RHETORIC

advertisement

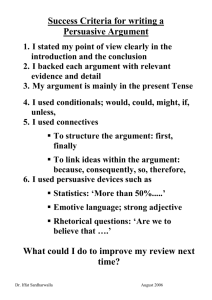

RHETORIC I • Rhetoric = df. 1. (M&P) Language used primarily to persuade or influence beliefs or attitudes rather than to prove something logically. 2. The art of speaking or writing effectively. • Rhetoric usually works through the emotive, or rhetorical force of words and phrases – the emotional associations they express and elicit. – For instance, saying that someone did not play a part in a play very well is not nearly as strong as saying that he butchered the role. • Rhetoric relies on an additional or alternative meaning in a statement [given by a particular word or phrase in the statement] to give the statement a certain spin. RHETORIC II • Rhetoric is a device by which a speaker or a writer can influence the beliefs or attitudes we have about something. • For critical thinking, rhetoric is not a substitute for argument. Thus substituting rhetoric for argument is a mistake in critical thinking. – Saying that someone ‘butchered’ a role is not an explanation of what made the performance a bad one, or calling abortion ‘baby murder’ is not in itself an argument against the morality of abortion. • People are sometimes more persuaded by rhetoric than reasoning, but they shouldn’t be. RHETORIC III • Rhetoric may be psychologically powerful, but by itself it establishes nothing. • To be persuaded by rhetoric alone is not to think critically. • Rhetoric is sometimes used in place of argument, and sometimes used in argument, as in many political speeches. • It is important to understand that the logical force or correctness of an argument is one thing, and its rhetorical force or power to persuade is another. • Rhetoric does not in itself have anything to do with the logical correctness of an argument. • However, this does not mean that the use of rhetoric in an argument makes the argument weaker, just that it does not make it stronger logically, but perhaps only more persuasive psychologically. RHETORICAL DEVICES • A rhetorical device =df. Something used to influence belief or attitude through the associations, connotations, or implications of words, sentences, or paragraphs. • A rhetorical device can make an argument more persuasive psychologically, but does nothing to add to or detract from the logical worth of an argument. • Rhetorical devices are not necessarily bad, it is just that, in themselves, they give us neither a reason to accept nor a reason to reject an argument. (See the example in the box on page 126.) • Rhetorical devices can be called ‘slanters,’ since they are designed to give a claim a positive or negative slant regarding a subject. EUPHEMISMS AND DSYPHEMISMS I • A euphemism =df. A word or expression which is neutral or positive and which is used in place of a negative word or expression. (‘Euphemism’ literally means ‘sounding good.’) – ‘Bathroom’ is a euphemism for ‘place containing a plumbing receptacle for urination,’ and ‘passed away’ is a euphemism for ‘died.’ • Euphemisms play an important role in affecting our attitudes. – ‘Capital punishment’ sounds better than ‘killing by the state,’ and ‘voluntary termination of pregnancy’ sounds better than ‘baby murder,’ or perhaps even ‘abortion.’ EUPHEMISMS AND DSYPHEMISMS II • A dysphemism =df. A word or expression which either produces a negative effect on the attitude of a reader or listener regarding something, or lessens positive associations concerning that thing. (‘Dysphemism’ literally means ‘sounding bad.’) – ‘Croaked’ is a dysphemism for ‘died,’ and ‘baby murder’ is a dysphemism for ‘abortion.’ • The use of euphemisms and dysphemisms can be deceptive, and are so when they are designed to lead in one way or another apart from the logic of the argument. – Thus both the use of ‘right to choose’ and ‘killing of the innocent’ tend to slant argument about abortion in one way or another, when attention should be paid to the logical force of any argument on this issue. EUPHEMISMS AND DSYPHEMISMS III • Even though euphemisms and dysphemisms can interfere with argument, they can at times be useful and appropriate. – A euphemism can enable us to treat a sensitive subject like death appropriately for someone whose spouse has just died. – Note, however, that calling genocide ‘ethnic cleansing’ seems inappropriate for the egregiousness of the crime. • In addition, some facts of life are “repellent, and for that reason neutral reports of them sound horrible.” – For instance, trying to report what happened on 9/11 in a neutral way would seem improper given the nature of that action and thus might be seen by some as dysphemistic. • However, neutral