The Labor Participation – Fertility Trade

The Labor Participation – Fertility Trade-off:

Exploring Fecundity and its Consequences to Women’s Employment in the

Philippines

Ariane Gabrielle C. Lim, Kenneth S. Santos and Daphne Ashley L. Sze ariane_lim@dlsu.ph, kenneth_santos@dlsu.ph, daphne_sze@dlsu.ph

De La Salle University

Abstract

As women are now given more freedom and choice to pursue employment, the world’s over-all fertility has been decreasing mainly due to the shift in time allocation between working and childrearing. As such, we study the case of the Philippines, where there exists a decreasing fertility rate and increasing openness for women labor participation. We focused on the distinction between fertility and fecundity, the former being the manifestation of the latter and aim to trace and compare the effects of both fecundity and fertility to women’s employment status through the estimation of the reproduction function and multinomial logistic function. Findings suggest that the perception of women regarding employment opportunities in the Philippines links the negative relationship observed between fertility, fecundity and women’s employment status. Today, there has been a convergence in the traditional family roles of men and women, as both genders now have identical employment opportunities that continue to shape their preferences.

Keywords: Multinomial Logistic Function, Tobit, Fertility, Women Employment Status, Fecundity

JEL: J01, J13, J21, J22, J16

1

I. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Background of the Study

The second half of the twentieth century marked an era of women in the workplace. Although women in the workforce has been growing in number, Esping-Anderson (2002) states that employers rationally prefer men as compared to their equally capable female counter parts, because of the expected decline in the productivity of women as a result of childbirth. Although deemed to be suboptimal for the firm, previous studies regarding the effects of maternal employment on child development have shown that daughters of employed mothers have attained higher success in terms of career and education (Alessandri, 1992). In addition, children of employed mothers achieve higher cognitive scores and socio-emotional indices (Vandell & Ramanan, 1992).

However, one of the challenges of this Republic Act is the sustainability and translation of this bill into action. Considering the fact that the Philippines has a relatively high fertility of 3.1 births per woman, and a population growth rate of 2% (World Bank, 2010), the aforementioned notion makes the materialization of the Magna Carta for Women more difficult.

The country’s demographic data prompted the Philippine Senate to pass the Reproductive

Health (RH) Act, which aims to increase awareness of family planning and decrease unwanted pregnancies. To emphasize objectivity, it would be important to note that out paper is making a neutral stand on the recent passage of the RH Act.

Although the effect of fertility to the employment status has already been established in previous studies 1 , a bisection of population growth still calls for extensive research. Fecundity, which pertains to the potential capacity of a woman to bear children , is a constituent of fertility, which is the actual number of children that the woman has born . A comprehensive study about fecundity might be able to give different insights regarding issues of maternal employment and time allocation between work and home.

1.2. Research Problem

Fertility and fecundity have not yet been distinguished concerning their effect on the employment status of women in the Philippines. However, it has been observed that women with higher levels of fecundity tend to have increased usage of more effective contraceptive methods.

Thus, we hypothesize opposing effects on the two variables. Increased fertility would yield a decrease in women’s employment status, which is in accordance with the theoretical assumption that fertility and women’s employment status are negatively correlated. Decreased fecundity would yield increase

1 Though the relationship of fertility and labor market participation will still vary per country depending on prevalent cultural views.

2

in women’s employment status due to higher usage of contraception and lesser children. In line with this, we want to estimate the extent to which a woman’s biological capacity to bear children influences her employment status, to find a solution to our problem,

“How does the fecundity of a woman affect her employment status?”

1.3. Research Objectives

To derive fecundity, the exogenous variation in fertility, from the

reproduction function

To trace the effect of fertility to the employment status of women

To trace the effect of fecundity to the employment status of women

To compare the difference in the impact of fecundity and fertility to women’s employment status

1.4. Significance of the Study

Traditional belief systems have led to the segregation of roles between men and women.

Women, usually being associated with child rearing, have also been perceived as homemakers and are not usually linked with labor market activities as opposed to men. Previous studies, however, have concluded that maternal employment is beneficial for child development, which could translate into a more efficient work force for the country in the future. However, studies also suggest that private firms are reluctant to hire women due to the expected decrease in productivity brought about by childbirth; thus, the country’s realization of maternal employment benefits to child development may not be as profound.

Although the Philippines has already passed laws regarding discrimination and population control, the notion of sub-optimality of women in the workplace may be a hindrance to the materialization of such. Thus, we explore the effects of fertility to the employment status of women.

The results of this study would lead to better understanding of women and women empowerment— prompting government officials to provide policies to address such issues. In addition, the results of this study could be a basis for proper action regarding the materialization of the Magna Carta for

Women

Fecundity, although different from fertility by definition, is yet to be employed as the main subject of numerous demographic studies. The exploration of its implications and applications in the

Philippine setting would be the first of its kind and would yield meaningful insight. The differentiation of fertility and fecundity will allow for the expansion of studies regarding the demographic variable.

3

1.5. Scope and Limitation

We will do a simulation of a woman’s probability in each employment status based on quantitative data, and will determine the contemporaneous effect of the aforementioned variables using a multinomial logistic regression. The bulk of the study will concentrate on fecundity and other socio-economic variables, which are crucial to the examination of trends and the effect of the chosen variables to the employment status of a Filipina woman. Although we take into consideration factors such as age, number of children, education status, wealth, residence and type of occupation, the involvement of bargaining power in this study is not evident. As bargaining power is inflicted by societal culture and values, the omission of this factor in decision making will allow the study to become more generally acceptable to Philippine households. In addition, as we focus mainly on the

Philippines, the analysis may not be applicable to other countries. One of the major limitations of the study is that working habits and culture vary per country, the findings may only be relevant and applicable to the Philippine setting, because the data is specific to the Philippines. Second, the study is limited to the availability of data. Proxy variables will be used to capture the characteristics of the absent data variables (i.e. wealth index for wealth). In addition, observations gathered are limited to married women who are capable of having their own families. Third, measurement errors may arise from the survey process itself, from the encoding to the tabulation of results. Finally, inconsistencies in terms of concepts by the interviewees may arise leading to a misunderstanding of the questionnaire.

Despite these limitations, we will be examining the trends of the effect of various labor participation determinants over time, concentrating on fecundity and other socio-economic variables.

II. REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE

2.1. The Fertility Transition

The onset of economic growth in the modern era resulted in a rapid decline in fertility across developing countries, most noted in the last quarter of the twentieth century (Schultz, 2009).

Economic frameworks have been developed to explain this fertility transition, and one of the central themes is the demographic transition model. The demographic transition model is a sequence of developments in the population patterned after trends in fertility and mortality across time. It describes the movements from high levels of fertility and mortality rates to an eventual descend on their corresponding levels. According to Galor (2010), the overwhelming increase in the global population after the nineteenth century, brought about by developments in food production (agriculture) and public health (which reduced mortality rates), has already been reversed. This reversal explains the significant decrease in fertility and population growth across nations. Notably, it has been recognized

4

that fertility is also an outcome associated to a household decision. Thus, insights on the role of household demand on fertility have been considered relevant in the discussion of historical fertility transition (Schultz, 2009).

2.2

Determinants of Women’s Employment Status

The decision of women to enter the labor force depends on a number of factors that are constituted by characteristics of the household. The determinants below simultaneously affect the probability of a woman entering the labor force and must then be discussed for a clearer understanding of the topic.

