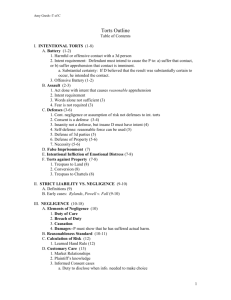

Fennell/Miles 3 (2008) - Black Law Students Association

advertisement