Open slides - CTN Dissemination Library

advertisement

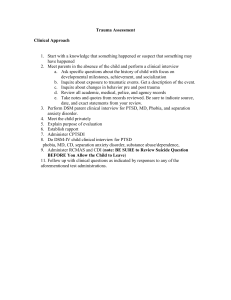

Integrated Treatment for Trauma and Addiction: Seeking Safety Denise Hien, PhD, LI Node, Columbia University Tracy Simpson, PhD, VAPSHCS, University of Washington NIDA CTN Blending Conference Seattle, WA October 16, 2006 PLEASE DO NOT CITE CONTENTS OF PRESENTATION WITHOUT PERMISSION OF THE AUTHOR Scope of the Problem 1 in 2 women in the U.S. experience some type of traumatic event (Kessler, 1995) Approximately 33% of females under age 18 experience sexual abuse (Finkelhor, 1994; Wyatt, 1999) Prevalence rates of PTSD in community samples have ranged from 13% to 36% (Breslau, 1991; Kilpatrick, 1987; Norris, 1992; Resnick, 1993) Studies have documented PTSD rates among substance using populations to be between 14%-60% (Brady, 2001; Donovan, 2001; Najavits, 1997; Triffleman, 2003) “The past isn’t dead, it isn’t even past.” -William Faulkner DSM-IV Criteria for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) A. Exposure to a traumatic event • Involved actual or threatened death or serious injury, or a threat to the physical integrity of self or others • Response involved intense fear, helplessness, or horror B. C. Event is persistently re-experienced Avoidance of stimuli associated with the event, numbing of general responsiveness D. Persistent symptoms of increased arousal • Difficulty falling or staying asleep, irritability or outbursts of anger, difficulty concentrating, hypervigilance, exaggerated startle response (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) Neurobiological Changes in Response to Traumatic Stress Limbic System -Hippocampus and Amygdala (Affect and Memory, e.g, Ledoux, 2000; van der Kolk, 1996) Neurotransmitters and Peptides (Numbing and Depression, e.g., Pitman, 1991, Southwick, 1999) Changes in Hormonal System (HPA axis) (Arousal, e.g., Yehuda, 2000) Pathways Between Trauma-related Disorders and Substance Use PTSD TRAUMA SUD Pandora The first woman, created by Hephaestus (God of Fire), endowed by the gods with all the graces and treacherously presented with a box in which were confined all the evils that could trouble mankind. As the gods had anticipated, Pandora opened the box, allowing the evils to escape. Clinical Challenges in the Treatment of Traumatic Stress and Addiction Abstinence may not resolve comorbid trauma-related disorders – for some PTSD may worsen Women with PTSD abuse the most severe substances and are vulnerable to relapse, as well as re-traumatization Confrontational approaches typical in addictions settings frequently exacerbate mood and anxiety disorders 12-Step Models often do not acknowledge the need for pharmacologic interventions Treatment programs do not often offer integrated treatments for Substance Use and PTSD Treatments for only one disorder—such as Exposure-Based Approaches are often marked by complications treatments developed for PTSD alone may not be advisable to treat women with addictions PTSD Treatment Approaches Cognitive Behavioral Prolonged Exposure: in vivo & imaginal; conditioning theory (Foa & Kozak, 1986; Cooper & Klum, 1989; Keane, 1991; Foa, 1991) SIT – Stress Inoculation Training (Foa, 1991) TREM – Trauma Recovery and Empowerment (Harris, 1998) STAIR – Skills Training in Affective and Interpersonal Regulation (Cloitre, 2002) EMDR – Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (Shapiro, 1995) PTSD/SUD Integrative Treatments Seeking Safety (Najavits, 1998) ATRIUM: Addictions and Trauma Recovery Integrated Model (Miller & Guidry, 2001) Not specifically designed for PTSD TARGET - Trauma Affect Regulation: Guidelines for Education and Therapy (Ford; www.ptsdfreedom.org) Comparison of Existing Trauma/ SUDFocused Treatment Research N Length of TX TX Content Follow Up Results Variable Limits Najavits, 1998 Triffleman, 2000 Brady, 2001 N=27 women 17 (>6 sess) N=19 (53% women) 39 (82% women) 15 (>10 sess) N=46 men No Control RCT No Control No Control Group, 24 sessions, 2x/wk, 90min/group Seeking Safety: Cog Behavioral Interpersonal coping skills Individual, 5 months, 2x/wk Individual, 16 sessions, 90 min sessions Exposure Therapy & CBT 12 weeks, 10 hrs/week partial hosp, CBT, RP & peer social support (2phase) Seeking Safety/CBT vs RPT 6 mo post 6/12 mo post 6/9 mo post Improvement in SU, PTSD & Depression Improvement in SU, PTSD SU, PTSD, Depression Small N, No Control, large drop out rate SU, PTSD Improvement @ 6 mo, diminished at 9 mo, no diff b/t SS/RPT SU, PTSD, Psych Nonrandomized