reports of unpleasant, evil, or repellant facts do not automatically count as dysphemistic rhetoric. TECHNIQUES OF PERSUASION • A persuasive comparison = df. One which is used to express or influence attitudes or affect behavior. “John is as big as a barn” persuades the hearer that John is larger than normal by comparing him to a building. • A persuasive definition =df. One in which the definiens contains a term or terms which are prejudicial, and so evokes an attitude about the definiendum. – Defining ‘abortion’ as ‘baby murder’ is an example of a persuasive definition. – Also, in the definiens a fetus is assumed to be a human being. – Since this is something to be proved, not assumed, the definition also begs the question of the morality of abortion. • A persuasive explanation =df. An explanation intended to influence attitudes or affect behavior. – Saying that people are conservative politically when they have a lot of money is a persuasive explanation of the voting habits of some people. STEREOTYPES • A stereotype =df. A thought or image about a group of people, animals or things based on little or no evidence. • Saying that people from group x are stingy, that animals from group y are stupid, and that things from group z are inferior to things from another group, when based on little or no evidence, are stereotypes. • Stereotypes are often based on group or individual interests. • A stereotype is an oversimplified generalization about the members of a certain class of people or things. • Language that reduces people or things to categories can induce an audience to accept a claim unthinkingly or to make snap judgements concerning things which they know little about. INNUENDO • Innuendo =df. A form of suggestion in which something negative is insinuated about someone or something rather than actually said. – For instance, a professor says to his students: “You can be sure that, with me, there is at least one instructor at this university that always observes fair-grading practices.” – This is innuendo because it is suggested that some university instructors do not always grade fairly. – Even though the statement is logically consistent with its being the case that everyone grades fairly, the idea is suggested that unfair grading sometimes occurs on campus. • Condemning someone with faint praise is a form of innuendo. – “I’m pleasantly surprised at how well you’ve done in this class.” is not literally negative, but is so suggestively. LOADED QUESTIONS • Every question rests on an assumption. – For instance, asking: “Are you hungry?” assumes that you are the sort of being that needs to be fed, that you can understand the question, and that you are in a position to answer it. • A loaded question =df. A question which rests on one or more unwarranted or unjustified assumptions. – “Do you still cheat on exams?” is a loaded question if the student of whom it is asked has never cheated. – The question rests on the assumption that the student has cheated in the past. – If that is untrue, then the assumption is unwarranted, and so the question is loaded. • The loaded question is technically a form of innuendo, because it permits us to insinuate the assumption that underlies a question without coming right out and stating that assumption. WEASLERS • A weasler =df. An expression used to protect a claim from criticism by weakening it. • Words such as ‘perhaps,’ ‘possibly,’ ‘maybe,’ and ‘may be’ are examples of words which can be used in weaslers, since they can be used to produce innuendo, to plant a suggestion without actually making a claim that a person can be held to. – The word “perhaps” in “Perhaps John cheated on the last test” is there used as a weasler. – It creates innuendo by suggesting that John did something wrong. – But it does not actually claim wrongdoing, and is thus consistent with John’s not cheating. • Words used to weasel can also be used legitimately; saying “Jane may be the best student in the class” is not weaseling. DOWNPLAYERS I • Downplaying =df. An attempt to make someone or something look less important or significant. • Stereotypes, persuasive comparisons, persuasive explanations, and innuendo can all be used to downplay something. • Downplayer =df. A word or expression used to play down or diminish the importance of a claim. – “She’s only published a single work.” Here the downplayer is “only,” and the implication is that she can’t be very significant a thinker or writer with one work to her credit. Or “He’s a so-called thinker.” • Quotation marks can be used to downplay the significance of something. – “John’s ‘education’ came from a