ENG207Paper2 - Krysta Jones's Electronic Portfolio

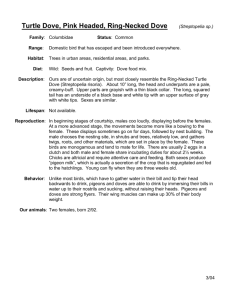

advertisement

Krysta Jones August 1, 2011 ENG 207/Section 001 Paper #2 The Woman’s Expression in “Daystar” While reading the poem “Daystar,” written by Rita Dove, its readers most likely do not ask thought-provoking questions like “Why did Dove write this?” or “What is the true meaning behind this poem?” but the poem has deeper meaning than what its outside layer portrays. Dove, an African American woman born in 1952, has not only viewed the racism of the United States society, but she has also seen how gender can or cannot play a role in the advancement of a person’s life (Rita Dove: The Poetry Foundation). The poem “Daystar” not only takes an outside perspective on the everyday life of a woman, but it closely relates to Dove’s family history. Dove uses the experiences of her life as a woman, and the knowledge gained from living in countries other than the United States, to depict the pressure and desire felt by mothers and/or wives on a daily basis. “She wanted a little room for thinking” (1) is how Dove begins her poem, and this automatically lets the reader know that the female subject of the poem has been troubled by something, or someone. This line alone portrays the gender of the poem, and it welcomes the reader into the life of this woman who desires to reflect on whatever has been troubling her. By using the pronoun “She,” as opposed to “I,” Dove looks in on the life of an unknown woman and not on the life of her own. Throughout the poem, we learn about this woman’s miniature escape away from her daughter, Liza, and all of the responsibilities that come with being a mother. The poem’s title also tells the reader that this stressed woman is in search for something not within reach. Taking a look at the role of gender, the life of Dove herself, and the knowledge shared by Jones 1 scholars Stein, Meitner, and Righelato, a deeper look at the intentions of “Daystar” can be analyzed. First, the poem’s origination must be explained before further analysis is placed on the topic of gender. “Daystar” comes from a book of poems written by Dove entitled Thomas and Beulah, which tells both the real and unreal stories of Dove’s maternal grandparents (Stein 64). Unlike Dove, who grew up during a time of women’s rights, her grandmother most likely did not have an admired career as a housewife. In discussing Thomas and Beulah, Stein explains, “It is almost painful to witness Thomas and Beulah, two people clearly devoted to each other, continually misinterpret each other's behavior” (70). Although “Daystar” is not necessarily written from an autobiographical perspective, Dove is using the research of her family and her own experiences to welcome us into the lives of the distressed Beulah. Beyond the already mentioned first line about how Beulah “wanted a little room for thinking (1),” there are many other evidences in the poem that prove this woman desires more than what she currently has. Even today, women are viewed as the main caretakers of their children and the ones who are expected to respond to the domestic duties at home, and this is what Beulah exemplifies. In the next lines of “Daystar,” obligations of motherhood are further explained as Dove writes, “but she saw diapers steaming on the line, /a doll slumped behind the door” (2-3). Both the diapers and the doll imply that it is Beulah’s job to take care of the laundry and clean up the mess that her children have left behind. Furthermore, the diction in the poem tells that Beulah is tired and in need of some sort of relief. In lines four and five, Dove uses the verb “lugged” to describe how a chair is being moved and tells that Beulah has to “sit out the children’s naps.” These lines suggest that this woman needs a break, even if it is for a short amount of time. “Sometimes there were things to watch/ Jones 2 the pinched armor of a vanished cricket,/a floating maple leaf”(6-8) not only lets the reader know that Beulah has sat in this position before, but the lines also show just how willing she is to escape her house, chores, and children to look at the simplicity of nature. Next, Dove expresses just how much Beulah wants to be on her own when she says, “she stared until she was assured/ when she closed her eyes/ she’d see only her own vivid blood”(911). Without being assured by friends or family, Beulah has to be assured by her own self that she is still the person she used to be. In responding to Dove’s word choice of “her own vivid blood” (11), Stein explains, “It is perhaps her best response to the "ultimately unanswerable" human question of "where I come from” (73-74). Beulah is tired and in search for answers to questions that are often avoided by worn-out and restless women. While Beulah only has “an hour, at best” (12) before her daughter appears “pouting from the top of the stairs” (13), she is still thinking about her child and the reaction that her child will give her when she returns inside. “And just what was mother doing/out back with the field mice? Why, building a palace.” (14-16) informs the reader that Beulah feels pressured and guilty when she is not with her children, or cleaning up their toys. These lines also imply that Beulah’s only appropriate role in society is to be a mother and nothing else. The word “palace” gives meaning to what little girls then and now are exposed to in stories, drawings, movies, etc. As most women do, Beulah realizes there are no knights in shining armor and no palaces unless she imaginatively builds them for herself. Similarly, Beulah feels the need to escape from her husband just as she does from her children. Although Thomas is “lurched into her,” Beulah still imagines the “place that was hers” and wishes that she could resort back to that moment in time. Dove writes, “she was nothing, /pure nothing, in the middle of the day.” (21-22) to show how powerful nothingness can be to a woman with an overwhelming amount of domestic responsibilities. Stein explains that in Dove’s Jones 3 poetry, she “…animates Beulah's yearning to break free of her circumscribed roles of wife and mother” (72). The poem is important not only to women as a whole, but it also lends a word of advice to men. By reading about Beulah’s “one hour” of relaxation and how it consumes her mind, even at night, men (who do not already) might recognize just how hard the work of a mother truly is. Any woman, no matter what age, race, sexual orientation, etc., can relate to the poem simply because the female sex is always expected to nurture, care, and respond to “pouting” whenever it happens. In an interview, Dove told Women in the Arts reporter, “When you are marginalized in any way—race, gender, age, class—you must learn to listen and pay attention very carefully if you are going to survive” (Rita Dove: The Poetry Foundation). By taking the time to recognize “her own vivid blood,” Beulah is able to survive the role of motherhood/wife. Not only does gender play a large role in “Daystar,” but Rita Dove’s life and method of writing about society’s downfalls are also essential in examining the poem. Thomas and Beulah was published in 1986, which was only three years before Dove’s first and only daughter, Aviva, was born (Comprehensive Biography of Rita Dove). Having children for any person is always something new and different to become used to, and it can be assumed that Dove’s composition of “Daystar” had something to do with how being a mother made her feel. Beulah’s daughter Liza awakens from a nap in the poem, and this probably correlated with Dove’s life at the time, since her daughter would have been three years of age. It is known that toddlers need naps, and they are also messy and energetic, which usually makes their caretakers very fatigued. In addition to the correlations between Dove’s daughter and age in the poem, there is also evidence of Dove’s personality and actions, as seen in interviews and journal articles written by her former students. Erika Meitner describes her experiences as one of Dove’s students and tells, Jones 4 “Rita’s home, for me, became a haven, a sanctuary where we were cared for and fed and where we pushed each other artistically” (664). This lets us know that like Beulah, Dove has a nurturing character, and that she rarely stops doing what she cares about (teaching). Meitner also explains the tendency of Dove to be adventurous and try new things like ballroom dancing and target shooting (665). Since Dove is able to explore new hobbies and meet new people because of her notable poetry writing and career, her poem “Daystar” might be a dedication to those women, like her grandmother, who were unable to do such things. In explaining Dove’s writing style Meitner writes, “Her poems have wide-ranging styles, often giving voice to the voiceless, and manage to imbue personal experiences with a larger sense of history and culture” (666). Although all poems of Dove cannot be proven to be autobiographical, there is a great deal of social awareness that comes along with them. In “Daystar,” Dove writes to express the stress and desire to relax that almost all mothers and wives feel, even today. In combining the two ideas of gender and self-expression, Beulah’s character most likely reflects some thoughts of Dove herself. Life is not easy, and it is certainly not easy for women in the United States, past or present. Scholar Pat Righelato explains that by writing, Dove is not “…not looking for supportive habitats in either black or feminist conclaves…” but that she is aimed at creating poetry based off of experiences and research (668). Although Dove does not search for applause by the communities of African Americans and/or women, she most certainly obtains it through her literature, which reflects her experiences. In comparing her writing to other notable authors, Righelato explains: It might seem surprising to link her most closely with Lowell and Ashbery, but she is like them in that her poetry is, in its entirety, a critique of American culture: like Lowell, Jones 5 she reveals history through the prism of the family; like Ashbery, fascinated by the materiality of the painted canvas, she accepts materialist culture as the medium of contemporary existence. Like both, she seeks new ways in which to express the autobiographical. (668) In conclusion, “Daystar” is a poem that can be examined from many critical standpoints. Whether a person criticizes it from a historical standpoint, or a psychological standpoint, Dove’s poem can most certainly be related to the gender of its main character. Overall, Dove’s experiences in her own life and the research of others’ are two of her prime techniques in writing her world-famous poetry. Jones 6 Works Cited "Comprehensive Biography of Rita Dove." The Rita Dove Home Page. University of Virginia. Web. 27 July 2011. <http://people.virginia.edu/~rfd4b/compbio.html>. Meither, Erika. "On Rita Dove." Callaloo 31.3 (2008): 662-666. Project MUSE. Web. 21 Jan. 2011. <http://muse.jhu.edu/>. 26 July 2011. Righelato, Pat. "From Understanding Rita Dove." Callaloo 31.3 (2008): 668-668. Project MUSE. Web. 21 Jan. 2011. <http://muse.jhu.edu/>. 26 July 2011. "Rita Dove: The Poetry Foundation." Rita Dove. Poetry Foundation, 2011. Web. 27 July 2011. <http://www.poetryfoundation.org/bio/rita-dove>. Stein, Kevin. “Lives in Motion: Multiple Perspectives in Rita Dove's Poetry.” Mississippi Review 23.2 (1995): 51-79. JSTOR. Web. 27 July 2011. Jones 7