TAU 3 mo post Improvement on SU, PTSD, Depression, increase in somatization SU, PTSD, Psych, Cog Small N, No Control, Did not follow up Drop-outs SDPT (Coping, CBT, Stress Inoc, In Vivo, RP-2 phase) vs 12 step 1 mo post Improvement on SU, PTSD, psych, No gender differences SU, PTSD, psych Small N, Short FU period Donovan, 2001 Small N, No Control, 30 day abstinence required, one site Hien, 2004 N=107 women RCT Individual, 3 months Women, Co-occurring Disorders & Violence Study (SAMHSA) Multi-site national trial (9 sites) examining implementation and effectiveness of treatment modalities for women with mental health, substance use and trauma histories Core Treatment Components Outreach and engagement Screening and assessment Treatment activities Parenting skills Resource coordination and advocacy Trauma-specific services Crisis intervention Peer-run services Spiral of Addiction and Recovery (Covington, 1999) “Do you think it is easy to change? Alas, it is very hard to change and be different. It means passing through the waters of oblivion.” -D. H. Lawrence, “Change” (1971) Motivational Enhancement for Patients with Comorbid PTSD & Substance Use Disorders Overview What is it like to be ambivalent? Why are motivation enhancement strategies promising ways to address these issues? Basic philosophy and components of MI MI example with a PTSD/SUD patient aMbivAlenCe Treatment Compliance A general study of missed psychiatric appointments (Portland VA) found that those with PTSD and/or a SUD were most likely to miss appointments Most studies of SUD treatment compliance have found that PTSD/SUD comorbidity is associated with poorer compliance Why do we see these patterns? Effects of Substance Use Patients with PTSD/SUD report stronger substance use expectancies for tension reduction Patients with PTSD/SUD report substance use helps to facilitate social situations get to sleep deal with bad dreams and trauma memories deal with negative emotions enhance positive emotions Other Challenges Social isolation/alienation/lack of trust in others Feelings of guilt or unworthiness Shrinkage of world Profound fear of own emotions and thoughts Sleep disturbance/nightmares Frightening re-experiencing symptoms Foreshortened sense of the future (why bother) Cognitive rigidity/poor attention capacities when stressed Numb and unable to tap into reinforcers Anger dyscontrol/irritability Trauma anniversaries during first month of treatment Disability/service connection issues (possibly) How might a motivational enhancement approach help those with PTSD/SUD comorbidity? PTSD Treatment Model Stages of Recovery (Herman, 1992) 1. SAFETY 2. MOURNING 3. RECONNECTION PTSD Treatment Model + MI Solidifying motivation to engage in safety work Safety and stabilization Integration and mourning Reclaiming or developing a meaningful life MI Enhances Treatment Engagement Among Other Dually Diagnosed Individuals Several studies have found that MIoriented session(s) ranging from 1 to 9 contacts have helped improve: Aftercare initiation Attending more treatment sessions Basic MI Principles Express empathy to convey understanding/acceptance Develop discrepancy between current and desired Avoid argument to limit resistance Roll with resistance and use it for momentum Support self-efficacy and belief that can change Basic MI Tools: OARS Open-ended questions; used to facilitate patient talking (yes/no ?’s can bog down) Affirmations; used judiciously and sincerely to convey warmth and appreciation Reflections; simple, double-sided, amplified, unstated emotions; used to facilitate further exploration Summaries; used to let patient hear their own words again and to convey understanding Opening Constructively or Balancing Concerns Ascertain patient’s understanding of session Explain role Orient to format and time Elicit patient’s central concerns Determine whether and how substance use is perceived to be a factor in concerns or problems, particularly with regard to PTSD symptoms Using Feedback Orient to feedback Provide normative information for comparison Use a neutral tone (nonjudgmental) Gently reflect back surprise, disbelief, concern Check whether information seems accurate Avoid argument; e.g., let disbelief go Include range of relevant information (not just drug and alcohol) Values Clarification or Developing Discrepancy Goal is to help patient articulate what he/she holds dear and ascertain how current behaviors may or may not be barriers to achieving what he/she wants in life Can use results of a values