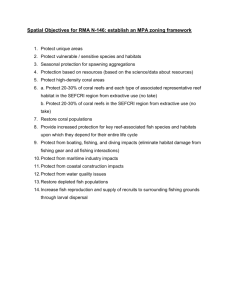

OL OOP Section 05 - Central Caribbean Marine Institute

advertisement

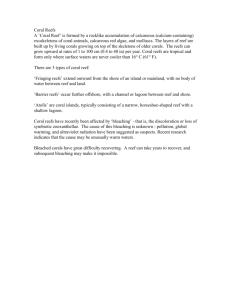

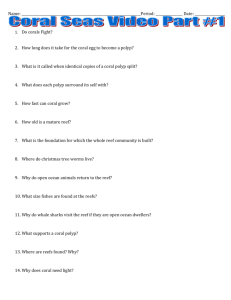

0 OUR OCEAN PLANET OUR OCEAN PLANET SECTION 5 – TROPICAL SEAS 1 REVISION HISTORY Date Version Revised By Description Aug 25, 2010 0.0 VL Original 5. TROPICAL SEAS 5. TROPICAL SEAS 2 5. TROPICAL SEAS Tropical seas are warm, clear, sunlit seas that girdle the Equator between the Tropic of Cancer and Tropic of Capricorn. Several key habitats are found in tropical seas, namely: 1. Mangroves The mangrove habitat plays an important role in tropical and subtropical regions of the world. Different mangrove plant species protect and stabilize low lying coastal land, and provide protection and food sources for estuarine and coastal fishery food chains. Mangroves also serve as feeding, breeding and nursery grounds for a variety of fish, crustaceans, molluscs, reptiles, birds and other wildlife. 2. Sea Grass Sea grass beds are highly diverse and productive habitats that are home to hundreds of species of animals and plants including juvenile and adult fish, epiphytic and free-living macro-algae and micro-algae, bristle worms, nematodes, crustaceans, molluscs and reptiles. 3. Coral Reefs Coral reefs are warm, clear, shallow ocean habitats that are rich in life. The coral provides shelter for many animals including sponges, fish, jellyfish, anemones, sea stars, crustaceans, molluscs, sea turtles and sea snakes. 3 5. TROPICAL SEAS 4 5.1 MANGROVES 5.1 MANGROVES 5 5.1 MANGROVES 5.1 MAGROVES 5.1.1 Mangroves Mangroves forests are tropical, tidal salt-marsh forests dominated by mangrove trees and shrubs that have roots which are exposed at low tide. Mangroves are flowering trees that are tolerant to salty or brackish (mixed fresh and salt) water. They are found in coastal environments and salty mud flats near the shoreline where fine sediments, often with high organic content, collect in areas protected from high energy wave action. TYPES OF MANGROVE In Florida and the Caribbean, there are four types of mangrove: 1. Red Mangrove Red mangroves have long prop roots that reach down into the water. These roots serve as a nursery area for many coral reef fish and invertebrates. Most fish caught by fishermen on reefs need this habitat to mature, safe from predators and with a good food supply. The roots also protect the shoreline from wave erosion during storms. They also filter sediment from runoff coming off the land. Red mangrove wood is heavy and durable. The bark is used for tanning and medicinal purpose while the bark, leaves and shoots yield various dyes. 6 5.1 MANGROVES 2. Black Mangrove Black mangrove grows behind the red, in saturated soil where the trees breathe using roots called “pneumatophores” that project out of the soil. The leaves of the black mangrove are long and narrow. Excess salt is excreted through the leaves, where it can be seen crystallized on the leaves. 3. White Mangrove White mangroves can be found further inland, in moist sandy areas of lower salinity (salt content). Like the black mangrove, they also have the ability to excrete excess salt through tiny pores located at the base of each leaf. 4. Buttonwood Mangrove The Buttonwood mangrove is generally found furthest inland and has the largest leaves of them all. 7 5.1 MANGROVES 8 IMPORTANCE OF MANGROVES Mangroves are important for several reasons: (a) Nurseries Mangroves serve as feeding, breeding, and nursery grounds for a variety of fish, molluscs, birds, and other wildlife. Mangroves also produce a large amount of leaf litter per year which benefits estuarine food chains. In south Florida, an estimated 75% of the game fish and 90% of the commercial species depend on the mangrove system. (b) Preventing Erosion Mangrove roots are important in preventing erosion and the washing away of land into the ocean. Interesting! Mangroves have several adaptations that allow them to survive in an inhospitable environment. Black and white mangroves have special roots that grow vertically above the ground and act like snorkels. These roots allow the tree to absorb oxygen from the air when the ground is covered with salt water and the soil is low on oxygen. Black mangroves also excrete excess salt out through their leaves which can often be seen as salt crystals on the leaves. Red mangroves are the best adapted for living in salt water and can usually be found nearest the sea, often actually growing in the water. The roots of red mangroves resemble stilts and they allow the tree to stand in the water. They reproduce through large seeds called “propagules”, which look like darts, hanging from the ends of their branches. Each propagule is a small plant with roots already growing on it. When a propagule falls from the parent tree, it can grow directly in the muddy sediment or it can float along until the root end weighs it down into the correct position for it to grow. 5.1 MANGROVES 5.1.2 Mangrove Life 9 5.1 MANGROVES RED MANGROVE The red mangrove (Rhizophora mangle) is a tall tree that reaches 21-24 m (70-80 ft) in height in the tropics. In Florida, however, it is characterized as a short bushy tree reaching about 6 m (20 ft) in height. It is characterized by its numerous above ground roots called prop roots. The red mangrove grows in brackish areas along creeks, bays, and lagoons. MUDSKIPPER A mudskipper is a fish found in tropical coastal regions of Africa and Asia that is able to move on land on strong pectoral fins and breathe air. Mudskippers are uniquely adapted to an amphibious lifestyle and can breathe through their skin and the lining of their mouth and throat. However, this is only possible when the mudskipper is wet, limiting mudskippers to humid habitats and requiring that they keep themselves moist. Mudskippers are found in tropical and subtropical regions of the Indo-Pacific and the Atlantic coast of Africa, and are quite active when out of water feeding and interacting with one another, for example, to defend their territories. 