correspondence school.” DOWNPLAYERS II • Conjunctions such as ‘but,’ ‘however,’ and ‘nevertheless,’ can be used as downplayers. – “Yes, she wrote a brilliant book, but look at how long it took her to do it.” • The context of a claim can determine whether it downplays or not. – Example: “Long only won by six votes.” • Slanters [linguistic devices used to affect opinions, attitudes, and behavior without argumentation] really can’t – and shouldn’t – be avoided altogether. – They can give our writing flair and interest. – What can be avoided is being unduly swayed by slanters. HORSE LAUGH • Horse laugh is ridicule of all kinds, and includes use of sarcastic language or laughing at a claim made. • Ridicule is not reasoning, and in horse laugh, ridicule is used to reject a claim. • Example: “You call that art? Ha, ha, ha, ha, ha!” • In sarcasm a sharp remark - which is often ironic or satirical - is used intentionally to cause pain. (Irony is the use of words to express something other than, and especially the opposite of, literal meaning.) – For instance, Oscar Wilde once asked James Whistler’s opinion of a poem which Wilde had written. Whistler read it, handed it back to Wilde and said, “It’s worth its weight in gold.” Wilde never forgave him. HYPERBOLE I • Hyperbole = df. Extravagant overstatement; obvious exaggeration for effect; an extravagant statement not intended to be understood literally. Hence hyperbolic = df. Having the nature of hyperbole; exaggerated. – For instance, saying “Jane has the brain of ten people put together” is a hyperbolic way of saying that Jane is very intelligent. – Saying “I am dying of hunger” when it has only been six hours since you have eaten is hyperbole. • Not all strong language is hyperbole. – Saying “Jane is the best student in the class, and may be the best student I have ever had” is strong language but is not hyperbolic. – Saying “Jane is the best student anywhere” is. HYPERBOLE II • Both persuasive comparisons and dysphemisms can involve hyperbole. – If we said “If he were just a little smarter he could compete intellectually with the average vegetable” is a hyperbolic persuasive comparison (as well as an example of ridicule or horse laugh.) – Calling a professor a ‘fascist’ because she expects you to be in class on time is a hyperbolic dysphemism. • But a claim can be hyperbolic without containing excessively emotive words or phrases.” – For instance, saying “Jane is the best student anywhere” is hyperbolic but unemotional. • It’s when the colorfulness of language becomes excessive – a matter of judgement – that the claim is likely to turn into hyperbole. HYPERBOLE III • Hyperbole is a kind of slanting device which can be used to slant in a positive or negative direction. • Hyperbole can have a psychological effect on the listener or reader since, even if you reject the exaggeration, you may be moved [perhaps unconsciously] in the direction of the basic claim. – For instance, even if you recognize “Jane is the best student anywhere” to be hyperbole, still you may now think that Jane must be incredibly bright for anyone to make that statement. • One must be careful about hyperbole; it can add a persuasive edge to a claim that it doesn’t deserve. PROOF SURROGATES I • Proof surrogate =df. An expression used to suggest that there is evidence or authority for a claim without actually citing such evidence or authority. • A surrogate is a substitute, or one thing which stands in place of another, and here an unsupported claim stands in place of proof. – For instance, saying “Experts say that . . .” without saying who the experts are and how it is known that what they say is true is an example of proof surrogate. – Another example is “studies show . . .” without specifying which studies, and who did them, and according to what standards they were conducted. – Or, “it is obvious that . . .” when it is not obvious at all. PROOF SURROGATES II • Proof surrogates are just that – surrogates. They are not real proof or evidence. • Saying “There is every reason to believe that students at IPFW want [such and such]” is proof surrogate unless the assertion of belief is supported by proof or good evidence. • Such proof or evidence may exist, but until it has been presented, the claim at issue remains unsupported. • At best, proof surrogates suggest sloppy research; at worst, they suggest propaganda. ADVERTISING I • Advertising serves a variety of purposes: – The majority of advertising is aimed at getting people to buy things, such as soap, cars, or coffee. – Other ads try to get us to use something, e.g., a credit card. – Still others try to