Peterson '15 - Open Evidence Project

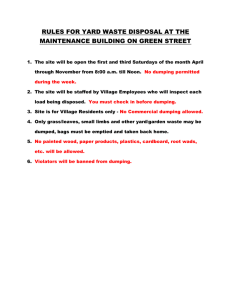

advertisement