10 5.1 MANGROVES ALLIGATORS, CAIMANS, CROCODILES & GHARIALS Alligators are found in the southern United States and eastern China. Caimans are found in Central America and South America. Crocodiles are found in Mexico, Central and South America, Africa, Southeast Asia and Australia. They live in grassy swamps and slow-moving rivers. Gharials live in Indian rivers with deep pools and sand or mud banks, and eat fish. All crocodilians are carnivores and eat whatever they can catch in the water or along the banks, including fish, turtles, frogs, birds, pigs, deer, buffalo, and monkeys, depending on the size of the animal. The crocodilians don't chew their food; they tear bite-sized pieces off a carcass or swallow small prey whole. The saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus) is the world's largest reptile. These amazing creatures are found on the northern coast of Australia and inland for up to 100 km (62 miles) or more. Saltwater crocodiles grow to lengths of 7 m (23 ft) but the average size of is 4 m (12 ft) long. 11 5.1 MANGROVES 12 REFERENCES & FURTHER READING http://www.sfrc.ufl.edu/4H/Other_Resources/Contest/Highlighted_Ecosystem/Mangrove%20Forests.htm - Florida's Mangrove Forest Ecosystem http://www.nationaltrust.org.ky/info/mangroves.html - Mangroves http://www.nationaltrust.org.ky/info/centralmangrove.html - Mangroves of Cayman Islands http://mangrove.nus.edu.sg/guidebooks/contents.htm - Mangroves of Singapore http://www.sfrc.ufl.edu/4h/Red_mangrove/redmangr.htm - Red mangrove http://www.epa.gov/owow/wetlands/types/mangrove.html - Mangroves http://www.stx.k12.vi/torch99/fldtrp/mangrove.htm - Mangroves http://www.enchantedlearning.com/subjects/mammals/manatee/ - Manatees http://www.sandiegozoo.org/animalbytes/t-crocodile.html - Crocodilians http://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/cnhc/csl.html - Crocodile species Byatt, Andrew, Fothergill, Alastair and Holmes, Martha, The Blue Planet: Seas of Life, Chapter 3, DK Publishing Inc., (2001), ISBN 0-7894-8265-7 5.2 SEA GRASSES 5.2 SEA GRASSES 13 14 5.2 SEA GRASSES 5.2 SEA GRASSES 5.2.1 Sea Grasses Sea grasses are flowering plants that live and grow in the marine environment. There are about 60 species worldwide and they are from one of four plant families as follows: Family Posidoniaceae Posidonia Family Zosteraceae Zostera (Eelgrass) Heterozostera Phyllospadix Family Hydrocharitaceae (Frogbit family) Enhalus Halophila Thalassia (Turtle Grass) Family Cymodoceaceae Amphibolis Cymodocea Halodule Syringodium Thalassodendron SEA GRASS 5.2 SEA GRASSES 15 Sea grasses are plants so they must photosynthesize to survive and must grow in the photic (light penetrating) zone of the ocean. Most sea grasses are found in shallow and sheltered coastal waters anchored in sand or mud bottoms. They undergo pollination while submerged and complete their entire life cycle underwater. Sea grasses form extensive beds that can be either mono-specific (made up of just one species) or multi-specific (where more than one species co-exist). Tropical sea grass beds can be diverse (e.g. 13 species recorded in the Philippines). In temperate areas, however, usually one or just a few species dominate (e.g. Common Eelgrass (Zostera marina) in the North Atlantic). Sea grass beds are highly diverse and productive ecosystems and can harbor hundreds of species including juvenile and adult fish, epiphytic and free-living macroalgae and microalgae, bristle worms, and nematodes, crustaceans and molluscs. Sea grass herbivory is a highly important link in the food chain with hundreds of species feeding on sea grasses including dugongs, manatees, fish, geese, swans, sea urchins and crabs. Sea grasses are sometimes labeled ecosystem engineers because they partly create their own habitat – their leaves slow down water-currents increasing sedimentation and the sea grass roots and rhizomes stabilize the seabed. Their importance is mainly due to their provisioning of shelter to associated species (through their three-dimensional structure in the water column) and for their extraordinarily high rate of primary production. Sea grass areas are important fishing grounds, wave protection, oxygen production, and protection against coastal erosion. 5.2 SEA GRASSES 5.2.2 Sea Grass Life 16 17 5.2 SEA GRASSES SEA GRASS One type of sea grass – turtle grass – is characterized by its flat, strap-like blades. Blades can be 76 cm (30 in) tall and 4.0 cm (1.5 in) wide. There are 9-15 parallel veins per blade. Rhizomes are thick and tough, with an extensive root system that anchors the rhizomes to the substrate. Scaly flowers, generally whitish-green to pink in colour, are produced. Fruits are rounded and pod-like. Turtle grass grows in the sub-tidal zone from approximately the low tide line to depths of 9 m (30 ft) or more. In clear waters, depth can be up to 27 m (90 ft). Sheltered areas having muddy substrates are prime habitat. Turtle grass ranges throughout the tropical western Atlantic from east central Florida south through the Gulf of Mexico, Central and South America to Venezuela. SEA TURTLE Sea turtles are large air-breathing reptiles with paddle-shaped foreflippers and a number of other adaptations that make them perfectly at home in the ocean. Today, only seven species remain worldwide – green, loggerhead, hawksbill, flatback, Kemp’s ridley, olive ridley, and leatherback turtle. Although they may live their entire life at sea, sea turtles must return to the land to nest. Under cover of darkness, a female will drag her body across a sandy beach where she will dig a nest and deposit about 100 eggs in the warm sand. After about 60 days of incubation, the eggs will hatch and the hatchlings will make their way back to the sea. SEA GRASS 5.2 SEA GRASSES SPOTTED EAGLE RAY Spotted Eagle rays have dark grey to brown bodies with a pattern of white spots and streaks above and are whitish below. They also have long graceful “wings” (pectoral fins) that can reach 2.4m (8 ft) across and a long whip-like tail with a long spine near base. They can be found in sea grass, on coral reefs, or in the open sea in large schools during non-breeding season. MANATEES & DUGONGS Manatees belong to the Sirenian family which includes the Amazonian manatee and the African dugong. The average adult manatee grows to be about 3.6 m (12 ft) long and weighs about 800 kg (1,800 lbs). When manatees are newborn, their skin is greyblack which lightens to grey as they mature. Manatees breathe air and can stay underwater for up to 20 minutes although surfacing every 5 minutes is more usual. Their nostrils are covered by flaps that close during dives. A manatee's life span is roughly 60 years. Manatees live in warm, shallow waters along coasts, in estuaries, and canals. They can live in salt, fresh or brackish waters. Manatees are found along the Gulf Coast of the USA (wintering in Florida) and in many waterways in South America. Manatees are endangered and their numbers are dwindling. 