students have laptops • Assumption that future cases same as observed • Assumes uniformity of nature • Future cases not necessarily the same – Boundary conditions – Population differences – Type 1 errors Inductive Study • Collect data on a phenomenon • Generalize conclusions • Observe pattern of sample relationships • Conclude pattern exists in population Features of Inductive Research • • • • • Exploratory Not explanatory No hypothesis/theory to test Has purpose/question to address Need to define scope of generalization – What is the population? – Boundary conditions • Discovery rather than confirmation • Allows serendipity Abduction • Inference to the best explanation 1. We observe X 2. We reason that the best explanation is A 3. We conclude that A is therefore true • • • • Beyond inductive generalization Attributions Theory based on observation What is criterion for “best”? Criterion for Best Explanation • Testable • Parsimony • Explains most variance – Most accurate prediction • Explains most phenomena – Relates to the most variables • Makes most sense: Subjective Integrated Approach • Deduction – Theory test • Induction – Exploratory discovery • Abduction – Theoretical explanation for observations • Ideal order – Induction Abduction Deduction History of Inference in Organizational and Related Sciences Exploratory Phase • • • • • Prior to 1980s Behaviorism Emulate physical science Focus on observables Limited theory Transition Phase • • • • • 1980s-1990s Rise of cognitive science Rejection of behaviorism Focus on unobservables Emphasis on models and theory Confirmatory Phase • • • • 2000s Rejection of exploratory methods Hypothesis-driven research Requirement of theory Our Current State? Deduction Deduction Deduction Quick Journal Analysis • Journal of Applied Psychology • 1971 Issue 1 vs. 2015 Issue 1 & 4 – 15 articles from each • Number of paragraphs – – – – Introduction Method Results Discussion • Have hypotheses Year Intro Method Results Discussion Hypoth. 1971 4.7 10 6.7 6.8 27%1 2015 24 18.5 10.6 14.9 93%2,3,4 1Three-fourths specific tests of theory: Equity and Herzberg. 2One paper tested theory without specifying hypotheses as such. 3Some use inductive language (explore) 4Hypotheses not tests of specific theories. Folly of Deductive Exclusiveness • “Deduction orders and rearranges our knowledge without adding to its content.” – More confidence in what we thought we knew. • “Induction can amplify and generalize our experiences, broaden and deepen our empirical knowledge.” – New knowledge Vickers, 2014 Pure Forms • Deduction – Hypotheses derived directly from theory – Hypothesis tests confirm/disconfirm theory • Induction – Generalizations made from observations • Abduction – Explanation/theory made from inductive generalization Current Pseudo-Deduction • • • • Data collected Hypotheses chosen to match data Theories argued to support hypothesis Hypotheses not tightly linked to theory – “Theory informed the hypothesis” – “Theory supports the hypothesis” • More abductive than deductive Science Based on Disclosure • Scientific report should describe what was done – What was assessed and when – When hypotheses were derived relative to data collection and analysis – Inductive, deductive, or abductive? Where Now? Inductive/Abductive Forces Prominent Scholars • Donald Hambrick, 2007 – “Too much of a good thing” – Why should facts await theories? • Edwin Locke, 2007 – “The case for inductive theory building” – Critique of deductive approach – Examples of successful induction-based theories Evolving Journal Practices • Special journal issues – Journal of Business and Psychology 2014 • – Rogelberg, Ryan, Schmitt, Spector, Zedeck Human Resource Management Review • – Woo, O’Boyle, Spector Journal of Organizational Behavior point/counterpoint: Theory • Journals allowing inductive papers – Academy of Management Discoveries • – Andrew Van de Ven Journal of Business and Psychology Research Integrity • • • • Confirmation bias concerns HARKing P mining (Simmons et al. 2011) Replication crisis Data Science – Data mining • • • Finding meaningful/useful data patterns Exploratory Inductive – Business intelligence – HR analytics – “Big data” Challenges To Pendulum Moving • Lack of knowledge – People only know current practice • Authors • Editors • Reviewers • Belief in deductive approach • Resistance to change Deductive Study • • • • • • • Need premises to confirm State theory Derive hypotheses directly from theory Design study to test hypotheses Collect data Test hypotheses Draw conclusion – Confirm/disconfirm theory Inductive Study • • • • • • Exploratory State purpose/questions Design study to address purpose Collect data Analyze data Interpret/generalize results Abduction • Finding best explanation for inductive observations • Explain results with existing theory • Explain results with new theory Doing and Reporting Inductive Research Inductive Introduction • • • • Clearly state purpose/question Review relevant background literature Note gaps in knowledge study will fill Is extensive literature review needed? – Not in health and natural sciences • Introductions state purpose and define terms • Limited background literature Heart failure is