FWS_BLM Lecture_2007

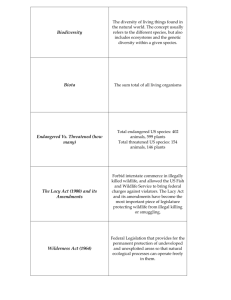

advertisement

Bureau of Land Management • Manages 264 million acres • Mostly arid lands in the west although some very productive, and biologically important forestlands • Arid lands also important! Desert ecosystems, shrub steppe, tall grass and short grass prairies, riparian ecosystems, etc. – Some habitat types have become exceedingly rare; others are highly impacted by grazing – Report: Endangered Ecosystems of the U.S. by Reed Noss (1995) • Less than 1% of native prairies left • 90% of remaining shrub-steppe severely impacted by grazing • 30% of arid and semi-arid lands have been severely desertified and 60% slightly desertified – Riparian management on BLM lands is a major issue – Exotic species invasion on rangelands also a major issue Bureau of Land Management • Very different history from USFS or NPS – Lands not from reserves, but what was left over. • As settlers moved west, water became scare – Farming shifted to grazing, rangers needed more grazing land – so federal lands became grazing commons – Resulted in large problem of over grazing • Taylor Grazing Act 1934 (amended 1939) – Set up gazing districts with advisory boards – Established fee for grazing on fed lands • 1946 Truman reorganization plan – created BLM – Responsible for grazing districts and mineral leasing – Decentralized – more and more a “captive” agency – Tried to consider multiple use, but no specific authority Federal Lands Protection and Management Act • • 1976 Organic Act for the BLM – similar to the U.S. Forest Service’s NFMA FLPMA is called the BLM Organic Act because it consolidated and articulated BLM's management responsibilities. Many land and resource management authorities were established, amended, or repealed by FLPMA, including provisions on Federal land withdrawals, land acquisitions and exchanges, rights-ofway, advisory groups, range management, and the general organization and administration of BLM and the public lands. FLPMA also established BLM as a multiple-use agency — meaning that management would be accomplished on the basis of multiple use and sustained yield unless otherwise specified by law — and provided that: . . . the national interest will be best realized if the public lands and their resources are periodically and systematically inventoried and their present and future use is projected through a land use planning process coordinated with other Federal and State planning efforts . . . FLPMA also specified that the United States receive fair market value for the use of the public lands and their resources unless otherwise provided for by statute, and that: . . . the public lands be managed in a manner that will protect the quality of scientific, scenic, historical, ecological, environmental, air and atmospheric, water resource, and archeological values; that, where appropriate, will preserve and protect certain public lands in their natural condition; that will provide food and habitat for fish and wildlife and domestic animals; and that will provide for outdoor recreation and human occupancy and use . . . In short, FLPMA proclaimed multiple use, sustained yield, and environmental protection as the guiding principles for public land management. Thanks to FLPMA, BLM manages public lands so that they are utilized in the combination that will best meet the present and future needs of the American people for renewable and non-renewable natural resources. BLM lands today • • • • • • More and more attractive as recreational lands Wilderness Study Areas ORV use huge! Also non-motorized recreation >60 million visitor days per year Leading to conflicts with traditional uses BLM now conducting planning under new ecosystem management guidelines. • BLM is trying to manage for ecosystem integrity, but faces legal and political challenges to this approach. e.g. Nye county in Nevada. U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service • Evolution of management philosophy: – Emphasis shifted from migratory birds to Endangered species to whole ecosystems • How does this compare to the evolution of thinking within the U.S. Forest Service and the National Park Service? Controversy over who should regulate fish and wildlife – states or federal government – began in the 19th century and has continued to this day. Outcome: resident fish and wildlife – property of state Migratory fish and wildlife – property of federal government Endangered species – regulated differently following the ESA • Need to protect wildlife came from rampant market hunting during the mid to late 19th century – Extinction of passenger pigeon – Severe declines in bison, beaver, deer, elk, turkey, water fowl, wading birds – No bag limits – Sportsman’s groups active in protection – State’s started passing laws • 1900 Lacey Act – prohibits interstate transport of game killed in violation of state law. • States began to limit fishing in inland waters also How could the fed. gov. regulate fish and wildlife? 1. Could ban hunting on its land (e.g. Yellowstone NP in 1894) 2. Responsible for migratory fish and wildlife – could regulate interstate commerce 3. Could establish federal refuges – first refuges established under the Antiquities Act of 1906 • National Bison Range 1908 • National Elk Range 1912 Early, but important, statutes • • • • Migratory Bird Act 1913 – Federal treaty making powers to conserve migratory waterfowl – Few explicit powers though Migratory Bird Conservation Act – U.S. Dept. of the Interior to purchase lands to refuges – Wetland conservation Migratory Bird Hunting Stamp Act 1934 – Hunters required to purchase “duck stamps” – Funds dedicated to purchase migratory bird habitat – about 2 million acres purchased under this program Fish and Wildlife Coordination Act 1934 – Federal responsibility for evaluating effects of federal projects on fish and wildlife or its habitat National Refuge System • 1966 National Refuge System Administration Act – More refuges – Combined game refuges, wildlife refuges, waterfowl sanctuaries and management areas into one National Wildlife Refuge System – Unlike the Organic Acts for FS, BLM, or PS, it did not specify objectives for system • Each refuge has its own mandates • Lots of uses “grand fathered” in – Called “compatible uses”: agriculture, livestock grazing, recreation, timber harvest, mining – No guidance on how to balance uses Silvio Conte Today: •93,604,626 