18 5.2 SEA GRASSES Dugongs are closely related. Dugongs are large grey mammals with nostrils near the top of their snouts and bristles near their mouths. They have two flippers, each of which has three to four nails, and they have no hind limbs. Fully grown, they may be 3 m (10 ft) long and weigh 400 kg (882 lbs). Dugongs swim by moving their broad fluke-like tail in an up and down motion and using their two foreflippers. Dugongs are highly migratory. In Australia, dugongs swim in the shallow coastal waters of northern Australia. They are also found in other parts of the Indian and Pacific Oceans in warm shallow seas where sea grass is found. They surface only to breathe and never come on to land. Female dugongs give birth underwater to a single calf at 3 to 7 year intervals. The calf stays with its mother, drinking milk from her teats and following close by until 1 or 2 years of age. Dugongs reach adult size between 9 and 17 years of age. Dugongs are sometimes called “sea cows” because they graze on sea grasses. Dugongs are slow-moving and have few defenses against predators but, because they are large animals, only large sharks, saltwater crocodiles and killer whales are a danger. REFERENCES & FURTHER READING http://www.seagrasswatch.org/home.html - Sea grass monitoring http://www.abc.net.au/oceans/jewel/grass/default.htm - Sea grass http://sanctuaries.noaa.gov/welcome.html - National Marine Sanctuaries http://www.environment.gov.au/coasts/species/dugongs/index.html - Dugongs 19 5.3 CORAL REEFS 5.3 CORAL REEFS 20 5.3 CORAL REEFS 5.3 CORAL REEFS 5.3.1 Coral Reefs Coral reefs are warm, clear, shallow ocean habitats that are rich in life. The reef's massive structure is formed by coral polyps – colonies of tiny, invertebrate animals (cnidarians). Each coral polyp secretes a hard calcium carbonate (limestone) cup around itself. These cups are fused with cups from other members of the colony to form large boulder, branching and platy shaped rock-like structures. When an individual coral polyp dies, it leaves behind its skeletal cup. A coral reef provides shelter for many animals including sponges, sea stars, crustaceans, molluscs, fish and sea turtles. TYPES OF REEF Coral reefs form when free-swimming coral larvae attach to the submerged edges of islands, continents, or hard substrate. As the corals grow and expand, reefs take on one of three major characteristic structures — fringing, barrier or atoll. 1. Fringing reefs – fringing reefs, which are the most common, project seaward directly from the shore, forming borders along the shoreline and surrounding islands. They grow on the continental shelf or around islands in shallow water. 21 5.3 CORAL REEFS 2. Barrier reefs – barrier reefs also grow parallel to shorelines but are further out and usually separated from the land by a deep lagoon. They are called barrier reefs because they form a barrier between the lagoon and the seas. Two of the most famous are the Great Barrier Reef off the coast in Australia and the Meso-American Barrier Reef off the coast of Belize. 3. Coral atolls – coral atolls are rings of coral that grow on top of sunken volcanoes in the ocean. They begin as fringe reefs surrounding a volcanic island; then, as the volcano sinks, the reef continues to grow until, eventually, only the reef remains. Atolls are usually circular or oval, with a central lagoon. Parts of the reef platform may emerge as one or more islands, and breaks in the reef provide access to the central lagoon. 22 5.3 CORAL REEFS CORAL REEF DISTRIBUTION Coral reefs are mostly found in the tropics in warm (21°C-30°C (70°F-85°F), shallow water. They are found off the east coast of Africa, the south coast of India, in the Red Sea, and off the coasts of northeast and northwest Australia. There are also coral reefs off the coast of Florida and in the Caribbean. The Great Barrier Reef (NE Australia) is the largest coral reef in the world and is over 2,000 km (1,257 miles) in length. The Mesoamerican Barrier Reef is the second longest barrier reef in the world and extends from the southern half of the Yucatan Peninsula in Mexico through Belize to Honduras. REFERENCES & FURTHER READING http://www.coris.noaa.gov/about/what_are/ http://www.enchantedlearning.com/biomes/coralreef/coralreef.shtml 23 5.3 CORAL REEFS 5.3.2 Coral Reef Life 24 5.3 CORAL REEFS HARD CORALS Corals can be considered as either hard or soft depending on their consistency and the nature of their skeletons. Hard corals are reefbuilding corals that secrete a hard external limestone skeleton. This skeleton remains when the corals die and forms a base upon which other corals can grow. Hard corals grow in three basic forms, namely, massive, branching, and plate. Examples include brain coral (a massive coral), elkhorn and staghorn corals (branching corals), and leaf coral (a plate coral). In the Cayman Islands, about 44 species of hard coral can be found. SOFT CORALS Soft coral polyps form a skeleton by secreting a flexible horn-like substance (gorgonin) into which calcium carbonate (limestone) is embedded. This arrangement results in the formation of pliable bushy or fan-shaped colonies. Soft corals also extend their polyps during the day to capture prey which adds to the illusion of their being fuzzy bushes or intricately-branched trees and some of the most common are the sea fans, sea fingers and sea whips. 25 5.3 CORAL REEFS SPONGES Sponges are conglomerations of simple cells and are some of the most primitive invertebrate animals surviving today. They are composed of an internal skeleton of needle-sharp spicules that are interwoven with strands of protein (spongin) to give the sponge its tough and rubbery texture. Many varieties of sponge can be found in Florida and the Caribbean including the commonly seen basket, vase and tube sponges. Sponges feed on phytoplankton and zooplankton by drawing in water through pores in their skin. The water is then propelled by flagella through a series of canals and chambers, from which food is filtered, before it is expelled from large vents, called oscula. SEA STAR Sea stars (or starfish) are soft-bodied marine animals with five arms. Sea stars are echinoderms, a large group of invertebrates which include sea urchins, sand dollars, sea cucumbers and brittle stars. Sea stars typically live in the middle of a tidal range and can survive short periods of exposure to air as the tide retreats. 26 5.3 CORAL REEFS SEA URCHIN Sea urchins are echinoderms. They are round, spiny and herbivorous invertebrates that graze on algae and detritus from grass beds and rocky areas. Many sea urchins have long, sharp spines on their backs, which protect them from predators such as fish, crabs, moray eels and sea otters. However, their underside is often spineless and they are vulnerable to attack from that side if the predator can turn the sea urchin over. HERMIT CRAB Hermit crabs are decapod crustaceans. Most hermit crabs have long soft abdomens which they protect by living inside the empty seashells of sea snails (marine gastropod molluscs). The tip of the hermit crab's abdomen is adapted to clasp strongly onto the snail shell. There are about 500 species of hermit crabs in the world mainly living on shallow coral reefs and shorelines or deep sea bottoms. In the tropics, however, some species are terrestrial and can be large, such as the soldier crab (Coenobita clypeatus) and coconut crab (Birgus latro). The coconut crab is the world’s largest arthropod weighing up to 4 kg (9 lbs) and with a leg span of 2 m (6 ft). 