2.2.1. Time Allocation and Opportunity Cost

The challenges of fertility decline are brought about by many key factors, one of which is the shift in the roles of couples from marriage to parenthood. Lundberg (2005) stated that parenthood implies a “crystallization of gender roles” wherein females devote more time to child care even opting to exit the labor market instead while males tend to increase the time they devote to paid work (Anxo et.al, 2007). Furthermore, Lundberg & Rose (1999) stressed that if women have comparative advantage in the provision in commodity production (i.e. home-making) and men have comparative advantage in earning as market inputs, then family utility will be maximized if specialization in household time allocation takes place.

In line with this, Becker (1985) argued that an increase in fertility will most likely change time distribution in the family, consequently influencing the wife and husband’s labor participation in terms of labor hours and earnings. Given this, Becker expressed that members who are more efficient in market activites would allocate less time for consumption activities than other family members, to enable themselves to spend more time in market activities. Generally, time allocation of an individual is affected by the opportunities open to other members of the household (Becker, 1965).

In relation to the Becker’s (1965) claim, Matysiak (2011) added that demand for children is inversely related to cost. There are direct and indirect cost of children, wherein opportunity costs refer to the value of time parents invest in childrearing, of which the mother’s wage and value of human capital forgoes promotion and work potential. In addition to this, Matysiak (2011) considers the two effects of childrearing, the income and price effect. The income effect refers to the positive relationship of household income to the number of children, while the price effect refers to the phenomena wherein employed women incur higher opportunity cost that women who do not work.

Moreover, a woman will only take the job if her reservation wage exceeds that of the value of her time spent at home (Matysiak, 2011). Reservation wage for mothers with younger children are expected to

5

be higher than that with no children or that with grown up children, implying that the income effect eventually compensates for the price effect as the child ages, the mother has a higher probability of entering the labor market (Matysiak, 2011).

2.2.2. Household Wealth and Labor Force Participation

Household decisions regarding labor force participation do not rest solely on household income and bargaining power, as it includes the socio-economic concept of wealth. Pecuniary measures of wealth, or economic well-being in general, discounts the effect of other crucial factors that determine the welfare of a household. According to Wolff (2006), the level of economic well-being is substantially affected when income (a pecuniary measure) is adjusted for wealth determinants.

Previous studies that relate wealth to a household’s decision to participate in the labor force have interesting results. Kalwij (1998) established the observation that labor decisions in the household can be affected by wealth via the concept of reservation wage. According to his study, a higher wealth level increases the reservation wage, thus decreasing the probability of a household member entering the labor force. His results however, showed that this theory is insignificant when households take into account the financial consequences of having children.

2.2.3. Age and Income

Majority of the inputs into the labor market of any economy come from its own households.

The importance of this minute unit of society cannot be discounted, as it is from within and between the interactions of these households our labor market come into place. Accordingly, Schultz (2010) stated that family-coordinated productive behaviours, such as labor participation, may be determined by changes in fertility and age composition at the household level, and both cannot be treated as exogenous causes for anticipated changes in the labor market. In addition, Hafeez & Ahmad (2002) found evidence that younger females cannot command a decent wage due to lack of experience and training, implying that probability of female labor force participation increases with age. Emphasizing that women Labor Force Participation (LFP) is inversely related and strongly influenced by monthly income of the family, the estimation result of Hafeez & Ahmad (2002) suggests an increase in household income reduces the probability of women participation in the labor force. Thus, women in wealthy families participate less in the labor force.

As income and wealth are not the only factor affecting the decision of the household to produce more children, education comes into place as it is inter-related with the household’s employment opportunities. At the same time, with more years of educational attainment, parents tend to be more

6

conscious of their fertility behaviour, as their primary goal is quality of life over quantity of children

(Hafeez & Ahmad, 2002).

2.2.4. Number of Children and Education

Female labor participation on the other hand, is primarily affected by fertility, that is, women who have fewer children are more readily available to participate in the labor market given that they have essentially more time. This relationship can however be affected by a female’s educational level, the quantity versus quality of children trade-off, and the disparities in wage level across genders

(Chenery et. al, 2010). Jaumotte (2003) emphasized the role of children to female labor supply by reiterating that children increase the elasticity of female labor supply relative to market wage, as this provides more opportunities for home production.

Aside from improving a woman’s employability and competitiveness in the labor market, according to Cheng (1999) and Schultz (1997), education and wages enhance a woman’s participation in economic activities outside home while negatively affecting her fertility, resulting to a smaller desired family size. This means that women with higher level of education generally lean toward a reduced level of fertility, notwithstanding other cultural and biological factors that may affect it.

Further strengthening the claim of Cheng (1999), Hafeez & Ahmad (2002) affirmed that an increase in the level of education increases probability of participation, reinforcing the attachment of women to the labor market by increasing potential earning and “reducing the scope of specialization within the couple”.

2.2.5. Socio-Cultural Factors

Notably, studies have concluded that programs on women education, child health and nutrition, as well as family planning methods added to the decrease in fertility rate, child mortality and population growth in developing countries. This macro-context highly depends on culture, societal opportunities, values and other structural impositions that define the environment and the labor market

(Matysiak, 2011).

Culture is said to play an important role in economics, but is however overlooked because skeptics argue that culture is too broad to capture; therefore, it is usually ignored by modern economics (Fernandez, 2006). In the Philippine context, Filipinos usually have close family-ties, which means that the self-concept and identities are rooted in the family. Important decisions are also discussed with the immediate family before they are made (Shapiro). In addition to being familycentric, according to Chhachii (1986) as cited in Rodriguez (n.d.), the Philippine society is also

7

patriarchal in three areas, namely - sexuality, women’s participation in the labor force and patriarchal ideology. In recent times, the role of the Filipino woman in the family has been changing drastically.

According to Carandang (2008), the majority of women are now participating actively in the labor force and now hold jobs outside the household. A number of them are also considered to be the main or only breadwinners of the family. Furthermore, Prasetya (n.d.) confirmed that the support of the husband to the wife’s career is correlated to her marital satisfaction. Women in a family seek selfconcept and independence while, at the same time, seeking the approval of their husbands.

2.3. The Concept of Fecundity

2.3.1. Contextual Distinction of Fecundity and Fertility

As used in the study of Kim & Aasve (2006), fecundity refers to the measure of an individual’s potential capacity to produce children, irrespective of the actuality of production.

In demographics, it is distinguished from fertility by actual birth performance (Spiegelman,

1968) . In other words, fecundity is the potential reproductive capacity while fertility can be considered as the manifestation of fecundity (Pressat, 2008), usually determined by childbirth. We can also look at fecundity as a limit to one’s fertility, in that it is a biological constraint present in all men and women. It is noted however, that men have a longer fecundity horizon than women (Polachek, 2011).

Fecundity has been also considered as a representation of the exogenous variation in birth supply (Chenery et. al, 2010), since it is a factor of fertility beyond the couple’s control. According to

Schultz (2010), fecundity as an exogenous measure highlights the biological heterogeneity that varies across individuals, giving more structure to the reproductive process of couples. To quantify such a measure empirically using historical data might seem unlikely; however, Rosenzweig & Schultz

(1985), introduced the technology of reproduction via the reproduction function, which will be discussed at the later sections of the paper. The role of fecundity in human capital investment has also been highlighted in Rosenzweig & Schultz (1987), which posited that improvements in birth control mechanisms might increase the likelihood for parents to invest in the quality of their children, giving rise to the argument that there exists a trade-off between quality and quantity of children. The methodology applied to measure fecundity involved estimating the couples’ latent or unknown reproductive endowment (fecundity) given their contraceptive use and observable biological characteristics.