an extremely prevalent syndrome in developed and developing countries (Go et al., 2014). Outcomes associated with heart failure are poor, with patients experience increasing symptoms as the syndrome progresses (Lam and Smeltzer, 2012). Symptoms are responsible for a decline in functional status, deteriorating healthrelated quality of life (HRQL), repeated hospitalization, and early demise (Falk et al., 2013, Murthy and Lipman, 2011 and Song et al., 2010). A growing body of research demonstrates that self-care by patients can improve these outcomes (Ditewig et al., 2010, Jones et al., 2012 and Tung et al., 2013). Self-care involves a process of maintaining physiological stability by monitoring symptoms, adhering to the treatment regimen (self-care maintenance), and promptly identifying and responding to symptoms (self-care management) (Riegel and Dickson, 2008). Clinicians are challenged by the difficulties associated with engaging patients in self-care (Gardetto, 2011). Self-care requires that patients have knowledge and skills, both of which are influenced by cognition (Dickson et al., 2008). Cognitive impairment is recognized as an issue in 25–50% of adults with heart failure (Dodson et al., 2013, Gure et al., 2012 and Pressler, 2008). Most studies investigating the relationship between cognitive impairment and self-care have demonstrated that heart failure patients with cognitive impairment are poor at self-care. For example, Harkness et al. (2013) found that patients with mild cognitive impairment scored significantly lower in self-care management than those without cognitive impairment. Alosco et al. (2012) found that patients with lower (worse) scores on the Mini Mental Status Examination were more likely to fail in medication management, a dimension of self-care. Smeulders et al., 2010a and Smeulders et al., 2010b found that heart failure patients with better cognitive status benefitted more from a chronic disease self-management program compared to patients with poorer cognitive function. Only one investigative team found no relationship between cognition and self-care (Cameron et al., 2009), although in a subsequent study the same investigators (Cameron et al., 2010) found that heart failure patients with mild cognitive impairment exhibited lower self-care management and self-care confidence than patients without cognitive impairment. Hajduk et al. (2013) found no association between overall cognitive status and selfcare in heart failure patients, but when they analyzed specific domains, impaired memory was associated with poor self-care while executive function and processing speed were not. This inconsistency suggests that cognition is not a direct predictor of self-care behaviors in patients with heart failure. Mechanisms or pathways through which cognitive impairment affects self-care are worth clarifying because they may suggest targets for intervention. One potential mechanism is self-efficacy or task-specific confidence, which has been defined as confidence in the ability to perform the various self-care behaviors (e.g. confidence in one's ability to follow a low salt diet) (Riegel and Dickson, 2008). The situation specific theory of heart failure self-care (Riegel and Dickson, 2008 and Riegel et al., 2015) specifies that self-care maintenance (monitoring of heart failure symptoms and adhering to treatments) influences self-care management (the response of patients to signs and symptoms of a heart failure exacerbation) and that both are influenced by self-care confidence. Therefore, the overall purpose of this study was to test self-care confidence as mediating the relationship between predictors of selfcare and the self-care behaviors of maintenance and management (Riegel and Dickson, 2008). To date, few researchers have investigated the role of confidence in influencing self-care behaviors. Cene and colleagues (2013) found that perceived emotional and informational support was associated with better self-care maintenance and possibly better self-care management in a sample of heart failure patients. A similar result was found by Sayler et al. (2012) who showed that self-care confidence mediated the relationship between social support and self-care maintenance and between social support and self-care management. In a mixed method study Dickson et al. (2008) found that patients with lower self-care confidence and impaired cognition had lapses in self-care behaviors and were classified as “inconsistent” while those with higher self-care confidence and better cognition were better in self-care and were classified as “experts”. Building on prior studies illustrating that cognitive impairment and self-care confidence are both predictors of self-care behaviors and building on the situation specific theory of heart failure self-care that proposes confidence as a mediator of the relationship between self-care behaviors and its predictors, the specific objective of this study was to evaluate whether self-care confidence mediates the relationship between cognition and the self-care behaviors. Specifically we hypothesized that cognition affects self-care maintenance and management only indirectly by its influence on self-care