27 5.3 CORAL REEFS 28 FISHES A wide variety of reef fishes can be found on Caribbean reefs. Some common fish families include: Bony Fish Families: Angelfish Butterflyfish Damselfish – Sergeant Majors Goatfish Grunts Jacks Moray eels Parrotfish Sea basses Snappers Surgeonfish Tarpon Triggerfish Wrasses Cartilaginous Fish Families: Eagle rays Stingrays Nurse sharks Requiem sharks – bull shark, sandbar shark, whitetip reef shark Interesting! Parrotfish bite out chunks of the rock-hard coral to dredge out the algae around and within it for food. In order to rasp the encrusting algae from the corals, Parrotfish use a set of teeth that are fused into solid plates and are ideal for biting the rock-hard coral skeletons. The parrotfish's ingestion and excretion of the undigested coral skeletons is thought to be the main source of the white sand so often seen and admired on tropical beaches. 5.4 OCEAN LIFE 5.4 OCEAN LIFE 29 5.4 OCEAN LIFE 5.4 OCEAN LIFE 5.4.1 Cnidarians If you’ve ever been stung by anything in the ocean, the chances are that it was probably by one of the cnidarians. It might have been a moon jellyfish in which case the sting was probably scarcely noticeable. Alternatively, you might have brushed up against a fire coral in which case the sting was mildly painful. However, if it was a Portuguese man-of-war, the sting would have been excruciatingly painful. The word “cnidarian” is pronounced “ne-dare-ee-an” or “nigh-dareee-an” (the “c” is silent) and comes from the Greek word “cnidos” which means “nettle”. This is somewhat appropriate as all cnidarians have stinging cells. The cnidarians count some of the oldest, largest and most poisonous creatures on Earth among them. Some of their features are as follows: 30 Interesting! Many scientists are trying to get away from using the term “jellyfish” and using the term “jellies” instead because jellyfish are not “fish” but invertebrates and members of the cnidarian phylum. Interesting! A group of fish is called a “school”. A group of jellyfish is known as a “smack”. 5.4 OCEAN LIFE Ancient simple animals Fossil records date back to the Precambrian era (about 550 million years ago) Very diverse; about 10,000 species Extremely varied and range in size from a few millimeters to over 30 meters in length With few exceptions, the cnidarians are marine animals All are predators and carnivorous; major part of their diet consists of crustaceans and fish Cnidarians spend their lives in sessile polyp form, free-swimming medusa form, or a mix In polyp form, tentacles oriented upwards; in medusa form, tentacles oriented downwards Both asexual (polyp form) and sexual (medusa form) reproduction occurs No specialized excretory or respiratory organs but do have gonads & simple nervous system There are four major classes of cnidarians: 1. Anthozoa – Sea anemones, Corals 2. Hydrozoa – Siphonophores, Hydroids 3. Scyphozoa – True Jellyfish 4. Cubozoa – Box Jellyfish 31 5.4 OCEAN LIFE 32 CNIDARIAN CLASSIFICATION 5.4 OCEAN LIFE 33 CNIDARIAN FEATURES BODY A cnidarian’s body consists of a sac with a digestive cavity and a single opening that functions as mouth and anus. Tentacles surrounding the mouth contain stinging cells for offense and defense. A cnidarian has radial symmetry (i.e. whichever way it is cut along its central axis, the resulting halves are mirror images of one other). A cnidarian is composed of two layers of tissue, called the ectoderm and endoderm (or gastroderm), which are held together by a gelatinous mesoglea containing only scattered cells. STINGING CELLS (“NEMATOCYSTS”) Cnidarians have specialized cells that carry stinging organelles called nematocysts. These specialized stinging structures are a characteristic of the phylum and are borne in the tentacles and other body parts. Cnidarians employ these stinging cells to kill prey. The nematocysts function by a chemical or physical trigger that causes it to eject a coiled fiber with a barbed and poisoned hook that can stick into prey. Dead or paralyzed prey is pushed into the cnidarian's oral opening by the tentacles and digested in the gastrovascular cavity. All undigested food, waste & other secretions leave through the same oral opening. BODY FORMS & LIFESTYLES The cnidarians have two characteristic body forms and lifestyles. The sessile polyp form is more or less cylindrical, attached to its substratum at its aboral (opposite the mouth) end, with the mouth and surrounding tentacles at the upper (free) end. The motile medusoid form is flattened, with the tentacles usually located at the body margin. Generally, the cnidarians have life-cycles that alternate between asexual polyps and sexual free-swimming medusae although there is considerable variation within this pattern. For example, the Anthozoan medusal stage is virtually non-existent – once the larva fuses with the substratum and develops into the polyp, it grows sessile and no longer metamorphosizes into the medusal stage. Among the Scyphozoans and Cubozoans, the medusae are the dominant form in the life-cycle, and the polyps are in turn reduced or absent. 5.4 OCEAN LIFE ANTHOZOA – SEA ANEMONES, CORALS 1. Sea Anemones Sea anemones are simple animals (cnidarians) that are often attached to the sea bottom. Sea anemones have cylindrical bodies that are surrounded by upward-facing tentacles. The tentacles have stinging cells on them which kill prey and move the food into a sea anemone’s mouth. The mouth leads into the body cavity which digests the food. A continuous current of water through the mouth circulates through the body cavity and removes waste. Sea anemones are found in cold and warm waters. Many are colourful, and large species can be 1 m (3 ft) in diameter. 2. Corals Corals are often misperceived as rock or vegetation but they are actually colonies of simple animals. A ring of tentacles is found at the upper end of each coral polyp. The tentacles contain poisonous stinging cells (nematocysts) that are used to kill zooplankton or fish. As the prey drops, it is funnelled by the tentacles into the mouth and digested in the digestive cavity. The food obtained by one polyp can also be passed to other polyps in the colony and a coral, therefore, does not have a single mouth but hundreds or thousands, each of which serves to feed the animal as a whole. 