In general, it can be said that the difference between fertility and fecundity is that fertility pertains to the number of children, which are already born; while fecundity is a term coined as a measure denoting the ability of the woman to conceive. It is important to note that the difference

8

between the definitions is that an increase in fertility requires the birth of the child; whilst fecundity does not necessarily require it.

2.3.2. The Reproduction Function

Using the reproduction function as means to estimate the effect of the exogenous fertility supply on human capital investment, Rosenzweig & Schultz (1985) employed different strategies to determine the effect of the couple’s choice of fertility to levels of human capital investments. In addition, instrumental variables were used to account for the endogeneity and correlation between fertility and the error term in the demand equation in a least square regression of human capital input against family size. Inference from the method suggests that couples with higher propensities to conceive face higher costs to control fertility leading to the fact that Malaysians cannot fully eradicate the influence of the exogenous supply of birth to the actual cumulating of births. It was then concluded that Malaysian couples alter the usage and selection of contraceptive methods in response to their exogenous supply of birth (Rosenzweig & Schultz, 1985).

2.4. Research Gap

Literature gathered imply that the conventional expectations regarding the correlation of labor market outcomes with respect to the existence of children appear to be different depending on the assumptions made in a given study, in that, declines in labor participation cannot be solely attributed to specialization of household role. Given this, there are notable research gaps found on the gathered literature: first, the use of fecundity in demographic studies has not yet been distinguished from the results that fertility yields when regressed against the labor participation rate. Therefore, we would like to explore more on these factors, which have not been further explained in the literature. Second, culture as a factor of labor participation has never been explored, as there is a lack of qualitative measures for such an attribute. Although there are several aspects of culture, it has never been considered as a factor affecting labor participation, which must be reconsidered as it affects society’s perception and in turn, household perception about labor force participation. Third, the method employed in previous studies such as Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) is found to be prone to endogeneity problem as correlation exists between the error term and the independent variables, which violates the Classicial Linear Regression Model (CLRM) assumption of exogeneity.

9

III. Conceptual Framework

3.1 Neoclassical Theory of Labor Supply

The Neoclassical Theory of Labor Supply in Cahuc & Zylbreberg (2004) assumes that: (1) there are only two possible uses of time: labor and leisure; (2) each individual selects the combination of hours of work and leisure that maximizes his level of utility. For individuals who work, opportunity cost of an additional hour of leisure is the wage rate. An individual who does not participate in market activities will only join market activities if and only if real wage exceeds the reservation wage, otherwise the individual will choose to not participate in labor market activities. This is particularly true to mothers who are part of the labor force as reservation wage for mothers with young children are always higher that mothers without children (Matysiak, 2011).

3.1.1 Labor Participation – Fertility Trade Off

The work-fertility trade off is a deviation patterned from the Neoclassical Theory of Labor

Supply that highlights the role of children in determining a woman’s labor participation decision. The

Neoclassical Theory of Labor Supply supports the Becker (1965) Time Allocation Model, where it also focuses on time as the main constraint. As the role of parents become more diverse, time has become compromised amidst the presence of labor force participation and childrearing

3.2 Theory of the Allocation of Time

The theory of time allocation by Becker (1965) stresses that the allocation of time between various activities rests on the assumption that the household is both a producer and a consumer. It produces commodities with two inputs—time and goods, which are then subject to the traditional costminimization of the theory of the firm. The household then produces the number of commodities, which will maximize its utility subjected to the prices and availability of resources. The theory focused on the issue between family size and income, traditionally, is viewed to have a negative correlation—an increase in income leads to a reduction in the number of children per family. However, economic theory suggests a positive relationship between income and family size holding birth control knowledge and other variables constant. Becker (1965) therefore asserted that the negative correlation of family size and income stems from the fact there indeed exist a positive relationship between income, knowledge and other variables.

10

3.3. Microeconomic Theory of Fertility

The Becker (1965) model implies that the reallocation of time entails a coexistent reallocation of goods and time; thus, making the two decisions interrelated. It is assumed that the objective of the family is to maximize its utility function given its limited capacity to produce Z commodities. The demand functions for the number of children, child quality and standard of living are a result of maximizing the family’s utility function with the real lifetime consumption constraint. This means that there must be a balance of satisfaction received from children and sources not related to children (which is denoted by the standard of living). In addition, the family must also decide whether to invest in the quality or quantity of the children, in which a multiplicative relationship exists. Speculated by Becker

(1960), as cited in Willis, 1979), positive wealth elasticities denotes a substantially higher elasticity of quality (of children) relative to that of quantity.

3.4 Technology of Birth Production

Pioneered by Rosenzweig & Schultz (1985), the technology of birth production describes the role of a couple’s contraceptive behavior, number of past realized births, and a woman’s age to her actual birth production capacity, known as the conception rate. It represents the realization of the observed childbearing behavior of a couple at a certain point in time, wherein conception is assumed to be a stochastic process beyond the couple’s control (Hotz, Klerman, & Willis, n.d.) The technology of birth production, also known as the reproduction function, is represented mathematically as:

N jt

Z jt

X jt

jt

j

3.1

Where it is assumed that N j,t or the conception rate of individual j at time t, can be reduced by the presence of fertility control inputs βZ j,t and a woman’s biological characteristics γX j,t

.

The efficacy of birth control is the denoted by the coefficient

β.

Fecundity, or the potential ability of an individual to reproduce is the sum of exogenous terms, ε j,t and μ j

, . The reproduction function enables the determination of individual-specific measures of both the random and persistent components of fecundity through an approximation of the exogenous variations in fertility. An important assumption in this model is that the relationship between variations in fertility, also known as fecundity, with respect to the use of contraception depends on whether past cumulative births is due to couple’s preferences. If a conception is unanticipated, the relationship is known to be positive as long as the savings from an averted conception in the future will be more than the cost of contraception today (Rosenzweig &

Schultz, 1985). Thus, we can say that an unanticipated conception at time t-1

increases the likelihood of contraceptive use at time t.

Therefore, it can be said that women with higher levels of fecundity tend to use more effective contraceptive techniques.

11

IV. METHODOLOGY

4.1. Model Description

To operationalize the study, we source cross sectional data from the National Demographic and

Health Survey (NDHS), which contain the appropriate variables and proxies that embodies the aspect we wish to capture. These cross-section variables for 2008 will be utilized to construct a model that will establish the relationship between determinant-variables and women employment status.

Previous research has suggested the use of different methods to exhibit the relationship such as the Tobit regression, instrumental variables and ordinary least squares. However, these methods would be deemed inappropriate for the extent of our study as there will only be three acceptable outcomes for our model: full-time workers, part-time workers, and no occupation. This would entail the use of the multinomial logistic regression in order to assess the weights of the respective variables to the probability of the woman’s employment status.

4.2. Model Specification

Previous studies have suggested that a relationship exists between employment status, fertility and its determinants. Generally, the relationship assumed is as follows:

EMPST i j

( ij

, X i j

, V i j

)

CEPTR ij

( ij

, ij

, Z i j

, X ij

)

4.1

4.2

Equation (4.1) is a structural equation, which captures the relationship between employment status and its determinants. Note that it has an endogenous right hand side variable, CEPTR i,

which is the specification for the reproduction technology, given by Equation (4.2). The identification of this relationship mainly stems from the theoretical assumptions proposed by Rosenzweig & Schultz,

(1985) Kim & Aasve (2006) and Becker (1965).

