B40.2302 Class #8

advertisement

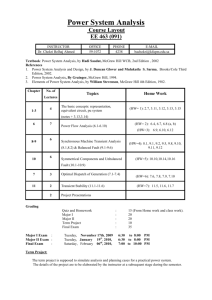

14- 1 B40.2302 Class #8 BM6 chapters 16.5-16.8,18.1-18.3,18.5,19 16.5-16.8: Dividend relevance under taxes etc. 18.1-18.3, 18.5: Capital structure relevance under taxes and financial distress 19: Valuation under financing effects Based on slides created by Matthew Will Modified 10/31/2001 by Jeffrey Wurgler Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 Principles of Corporate Finance Brealey and Myers Sixth Edition The Dividend Controversy Slides by Matthew Will, Jeffrey Wurgler Irwin/McGraw Hill Chapter 16.5-16.8 ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 3 Topics Covered Views on dividend relevance The “Rightists” (dividends increase value) The “Radical Left” (dividends decrease value) The “Middle-of-the-Roaders” (little or no effect) Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 4 Dividends Increase Value A “rightist” (high-payout) view … the considered and continuous verdict of the stock market is overwhelmingly in favor of liberal dividends as against niggardly ones… Benjamin Graham and David Dodd Security Analysis (1951) (1st ed. 1934) Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 5 Dividends Increase Value Rightist argument: M&M ignore risk Dividends are cash in hand, but capital gains are not “Bird in hand versus bird in bush” So isn’t the dividend to be preferred? Questionable argument Declaring high dividend makes (residual) capital gain component more risky, overall risk to shareholders does not change Can get dividend-like “bird in hand” whenever you like, just by selling some of your stock M&M assume efficient capital market: $1 in dividend would otherwise be capitalized at $1 in share price. So long as this is true, the “bird in hand” argument is invalid. If this is not true (as Graham and Dodd imply), argument is valid. Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 6 Dividends Increase Value Rightist argument: There are “clienteles” that prefer dividends Some financial institutions cannot hold stocks that do not have established dividend records Trusts and endowments may be discouraged from spending capital gains (which may be viewed as “principal”) but allowed to spend dividends (may be viewed as “income”) Retirees(?)/Small investors(?) may prefer to spend from their AT&T dividend checks rather than sell a few shares every month. (Reduces transaction costs, inconvenience) Corporations pay corporate income tax on only 30% of dividends they receive, but 100% of capital gains. The demand of these “dividend clienteles” may increase the price of a dividend-paying stock But… Unclear whether any particular firm can benefit by increasing dividends. There may already be enough high-dividend stocks to choose from. Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 7 Dividends Increase Value Rightist argument: Dividends can’t be wasted Investors may not trust managers to invest retained earnings wisely Firms that refuse to pay out cash may sell at a discount Comments In this case dividend decision is tied to investment decision May have particular merit in countries with poor corporate governance systems Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 8 Dividends Decrease Value Leftist (low-payout) argument: Taxes If dividends are taxed more heavily than capital gains, investors dislike dividends. Firms should pay low dividend, retain cash or repurchase shares Investors should require higher pre-tax return on dividend-paying stocks (i.e, dividend-paying stocks sell at a discount price) Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 9 Dividends decrease value Effect of investor taxes (50% dividend, 20% capital gain) on share prices and returns Firm A Firm B Next year' s price Dividend (no dividend) 112.50 0 (high dividend) 102.50 10 Total pretax payoff Today' s stock price Capital gain 112.50 100 12.50 112.50 96.67 5.83 Pretax rate of return (%) Tax on div @ 50% 12.5 100 100 12.5 0 Tax on Cap Gain @ 20% .20 12.50 2.50 Total After Tax income (0 12.50) 2.50 10 (div cap gain - taxes) 10 After tax rate of return (%) 100 10.0 100 Irwin/McGraw Hill 15.83 100 96.67 16.4 .50 10 5.00 .20 5.83 1.17 (10 5.83) (5 1.17) 9.66 9.66 100 96.67 10.0 ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 10 Dividends decrease value 1998 Marginal Income Tax Brackets Income Bracket Marginal Tax Rate 15% 28 31 36 39.6 