Ed Lonnon`s Endangered Species Homepage

advertisement

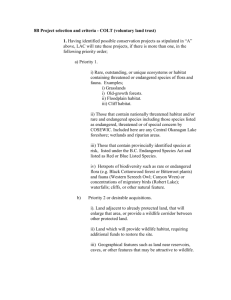

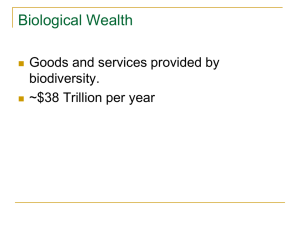

THE AUSTRALIAN SITUATION Ed Lonnon’s Endangered Species Homepage http://home.swiftdsl.com.au/~endangered/discuss.htm More than thirty percent of all recorded mammal extinctions in Australia occurred between about 1800 and the present. It is generally accepted that 20 species are extinct and many more greatly reduced in numbers and range, sometimes with only tiny surviving populations. Mammals have been chosen for the purposes of illustration in this note because of the severity of the situation with these taxa. It must be pointed out, however, that there are similar problems with some species of all other vertebrate taxa of Australian fauna. There are, of course similar issues of preservation and conservation of invertebrate fauna, and this fauna is a most important component of the total biodiversity of Australia because of the huge number of species involved, relative to vertebrates. The precise causes of the extinction of most Australian mammal species is open to some debate. Europeans brought many changes to the country including new species which were competitive with or predatory upon the native wildlife. In recent years, through the use of modern radio-tracking equipment on captive bred animals of threatened species released into the wild, it has become clear that introduced predators, and particularly foxes, are capable of wiping out a small group of a susceptible species in a matter of a few weeks. Effective methods of predator control over most of the continent are imperative if endangered species are to survive in the wild. This is proving to be a difficult problem. The Australian wildlife conservation agencies, the IUCN and the statutory zoos have been working in collaboration to develop "action plans" for the preservation / conservation of rare and endangered native fauna. These plans involve relocating selected species to facilities in which they can be kept in open range but captive conditions, free of exotic predators, introduced diseases and competitors, where they can increase in numbers under careful management and be the subjects of sound studies, the results of which can assist in their long term future. The decline in biodiversity in Australia is serious. Because the country was first occupied by Europeans in only 1788, and the biota was subject to relatively intense scientific study during the past two centuries, the decline is well documented. The most severely depleted taxa are mammals in the weight range of 35-5500 grams. Many of these species have lost more than 80% of their original ranges and most are extinct in the semi-arid and arid parts of the mainland. Habitat loss and introduced predators and competitors have been the major threats to these animals. About 14.4 percent of Australia's known 15,638 vascular plants are listed as threatened by IUCN. LOSS OF WILDLIFE HABITAT On a global basis, habitat destruction is the cause of most extinctions. Loss of terrestrial wildlife habitat is massive and is increasing. Tropical moist forests in particular have been, or are being, greatly impacted. These forests support an extraordinarily diverse biota and are being cleared at a very rapid rate. Citing several IUCN and United Nations sources, McNeely et al (1990) acknowledged the lack of precision in the estimates of contemporary rates of clearing of such forests, but conclude that this rate is likely to be at or above 0.6% per year. They further concluded that about 65% of wildlife habitats in Sub-Saharan Africa and Tropical Asia had been lost by 1990. These levels are clearly not sustainable. Their impacts are not only on biodiversity, but also on global climate, rates of soil loss, fresh-water and marine pollution and ultimately on the capacity of the planet to produce food, fibre and fuel for humans. THE IMPACT OF THE HUMAN POPULATION The increase in recent extinction rates is related to human population size and the exploitation of natural resources. The rate of human population growth has been extraordinary. It has been estimated that, in 1 AD, the global human population was about 150 million, concentrated on the coastal fringes ofEast Asia, India and the Mediterranean. The population did not double to 300 million until 1350, but by 1950 there were 2.4 billion and in 1985 there were 5 billion (Tanton 1994). This population and its activities has had dramatic impacts on biodiversity and natural ecosystems. Diamond (1992), indicated some of the more dramatic ecological impacts of a large and increasing population size: "At present, humans are commandeering 40 percent of all the biological energy fixed from sunlight on the planet, either by eating, clearing the land, or grazing their animals on it. The human population is doubling every 40 years, so in 40 years from now - 2032 -we will be commandeering nearly 80 percent of all the energy from sunlight that is fixed by biological systems. By 2050 we will be using 100 percent, and we will be fighting each other in dead earnest. " The assumptions implicit in the statement above are rather broad and open to challenge, specifically in relation to timeframe. In reality, this does not matter much - we humans are consuming the resources on which we depend at rates which are unsustainable in the medium term and those rates are increasing as the global population grows and strives for a better material quality of life. Recent trends in wildlife extinctions are valuable examples of what could happen to humans and which could happen rapidly and soon. Species at the highest trophic levels in an ecosystem are those most severely affected by breakdown of the ecological processes that drive the system. Humans are right at the top of a very complex suite of ecosystems, many of which have been greatly changed. One of the few physical type principles in ecology is that a stable ecosystem displaced from stability will oscillate violently until it finds a new stability. Because of the complexity of ecosystems and their driving processes, the nature of new equilibria are very difficult to predict, as are the losses sustained along the way from the old to the new stabilities. I would not like to see humankind go into a dramatic decline, with all the strife and suffering that will attend such a decline, because of failure to heed the obvious lessons of the past and the physical, sociological and ecological knowledge now available. We are, however, heading inexorably in that direction.