4.3. Estimation of the Reproduction Function

We first estimate the reproduction function to obtain the fixed and random components of fecundity, which will be used as an exogenous variable in our employment status model. Equation 4.4 denotes the general specification of the reproduction function, adopted from the studies of Rosenzweig

& Schultz (1987) and Kim & Aassve (2006). It assumes a linear relationship between conception rate and its various determinants, which include the observable biological characteristics of the sample and their contraceptive behaviour. In passing, note that the conception rate is derived from the ratio of the number of months at risk of pregnancy with respect to the number of births prior to the latest survey period (Kim & Aasve, 2006). From the Philippine Demographic and Health Survey (DHS), we will use data on the respondents’ preceding birth interval, defined as the difference in months of the most

12

recent birth and the previous birth. Another apparatus to the measure of conception rate is the Total

Number of Births in the last five years prior to the interview. The mathematical representation of the computation is denoted by Equation 4.3.

CEPTR

i j

TNLB

i j

PBIV

i j

4.3

Where,

CEPTR it

= Conception rate of the i th

observation at survey period t;

PBIV it

= Preceding birth interval in months of the i th

observation at survey

period t;

TNLB it

= Total number of births since the last survey period.

Fecundity has been associated with the use of contraception. The convention is that, higher levels of fecundity lead to the use of more effective contraceptive methods. From this illustration, we can take note of various causal interrelationships that exist in our reproduction function. First, by its contextual definition, fecundity can be associated with the number of past realized births which in our model is represented by conception rate. Second, the choice of contraceptive methods is deemed to be correlated with fecundity, which is in turn a determinant of our endogenous left hand side variable

(Kim & Aassve, 2006). Alternatively, we can say that the model violates the exogeneity assumption of the Classical Linear Regression Model (CLRM), thus rendering our estimates to be biased and inconsistent. This violation stems from the existence of the simultaneous causality bias and the selection bias.

Theoretically, the simultaneous causality bias occurs when there are endogenous explanatory variables in the model. This can also be referred to as instantaneous causation of our dependent variable on the regressors. According to Apel (2009), the effect of the bias is dependent on the sign of the causation of the dependent variable on the regressor, such that if positive, the coefficients are said to be overestimated values of the true effect, whereas if negative, the coefficients are said to be underestimated. On the other hand, the selection bias is akin to the omitted variable bias where the model fails to account for the unobserved effects of other random variables to the regressand, wherein the coefficients in the model absorb the indirect effect of the omitted variables, which lead to improper estimation (Apel, 2009). Due to the aforementioned limitations that our model is assumed to suffer, we cannot properly estimate our reproduction function using the Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) technique.

13

4.3.1 Tobit Regression

In addition to the shortcomings of the basic OLS model, Rosenzweig & Schultz (1985) have observed that conceptions tend to be truncated to zero , that is most couples do not exhibit a successful conception over the survey period. For this reason, we adopt the Tobit regression model to account for this observation. Given the two estimation techniques, the study assumes that the Tobit model gives the most efficient estimates of the reproduction function due to the truncation in data.

However, the OLS gives the research a means for comparative analysis in determining the effects of contraceptive use on fertility.

The reproduction function specification used in this study is as follows:

CEPTR ij

0

1

WOAGE ij

2

PILLS ij

3

CRIUD ij

4

CNDOM ij

5

STERL ij

6

INEFF i j

7

NMBER i j

8

WOAGE

2 i j

i j

4.4

4.4. Fixed and Random Components of Fecundity

After running the Tobit regression to estimate the reproduction function, we now obtain the fixed and random component of fecundity, known as ij

and jt

from Equation 4.5 and Equation 4.6 respectively,

j

T

0

N jt

Njt

T

jt

N

jt

N

jt

j

4.5

4.6

Wherein

N

ˆ

jt refers to the estimated conception rate from Equation 4.4; and T refers to a period of five years which is the difference between two time periods of the survey, measured in months. Obtained values for ij

and jt

will now be used as predetermined regressors in the succeeding regressions. The last step is to regress the predetermined variables against the dependent variable, women’s employment status to obtain estimates that will explain and establish the relationship between the employment status of women and its determinants.

4.5. The Multinomial Logistic Model

Multinomial logistic model is used to analyze the choice of an individual among a set of J alternatives, in this case, women’s preference on part-time or full-time job and being unemployed,

14

given the demands of motherhood. Multinomial logistic models focus on the individual as the unit of analysis and use the individual’s characteristics such as age, education and wealth as explanatory variables. The general formulation of the model is as follows (Hoffman & Duncan, 1988)

P

ij

exp(

X

i

j

) k j

1

X

i k

4.7

Where X i

stands for the characteristics of individual i , and Z i for the characteristics of the j th alternative for individual I

, with the corresponding parameter vectors denoted by β; let

J be the number of unordered alternatives, and Pi , the probability that individual i chooses alternative j . Furthermore, in a multinomial logistic model, the characteristics of the individuals (exogenous variables) are the constraint across the alternatives. The effect of the X i

variables on the probability of choosing each alternative, relative to the benchmark alternative is reflected in the estimated coefficients.

Applying the model to this paper, we derive the following equations,

EMPST ij

6

0

RANDM i j

1

WOAGE ij

7

TYRES

2

WEDUC ij

8

EDRND ij

3

HUAGE ij

9

WLRND ij

4

HEDUC ij

10

AGRND ij

5

WEALT ij

11

AGRIR

ij

12

MANUR

ij

13

SERVR

ij

14

HUAGE

2

15

WOAGE

2 i j

EMPST ij

0

1

WOAGE ij

6

FIXED i j

7

TYRES

2

WEDUC ij

8

EDFIX ij

3

HUAGE ij

9

WLFIX ij

4

HEDUC ij

10

AGFIX ij

11

AGRIX

ij

12

MANUX

ij

13

SERVX

ij

14

HUAGE

2

5

WEALT ij

15

WOAGE

2 i j

EMPST ij

0

1

WOAGE ij

6

CEPTR i j

7

TYRES

2

WEDUC ij

8

EDFRT ij

3

HUAGE ij

9

WELFT ij

4

HEDUC ij

10

AGEFT ij

5

WEALT ij

11

AGRIF

ij

12

MANUF

ij

13

SERVF

ij

14

HUAGE

2

15

WOAGE

2 i j

4.8

4.9

4.10

Here, EMPST ij refers to the employment status, with nominal values, 0 being the unemployed, 1 for part-time, and 2 for full time workers. The independent variables are demographic and fertility determinants, along with interaction variables with fertility, such as EDFRT ij

, WELFT ij

, and AGEFT ij

, along with employment interaction variables that capture the relationship between fertility/fecundity and the three main industry sectors as seen in AGRIF ij

, MANUF ij

, and SERVF ij

.

15

V. PRESENTATION OF RESULTS AND ANALYSIS

5.1 Descriptive Statistics

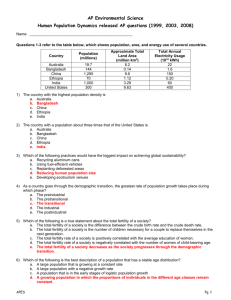

The National Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS) collected 23,248 observations using cross sectional data for the year 2008. The said treated dataset are only limited to wives and mothers to encapsulate the behavior of the variables in the model. Below are the summary statistics of the said data set.