Single $0 - $25,350 25,351 - 61,400 61,401 - 128,100 128,101 - 278,450 over 278,450 Married (joint return) $0 - $42,350 42,351 - 102,300 102,301 - 155,950 155,951 - 278,450 over 278,450 • Dividends are taxed at the personal income rate • Capital gains are, for most investors, taxed at 28% • High-tax-bracket investors therefore still prefer capital gains Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 11 Dividends decrease value Empirical evidence on dividends, prices, returns: • Mixed. • Generally a positive relationship between dividend yield and pre-tax returns, as predicted by “leftists” • But statistically unreliable Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 12 Middle of the road Maybe M&M conclusion of irrelevance is right even when some of the assumptions are relaxed: • High- or low-payout clienteles may exist, but they are already satisfied, so no firm can increase its value by changing dividends • This “middle of the road” view argues that dividends have little or no effect on value Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 Principles of Corporate Finance Brealey and Myers Sixth Edition How Much Should a Firm Borrow? Slides by Matthew Will, Jeffrey Wurgler Irwin/McGraw Hill Chapter 18.118.3, 18.5 ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 14 Topics Covered Corporate Taxes Corporate and Personal Taxes Costs of Financial Distress Financial distress games The “trade-off theory” of capital structure Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 15 Corporate Taxes Main advantage of debt in U.S.: Corporations can deduct interest Whereas retained earnings and dividends are taxed at the corporate level Thus, more cash left for investors if firm uses debt finance Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 16 Corporate Taxes Example – Firm U is unlevered, firm L is levered. Firms have same investment policy (so same operating cash flows). U L 1,000 1,000 0 80 1,000 920 350 322 Net Income to shhs $650 $598 EBIT Interest Pmt Pretax Income Tax @ Tc= 35% Net to bhhs Total to investors 80 650 Interest tax shield (.35*interest) Irwin/McGraw Hill 678 28 ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 17 Corporate Taxes What is present value of tax shield? • If the same savings occur every year, value as a perpetuity • If the savings are as risky as the debt, discount at cost of debt • Under these assumptions: PV of Tax Shield = D x rD x Tc = D x Tc rD Example (D = 1000, rD =.10, Tc=.35): Yearly savings = 1000 x (.10) x (.35) = $35 PV Perpetual Tax Shield @ 10% = 35 / .10 = 1000*.35 = $350 Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 18 Corporate Taxes Taxes don’t change the total size of the pretax “pizza.” But now the government gets a slice. Government’s slice is smaller (and investors’ slices are bigger) when debt is used. M&M proposition I with corporate taxes: Firm Value = Value of All Equity Firm + PV(Tax Shield) … and in special case where debt is permanent … Firm Value = Value of All Equity Firm + Tc*D Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 19 Corporate Taxes So why not 100% debt, then, or close to it? Maybe looking at corporate and personal taxation will uncover a personal tax disadvantage to borrowing (to offset the corporate tax advantage) Or, maybe firms that borrow incur other costs – such as costs of financial distress – that offset interest tax shield Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 20 Corporate and Personal Taxes TC TP TPE Corporate tax rate Personal tax rate on interest income Personal tax rate on Equity income (= TP if all equity income comes in form of cash dividends, but < TP if comes as capital gains, << if they are deferred) --------------------------------------------------------------------------$1 in operating income paid as interest: = $(1 – TP) to bondholder (escapes corporate tax) $1 in operating income paid as equity income: = $(1 – TPE)*(1 – TC) (hit by corporate tax, then personal tax) Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 21 Corporate and Personal Taxes Relative Tax Advantage of Debt over Equity = 1-TP (1-TPE)*(1-TC) Tax advantage RA > 1 Debt RA < 1 Equity Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 22 Corporate and Personal Taxes Example 1 Interest Equity income Income before tax 1.00 1.00 Corp taxes Tc=.35 0.00 0.35 To investor 1.00 0.65 Pers. taxes TP =.40, TPE=.10 0.40 