The Long and Winding Road - Maryland Assessment Research

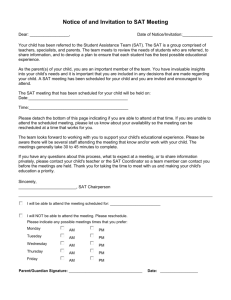

advertisement

The Long and Winding Road: Researching the Validity of the SAT Wayne Camara, Jennifer Kobrin, Krista Mattern, Brian Patterson, & Emily Shaw Ninth Annual Maryland Assessment Conference: The Concept of Validity: Revisions, New Directions & Applications October 9th and 10th, 2008 Outline of Presentation Planning the Journey. Mapping out the research agenda. Targeting the sample of institutions. Making Connections with Institutions. Validity evidence is only as good as the data we collect. Issues and lessons learned in initiating and maintaining contact with institutions to get good quality data. Detours and Statistical Fun. Cleaning the data. All institutions are not the same. How to aggregate and compare SAT validity coefficients across diverse institutions. “To correct or not to correct?” Restriction of Range. Deciding how to get from Point A to Point B. There are numerous ways to look at the relationship between the SAT, HSGPA and other variables, and college grades and each may give a different picture. A Bumpy Road. The fairness issue: differential validity and differential prediction 2 Planning the Journey • Mapping out the research agenda. Targeting the sample of institutions. 3 Sampling Plan • Size • The population of Small (750 to 1,999 undergrads) colleges: 726 institutions Medium to Large (2,000 to 7,499) Large (7,500 to 14,999) receiving 200 or more Very large (15,000 or more) SAT score reports in • Selectivity 2005. under 50% of applicants admitted 50 to 75% over 75% West • The target sample of colleges: stratified target • Control Public sample was 150 Private institutions on various • Region of the Country characteristics Mid-Atlantic Midwest (public/private, region, New England admission selectivity, South Southwest and size) 4 • Example of our Sampling Plan Guide The Target Schools Region Public/Private Private Middle States Public Private Midwestern Public 5 Selectivity Small Medium to Large Difference Between Sample and Target Large Very Large Small Medium to Large Large Very Large 50 to 75% 2 2 1 1 0 -1 -1 -1 over 75% 1 2 1 0 -1 -2 -1 * under 50% 0 3 1 0 * -1 -1 * 50 to 75% 2 5 1 1 -2 -4 0 1 over 75% 0 2 1 0 * -1 -1 * under 50% 0 1 1 0 * -1 -1 1 50 to 75% 1 1 1 0 3 0 0 * over 75% 1 4 0 0 -1 0 * * under 50% 1 1 1 0 0 0 0 * 50 to 75% 0 0 1 3 * * -1 -3 over 75% 1 1 2 5 -1 -1 0 -3 under 50% 0 0 1 1 * * -1 -1 Note. In the difference section, negative numbers indicate the number of schools still needed to fulfill the target; positive numbers indicate the number of schools over-sampled; the symbol * indicates zero school in the target and no school actually sampled; "0" indicates the number of schools sampled matched the target. Making Connections with Institutions • Validity evidence is only as good as the data we collect. Issues and lessons learned in initiating and maintaining contact with institutions to get good quality data. 6 Institutions were Recruited Via: • Email invites from CB staff with relationships • Conference Exhibit Booths: • Association for Institutional Research (AIR) • National Association of College Admission Counseling (NACAC) • CB National Forum; 7 CB Regional Forums • American Educational Research Association (AERA) • Print announcements in CB and AIR publications 7 Recruitment 8 • Recruitment took place between 2005-2007 • In order to participate, institutions had to have at least 250 first-year, first-time students that entered in the Fall of 2006 • Also, at least 75 students with SAT scores are necessary to conduct an Admitted Class Evaluation Service (ACES) study. ACES served as the data portal between the institution and the College Board. • Institutions designated a key contact who received a stipend of $2,000 - $2,500 for loading data into ACES (Direct costs =$800,000) ACES • The Admitted Class Evaluation Service (ACES) is a free online service that predicts how admitted students will perform at a college or university