card sort to start conversation Tipping the Balance Towards Change Pros and Cons of NOT changing alcohol or drug use Pros and Cons of NOT changing PTSD-related behaviors (e.g., avoidance, anger behaviors) Pros and Cons of changing alcohol or drug use Pros and Cons of changing PTSDrelated behaviors Importance of making changes? How important to client is addressing her PTSD? How important is addressing her drinking? How important is addressing her marijuana use? 1 2 3 Not at all important 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Very important Confidence in ability to change? How confident is client that she can change her PTSD? How confident is she that she can change her drinking? How confident can change her marijuana use? 1 2 3 Not at all confident 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Very confident Menu of Options Once patient has indicated that she/he is willing to consider making a change: Elicit options patient is familiar with Ask permission to offer other options Provide information regarding other options Assist in sorting out viable option(s) Elicit statement regarding follow through Goals and how to get to them… Often useful to have written goal sheet that includes: Specific goal (or goals) First few steps to achieve goal(s) Reasons for making change List of who can be helpful and how Identify potential obstacles Identify ways of dealing with obstacles Important Feedback Mechanisms Your client’s in-session behavior is the central way to gauge whether you are dancing or wrestling Your own emotional or gut reactions to what is happening in the session are also critical for staying on track Listening to tapes of own sessions with or without rating Supervision (group or individual) opportunities to provide outside feedback and ideas as well as to get support for taking this quieter, gentler path How might Relapse Prevention help those with PTSD/SUD comorbidity? Seeking Safety (SS) vs. Relapse Prevention (RPT) vs. TAU Outcomes: PTSD Symptom Severity by Treatment Group (N=107) 0.5 0.2 -0.1 SS RPT TAU -0.4 **P<.01 **P<.01 End-of-Tx 3-month Post **P<.01 -0.7 -1 Baseline 6-month Post All analyses adjusted for age and baseline PTSD severity. End-of-Tx F=4.71 (2,106), r2=.42; 3-month Post F=4.94 (2,106), r2=.28; 6-month Post F=5.51 (2,106), r2=.22. Findings reported in Hien, DA, Cohen, LR, Litt, LC, Miele, GM & Capstick, C. (2004), Promising Empirically Supported Treatments for Women with Comorbid PTSD and SUD, American Journal of Psychiatry, 161:1426-1432. Do not cite without permission of the authors. Seeking Safety (SS) vs. Relapse Prevention (RPT) vs. TAU Outcomes: Substance Use Severity by Treatment Group (N=107) 0.5 0.2 -0.1 SS RPT TAU En d -o f-T x -0 . 0 6 0 .3 1 -0.4 -0.7 ***P<.00 1 **P<.01 End-of-Tx 3-month Post P=.06 -1 Baseline 6-month Post All analyses adjusted for age and baseline substance use severity. End-of-Tx F=6.01 (2,106), r2=.42; 3-month Post F=4.82(2,106), r2=.36; 6-month Post F=2.87(2,106), r2=.35. Findings reported in Hien, DA, Cohen, LR, Litt, LC, Miele, GM & Capstick, C. (2004), Promising Empirically Supported Treatments for Women with Comorbid PTSD and SUD, American Journal of Psychiatry. 161:1426-1432. Do not cite without permission of the authors. Relapse Prevention Treatment: Why does it work with PTSD? Symptoms of SUD and PTSD that overlap Emotion regulation problems that manifest in unstable temperament with expressions of anger, irritability, and depression Biased information processing and problem solving Difficulties with intimacy and trust Maladaptive emotion focused coping Emotion Regulation Deficits Difficulty managing anger Behavioral Impulsivity Affective lability Disruptions in attention, memory & consciousness Poor tolerance of negative emotional states Complex Trauma and Addictions: Underlying Commonalities Complex Trauma (DESNOS) is associated with repeated incidents (domestic violence or ongoing childhood abuse). Broader range of symptoms: self-harm, suicide, dissociation (“losing time”); problems with relationships, memory, sexuality, health, anger, shame, guilt, numbness, loss of faith and trust, feeling damaged. Self-Perpetuating Cycle Substance Use Interpersonal difficulties, no anger management, isolation Complicated Depression sleep disturbance & irritability Relapse Prevention Treatment Assumptions of RPT Substance abuse is a learned behavior A habit that can be changed Serves a function in their lives Positive consequences Negative consequences Abstinence or harm reduction