0.065 Income after all taxes 0.585 RA = 1.025 Irwin/McGraw Hill 0.60 Advantage: Debt (barely) ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 23 Corporate and Personal Taxes Example 2 Interest Equity income Income before tax 1.00 1.00 Corp taxes Tc=.35 0.00 0.35 To investor 1.00 0.65 Pers. taxes TP =.40, TPE= 0 0.40 0.00 Income after all taxes 0.65 0.60 RA = 0.923 Advantage: Equity Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 24 Corporate and Personal Taxes So then … equity or debt? Merton Miller’s argument: Suppose TPE = 0 and TP varies across investors. Then • Economy-wide tax-minimizing mix of debt and equity depends on distribution of personal tax rates • But there still may be are no tax gains left for individual firms to get by varying their own leverage - “Low-tax” investors already hold all the bonds they want - If “marginal investor” has high tax rate, may be no tax gain left from issuing debt to him! - Current tax law still seems to favor borrowing, though (TPE not as low as Miller assumed) Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 25 Costs of Financial Distress Costs of Financial Distress - Costs arising from bankruptcy or distorted business decisions on the brink of bankruptcy. Firm value = Irwin/McGraw Hill Value of All Equity Firm + PV(Tax Shield) - PV(Costs of Financial Distress) ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 26 Trade-off Theory Market Value Costs of financial distress PV of interest tax shields Value of levered firm Value if All Equity Optimal amount of debt Irwin/McGraw Hill Debt ratio ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 27 Costs of Financial Distress Bankruptcy is not costly in itself; bankruptcy costs are the cost of using this legal mechanism Bankruptcy costs and costs of financial distress are borne by shareholders Creditors foresee the costs and foresee that they will pay them if default occurs For this, they demand higher interest rates in advance This reduces the present market value of shares Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 28 Costs of Financial Distress Direct costs (legal, administrative fees) Manville (1982, asbestos): $200m on fees Eastern Airlines (1989): $114m on fees On average, direct costs = 3% of book assets, or 20% of market equity in year prior to bankruptcy Indirect costs Customers may stray if firm may not be around, suppliers may be unwilling to give much effort to firm’s account, good employees hard to attract … Hard to measure, but probably large Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 29 Costs of Financial Distress US bankruptcy procedures Chapter 11 Aims to rehabilitate firm; protect value of assets while reorganization plan is worked out; used more by large, public companies Chapter 7 Aims to dismember firm; assets are auctioned and creditors paid off (usually) according to seniority; used more by small companies Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 30 Costs of Financial Distress Financial distress may be costly even without formal bankruptcy When a firm is in trouble, both shareholders and bondholders want it to recover, but otherwise their interests may conflict Shareholders may pursue self-interest rather than the usual objective of maximizing overall market value Shareholders may play “games” at creditors’ expense These games can reduce overall value Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 31 Financial distress games Circular File Company has $50 of 1-year debt. Circular File Company (Book Values) Net W.C. 20 50 Bonds outstanding Fixed assets 80 50 Common stock Total assets 100 100 Total value Circular File Company (Market Values) Net W.C. 20 25 Bonds outstanding Fixed assets 10 5 Common stock Total assets 30 30 Total value Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 32 Financial distress games Game #1: Risk shifting Circular File Company may invest $10 as follows: Now Possible Payoffs Next Year $120 (10% probabilit y) Invest $10 $0 (90% probabilit y) Suppose NPV of the project is (-$2). What is the effect on the market values? Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 33 Financial distress games Circular File Company (Market Values - post project) Net W.C. 10 20 Bonds outstanding Fixed assets 18 8 Common stock Total assets 28 28 Total liabilities Firm value falls by $2 But equity gains $3 (say) Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 34 Financial distress games Game #2: Refusing to contribute equity capital Suppose NPV = $5 project (costs 10 new equity, returns 15) Circular File Company (Market Values - post project) Net W.C. 20 33 Bonds outstanding Fixed assets 25 12 Common stock Total assets 45 45 Total liabilities While firm value rises, the lack of a high potential payoff for shareholders actually causes a decrease in equity value. Shareholders will therefore resist the project Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 35 Financial distress games Other games Cash In and Run Playing for Time Bait and Switch Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 36 Trade-off theory redux Trade-off theory argues that optimal debt ratios vary from firm to firm PV (tax shields) vary • Depends on level and risk of taxable income PV (costs of financial distress) vary • Tangible assets lose least value in distress • So can take on more debt So trade-off theory may explain why different firms have different capital structures Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 Principles of Corporate Finance Brealey and Myers Sixth Edition Financing and Valuation Slides by Matthew Will, Jeffrey Wurgler Irwin/McGraw Hill Chapter 19 ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 38 Topics Covered After-Tax WACC Using WACC: Tricks of the Trade Adjusting WACC when risks change Adjusted Present Value (APV) Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 39 After Tax WACC The tax shield of interest reduces the after-tax weighted-average cost of capital. The amount of the reduction depends on Tc D E WACC rD (1 Tc) rE V V Note WACC < r (our previous “opportunity cost of capital”) Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 40 After Tax WACC So WACC incorporates the tax advantages of debt financing in lower discount rate Note that all variables in WACC refer to whole firm So after-tax WACC gives right discount rate only for new projects that are just like the firm’s “average” Would need to be adjusted for projects whose acceptance would cause a change in the firm’s overall debt ratio (we’ll show how later) Would need to be adjusted for safer or riskier projects (we won’t show how) Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 41 After Tax WACC Example - Sangria Corporation The firm has a marginal tax rate Tc of 35%. The cost of equity is 14.6% and the pretax cost of debt is 8%. Given the following market value balance sheets, what is the after tax WACC? Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 42 After Tax WACC Example - Sangria Corporation - continued Given: Tc=35%, rE=.146, rD=.08, and the market value balance sheet: Balance Sheet (Market Value, millions) Assets 125 50 Debt (D) 75 Equity (E) Total assets 125 125 Firm value (V) Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 43 After Tax WACC Example - Sangria Corporation - continued Debt ratio = (D/V) = 50/125 = .4 Equity ratio = (E/V) = 75/125 = .6 Plug and chug to solve for WACC … D E WACC rD (1 Tc) rE V V Irwin/McGraw Hill = .1084 ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 44 After Tax WACC Example - Sangria Corporation - continued How to use the WACC of 10.84%? Suppose company has following investment opportunity: can invest in an ice-crushing machine with perpetual, pretax cash flows of $2.085 million per year. Given an initial investment of $12.5 million, and assuming that firm will finance it without changing its current debt ratio, what is the value of the opportunity? Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 45 After Tax WACC Example - Sangria Corporation - continued The company would like to invest in a perpetual ice-crushing machine with cash flows of $2.085 million per year pre-tax. Given an initial investment of $12.5 million, what is the value of the machine? Cash Flows Pretax cash flow Tax @ 35% After-tax cash flow Irwin/McGraw Hill 2.085 0.730 $1.355 million ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 46 After Tax WACC Example - Sangria Corporation – contd. Discount after-tax cash flow (not accounting for debt tax shield) at after-tax WACC. I.e., calculate taxes as if company were all-equity financed. Value of debt tax shield is already being counted in the after-tax WACC! 1.355 NPV 12.5 .1084 0 Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 47 After Tax WACC Interim review: After-tax WACC