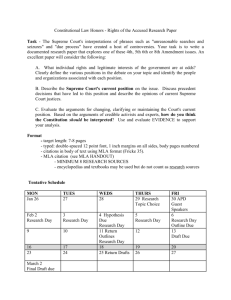

Fourth Amendment - SpartanDebateInstitute

advertisement