is possible Difference motivation levels A lapse is not relapse G. A. Marlatt and J. R. Gordon (1985) Characteristics of RPT Active treatment for both clinician and client Focus on current emotional and substance abuse issues and their connection Identification of high risk situations Coping skills Triggers Cravings High risk situations Practice skills through homework Replace Addictive Behaviors Learn new coping skills Resisting social pressure Increase assertiveness Relaxation and stress management Communication skills Anger management Social skills Lifestyle Changes Increase pleasant activities Increase “positive addictions” and healthy habits Short-circuit “Seemingly Irrelevant Decisions” Seemingly Irrelevant Decisions Skill Rationale The most mundane choice can move you closer to using. You are not just an innocent bystander in your life. “It just happened….I couldn’t help it.” Promote accountability Creating Safety “Although the world is full of suffering, it is full also of the overcoming of it.” Helen Keller Seeking Safety Developed as a group treatment for PTSD/SUD women Based on CBT models of SUDs, PTSD treatment, women’s treatment and educational research Educates patients about PTSD and SUD’s and their interaction Goals include abstinence and decreased PTSD symptoms Focuses on enhancing coping skills, safety and self-care Active, structured treatment - therapist teaches, supports and encourages Case management Najavits, 2002; www.seekingsafety.org NIDA Clinical Trials Network Women & Trauma Sites Washington Node Residence XII Ohio Valley Node Maryhaven New England Node LMG Programs New York Node ARTC Long Island Node Lead Node South Carolina Node Charleston Center Florida Node Gateway Community Florida Node The Village Treatment Groups Seeking Safety (SS) Short term, manualized treatment Cognitive Behavioral Focused on addiction and trauma Women’s Health Education (WHE) Short term, manualized treatment Focused on understanding women’s health issues Support Participation in this study made possible by: NIDA CTN Long Island Regional Node NIDA/NIH Grant U10 DA13035 We would like to acknowledge all of the staff and participants who made this study possible. Participating Nodes and CTPs Node Node PI(s) Protocol PI CTP Site PI Location The Village Michael Miller Miami, FL Gateway Community Candace Hodgkins Jacksonville, FL Melissa Gordon LMG Programs Samuel Ball Stamford, CT Robert Sage Brooklyn, NY Florida Jose Szapocznik & Daniel Santisteban Lourdes SuarezMorales New England Kathleen Carroll New York John Rotrosen Marion Schwartz Addiction Research & Treatment Corporation Ohio Valley Gene Somoza Greg Brigham Maryhaven Greg Brigham Columbus, OH South Carolina Kathleen Brady Therese Killeen Charleston Center Mark Cowell Charleston, SC Washington Dennis Donovan & Betsy Wells Betsy Wells Residence XII Karen Canida Kirkland, WA Project Directors/Protocol PIs Frankie Kropp Agatha Kulaga Melissa Gordon Chanda Brown Silvia Mestre Nadja Schreiber Mary HatchMaillette Chris Neuenfeldt Cheri Hansen Karen Esposito Sharon Chambers CTN-0015 Research Staff Brianne O’Sullivan Ileana Graf Melissa Chu Nishi Kanukollu Treneane Salisbury Rebecca Krebs Ann Whetzel Stella Resko Carol Hutchinson Chanda Brown Janice Ayuda Pamela Bernard Jessica Ucha Nicole Moodie Allison KristmanValente Lynette Wright Melanie Spear Lisa Johnson Catherine Williams Calonie Gray Michele DiBono Rachel Hayon Barbara Bettini Barbara Thomas Lisa Markiewicz Elizabeth Cowper Rosaline King Lara Reichert CTN-0015 Clinicians Lisa Cohen Dawn Baird-Taylor Lisa Litt Martha Schmitz Karen Tozzi Darlene Franklin Kathleen Estlund Molly McHenry-Whalen Erin Demirjian Anslie Stark Karen Bowes Metris Batts Felisha Lyons Kathy McPherson Victoria Johnson Denese Lewis Sharon Anderson-Goss Merilee Perrine Angela Waldrop Leslie Lobel-Juba Maria Mercedes Giol Lourdes Barrios Lisa Mandelman Jeanette Suarez Danielle Macri Maria Hurtado Tina Klem Nancy Magnetti Anne Marie Sales Renee Sumpter Michelle Melendez Ida Landers Regina Morrison Clare Tyson Mary Hodge-Moen Sandra Free Goldie Galloway Karen Canida Katie Revenaugh CTN-0015 QA and Data Management Jim Robinson JP Noonan Connie Klein Karen Loncto Chris Hutz Lauren Fine Michelle Cordner Melissa Gordon Maura Weber Kristie Smith Catherine Dillon Donna Bargoil Jurine Lewis Girish Gurnani Inna Logvinsky Peggy Somoza Sharon Pickrel Katie Weaver Molly Carney Catherine Otto Rebecca Defevers Emily DeGarmo Royce Sampson Stephanie Gentilin Clare Tyson Anthony Floyd Nathilee Francois