Table 5.1. Summary Statistics of the Demographic Profiles of NDHS

Women’s Education (in years)

Women’s Age (in years)

Number of Children (in

NDHS 2008

Mean

8.750817

7.775895

41.42541

37.94898

5.037423

-267.3125

Min

0

0

18

15

1

-2156.07

Max

25

17

80

49

16

2079.40

Source: Authors’ calculations

Generally, women take roughly 9 years of schooling. This translates to women mostly finishing high school; while men have an average of 8 schooling years. Second, women have a mean age of 38 years old, while their partners has a mean age of 41 years old. Third, families have at least 1

– 16 children at home, with 5 as the mean number of children. This is indicative of the growing youth population of the Philippines. Finally, wealth here is not an absolute measure, as this is only an index of measurement; from the dataset gathered a mean of -267.3125 indicates that most households interviewed were the poor, with a range of -2156.07 to 2079.40. The wealth factor determines the ability of a household to sustain itself, given the combined earnings of the family; thus, a poor household would imply that needs are not met, and basic needs are prioritized.

Table 5.2. Summary Statistics of Women’s Employment Status for NDHS

Unemployed

Part-Time

Full-Time

NDHS 2008

Frequency

8324

4990

9934

Percentage

35.81

21.46

42.73

16

Source: Authors’ calculations

Roughly 36% are currently unemployed and approximately 21% of the women interviewed worked seasonally and occasional combined to form the part-time 2 workers. Conclusively, about 43% of the sample is engaged actively in the labor market.

3

Table 5.3. Summary Statistics of Contraceptive Usage for NDHS (2008)

NDHS 2008 (in terms of women using)

Pills

Condom

IUD

Sterilization

Ineffective

Methods

Frequency

3335

469

2877

4648

10942

Source: Authors’ calculations

977

Percentage

14.35

2.02

4.20

12.38

19.99

47.07

We find that for both survey periods, majority of couples do not use any form of contraception.

On the other hand, couples using contraceptive techniques prefer ineffective methods with 20% of the respondents claiming to do so. Ineffective methods include rhythm, calendar, and withdrawal methods whose efficiency are deemed low based on standard observations. The number of women who claimed that they, or their husbands have been sterilized is at almost 12% by 2008.

4 The use of pills for women is at 14%, which is relatively higher compared to those who claimed to have been using condoms.

Only 2.02% of respondents claim to use condoms in 2008.

5

5.2 Regression Results and Analysis

5.2.1 Estimates of the Reproduction Function

Table 5.4 presents the results from the estimation of the reproduction function. The ordinary least squares estimates show that contraceptive use is negatively correlated with conception rate.

Together with the other demographic variables such as age and number of children, the model explains

34.6% of conception rate. The Tobit estimates report significant and negative relationships between

2 Part-time jobs are defined as jobs wherein workers do not complete the average working time of 8 hours a day it may depend on the seasonal availability such as an overseas offer, agricultural jobs and the likes.

3 These women work 8 or more hours a day, with stable income.

4 . These couples therefore do not prefer to have any more children as the effects of female or male sterilization is permanent.

5

This may be attributed to the high cost of using condoms as compared to other methods. Aside from the cost, condoms are also disposable after use.

17

contraceptive methods and conception rates except the use of ineffective methods. This implies that an individual’s conception rate can increase when preference for ineffective methods exist. Another note is that the use of condoms as a contraceptive technique is neither efficient nor significant, as indicated.

Noted here are the coefficients of the Tobit estimates which contains coefficients that project a larger magnitude. Here, the ordinary least square estimates are underestimated, as seen in Kim & Aasve

(2006).

Overall, results suggest that couples with higher “biologically-determined propensities to conceive” tend to select greater levels of fertility control. This result is in line with the analysis of

Rosenzweig & Schultz (1987) wherein realized births is dependent on both biological and stochastic factors beyond the couple’s control; as well as preferences of parents, conveyed by the use of imperfect fertility controls. Particularly, more fecund women face higher costs of controlling fertility when such control is not costless, and will experience higher realized fertility, leading to a reallocation of diminished resources across other goods Rosenzweig & Schultz (1987).

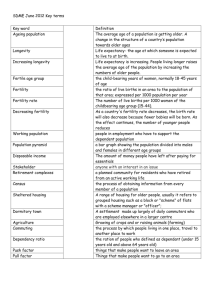

Table 5.4 Ordinary Least Squares and Tobit Specifications of the Reproduction

Function

Explanatory OLS variable:

Coefficient

Conception rate 1

Contraceptive

IUD

Sterilization

Condom

Ineffective

- 0.0081

- 0.01096

- 0.0772

- 0.0032 methods 2

Women’s Age

Women’s Age 2

0.0002

0.0072

- 0.00876

5.59e-05

Intercept

R 2

.24876

0.3491

1 Computed values of conception rate

P > |t|

0.000

0.000

0.000

0.187

0.770

0.000

0.000

0.000

0.000

Tobit Censored

Coefficient

- 0.011

- 0.0221

- 0.0213

- 0.00429

0.0031

0.015

0.00056

-0.0014

0.1096

-

2 Ineffective methods include withdrawal, periodic, patch, and other methods.

P > |t|

0.000

0.000

0.000

0.282

0.028

0.000

0.489

0.000

0.000

-

18

5.2.2 Estimates of the Multinomial Logistic Regression

Table 5.5 Marginal effects of CEPTRHAT (Fertility)

RANDOM Dependent Variable: Women’s Employment Status

WEDUC

HEDUC

HUAGE

WOAGE

WEALT

TYRES

CEPTR

EDFRT

WELFT

AGEFT

AGRIF

MANUF

SERVF

WOAGE

2

HUAGE 2

Predicted

Prob.

Part Time P-value dy/dx

.00011

-.00441

.00621

.00567

-6.09e-04

.01725

1.4436

-0.14028

1.70e-04

-.05678

1.27178

0.246

0.007

0.000

0.000

1.22179 0.000

2.13432

-8.31e-05

0.000

0.352

-5.67e-05

.20978543

0.097

0.900

0.000

0.042

0.411

0.000

0.008

0.008

Full Time P-value dy/dx

.01274

-.00813

.00391

-0.00954

6.93e-05

-.01154

-3.96361

-.03485

5.53e-04

.10690

.40486

0.017

0.000

0.000

0.015

.69958 0.008

-1.66742

-.00024

0.000

0.052

-.00041

.42577863

0.348

0.000

0.000

0.325

0.311

0.000

0.142

0.000

Table 5.5 shows the results of a multinomial logit regression, with the employment status of a woman as the dependent variable, and with demographic and interaction variables as its independent variables.