methodology is one way to calculate value when interest is tax-deductible Required assumptions: 1. Project’s business risks are same as firm average 2. Project supports the same fraction of D/V as overall firm Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 48 WACC Tricks of the Trade What about other forms of financing? Preferred stock (P) and other forms of financing are easily included D P E WACC rD (1 Tc) rP rE V V V In this case, V = D + P + E Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 49 WACC Tricks of the Trade How do you get the inputs? Can use stock market data to estimate rE rD , debt and equity ratios usually easy … … Unless the debt is junk. If default risk is high, promised yield overstates true cost, true expected return No easy solution. (Try sensitivity analysis, see if your choice makes a difference.) Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 50 WACC Tricks of the Trade Some common mistakes D E WACC rD (1 Tc) rE V V “My firm could borrow 90% of project cost if I want. So D/V=.9, E/V=.1. My firm’s cost of debt is 8%, and cost of equity is 15%. When I discount at WACC = .08*(1-.35)*.9+.15*.1=6.2%, project looks great!” Mistakes: Formula doesn’t apply if project isn’t same as firm. E.g. if firm isn’t already 90% debt financed, can’t use formula without making adjustment. Even if firm was going to lever up to 90% debt, its cost of capital would not decline to 6.2%. The increased leverage would increase the cost of debt and the cost of equity, too. Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 51 WACC for U.S. oil industry Percent (nominal) 30 Cost of Equity WACC Treasury Rate 25 20 15 10 5 Irwin/McGraw Hill 98 19 95 19 92 19 89 19 86 19 83 19 80 19 77 19 74 19 71 19 68 19 19 65 0 ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 52 WACC(y?) adjustments What if project is not financed at same D/E proportions as firm? • Can’t just plow ahead with regular WACC. Need to adjust. • Three-step process: 1. Calculate opportunity cost of capital using firm debt ratio r = rD(D/V) + rE (E/V) 2. Estimate project cost of debt rD at project debt-equity ratio, and then use this and r to calculate project cost of equity rE rE = r + (r - rD)(D/E) 3. Recalculate WACC at project rD , rE , debt ratio Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 53 WACC(y?) adjustments Sangria contd. What if project supports 20% D/V, not 40% D/V like overall firm? 1. Calculate opportunity cost of capital using firm debt ratio r = rD(D/V) + rE (E/V) = .08(.4) + .146(.6) = .12 2. Estimate project cost of debt rD at project debt-equity ratio, and then use this and r to calculate project cost of equity rE rE = r + (r - rD)(D/E) = .12 + (.12-.08)(.25) = .13 • Notes: assumed rD stays at 8%; D/V =.20 D/E = .25 3. Recalculate WACC at project rD , rE , debt ratio WACC = .08(1-.35)(.2) + .13(.8) = .1140 (vs. .1084 orig.) Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 54 Adjusted Present Value APV is second way to incorporate tax advantages of debt WACC messes around with discount rate, while APV explicitly adjusts the cash flows and present values. APV = base-case NPV + PV(Financing effects) “Base case” = All-equity NPV. “Financing effects” = costs/benefits due to financing (interest tax shields, security issue costs) Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 55 Adjusted Present Value Example (financing effect = issue cost): Project A has a base-case NPV of $150,000. But in order to finance the project we must issue stock, which costs $200,000 in fees. Project NPV = 150,000 Stock issue cost = -200,000 APV - 50,000 APV < 0 don’t do it Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 56 Adjusted Present Value Example (financing effect = tax shield): Project B has a base-case NPV of -$100,000. If financed with debt, however, it adds a tax shield with a PV of $140,000. Project NPV = PV(tax shield) = APV -100,000 140,000 40,000 APV > 0 do it (but wouldn’t do it if all-equity) Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000 14- 57 After-Tax WACC vs. APV With consistent assumptions, get same answer. WACC assumes constant debt ratio , but then don’t have to value tax shield explicitly APV lets tax shields vary over time , but have to calculate them yourself . APV more flexible: can handle other financing effects besides interest tax shields Irwin/McGraw Hill ©The McGraw-Hill Companies, Inc., 2000