generally, and how successful students will be in specific classes. http://www.collegeboard.com/highered/apr/aces/aces.html Click here to request a study 9 Required Data for Each Student For Matching: • SSN • Course names for each semester • Last Name • The number of credits each course is worth • First Name • Date of Birth • Course semester/trimester indication • Gender • Course grades for each semester Optional, but recommended: • College/universityassigned unique ID 10 Necessary for the validity research: • First-year GPA Whether the student returned to the institution for the Fall of 2007 (submitted before 10/15/07) Institutional Characteristics Variable Region Selectivity Sample Population MRO 15% 16% MSRO 24% 18% NERO 22% 13% SRO 11% 25% SWRO 11% 10% WRO 17% 18% under 50% 24% 20% 50 to 75% 54% 44% over 75% 23% 36% Small: 750 to 1,999 undergrads 20% 18% Medium to Large: 2,000 to 7,499 undergrads 39% 43% Large: 7,500 to 14,999 undergrads 21% 20% Very large: 15,000 or more undergrads 20% 19% Public 43% 57% Private 57% 43% Size Control 11 Detours and Statistical Fun • Cleaning the data • A Volkswagon is not a Hummer (or all institutions are not the same)! Necessary to logically aggregate and compare SAT validity coefficients across diverse institutions • “To correct or not to correct?” 12 Cleaning the Data after ACES Processing Student Level Checks to Remain in the Study • Student earned enough credit to constitute completion of a full academic year • Student took the SAT after March 2005 (SAT W score) • Student indicated their HSGPA on the SAT Questionnaire (when registering for the SAT) • Student had a valid FYGPA Institution Level Checks to Remain in the Study • Check for institutions with high proportion of zero FYGPA (should some be missing or null?) • Grading system makes sense (e.g. an institution submitted a file with no failing grades) • Recoding variables for consistency (e.g. fall semester or fall trimester or fall quarter = term 1 for placement analyses) 13 Issues: Student matching (institution to CB name, dob, ssn), loss of students who did not complete semester ( year) makes persistence difficult to track SAT Validity Study • In several instances, individual institutions were contacted to attempt to remedy data issues • After cleaning the data and removing cases with missing data, the final sample included: • 110 colleges (of the original 114 institutions) participated in Validity Study • 151,316 students (of the original 196,356) were analyzed 14 Aggregating and Comparing SAT Validity Coefficients across Diverse Institutions 15 Boxplots of Standardized Regression Coefficients for Institutions in SAT Validity Study Sample To account for the variability across institutions, the following procedures were followed: (1) Compute separate correlations for each institution (2) Apply a multivariate correction for restriction of range to each set of correlations separately; and (3) Compute a set of average correlations, weighted by the size of the institutionspecific sample. 16 So why do we adjust a correlation? If a college admitted all students irrespective of SAT scores you would find a normal distribution of scores and FGPA and a higher correlation than you observe after selection. The more selective the college, the less likely they are to admit many students with low SAT scores – and they may have far less students with low FGPA than in a population. 17 Restriction of Range The result is that the entering class is restricted (to higher scoring students) which makes the correlation lower than it is in a representative population. .70 18 We adjust a raw correlation to account for this restriction and to get us an estimate of the true validity of any measure. The same thing occurs anytime we restrict one variable in selection. More on Restriction of Range • Most believe that correcting for RoR is an appropriate technique, however, some people (mistakenly) think you are manipulating the data • Others believe that if the assumptions of the correction cannot be directly