Table 5.6 Marginal effects of FIXED and RANDOM(Fecundity)

RANDOM

Dependent Variable: Women’s Employment Status

Part Full Time Part Time Full Time

WEDUC

HEDUC

HUAGE

WOAGE

WEALT

-.00070

0010598.0

-.00424

(0.002)

.00743

(0.091)

-.00684

(0.316)

-6.12e-05

(0.000) dy/dx

.011001

(0.000)

-.00539

(0.001)

.00044

(0.935)

.06784

(0.000)

9.01e-05

(0.000) dy/dx

-.00070

-.00424

(0.002)

.00743

(0.091)

-.00684

(0.316)

-6.12e-05

(0.000) dy/dx

.011001

(0.000)

-.00539

(0.001)

.00044

(0.935)

.06784

(0.000)

9.01e-05

(0.000)

19

TYRES

EDUFEC

.02417

FIXED

RANDM

(0.005)

-9.7894

Interaction variables

(0.000)

-.05659

(0.583)

WELFEC 0.00015

(0.780)

AGEFEC .07570

AGRIFEC

(0.245)

17.2471

(0.000)

MANUFE

C

SERVFEC

WOAGE 2

HUAGE 2

Predicted

19.01753

(0.000)

13.6046

(0.000)

.00003

(0.751)

-.00006

(0.187)

.24895

-.02628

(0.009)

-30.1661

(0.000)

-1.149704

(0.914)

-.000324

(0.000)

-.4542718

(0.778)

37.8578

(0.000)

38.7830

(0.000)

46.3305

(0.000)

-.00071

(0.000)

-5.66e-06

(0.992)

.43778

.02417

(0.005)

-2.4473

(0.000)

-.01415

(0.583)

0.0004

(0.780)

.01892

(0.245)

4.31178

(0.000)

4.75438

(0.000)

3.40113

(0.000)

.00003

(0.751)

-.00006

(0.187)

.24896

-.02628

(0.009)

-7.5415

(0.000)

-.00356

(0.914)

-0.0070

(0.000)

0.00608

(0.778)

9.4645

(0.000)

9.6832

(0.000)

11.5826

(0.000)

-.00071

(0.000)

5.66e-07

(0.992)

.437780

Prob.

Table 5.6 shows the results of a multinomial logistic regression, with the employment status of a woman as the dependent variable, and with demographic and interaction variables as its independent variables, together with the fixed and random components of fecundity.

Demographic variables

Women’s Education (WEDUC)

Education facilitates an increase in knowledge, and brings changes in the attitudes and values of a person. Therefore, it is not unusual that education is vital to increase women’s employment potential.

Through education, women today are not satisfied with mere housewife roles; they come to realize the importance of their existence and want to utilize their intellect to gain personal satisfaction and identity security in the family and in society (Singh et. al., 2006). The results, with women education deemed significant with an increase in probability of working full time by .01101% and 0.01274% in the presence of fecundity and fertility respectively. This is in line with Hafeez & Ahmad (2002) results affirming an increase in the level of education increases probability of participation, reinforcing the attachment of women to the labor market by increasing potential earning and “reducing the scope

20

of specialization within the couple”. In addition, the relationship between part-time employment and women’s education is insignificant, as part-time jobs do not offer competitive wage rates as that of full time jobs; therefore, higher education would not be effective in a clamor for better earnings in a parttime setting. The educational attainment of women and opportunity cost for producing the non-market output shares a positive relationship with participating in income producing activities outside the household (Hafeez & Ahmad, 2002).

Women’s Age (WOAGE and WOAGE 2 )

We include a quadratic transformation of women’s age to allow for possible non-linear relationships that exist between age and the dependent variable, women’s employment status. We find that age negatively affects the probability of working part-time and full-time, true for both the persistent and random components of fecundity. The age transformation variable showed the same effect to fecundity except that using the random component, age squared positively affects the probability of part-time work and negatively affects full time work. Women’s opportunity cost associated with employment is lower in the earlier years, as it has been established that younger women command lower wages as compared to older women. Thus, full-time employment is more viable for more fecund women who are nearing the peak of the childbearing age, as the responsibility of motherhood and providing for the family also deepens.

Type of Residence (TYRES)

The results suggest a negative effect of being in the urban setting with regards to women employment. The probability of being employed full time decreases when you reside in the urban setting and being employed part-time increases, this could imply that it is more difficult to get a full time job for women due to the increased competition in the urban areas. The urban areas of the

Philippines house the majority of the country’s population. It should also be noted that the probability of being employed part-time increases in the urban setting because urban mothers allot more time to care for their children, but at the same time, they need to contribute to the family’s income.

Husband’s Age and Education (HUAGE & HEDUC)

With respect to husbands’ age and the squared of the husbands’ age, there is an insignificant relationship between husband’s age to the probability of getting a part time employment and full time employment. This is attributed to the fact that partners’ age do not determine a woman’s employment status primarily because women would still work to finance the needs of their children regardless of their partners’ age.

21

Partners’ education, on the other hand, exhibits a negative trend relative to the employment status of women. Results show that for both part time and full time employment, the relationship of men’s education to women’s employment is highly significant. Partner’s education in relation to the probability of women working part time, decrease by .00441% and .00424% in the presence of fertility and fecundity respectively; while in relation to the probability of women working full time, a decrease of .00813% and .00539% is attributed to men’s education, in presence of fertility and fecundity respectively. The intuition behind this is that, as men’s educational attainment increases, their economic opportunities and earnings increase as well, enough to sustain household spending. An increase in family earnings would eventually lessen the working hours of their wives, and result to a reallocation of time between home and work, as stated by Becker (1965). As education is the primary driver of earnings in this country, an increase in the earnings of men would result to women working less, and focusing instead in household chores and children, thus lessening their labor force involvement.

Wealth (WEALT)

Household wealth indices for all regression results show an infinitesimally small change to the probability of both part-time and full-time employment for every increase along the index. The results show a significant effect to the probability of a woman being employed part-time or full-time. An increase in wealth would yield a decrease in part-time employment and an increase in full-time employment. The rationale behind this could be because as wealth increases, people find less reason to work part-time, confirming the result of Kalwij (1998), a higher wealth level increases the reservation wage, and decreasing the probability of women to enter the labor force. Furthermore, Goodstein

(2008) found evidence regarding the earlier withdrawal of older men from the labor force upon the increase in wealth through retirement benefits. For full-time employment, education and wealth have established a positive relationship and therefore play a big factor in full-time employment. As wealthy families have more capability to attain higher education, thus more opportunities in the labor market, this could explain the trend in the positive correlation of wealth and employment status.

Fertility (CEPTR)

Results show that fertility and women’s employment status particularly that of full-time women, observe a negative correlation. For this reason, we focus on an “income versus substitution” consideration as cited in Matysiak (2011). The two effects of childrearing, the income and price effect.

The income effect refers to the positive relationship of household income to the number and quality of children, while the price effect refers to the phenomena wherein employed women incur higher

22

opportunity cost that women who do not work (Matysiak, 2011). In addition, results are in line with the initial findings of Lundberg & Rose (1999) who cited that this trade off between fertility and women’s employment status may also be due to the comparative advantage of each gender. Given that women have comparative advantage in the provision in commodity production (ie. home-making) and men have comparative advantage in earning as market inputs, then family utility will be maximized if specialization in household time allocation takes place. Furthermore, in accordance to the Time

Allocation Theory by Becker (1965), members of the household who are more efficient doing market activities (i.e. labor) would devote more time doing such activities, reducing time spent in home production; thus, more efficient market earners would then result to a reallocation of time spent between home and work.

On the other hand, the results of the regression show that the effect of fertility to the change of the probability of a woman being employed part-time shows a positive correlation. This is attributed to the short-run effect of increased contraceptive use resulting to the increase in labor supply, because women are now more readily available to participate in the labor market.

Fecundity a. Random (RANDM)

Fecundity, being the innate capacity of a woman to bear children, can change over time due to biological factors that affect their ability to produce children such as deterioration of health, and old age. The random component of fecundity accounts for this unprecedented change in fecundity levels, as it measures the exogenous variations outside the couple’s control. It is generally uncorrelated with past or historical births, and the couple’s fertility preferences. The results show that the random component of fecundity has a negative relationship with both full-time and part-time employment.