34 5.4 OCEAN LIFE Coral polyps also contain symbiotic algae called zooxanthellae within their digestive cavity. The polyps benefit from the oxygen produced in the algal photosynthesis reaction and from the removal of carbon dioxide waste produced by polyp respiration. The zooxanthellae benefit from the ammonia waste excreted by the polyps as it can be broken down and used by the algae to build proteins. In addition, the polyps provide the algae with carbon dioxide from their respiration, necessary for algal photosynthesis. Corals have two main consistencies – hard/stony or soft. Hard Corals A hard coral polyp secretes a calcium carbonate (limestone) cup around itself, which is fused with others to form boulder or rock-like structures. This process is slow but the efforts of one generation are not lost for subsequent generations can build over the skeletal cups of their ancestors allowing the coral to spread over a reef. An example of a hard coral is brain coral. Soft Corals In contrast, soft coral polyps secrete a horn-like substance (gorgonin) into which calcium carbonate is embedded. This arrangement gives the soft corals greater flexibility than their hard coral counterparts, allowing them to form more pliable bushy or fanshaped colonies. An example of a soft coral is the purple sea fan. 35 5.4 OCEAN LIFE Corals Reefs Worldwide: Great Barrier Reef Belize Red Sea Caribbean, etc. 36 5.4 OCEAN LIFE Problems: 1. Climate Change A sobering study by the World Conservation Union released in October 2005 determined that nearly half of the world's coral reefs may be lost in the next 40 years unless urgent measures are taken to protect them against the threat of climate change. “Coral Bleaching” – algae give corals their multi-colours; when water is too warm, the algae are ejected. Without the symbiotic algae, coral skeletal growth and repair rates are slower and the coral may die. 2. Pollution Corals cannot clean themselves of some forms of pollution. Other forms of pollution cause corals to secrete too much mucus which leads to infection. 3. Physical Damage Natural forces (e.g. storms) Humans (e.g. boat anchors, swimmers, divers) 4. Slow Growth Rates Many corals grow slowly (perhaps only 1 cm (0.5 in) per year) and it can take many years to repair damage. 37 5.4 OCEAN LIFE HYDROZOA – SIPHONOPHORES, HYDROIDS A siphonophore resembles a jellyfish but it is not actually an individual organism. Siphonophores, such as the Portuguese Manof-War, are really colonies of specialized individuals so that, in extreme cases, individuals essentially function as organs of the whole. For example, one individual in the group transforms itself into a gas-filled float while others form stinging tentacles that kill prey. A Portuguese Man-of-War's tentacles hang well below the float and can be up to 9 m (30 ft) long. Stinging cells at the tips are used to kill prey, such as crustaceans, fish, and plankton. The prey is then lifted into the colony's float, where other members do the work of digestion. Nutrients are shared through a connected gut system and a network of nerves helps the individuals communicate. A Portuguese Man-of-War's sting is extremely painful to humans and wounds may not heal for weeks. Similarly, hydroid colonies are also comprised of several different types of individuals: some function in feeding, some in defence, and others in reproduction. Other hydrozoans form massive colonies that resemble true corals. For example, the so-called “fire corals” are not really corals at all but hydrozoans. Hydrozoans alternate between sessile polyp & free-swimming medusa stage. 38 39 5.4 OCEAN LIFE SCYPHOZOA – TRUE JELLYFISH No head, skeleton or special organs for respiration and excretion Stings vary in potency – mild to highly potent Huge range in size from 12mm to 2m across the bell The collective noun for a group of jellyfish is a “smack” Alternate between sessile polyp & free-swimming medusa phase; medusa phase dominates Moon jellyfish (Aurelia sp.) To 300mm (12 in) across bell Stings mild to humans Red-striped sea nettle (Chrysaora fuscescens) To 1 m (3 ft) diameter, tentacles 5 m (15 ft) Found from Alaska (AK) to California (CA) Lion’s mane jellyfish (Cyanea arctica) To 2m diameter; tentacles >40m (130 ft) Stings very painful to humans Interesting! The lion’s mane jellyfish is one of the world’s longest animals with tentacles reaching more than 40 m (130 ft). 5.4 OCEAN LIFE CUBOZOA – BOX JELLYFISH Look like basic jellyfish but are square or box shaped Tentacles are evenly spaced on each corner of the bell Have well-developed eyes and can see fairly well May also have a rudimentary brain Most jellyfish drift but box jellyfish can swim quite quickly Sometimes called sea wasps About 20 species found in tropical and sub-tropical waters Cubozoans can be divided into two groups: 1. Chirodropids Stinging cells usually only on tentacles Usually larger: Chironex fleckeri 300-385 mm (12-15 in) across bell Multiple tentacles per corner of bell. For example, Chironex fleckeri (large box jelly) has up to 60 tentacles (15 per corner of the bell) 2. Carybdeids Stinging cells on both body & tentacles Usually smaller: Carukia barnesi 10 mm (0.4 in) across bell Usually one tentacle per corner of bell. For example, Carukia barnesi has 4 retractile tentacles (1 per corner of the bell) each up to 750 mm (30 in) long. 40 5.4 OCEAN LIFE Some box jellyfish are intensely poisonous and can cause human fatalities. The bell of the Australian Irukandji jelly, Carukia barnesi, for example, is only about the size of a human fingernail (1 cm) and its tentacles are like long thin threads. The sting may be extremely painful for several weeks and can sometimes kill humans. REFERENCES & FURTHER READING http://www.earthlife.net/inverts/cnidaria.html – The Phylum Cnidaria http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/cnidaria/cnidaria.html – Introduction to Cnidaria http://www.ucmp.berkeley.edu/cnidaria/Chironex.html - Chironex http://www.tolweb.org/tree?group=Cnidaria – Cnidaria http://www.reef.crc.org.au/publications/brochures/Stingingjellyfishfront.htm – Jellyfish in Australia http://www.iucn.org – World Conservation Union 41 5.4 OCEAN LIFE 5.4.2 Reef Fish There are about 350 different marine fish species in the Caribbean. To differentiate between them, it is often helpful to initially classify them according to their various characteristics. All fishes are classed as either jawless or jawed vertebrates: 1. JAWLESS FISHES Jawless fishes, such as lampreys & hagfishes, are primitive fishes with no jaws, scales, pelvic or pectoral fins. Lampreys are both parasitic and non-parasitic. Parasitic lampreys cling to their prey by suction with their oral disk. They rasp a hole in their prey and suck out its blood and body fluids. Non-parasitic lampreys do not feed as adults. Most lampreys live in freshwater; those that enter the sea return to rivers to spawn. Hagfishes scavenge on dead or dying fishes by rasping their way into the fish and eating the flesh. Hagfishes produce great quantities of slime and have vestigial eyes that are covered by skin. Hagfishes are marine and usually found in deep cold water. 