verified, corrections should not be applied. • Best practice is if you do correct correlations, to report both: Standard 1.18 in the Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing (p. 21) states, “When statistical adjustments, such as those for restriction of range or attenuation, are made, both adjusted and unadjusted coefficients, as well as the specific procedure used, and all statistics used in the adjustment, should be reported.” • Ultimately, the decision to correct should be based on the purpose of the study and the types of interpretations that will be made (compare predictors, explain total variance accounted for in a model, etc.). Reporting both adjusted and unadjusted correlations is normally appropriate in selection. 19 In the current study: • We employed the Pearson-Lawley multivariate correction • The population was defined as the 2006 College Bound Seniors cohort • Any student graduating from HS in 2006 and took the SAT • Computed the variance-covariance matrix of SAT-M, SAT-CR, SAT-W, and HSGPA scores using students with complete records 20 Descriptive Statistics of the Restricted Sample as compared to the Population 21 Predictor Sample Mean SD Population Mean SD HSGPA SAT-CR SAT-M SAT-W 3.60 560 579 554 0.50 95.7 96.7 94.3 3.33 507 520 500 0.63 110.0 113.5 107.2 FYGPA 2.97 0.71 -- -- Correlations of Predictors with FYGPA Predictors 22 Unadjusted R R* HSGPA 0.36 0.54 SAT W 0.33 0.51 SAT CR 0.29 0.48 SAT M 0.26 0.47 SAT CR+M 0.32 0.51 SAT CR+M+W 0.35 0.53 HSGPA + SAT 0.46 0.62 Note. N=151,316. * Correlations corrected for restriction of range, pooled within-institution correlations Correlations Aggregated by Institutional Characteristics N SAT HSGPA SAT+HSGPA Private 45,786 0.57 0.55 0.65 Public 105,530 0.52 0.53 0.61 SELECTIVITY Under 50% 27,272 0.58 0.55 0.65 50-75% 84,433 0.53 0.54 0.62 >75% 39,611 0.51 0.54 0.60 CONTROL 23 * Correlations corrected for restriction of range, pooled within-institution correlations Other Possible Corrections that were not Applied in the Current Study • Criterion Unreliability (attenuation) – college grades are not perfectly reliable • In order to compare with past results, we did not correct for attentuation • Results would have shown even larger correlations • Predictor Unreliability • SAT scores are not perfectly reliable, but they are pretty close (reliability in 90s for CR & M and high 80s for W) • Since admission decisions are made with imperfect measures, did not correct for predictor unreliability • Course Difficulty • Students don’t take all of the same courses. Courses are not all of the same difficulty (see Sackett and Berry, 2008) 24 • Placement study will examine whether or not to control for course difficulty Deciding How to Get from Point A to Point B • There are numerous ways to look at the relationship between the SAT, HSGPA and other variables, and college grades and each may give a different picture. 25 Many ways to Examine and Visually Present the Predictive Validity of the SAT • In addition to bivariate correlations and multiple correlations which indicate the predictive power of an individual measure or multiple measures used in concert, there are other ways to analyze/present the data. • Regression analyses – examination of Beta weights (as opposed to raw regression coefficients) • Including additional predictors* • Incremental validity • Order matters* • Mean level differences by performance bands • Alternative outcomes • Individual course grades rather than FYGPA 26 Though some of these may be more accessible to laypersons, if used improperly, they may be misleading… The slope of the regression line, which shows the expected increase in FYGPA associated with increasing SAT scores. • More readily understood than a correlation coefficient • When looking at multiple variables, Beta weights answers the question: Which of the independent variables have a greater effect on the dependent variable in multiple regression analysis? • Can look at the effect of additional variables after first taking into account other variables 27 4.00 r = .37 3.00 2.00 FGPA 1.00 0.00 200 300 400 500 SAT-Math 600 700 800 However the Results may need to be Interpreted with Caution! It should be clear now that high multicollinearity may lead not only to serious distortions in the estimations of regression coefficients but also to reversals in their signs. Therefore, the presence of high collinearity poses a serious threat to the interpretation of the regression coefficients as indices of effects (Pedhazur, 1982, p. 246). 