Since the measure is statistically significant, it means that couples’ fertility control measures are imperfect, and the decision of labor force participation is limited by women’s fertility outcomes. If their conception is indiscriminate or unplanned, employment decisions would also be indiscriminately affected. Thus, we can observe that women’s full-time employment is affected more negatively than part-time employment. Given the chance that they conceive, part-time work is not a significant option because it does not assure stability of tenure. Alternatively, full-time work gives women security in employment even with the risk of conception, thus the probability of being employed full-time is reduced by a higher amount compared to part-time work, when exogenous changes in fecundity levels are introduced.

23

b. Fixed (FIXED)

The fixed component of fecundity is that which does not change over time. Theoretically, this measure of reproductive viability remains persistent as the number of periods or years approach infinity. We can say that the fixed, or persistent measure of fecundity, is the benchmark for appropriate adjustments that couples use for their contraceptive efforts. The estimates show that this fixed component in itself is negatively related to women’s probability of employment. If the persistence of fecundity for the wife is high, there is an increase in the difficulty of family planning, since couples would need to adopt more effective contraceptive methods. This reduced ability to control for the number of children, and the length of time interval between births, would make the household decision for employment divergent to that of being a singular choice, since women are more susceptible to childbearing. This is true when couples do not make efforts for contraceptive use, or are using ineffective methods whose success rates are much lower. It can also be said that the heightened effort needed to discontinue conception negatively affects the decision for women to work or not. An explanation could be the increased cost attributed to contraception, rooting from the need to use more effective, or even permanent contraceptive techniques such as male or female sterilization. The more negative relationship of fecundity with full time employment can be explained as, without the use of contraception, there is no method of control with respect to the number of children a couple may produce, given that both are still in the childbearing age. The decreased level of control leads to the uncertainty as to how time-allocation will be made in the household, ultimately affecting their labor force participation decision.

Interaction Variables

We note that employment and women’s education have been viewed as having a positive relationship Cheng (1999) and Schultz (1997). The positive relationship does not hold however when such factors interact with fertility. The interaction variables between education and fertility, and education and fecundity, show an insignificant relationship to both full time and part time employment. Age and fertility exudes an insignificant relationship with women’s full-time and parttime employment in the presence of fecundity; but in the presence of fertility the relationship is significant. The indirect correlation between age, fertility and part-time employment is attributed to the preference of women to care for their children instead of working (opportunity cost), whereas the direct relationship between age, fertility and full time employment is due to the need to work for child cost financing. The interaction variable, wealth and fertility, exhibits a positive relationship with the dependent variable, as women must work to provide for the needs of her children. Noted here is the insignificance of all interaction variables with respect to part-time employment, this may be due to the

24

fact that part-time employment cannot capture the effects of such variables because the true effect of these demographic variables’ interaction with fertility and fecundity only comes out when related to full time employment.

Sectoral employment and fertility (AGRIR, MANUR, SERVR, AGRIF, MANUF, SERVF)

We disaggregate employed women into standardized occupation groups based on NDHS, where employment is defined for both self-employed and wage workers. The interaction variables for fertility and sectoral employment are significant and positively related to the probability of working part-time.

This means that all year round, there are employment opportunities available in the three main industry sectors namely the agricultural, manufacturing, and service sector. Looking at the results for full time work, there are some peculiarities we observed. For both the agricultural and manufacturing sector, skills learned are industry-exclusive, and most types of work are highly manual and labor intensive. Those who work in these sectors tend to develop highly specialized skills over time. Thus the prospect of inter-industry transfer of labor is not of relevant consideration. This is reflected in the positive relationship that exists for full time work and being employed in the agricultural and manufacturing sectors. When women have more children, they would need to find a sustainable source of employment and since skills obtained in the said sectors are specialized, women devote their time for employment fully in these sectors. On the other hand, we observe a negative relationship for the service sector. There are several key points to highlight in these observations First, we identify the decision between family size as a result of a higher conception rate and the quality of employment.

The effect of fertility on women’s employment is generally negative, whether part-time or full-time.

However, the same is not true for women working in the service sector. This can be associated with the degree of informality of job opportunities for women. Hausmann & Szekely (1999) and

UNESCAP qualifies informal employment as those outside the framework of labor regulations.

Accordingly, the reasons for non-coverage include the invalidity of the enterprise where the job is located, the non-protection of certain jobs by labour legislation such as subcontracting agreements and atypical jobs, and the existence of a vague employer-employee relationship (Haussman & Szekely,

1999). The service sector is diverse, and can be characterized with having some degree of informality.

The NDHS classification included household and domestic employment, clerical, professional and technical, and sales work. Out of those employed in the service sector, 30% were employed in domestic and household work including unclassified services, 37% employed in technical, professional, and managerial work, 28% in sales, and 5% in clerical work. Thus, we observe the shift in the quality of employment, here implied by the degree of job formality, with higher levels of fertility. This implies the tendency for women to forgo low-quality job opportunities for reasons of

25

childrearing. Women would only keep jobs that are worthwhile. Interestingly, Delpiano (2008) observed the negative impact of increasing family size to women’s employment. He found that women tend to leave low-quality jobs when faced with the responsibility of childrearing only if the family is small, and will only leave better-quality jobs at higher levels of increase in family size via the number of children.

When fecundity is used as a determinant of women’s employment status, we observe a convergence across all sectors for both full-time and part time work. Generally, more fecund women who are currently working are more inclined to participate in the labor force, despite the higher chances of having more children in the future. It is interesting to note that all sectors, whether full-time or part-time work, are positively related to sector and fecundity. The only difference lies in the numerical values of the marginal effects. Using fecundity as a benchmark, the probabilities are underestimated when fertility is used. Mathematically, the marginal effects estimates for the interaction variables are overestimated when fertility is used as an explanatory variable. This is consistent with estimation results of Kim & Aassve (2006).

5.3 Post-estimation Procedures

The Wald’s Test

With J dependent categories, there are J-1 non-redundant, coefficients associated with each independent variable x k .

The hypothesis that x k does not affect the dependent variable is written as:

Ho :

k ,1| Base

0

Wherein Base is the base category; since

|

is necessarily zero, the hypothesis imposes constraints on J-1 parameters.

The Wald’s Test is defined by Freese & Long (2000) is as follows, let β k be the J-1 coefficients associated with x k

, and

Var

k be the estimated covariance matrix. The Wald statistic for the hypothesis that all coefficients associated with x k

are simultaneously zero shown as:

W k

ˆ

k

'

Var

(

k

)

1

ˆ

k

. If the null hypothesis is true, then W k is distributed as chi-square with J-1 degrees of freedom.

The results from Stata showed the following results as seen in Tables 5.7 and 5.8.