confidence (Fig. 1). Inductive designs • • • • Basic designs much the same Collect more variables Bigger n to allow cross-validation Use methods that capture large amounts of data Inductive Analysis • Broader range of analyses in a study – More descriptive statistics – More inferential statistics – Fully explore data – Utilize graphical methods – Numerical analysis – Text analysis Data Mining • Family of techniques to find patterns in data • Knowledge discovery • Finding novel patterns – Forecasting – Understanding • Computer science + Statistics • New and old techniques Four Data Mining Problems • Data Matrix – Records by attributes – People by variables • Analysis of columns (attributes) 1. Association 2. Classification • Analysis of rows (records) 3. Clustering 4. Outlier analysis Association – Relationships among attributes • Correlations among continuous variables • Exploratory factor analysis: Underlying structure – Association rules mining (ARM) • • • • Items that go together If A, probability of B Support: Prevalence of A and of B Confidence: Co-occurrence of A and B Classification • Supervised: One column target attribute – Predict target attribute from other attributes – Criterion and predictors • Data used to “train” – Develop predictor model – Regression • Forward, Backward, Stepwise – ANOVA/MANOVA – Multilevel modeling Clustering • • • • Analysis of Records (Rows) Unsupervised Records sharing attributes Cluster analysis – – – – Based on attribute similarity Each case in one cluster Case more similar to own cluster Predict cluster membership Text Clustering • Based on word similarity • Vector space model – – – – – – – Word by document matrix List of all words in all documents Delete too common and too rare Each document has vector of words Vector similarity determines cluster membership Compile most common within-cluster words Interpret: Based on 10 most common words Gupta, 2014 Outlier Analysis • Records that are different from others • Generated by different mechanism • Used to detect deviance – Crime – Fraud • Statistical criteria – Univariate: 3 SD from Mean – Multivariate Distance • Euclidian distance • Standardized distance: Mahalanobis D Limitations To Inductive Approach Type 1 Error Problem • Likelihood increases with more tests • Solution – Cross-validation/replication – Supporting evidence in literature • Others found same results Interpretation Difficulties • Patterns might not be coherent – No framework to interpret results • Results disconnected list of facts • Solution – Abduction: Finding best explanation • Existing theory • Modifying theory • New theory What Makes a Good Inductive Paper? • Sound research question – Important – New – Unanswered • • • • Rigorous methodology Multiple methods Cross-validated Linked to existing literature Contribution To a Scientific Discipline • Testing old theory – Too many theories and not enough tests – Modal number of theory tests in AMR = 0 Kacmar & Whitfield 2000 • New findings: Exploration and Discovery • Andrew Van de Ven’s anomalies • Presenting new theory • Solution to practical problems • Academic-practice divide Concluding Thoughts • Authors should submit inductive papers. – Editors are more open than people assume. • Reviewers should evaluate papers on contribution beyond theory. • Data Mining literature has useful tools. • Exploratory research foundation of scientific progress. References Aggarwal, C. C. (2015). Data mining : The textbook. New York City: Springer. Douven, I. (2014). Abduction. The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (Spring 2014 edition). August 13, 2015. Retrieved from http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2014/entries/abduction/ Gupta, G. K. (2014). Introduction to data mining with case studies 3rd ed. Delhi, PHI Learning. Hambrick, D. C. (2007). The field of management's devotion to theory: Too much of a good thing? Academy of Management Journal, 50(6), 1346-1352. doi:10.5465/AMJ.2007.28166119 Kacmar, K. M., & Whitfield, J. M. (2000). An additional rating method for journal articles in the field of management. Organizational Research Methods, 3(4), 392-406. doi:10.1177/109442810034005 Locke, E. A. (2007). The case for inductive theory building. Journal of Management, 33(6), 867-890. doi:http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0149206307307636 Okasha, S. (2002). Philosophy of science: A very short introduction. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. Payne, D., & Trumbach, C. C. (2009). Data mining: Proprietary rights, people and proposals. Business Ethics: A European Review, 18(3), 241-252. doi:10.1111/j.14678608.2009.01560.x Rosenberg, A. (2012). Philosophy of science: A contemporary introduction (3rd ed.). New York City: Routledge. Simmons, J. P., Nelson, L. D., & Simonsohn, U. (2011). False-positive psychology: Undisclosed flexibility in data collection and analysis allows presenting anything as significant. Psychological Science, 22, 1359-1366. Vickers, J. (2014). The problem of induction. The Stanford encyclopedia of philosophy (Spring 2014 edition). August 13, 2015. Retrieved from http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2014/entries/induction-problem/