42 Interesting! The plural of fish can be fish or fishes. The distinction depends on the number and species of fish. If you have more than one fish but they are the same species then the plural is “fish”. For example, if I have three flounders, I have three fish. If there is more than one species then the plural is “fishes”. Thus, if I have two flounders and one skate, I have three fishes. 5.4 OCEAN LIFE 2. JAWED FISHES Jawed fishes are further divided into bony or cartilaginous fishes. (A) BONY FISHES Bony fishes have skeletons made of bone. Bony fish are subdivided into many different orders and families such as angelfish, butterflyfish, damselfish, goatfish, grunts, jacks, moray eels, parrotfish, sea basses, snappers, surgeonfish, tarpons, triggerfish, & wrasses. Bony fish have cycloid (round), ctenoid (comb-like) or ganoid (diamond-shaped) scales, and a pair of gill covers, and most bony fish also have swim bladders to control their buoyancy. (B) CARTILAGINOUS FISHES Cartilaginous fishes have skeletons primarily made of cartilage and most have sharp, placoid (plate shaped) scales covering their skins. Cartilaginous fishes have no gill covers or swim bladders and use large, oil-filled livers to help keep them buoyant. The best known cartilaginous fishes are the sharks & rays. Sharks and rays are further divided into multiple orders and families such as the requiem, sand tiger and nurse shark families and the skate, sawfish, eagle ray, and devil ray families. There are about 30 families and 355 species of sharks, and 11 families and 470 species of rays. 43 5.4 OCEAN LIFE 44 5.4 OCEAN LIFE ANGELFISH Angelfish bodies are deep and about the size of a dinner plate They are diurnal Eat sponges; unusual as many animals cannot eat sponges Usually found singly or in pairs E.g. French angelfish (Length to 30 cm or 12 in) Black with yellow-edged scales Young French angelfish will act as cleaners for other fish Juvenile French angelfish are striped Become mottled as they mature 45 5.4 OCEAN LIFE BUTTERFLYFISH Butterflyfish bodies are deep and flattened with bright colours and patterns on them Long, pointed mouths for plucking out coral polyps as food Feed mainly on hard and soft corals (gorgonians), polychaete worms, and tunicates Typically seen singly or in pairs and are active during the day E.g. Foureye butterflyfish (Length to 8 cm or 3 in) White body with large “spot” below rear of dorsal fin – spot is on body Dark, diagonal lines that meet at the mid-side of the body DAMSELFISH Territorial and guard patches of coral Have little fear – will even come at divers if they get too close Lay adhesive eggs in clusters on hard surfaces; nest guarded by male Produce chirping sounds; used in courtship, territorial defence & species recognition E.g. Sergeant major (Length to 18 cm or 7 in) Bright yellow above, silvery grey below with 5 stripes Eats algae and various invertebrate larvae Adults form large feeding groups of up to several hundred fish 46 5.4 OCEAN LIFE EAGLE RAYS Large, free-swimming rays; “fly” through the water by flapping their long pectoral fins Gather in schools of hundreds or thousands Feed on bottom organisms such as molluscs and clams Have flattened teeth which are suited to crushing shellfish Have a strong, serrated, venomous spine near base of tail (like stingrays) Individuals occasionally seen with chunks missing from a “wing” due to shark bites E.g. Cownose ray (To 1 m or 3 ft across disk) Dark brown to olive above with no spots or marks Snout squarish with an indentation in the centre Bears live young (like all eagle rays) GOATFISH Bottom-dwelling fishes that have long, fleshy “barbels” (“whiskers”) under their chin Swim along the sandy bottom stirring sand with their barbels to locate food E.g. Yellow goatfish (Length to 38 cm or 15 in) Yellow stripe from eye to yellow caudal fin Feeds on bottom-dwelling invertebrates Often found in schools Forms schools with smallmouth grunts possibly for protection 47 5.4 OCEAN LIFE GRUNTS Tend to feed at night and congregate by day in large schools on reefs Grind their teeth; this makes a grunting noise hence their name E.g. Porkfish (Length to 38 cm or 15 in) Two black bars on head and front part of body Body with alternating blue and yellow stripes; fins yellow Young remove parasites from other fish JACKS Large, strong, fast-swimming fishes Predatory; feed on a wide variety of invertebrates and fishes Lack bright colours; silvery on sides and darker above Important food and game fish E.g. Lookdown (Length to 30 cm or 12 in) Body is extremely compressed and deep Front of head very steep 48 5.4 OCEAN LIFE MORAY EELS Morays are predators that feed on fishes, octopuses, crustaceans and molluscs No pectoral fins; dorsal, caudal & anal fins continuous hence “snake-like” appearance Gill opening reduced to a single circular opening Habit of gaping is not usually a threat but for respiration Have long, sharp teeth and powerful jaws that can crush bone E.g. Blackedge moray (Length to 53 cm or 21 in) Dark brown with pale spots; dorsal fin black edged (hence name) E.g. Green moray (Length to 2.4 m or 96 in) Green coloration is caused by a yellowish mucus blending with its dark blue body colour NURSE SHARK Nurse Shark Family Rusty brown with small yellowish eyes No nictitating membrane on eye Mouth small; teeth in a crushing series Feeds on crustaceans and shellfish Use their thick lips to create suction and pull prey from holes & crevices Has “barbels” (“whiskers”) front edge of each nostril Barbels used to find food on the ocean bottom. Caudal fin with no distinct lower lobe Will bite if provoked but otherwise relatively harmless Large eggs in horny capsules Length to 4.3 m (14 ft) but usually less than 3 m (10 ft) 49 5.4 OCEAN LIFE PARROTFISH Parrot-like beak from fused teeth Eat corals and algae Swim using their pectoral fins E.g. Blue parrotfish (Length to 122 cm (4 ft); usually 61 cm (2ft)) Sky to royal blue body Blunt snout Teeth white SANDBAR SHARK Requiem Shark Family Heavy body Dark grey to brown above; becoming paler below Infamous relatives are the Bull, Tiger and Oceanic Whitetip sharks Bears live young (like all requiem sharks) Length to 3 m (10 ft) 50 5.4 OCEAN LIFE SEA BASSES The sea bass family consists of sea basses and groupers. Sea bass family: Small to very large fishes with 7-11 spines on dorsal fin Mainly tropical fishes but are also found in temperate shores Important food fish for humans Usually solitary and territorial; non-schooling fishes E.g. Chalk bass (Length to 6.4 cm or 2.5 in) Orange-brown above with pale blue bands; top of head un-scaled Have 10 spines in dorsal fin Synchronously hermaphroditic Common near coral reefs SNAPPERS Predatory fish Snappers from deeper, rocky slopes are usually red; reef types are tan and yellow Important food and game fish E.g. Yellowtail snapper (Length to 76 cm or 30 in; 2.3 kg / 5 lbs) Bright yellow stripe from snout tip to caudal fin Quite common on a reef and will often follow divers around E.g. Vermillion snapper (Length to 76 cm or 30 in) Head, body, and fins entirely pale red becoming silvery below; protruding lower jaw 51 5.4 OCEAN LIFE STINGRAYS Most stingrays eat clams, mussels, and oysters Have flattened teeth which are suited to crushing shellfish Have a thin, whip-like tail with one or more barbed spines near the base of the tail E.g. Southern stingray (To 53 cm or 21 in across disk) Disk almost perfect rhombus Most stingrays are bottom-dwellers; often lie submerged in sand except for the eyes Whip-like tail with venomous spine; note: spine venomous, not the tail itself Bears live young (like all stingrays) SURGEONFISH Named for the spine on each side of the caudal peduncle. This spine folds forward against the body like the blade of a pocket-knife. Spine can inflict painful wounds if fish is grasped around the caudal peduncle. E.g. Blue tang (Length to 23 cm or 9 in) Uniformly bright blue body usually with narrow dark lengthwise lines Narrow yellow line where spine folds against caudal peduncle 52 5.4 OCEAN LIFE TARPONS Large, powerful, predatory fish Important game fish E.g. Tarpon (Length to 2.4 m or 96 in and 136 kg or 300 lb) Silvery Large mouth; protruding lower jaw Very large scales TRIGGERFISH 3 dorsal spines with locking device; the first one long and strong; the other two spines small Scales regular, plate-like, forming coarse armour over body Most triggerfish produce grunting sounds Mouth small but jaws strong and teeth well-developed Triggerfish eat crustaceans (crabs, lobsters), octopuses, sea urchins and corals Will bite off crustacean limbs and sea urchin spines using their teeth and jaws like bolt-cutters E.g. Queen Triggerfish (Length to 61 cm or 24 in) Bluish; orange chin and chest; bright blue and gold marks 53 5.4 OCEAN LIFE 54 WRASSES Varied in size from very small to huge Swim by flapping pectoral fins Most are non-schooling Most have protruding teeth E.g. Hogfish (Length to 90 cm or 36 in) Body deep; reddish; dark mask; 3 long dorsal spines REFERENCES & FURTHER READING http://www.fishbase.org Robins, C.R. et al., A Field Guide to Atlantic Coast Fishes of North America, Houghton Mifflin Pub. (1986) 5.4 OCEAN LIFE 55 5.4.3 Sea Turtles Sea turtles are reptiles that are part of the turtle and tortoise order. A sea turtle’s body is partially covered by a shell. This shell consists of two parts; an upper carapace and a lower plastron. Unlike other turtles, a sea turtle’s head & flippers cannot be pulled inside of its shell. There are 7 species: Green Loggerhead Hawksbill Flatback Kemp’s Ridley Olive Ridley Leatherback All species have shells with horny scales (“scutes”) except the leatherback which is covered with leathery skin. The leatherback is one of only a few reptiles capable of regulating its internal body temperature. 56 5.4 OCEAN LIFE HOW LARGE ARE SEA TURTLES? HOW LONG DO THEY LIVE? The largest sea turtle is the leatherback, which has a carapace length of about 1.6 m (64 in) and can weigh 590 kg (1300 lbs). Sea turtles can possibly live over 100 years depending on species. The following outlines the weight and average carapace length of the sea turtles: Species Green Weight Length 136-227 kg 300-500 lbs 99 cm 39 in 91-159 kg 200-350 lbs 84-102 cm 33-40 in 40-73 kg 89-160 lbs 76-91 cm 30-36 in 71 kg 156 lbs 76-97 cm 30-38 in 35-45 kg 78-100 lbs 61-71 cm 24-28 in Olive Ridley < 45 kg < 100 lbs 56-76 cm 22-30 in Leatherback 363-590 kg 800-1300 lbs 162 cm 64 in Loggerhead Hawksbill Flatback Kemp’s Ridley 57 5.4 OCEAN LIFE WHERE ARE SEA TURTLES FOUND? Sea turtles are found in many of the world’s oceans. Green Temperate and tropical waters Atlantic (Central America, Bahamas, U.S.) Pacific (Baja, CA to Peru) Loggerhead Temperate and subtropical waters Newfoundland to Argentina Hawksbill Tropical Atlantic, Pacific, Indian Oceans Flatback Tropical Australia northern coastal waters only Kemp’s ridley Temperate and tropical waters Gulf of Mexico. Juveniles along eastern seaboard of the USA to Cape Cod Olive ridley Tropical waters Mainly in Pacific and Indian Oceans, a few in Atlantic Leatherback Arctic to tropical waters Canada, Iceland, Norway, NZ, Chile 5.4 OCEAN LIFE WHAT DO SEA TURTLES EAT? Sea turtles feed on a variety of items including turtle grass, jellyfish, sponges, fish and crustaceans. HOW DO SEA TURTLES REPRODUCE? A female sea turtle come ashore to lay her eggs. The female digs a burrow with her hind legs, lays a batch of eggs and covers them with sand. The temperature of the sand on the beach determines the sex of the hatchling – warmer temperatures result in female hatchlings; cooler temperatures result in male hatchlings. Hatchlings dig their way out of the burrow and head for the sea. WHY DO MOST TURTLES NEVER MAKE IT TO ADULTHOOD? Hatchlings and young turtles are preyed upon by many predators (e.g. raccoons, crabs, foxes, sea birds and large fish). Sea turtles are hunted by humans for meat, eggs, skin and shells to produce face cream, cosmetics and souvenirs. Habitat destruction has also drastically reduced the number of available beaches for breeding. As a result, only 1% of sea turtle eggs will make it to adulthood. 58 5.4 OCEAN LIFE 59 WHAT IS THE “ARRIBADA”? All sea turtles have solitary nesting except the Ridleys which arrive and nest as a mass. This is called the “arribada” or the “arrival” in Spanish. WHY ARE GREEN TURTLES BROWN? The green turtle is named for its green body fat (“calipee”) not its carapace colour. Calipee is used in making turtle soup. WHAT IS THE STATUS OF SEA TURTLES? All sea turtles are either endangered or threatened. Sea turtles are protected in the USA under the Endangered Species Act and around the world by CITES (Convention on the International Trade of Endangered Species of Flora and Fauna). REFERENCES & FURTHER READING http://www.cccturtle.org http://www.seaworld.org/animal-info/info-books/sea-turtle/topic-list.htm Waller, Geoffrey, Burchett, Michael and Dando, Marc, Sea Life, A Complete Guide to the Marine Environment, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington 1996. ISBN: 1-56098-633-6 5.5 ACTIVITIES 5.5 ACTIVITIES 60 5.5 ACTIVITIES 61 5.5 ACTIVITIES 5.5.1 Animal, Vegetable or Mineral CORE ACTIVITY (a) Place the following into one of the three categories. If it is not an animal or a “vegetable” (i.e. plants or algae) then treat it as a mineral. • Mudskipper • Red mangrove • Brain coral • Elkhorn coral • Sea urchin • Sea anemone • Coral skeleton • Sponge • Zooxanthella • Phytoplankton • Sea cucumber • Sea star • Kelp • Sea grass 62 5.5 ACTIVITIES Animal Vegetable Mineral 5.5 ACTIVITIES 63 ANSWERS (a) Place the following into one of the three categories. If it is not an animal or a “vegetable” (i.e. plants or algae) then treat it as a mineral. • Mudskipper • Red mangrove • Brain coral • Elkhorn coral • Sea urchin • Sea anemone • Coral skeleton • Sponge • Zooxanthella • Phytoplankton • Sea cucumber • Sea star • Kelp • Sea grass 64 5.5 ACTIVITIES Animal Vegetable Mineral Mudskipper Brain coral Elkhorn coral Sea urchin Sea anemone Sponge Sea cucumber Sea star Red mangrove Zooxanthella Phytoplankton Kelp Sea grass Coral skeleton 5.5 ACTIVITIES 65 5.5.2 Coral Reef Log EXTENDED ACTIVITY If it is practicable and safe to do so, organize an excursion where pupils can swim or snorkel near a reef. Have each student keep a log of all animals and plants seen while swimming or snorkelling. Use a page for each organism. Look up the organism using a field guide or use the Web, place it into its appropriate group (animal/plant, vertebrate/invertebrate, etc.) and keep short notes about each organism’s features. Include a drawing or photo of the organism. 