28 The SAT is Cursed: University of California Study (2001) • Examining UC data, Geiser and Studley (2001) found that SAT II scores and HSGPA together account for 22.2% of the variance in FYGPA in the pooled, 4-year data. • Adding SAT I into the equation improves the prediction by an increment of only 0.1% in the pooled, 4-year data. Support using SAT II scores and HSGPA, not SAT I scores. • However, they fail to mention that similar findings can be seen with the SAT II subject tests. • SAT I scores and HSGPA together account for 20.8% of the variance • Adding SAT II improves the prediction by an increment of 1.5% THE REASON: SAT I and SAT II scores are highly correlated (redundant) – issue of multicollinearity! 29 Reverse the Curse: New UC Study (2007): 30 • Agranow & Studley (2007) reached different conclusions • Examined the predictive validity of the new SAT for 33,356 students who • Completed the new SAT • Enrolled in a UC campus in the fall of 2006 • Results compared to previous UC study using the old SAT in 2004 • Comparisons based on how well each measure predicted Freshman GPA at UC (based on a model with all three SAT sections and HSGPA entered simultaneously predicting FYGPA) • SAT Critical Reading and Math slightly more predictive in 2006 than in 2004 • SAT Writing slightly more predictive than the other SAT sections • SAT Writing (in 2006) slightly more predictive than Writing Subject Test had been (in 2004) • In 2004 study, High School GPA was slightly more predictive than SAT V+M • In 2006 study, SAT CR+M+W was slightly more predictive than High School GPA The SAT is a wealth test: University of California Study (2001) • Another conclusion from the Geiser and Studley (2001) study was that after controlling for not only HSGPA and SAT II scores, but also parental education and family income, SAT I scores did not improve the prediction. • Claimed that the predictive power of the SAT I essentially drops to zero when SES is controlled for in a regression analysis. • Conclusion - SAT is a wealth test – even though its incremental validity was already essentially zero before SES variables were added! 31 THE REASON, again: SAT I and SAT II scores are highly correlated (redundant) – issue of multicollinearity! …However, the media had a different take. Sampling of SAT-Related SES Articles in the Popular Press “SAT scores tied to income level locally, nationally” (Washington Examiner, August 31, 2006) “Parents' education best SAT predictor” (United Press International, May 4, 2006) “SAT measures money, not minds” (Yale Herald, November 15, 2002) 32 Disproving the Myths about Testing (often perpetuated by the media) Sackett et al., 2007 • Computed the correlation of college grades and SAT scores partialling out SES to determine the degree to which controlling for SES reduced the correlation. • Contrary to the assertion of many critics, statistically controlling for SES only slightly reduced the estimated test-grade correlation (0.47 to 0.44) Zwick & Greif Green, 2007 • The correlation of SAT scores and SES factors is smaller when computed within high school rather than across high schools. • The correlation of HSGPA and SES factors is slightly larger within high schools compared to across high schools. Mattern, Shaw & Williams, 2008 • Across high schools, correlations of SAT and SES were about 2.2 times larger than the correlations of high school performance and SES. 33 • Within high school and aggregated, the SAT-SES correlations were only 1.4 times larger than the