[DOC] Chapter_03

advertisement

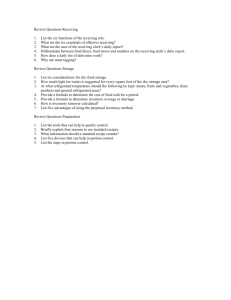

![[DOC] Chapter_03](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/009084081_1-362a0e8fc0f36e2246129c541f6b43be-768x994.png)