acres in the National Wildlife Refuge System •86% of the lands are in Alaska •560 units •32,700 acres in Vermont plus Nulhegan •5,800 in New Hampshire •28,400 in New York •54,600 in Maine Previous FWS management objectives 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. Perpetuality of migratory bird resources Preserving natural diversity: flora and fauna on refuges Preserving, restoring, and enhancing endangered and threatened species Providing refuge visitors with opportunities to learn about fish and wildlife ecology Providing wildlife-oriented recreation experiences New, additional FWS management objectives • • • • • • • • perpetuation of natural communities of plants and animals; maintenance of naturally-occurring structural and genetic diversity; needs of rare and ecologically important species; minimization of habitat fragmentation; maintenance of uncontaminated land and water; continued role of natural processes (e.g., fire, floods); control of undesirable exotic species; and maintenance of compatible, sustainable human activities. So major shirt to ecosystems as focus for management Endangered Species Act • Previous legislation: – 1966 – called for listing and saving endangered wildlife – Reflected growing awareness of species loss: since 1500s, and estimated 500 species had disappeared in the U.S. – Environmental movement called for shift away from the preoccupation with game species – challenged the “captive agency” approach • ESA passed in 1973 (amended in 1978) Key provisions: 1. Put responsibility for endangered species in hands of federal government 2. Set up a process for study of candidate species and subsequent listing as threatened or endangered 3. All federal agencies required to conserve and restore listed species 4. Emphasized habitat protection: designation of critical habitat Threatened = Any species or subspecies that is likely to become endangered within the foreseeable future throughout all or a significant portion of its range Endangered = Any species or subspecies that is in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range “Take” “Take”= killing, harming, or harassing. Courts have defined this to include habitat destruction Has the ESA worked? Success stories: gray whale, bald eagle, perhaps wolves Often highly contentious: e.g. grizzlies Positive aspects of the ESA 1. ESA is the only legislation protecting imperiled species and habitats; Canada does not even have one! 2. ESA is clear and concise; goals are achievable 3. Act is flexible 4. ESA is good example for rest of the world 5. Act protects an important public resource 6. Despite act, 12 species have gone extinct. Many more would have without the ESA. 7. 1973 – 109 listed species; 1995 - >900 listed species in US.; >500 international species But 3,700 candidate species Original list mostly vertebrates; now adding mostly invertebrates and plants Criticisms of the ESA 1. Emergency room conservation 2. Ecosystem-level habitat protection better 3. Lack of clearly defined thresholds for listing 4. How to define a viable population 5. Metapopulations not adequately protected 6. Habitat reserves not protected adequately to sustain “recovered” populations 7. FWS discounts uncertainty and long-term threats Perhaps we need an “Endangered Ecosystems Act” Habitat Conservation Plans – an increasingly used tool allowed under the ESA - Long-term landowner certainty in exchange for habitat conservation standards Negotiated with the FWS National Environmental Policy Act • Passed in 1969, Amended in 1970 OFTEN DRIVES HOW ECOSYSTEM MANAGEMENT PROJECTS ARE DONE NEPA Key Provisions • Created CEQ – Council on Environmental Quality • Requires EA or EIS for federal actions – Environmental Assessment (EA) – Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) Environmental Assessment • More concise -- for actions of more limited scope – must include a discussion of the proposal, alternatives, and environmental impacts of both • EA is followed by one of two conclusions: 1.Finding of No Significant Impact (FONSI) with supporting presentation of reasons why no impact expected 2.Decision to prepare an EIS Environmental Impact Statement • Intent – – to provide full and fair discussion of significant environmental impacts to inform decision makers and the public of the reasonable alternatives • Process – – – – NOI – Notice of Intent Scoping Draft EIS, Final EIS ROD – Record of Decision A New Policy and Legal Framework for Ecosystem Management Does our current legal and administrative framework facilitate ecosystem management? Management functions are separated in different agencies: • • • U.S. Forest Service – Responsible for forests, wildlife on national forests Fish and Wildlife Service – Responsible (with the States) for biodiversity (plants, wildlife, etc.); plants and animals depend on clean air and water …but… U.S. Environmental Protection Agency – responsible for clean air and water, also hazardous and solid waste regulation Federal agencies driven by their authorizing legislation: • Statutes not written with interagency cooperation in mind • Ecosystem management requires cooperation • Individual agencies view desired ecosystem conditions narrowly – within the context of their mandates • Traditionally, agencies have not had interdisciplinary expertise, although that is changing Ecosystem management now a core responsibility under new agency policies What should the agencies do differently? • Must work within ecosystem boundaries, not administrative boundaries • Cross-agency management – comprehensive management of ecosystems involving all levels of government and the public • Public involvement adapt to changing societal expectations and values • Work proactively!!! Examples of inter-agency cooperation and comprehensive management Northern Forest Lands Study: • Governors of 4 states • U.S. Forest Service • Industry • Environmental Groups • Local government Chesapeake Bay Program • Initiated by federal legislation • 7 States • Key federal agencies Northwest Forest Plan • U.S. Forest Service • Bureau of Land Management • Additional involvement by U.S. EPA, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, and National Park Service Interior Columbia Basin Ecosystem Management Project: Federally Owned Lands within the Assessment Area National Estuary Program and Coastal Zone Management U.S. EPA National Oceans and Atmospheric Agency (NOAA) State agencies Citizen groups