high school performance-SES correlations. Whoever Sits in the Front Seat Determines the Result Incremental Validity Example R1 R2 ΔR HSGPA (Add SAT-CR + SAT-M) 0.54 0.61 0.07 HSGPA (Add SAT-CR + SAT-M + SAT-W) 0.54 0.62 0.08 SAT-CR + M (Add SAT-W) 0.51 0.53 0.02 HSGPA + SAT-CR + SAT-M (add SAT-W) 0.61 0.62 0.01 Predictors Note. Data from 2008 SAT Validity Study. Correlations corrected for restriction of range, pooled within-institution correlations Here is what the media might say: “The new SAT adds ONLY 0.08 over HSGPA - it is worthless!” “The new writing section adds ONLY 0.02 over SAT-CR & M – It’s not worth the extra time and cost!” 34 Switching who Sits in the Front Seat – Incremental Validity Example R1 R2 ΔR SAT-CR + SAT-M (Add HSGPA) 0.51 0.61 0.10 SAT-CR + SAT-M + SAT-W (Add HSGPA) 0.53 0.62 0.09 SAT-W (Add SAT-CR + M ) 0.51 0.53 0.02 SAT-W (add HSGPA + SAT-CR + SAT-M ) 0.51 0.62 0.11 Predictors Note. Data from 2008 SAT Validity Study. Correlations corrected for restriction of range, pooled within-institution correlations Here is what the media might say: “The HSGPA adds ONLY 0.09 over new SAT - it is worthless!” 35 “The SAT-CR & M add ONLY 0.02 over new writing section – why didn’t we always have a writing section!?” Straight-forward Approach: Increment of SAT controlling for HSGPA and Academic Intensity 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 76.6 50.7 29.8 800-1000 1010-1200 1210-1400 > 1400 13.9 CGPA >= 3.5 36 Bridgeman, Pollack, & Burton (2004) FYGPA Another way to think of a correlation of 0.53: Mean FYGPA by SAT Score Band SAT SCORE BAND 37 Using Course Grades as the Criterion rather than FYGPA • FYGPA is not always a reliable measure and it is difficult to compare across different college courses and instructors. • Sackett and Berry (2008) examined SAT validity at the individual course level. • Correlation of SAT and course grade composite = 0.58, compared to 0.51 for FYGPA. • SAT validity is reduced by 19% due to “noise” added as a result of differences in course choice. • HSGPA is not a stronger predictor than SAT when composite of individual course grades is used as criterion measure. 38 A Bumpy Road • The fairness issue: Standardized Differences, Differential Validity and Differential Prediction 39 Correlation of SAT scores & HSGPA w/ FYGPA by Race/Ethnicity Race/Ethnicity Subgroup American Indian Asian AfricanAmerican Hispanic White k (inst.) 16 82 83 86 109 N 384 14,109 10,096 10,486 104,017 SAT-CR 0.41 0.41 0.40 0.43 0.48 SAT-M 0.41 0.43 0.40 0.41 0.46 SAT-W 0.42 0.44 0.43 0.46 0.51 SAT 0.54 0.48 0.47 0.50 0.53 HSGPA 0.49 0.47 0.44 0.46 0.56 SAT, HSGPA 0.63 0.56 0.54 0.57 0.63 Previous research has shown tests and grades are slightly less effective in predicting performance of African American students. 40 Average Overprediction (-) and Underprediction (+) of FYGPA for SAT Scores and HSGPA by Ethnicity Race/Ethnicity American Indian Asian AfricanAmerican Hispanic White k (institutions) 103 109 108 110 110 n 798 14,296 10,304 10,659 104,024 SAT-CR -0.26 0.05 -0.30 -0.17 0.04 SAT-M -0.25 -0.07 -0.26 -0.16 0.05 SAT-W -0.22 0.04 -0.26 -0.16 0.04 SAT -0.22 0.01 -0.20 -0.11 0.03 HSGPA -0.25 0.02 -0.32 -0.27 0.06 SAT, HSGPA -0.20 0.02 -0.17 -0.12 0.03 Subgroup Also consistent with past research – The actual FGPA of under represented minorities average about .1 to .2 below predicted GPAs from SAT. HS grades consistently overpredict grades at a higher rate than tests. Over and underprediction are consistently reduced using both. 41 Validity research, in conclusion: • You get out what you put in – quality of data, data matching, institutional collaboration, the criterion problem • It is always easier to argue against something than propose an alternative (tests vs grades, tests vs nothing) • Selection – Using a predictor in selection (SAT, GRE, HS grades) will result in lower validity in proportion to the selectivity used. If you then compare the validity to a ‘new predictor’ not employed in selection it is not surprising to see higher correlations that will NOT stand up to operational validities. • For more information on CB research: http://collegeboard.com/research 42 Appendix Additional Materials Not Presented at Conference 43 Related Roadblocks • Addressing and disproving criticisms. An equal amount of effort spent collecting evidence for what the SAT does not do as is spent collecting evidence for what it does do. • Besides the criticisms described earlier (i.e.,SAT is a “wealth test”, provides no information over HSGPA), other criticisms as well as evidence to the contrary are presented. 