5.5 ACTIVITIES SAMPLE TABLE OF CONTENTS Animals Vertebrates • Fishes • Birds • Reptiles (iguanas, alligators, snakes) • Amphibians • Mammals Invertebrates • Molluscs (clams) • Echinoderms (sea stars, sea urchins) • Crustaceans (shrimps, crabs, lobsters) • Cnidarians (sea anemones) Plants Grasses •… •… •… Flowering Plants •… •… •… 66 5.5 ACTIVITIES 5.5.3 Coral Identification CORE ACTIVITY (a) Identify the following corals and sponges by drawing an arrow between the label and animal: (b) Which of the illustrated corals are hard corals? (c) Which of the illustrated corals are soft corals? 67 5.5 ACTIVITIES ANSWERS (a) Identify the following corals and sponges by drawing an arrow between the label and animal: (b) Which of the illustrated corals are hard corals? Brain Coral, Elkhorn Coral and Staghorn Coral (c) Which of the illustrated corals are soft corals? Sea Fan 68 5.5 ACTIVITIES 5.5.4 Reef Fish Identification CORE ACTIVITY (a) What are some of the differences between bony and cartilaginous fishes? (b) Write the name of the following fishes under its picture. • French angelfish • Sandbar shark • Blackedge moral eel • Southern stingray • Foureye butterflyfish • Blue parrotfish • Nurse shark • Tarpon • Queen triggerfish 69 5.5 ACTIVITIES (c) Which of the illustrated fishes are bony fishes? (d) Which of the illustrated fishes are cartilaginous fishes? 70 5.5 ACTIVITIES ANSWERS (a) What are some of the differences between bony and cartilaginous fishes? Bony fishes • Skeletons made of bone • Cycloid (round), ctenoid (comb-like) or ganoid (diamond-shaped) scales • A pair of gill covers • Most bony fish also have swim bladders to control their buoyancy Cartilaginous fishes • Skeletons primarily made of cartilage • Most have sharp, placoid (plate shaped) scales covering their skins • Cartilaginous fishes have no gill covers • No or swim bladders and use large, oil-filled livers to help keep them buoyant (b) Write the name of the following fishes under its picture. • French angelfish • Sandbar shark • Blackedge moral eel • Southern stingray • Foureye butterflyfish • Blue parrotfish • Nurse shark • Tarpon • Queen triggerfish 71 5.5 ACTIVITIES 72 (c) Which of the illustrated fishes are bony fishes? French angelfish, foureye butterflyfish, blackedge moray eel, blue parrotfish, queen triggerfish, and tarpon (d) Which of the illustrated fishes are cartilaginous fishes? Nurse shark, sandbar shark, southern stingray 5.5 ACTIVITIES 5.5.5 Sea Turtles CORE ACTIVITY (a) Colour in the green turtle dark brown or olive and add the following labels to the picture: • Eye • Nuchal – large scute at the front of the turtles carapace by the neck • Claw • Tail • Flipper • Central scute • Costal (side) scute • Marginal (edge) scute • Nostril 73 5.5 ACTIVITIES 74 5.5 ACTIVITIES (b) Write a brief description of sea turtles (c) Which is the largest sea turtle? How long do sea turtles live? (d) What do sea turtles eat? (e) How do sea turtles reproduce? (f) Why do most turtles never make it to adulthood? (g) What is the “arribada”? (h) Why are Green turtles brown? (i) Where are sea turtles found? (j) What is the status of sea turtles? 75 5.5 ACTIVITIES ANSWERS (a) Colour in the green turtle dark brown or olive and add the following labels to the picture: • Eye • Nuchal – large scute at the front of the turtles carapace by the neck • Claw • Tail • Flipper • Central scute • Costal (side) scute • Marginal (edge) scute • Nostril 76 5.5 ACTIVITIES 77 5.5 ACTIVITIES 78 (b) Write a brief description of sea turtles Sea turtles are reptiles that are part of the turtle and tortoise order. A sea turtle’s body is partially covered by a shell. This shell consists of two parts; an upper carapace and a lower plastron. Unlike other turtles, a sea turtle’s head & flippers cannot be pulled inside of its shell. There are 7 species of sea turtle: Green, Loggerhead, Hawksbill, Flatback, Kemp’s Ridley, Olive Ridley & Leatherback. All species have shells with horny scales (“scutes”) except the Leatherback which is covered with leathery skin. (c) Which is the largest sea turtle? How long do sea turtles live? The largest sea turtle is the Leatherback, which grows to about 64” in length and can weigh 1300 lbs. Sea turtles can possibly live over 100 years depending on species. The following outlines the weight and average carapace length of the sea turtles: (d) What do sea turtles eat? Sea turtles feed on a variety of items including turtle grass, jellyfish, sponges, fish and crustaceans. (e) How do sea turtles reproduce? Female sea turtles come ashore to lay her eggs. The female digs a burrow with her hind legs, lays a batch of eggs and covers them with sand. Sand temperature determines the sex of the hatchling; warmer -> females; cooler -> males. Hatchlings dig their way out of the burrow and head for the sea. 5.5 ACTIVITIES 79 (f) Why do most turtles never make it to adulthood? Hatchlings and young turtles are preyed upon by many predators (e.g. raccoons, crabs, foxes, sea birds and large fish). Sea turtles are hunted by humans for meat, eggs, skin and shells to produce face cream, cosmetics and souvenirs. Habitat destruction has also drastically reduced the number of available beaches for breeding. As a result, only 1% of sea turtle eggs will make it to adulthood. (g) What is the “arribada”? All sea turtles have solitary nesting except the Ridleys. The Ridleys arrive and nest as a mass. This is called the “arribada” or the “arrival” in Spanish. (h) Why are Green turtles brown? The Green turtle is named for its green body fat (“calipee”) not its carapace color. Calipee is used in making turtle soup. (i) Where are sea turtles found? Sea turtles are found in many of the world’s oceans including the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian oceans. (j) What is the status of sea turtles? All sea turtles are either endangered or threatened. Sea turtles are protected in the USA under the Endangered Species Act and around the world by CITES (Convention on the International Trade of Endangered Species of Flora and Fauna).