get us to do something, like vote for a candidate or join an organization or give to a charity. • They have in common the aim of getting people to perform a particular action or set of actions, with the suggestion that either the person who performs the action or the world in general will be improved as a result of the action. • Since the only good reason to buy anything is if it will improve our lives, we should buy something based on an ad for that thing only if the ad establishes that we would be better off with the product than without it. ADVERTISING II • Rhetorical devices are frequently used in advertising. • Remember that rhetorical devices are things which are used to influence belief or attitude through the associations, connotations, or implications of words, sentences, or paragraphs. • Advertising firms understand our fears and desires at least as well as we understand them ourselves, and they have at their disposal the expertise to exploit them. ADVERTISING III • There are two basic kinds of ad: 1. Those that offer reasons for buying something or for doing something 2. Those which do not. • There are three kinds of ad which do not offer reasons for buying the product advertised: 1. Those which result in pleasurable feelings in us, for instance by making us laugh, 2. Those which use people we admire or who we think are like us in some way or ways, for instance a celebrity or an ordinary consumer. 3. Those which use situations in which we would like to be, for instance on vacation in Tahiti - Some ads can combine all or some of these. ADVERTISING IV • To buy a product based on a reasonless ad is not justified on principles of critical thinking. • It is not reasonable, unless you already know that you want the product and can afford it, and the ad merely tells you that the product you want is available and where you can get it. • The claims of advertisers are notorious for not only being vague, but for also being ambiguous, misleading, exaggerated, and sometimes plain false. • Because of this, we should be suspicious in general about claims made by advertisements, and should seek information about the product advertised which goes beyond the ad itself. ADVERTISING V • Further, we are not justified in buying something based on an ad for that thing alone. • This is true even if the ad is an honest description of the thing being advertised, because we cannot tell from the ad alone that that is the case. • Even advertisements that present reasons for buying an item do not by themselves justify our purchase of the item. • Our suspicions about advertising in general should undercut our willingness to believe in the honesty of any particular advertisement. SUMMARY I • Winning acceptance for a claim without presenting reasons for the claim M&P call rhetoric. • Rhetorical devices are “words or phrases that have positive or negative emotional associations, suggest favorable or unfavorable images, or manipulate the assumptions and expectations that always underlie communication.” • Advertising uses rhetorical devices, and largely concerns nonargumentative persuasion, and so should be approached critically. SUMMARY II • Common rhetorical devices: 1. Euphemism – An agreeable or inoffensive expression that is substituted for an expression that may offend the hearer or suggest something unpleasant. 2. Dysphemism – A word of phrase used to produce a negative effect on a reader’s or listener’s attitude about something or to tone down the positive associations the thing may have. 3. Persuasive comparison – A comparison used to express or influence attitudes or affect behavior. 4. Persuasive definition – a definition used to convey or evoke an attitude about the defined term and its denotation. SUMMARY III • Common rhetorical devices (continued): 5. Persuasive explanation – An explanation intended to influence attitudes or affect behavior. 6. Stereotype – An oversimplified generalization about the members of a class. 7. Innuendo – An insinuation of something deprecatory. 8. Loaded question – A question that rests on one or more unwarranted or unjustified assumptions. 9. Weasler – An expression used to protect a claim from criticism by weakening it. SUMMARY IV • Common rhetorical devices (continued): 10. Downplayer – An expression used to play down or diminish the importance of a claim. 11. Horselaugh – A pattern of pseudoreasoning in which ridicule is disguised as a reason for rejecting a claim. 12. Hyperbole – Extravagant overstatement. 13. Proof surrogates – An expression used to suggest that there is evidence or authority for a claim without actually saying that there is.