44 “The SAT is to criticism as a halfback is to a football -- always on the receiving end.” Gose & Selingo (2001). The SAT's Greatest Test: Social, legal, and demographic forces threaten to dethrone the most widely used collegeentrance exam. Chronicle of Higher Education website. 45 SAT, at 3 Hours 45 Minutes, Draws Criticism Over Its Length (New York Times, December 16, 2005) • College Board Study: Investigating the Effect of New SAT Test Length on the Performance of Regular SAT Examinees (Wang, 2006) • Examined the average % of items answered correctly and the average number of items omitted for different sections of the test. • The average % items correct was consistent throughout the entire test, and the results were similar for gender, racial/ethnic, and language groups, and for different levels of ability as measured by total SAT score. • On average, students did not omit a larger number of items on later sections of the test. 46 • Conclusion: any fatigue that students may have felt did not impair their performance. SAT Essay Test Rewards Length and Ignores Errors (New York Times, May 4, 2005) • College Board Study: It is What You Say and (Sometimes) How You Say It: The Association Between Prompt Characteristics, Response Features, and SAT Essay Scores (Kobrin, Deng, & Shaw, submitted for publication) • A sample of SAT essay responses was coded on a variety of features regarding their length and content, and essay prompts were coded on their linguistic complexity and other characteristics. • The correlation of number of words and essay score was 0.62, which is smaller than that reported in the media. 47 SAT Coaching Raises Scores, Report Says (New York Times, December 18, 1991) • College Board sponsored study: Effects of Short-Term Coaching on Standardized Writing Tests (Hardison & Sackett, 2006) • Does coaching increase scores on the SAT essay? If so, does that coaching increase scores only on the specific essay, or does it also increase the test-taker’s actual writing ability that the test is intended to measure? • These results suggest that SAT essays may be susceptible to coaching, but score inflation may reflect at least some improvement in overall writing ability. 48 A Bumpy Road Continued: Fairness Issues 49 Previous findings… • Standardized differences • Males outperform females on Math and Critical Reading. • African-American and Hispanic students scored significantly lower than the total group on all academic measures • Differential Validity • • 50 SAT and HSGPA are more predictive of FYGPA for females and white students (larger correlations) Differential Prediction • SAT and HSGPA tend to underpredict FYGPA for females; however, the magnitude is larger for the SAT • SAT and HSGPA tend to overpredict FYGPA for minority students; however, the magnitude is larger for HSGPA Mean Academic Performance by Subgroups Subgroup Gender n SAT-CR SAT-M SAT-W HSGPA FYGPA Male 69,765 564 602 550 3.55 2.88 Female 81,551 557 559 557 3.65 3.05 798 544 555 529 3.52 2.77 Asian 14,296 562 624 562 3.66 3.05 African-American 10,304 506 503 498 3.39 2.63 Hispanic 10,659 524 537 520 3.59 2.73 No Response 6,738 587 590 576 3.63 3.05 Other 4,497 558 572 553 3.57 2.95 White 104,024 567 584 560 3.62 3.02 151,316 560 579 554 3.60 2.97 American Indian Race Total 51 Standardized Differences for 2006 Validity Study Variable Gender Race SAT-CR SAT-M SAT-W HSGPA FYGPA Female -0.08 -0.44 0.07 0.20 0.24 American Indian -0.17 -0.24 -0.26 -0.16 -0.28 Asian, Asian-American 0.02 0.47 0.08 0.12 0.11 African-American -0.56 -0.78 -0.59 -0.42 -0.48 Hispanic -0.38 -0.43 -0.36 -0.02 -0.34 No Response 0.28 0.12 0.23 0.06 0.11 Other -0.02 -0.07 0.00 -0.06 -0.03 White 0.08 0.05 0.07 0.04 0.07 Note. For gender, standardized difference was calculated as (Female Mean - Male Mean)/Total Standard Deviation. For race, standardized difference was calculated as (Subgroup Mean - Total Mean)/Total Standard Deviation. Negative values indicate lower performance than the referent group (i.e., males, total group). Positive values indicated higher performance than the referent group. 52 Correlation of SAT scores & HSGPA with FYGPA by Gender Gender Subgroup Male Female k (institutions) 107 110 N 69,765 81,551 SAT-CR 0.44 0.52 SAT-M 0.45 0.53 SAT-W 0.47 0.54 SAT 0.50 0.58 HSGPA 0.52 0.54 SAT, HSGPA 0.59 0.65 Note. HSGPA and SAT are stronger predictors for females . Research on many tests consistently demonstrates grades and tests are slightly better in predicting female performance than male performance in college. 53 Discrepancy between HSGPA and FYGPA Subgroup Gender Race Total 54 HSGPA FYGPA Median Mean HSGPA – Mean FYGPA Mean Median Mean Male 3.55 3.67 2.88 3.00 0.67 Female 3.65 3.67 3.05 3.17 0.60 American Indian 3.52 3.67 2.77 2.88 0.75 Asian 3.66 3.67 3.05 3.15 0.61 African-American 3.39 3.33 2.63 2.71 0.76 Hispanic 3.59 3.67 2.73 2.85 0.86 No Response 3.63 3.67 3.05 3.19 0.58 Other 3.57 3.67 2.95 3.08 0.62 White 3.62 3.67 3.02 3.13 0.60 3.60 3.67 2.97 3.09 0.63 Average Overprediction (-) & Underprediction (+) of FYGPA for SAT Scores & HSGPA by Gender Gender Subgroup Male Female k 107 110 n 69,765 81,551 SAT-CR -0.14 0.12 SAT-M -0.20 0.17 SAT-W -0.11 0.10 SAT -0.15 0.13 HSGPA -0.08 0.07 SAT, HSGPA -0.10 0.09 Predicted FGPA for males is .10 higher than actual GPA for males when SAT and HSGPA are used. Predicted FGPA for females that is .09 below actual FGPA. Consistent with past studies. 55 Other Avenues/Alternative Routes • Although our large-scale study is mostly concerned with predictive validity, we also have and will continue to collect other types of validity evidence that meets the recommendations of the Standards. 56 Evidence Based on the Consequences of Testing Writing Changes in the Nation’s K-12 Education System (Noeth & Kobrin, 2007) A College Board study to: • learn about changes in writing instruction across the nation’s K-12 education system over the past 3 years. • describe the near-term impact of the SAT writing section on K-12 education. 57 • Surveys were developed with items focused on changes in: attitudes and expectations, teaching, learning, and resources related to writing. • Surveys were administered via email to senior high school English/Language Arts teachers and school district administrators • The survey sample was carefully selected to represent the entire nation, with substantial representation of SAT states. • Nearly 5,000 teachers and 800 district administrators completed the writing surveys (9% and 7% response rates, respectively) 58 Selected Survey Results There has been much greater or slightly greater increase in: teacher attitudes about the importance of writing teacher expectations for writing performance class time spent on writing in ELA courses the focus of writing in the curriculum remedial writing programs the allocation of resources for writing the time devoted to grade writing assignments Teachers 77% 85% 80% 76% 39% 34% 7% Administrators 83% 91% 81% 81% 44% 55% 13% Percentage of teachers and administrators indicating writing as one of the most prominent parts or a very important part of the curriculum 59 Teachers Administrators Three Years Ago 37% 33% Today 61% 71% Selected Survey Results, cont. The SAT-Writing Section has been a major or minor factor in changing: writing priorities, attitudes & expectations the teaching of writing learning related to writing resources dedicated to writing overall importance placed on writing 60 Teachers 68% 62% 53% 33% 61% Administrators 57% 58% 53% 40% 55%