26

EMPST

Weduc

Heduc

Woage

Huage

Wealt

Tyres

Fixed

Randm

Agrifec

Manufec

Servfec

AgeFec

EduFec

WelFec

Woage 2

Huage 2

Table 5.7

Wald’s Test on Women’s Employment Status (Fecundity)

Chi2

59.565

37.588

68.569

3.935

159.098

10.070

100.683

100.683

1493.009

591.090

2307.270

1.799

0.346

17.512

44.286

2.209

P>chi2

0.000

0.000

0.000

0.140

0.000

0.007

0.000

0.000

0.000

0.000

0.000

0.407

0.841

0.000

0.000

0.331

Table 5.8

Wald’s Test on Women’s Employment Status (Fertility)

EMPST

Weduc

Heduc

Woage

Huage

Wealt

Tyres

Ceptrhat

Agrif

Manuf

Servf

Ageft

Edfrt

Welft

Woage 2

Huage 2

Chi2

184.231

106.817

1.159

9.072

259.322

7.317

30.561

169.549

71.367

411.465

43.621

11.764

92.234

3.774

6.414

P>chi2

0.000

0.000

0.560

0.011

0.000

0.026

0.000

0.000

0.000

0.000

0.000

0.003

0.000

0.152

0.040

Tables 5.7 and 5.8 show the post-estimation results from the Wald’s Test. Basing from the p-value of each individual variables, the exogenous variables from the two models of women employment status are highly significant, with the exception of the partner’s age and partner’s age 2 , Edufec and Agefec for the fecundity model, whereas women’s age and women’s age 2 are deemed insignificant under the fecundity model. This shows that the demographic and interaction variables have a distinct correlation with the dependent variable, women’s employment status.

27

VI. CONCLUSION

Parenthood in the 21 st century has led to a convergence between household and work responsibilities between men and women, and as a consequence, there is now a need for reallocation of time between home and work. We focused on the distinction between fertility and fecundity, the former being the manifestation, measured using the number of births, of the latter, which is the inherent capacity of a woman to reproduce.

Our attempt to segregate the exogenous component of fertility, or that which is not influenced by couple’s preferences required us to adopt a method that incorporated both biological and demographic factors that affect birth production, herein referred to as the reproduction function. As mentioned, it was through this function we were able to arrive at appropriate measures for fecundity. The Tobit estimation of the reproduction function resulted to more valid estimates compared to the OLS estimation results, since majority of women in the survey had conception rates equal to zero over the time period considered. The fixed and random components of fecundity were isolated using the predicted values of the conception rate, and were used in the subsequent estimation of the employment status function. Furthermore, our data from the NDHS provided us with three categories for women’s type of employment, specifically all-year, seasonal, or occasional, used as categorical dummy variables for the multinomial logistic regression of our employment status function.

In general, the perception of women regarding employment opportunities in the Philippines links the negative relationship observed between fertility, fecundity and women’s employment status.

The 21st century has seen a convergence in the traditional family roles of men and women, as both genders now have identical employment opportunities that continue to shape their preferences. Today, the decision to participate in labor market activities rests on a cost-benefit analysis, where opportunity costs plays a huge role. From the findings, although fecundity is a more appropriate measure of the capability of women to reproduce, not many women have full knowledge of its impact to their employment decisions in the future, as fecundity is innate and biological in nature. The potential increased usage of contraception among fecund women may result to an increase in labor supply, here taken as the amount of time invested in the workplace; as a result, women are now more readily available to participate in the labor market. Furthermore, the probability of working full-time has been found to be closely linked to fecundity rather than fertility, as evidenced by the more negative effect of the fixed component of fecundity to full-time employment. It has been said that more fecund women tend to use more effective contraception techniques, in order to modify their fecundity horizon. With more effective contraception, there is an increased control of fecundity that limits the childbearing capacity of a woman leading to more available time for other activities aside from motherhood, such as full-time labor participation.

28

VII. Policy Recommendation

1.1 Domestic

The Responsible Parenthood and Reproductive Health Law of 2012 was declared as an expression of the universal human right to make a free and informed choice, whose guiding principle is to promote the rights and welfare of women, adults, couples, adolescents, and children. To reiterate, the group is not making a concrete stand on the recent passage of this Act.

With the passage of this act, it may imply a strengthened ability of couples to meet their desired number of offspring and length of birth intervals through the widened distribution of non-abortifacient contraceptive techniques and the increased promotion of traditional and natural pregnancy control methods, the choice of which is based on the preference of the couple.

In relation to our study, we recognize that the possible interim effect of the Reproductive

Health Law is the anticipated increase in women’s available time for work due to their increased ability to control the frequency and spacing of their conception. To explain this possibility, contraception enables women to alter their fecundity horizon, thus influencing their actual reproductive capacity. Women who have been previously employed part-time may engage in full-time employment opportunities, while those who have not been previously working due to their childrearing responsibility may now be able to participate in part-time employment opportunities. All of these recommendations however, rest upon the actualization of the goals set by the Reproductive

Health Law. This increased participation of women in the labor market prompts the need for the government to generate more employment opportunities.

These findings emphasize the possible consequences of controlling fecundity and its effect to fertility outcomes, and the significant relationship of these consequences to the local labor market. The goal of increasing labor market productivity must not only have an intermediate effect, but instead a sustainable one. Other factors that influence women’s employability must also be taken into consideration if the government wants to fully utilize the potential of the increased labor force participation. Investments in human capital development such as education and health are priorities that need equal attention, for these are tools that improve the quality of labor force.

Key to the economic progress of the Philippines is the realization of its demographic dividend, the accelerated economic growth rooted from fertility decline and the change of the country’s age structure. Our young population is a manifestation of a strong labor force, whose optimal potential lies in rousing the growth engines that would lead the country to advance. This growing population, along with the rising demand for labor domestically, has also highlighted the role of women in society, that which has been extended to include their contribution to productive economic activities corresponding to their equally important roles as mothers. This increase in availability of employment opportunities

29

has led to the crystallization of gender roles, and the household decision of labor force participation can now be considered as a decision carried out by both husband and wife. With this, family planning and the realization of the fecundity horizon of a couple plays an intensified role to the employment decision of a woman.

1.2 International

Although these results have significant implications for local policies, it may also add insight on international notions. The ASEAN prompts to pilot labor mobility for skilled workers by 2015.

This initiative will cause countries such as Thailand to experience long-term shortage of unskilled labor (Sabayjai, 2012).

The Republic Health Act will surely decrease the population in the long-term because these contraceptives can suppress fecundity and therefore, allow less entrants in the labor market after around 10 years. However, for women who are already taking contraceptives, they will most likely join the labor market; thus, causing an over-supply in the Philippines. Because most of the laborers in the country are categorized under unskilled, the over-spills of the labor market can be beneficial for countries with unskilled labor shortage.

For all countries in the region to see a solution in each other’s labor problems, labor mobility for both skilled and unskilled would be recommended. This proposition allows countries like Thailand to continue their progress as an economy—with many developments in need of unskilled labor. In addition, it allows the Philippines to pacify its problem of labor oversupply.

30

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

Alessandri, S. (1992). Effects of maternal work status in single-parent families: Children's perception of self and family and school achievement. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology , 54 , pp. 417-

433.

Anxo, D. et al. (2007). Time allocation between work and family over the lifecycle: A comparative gender analysis of Italy, France, Sweden and the United States . Retrieved from http://www.fep.up.pt/conferences/iwplms/documentos/WP_Papers/Paper_Anxo.pdf.

Apel, R. (2009). Instrumental variables estimation (with examples from criminology). Center for social and demographic analysis , 6-12.

Becker, G. (1965). A Theory of the Allocation of Time. The Economic Journal , Vol. 75, No. 299. (Sep.,

1965), pp. 493-517. Retrieved from http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0013

0133%28196509%2975%3A299%3C493%3AATOTAO%3E2.0.CO%3B2-N

Becker, G. (1985). “Human Capital, Efforts, and the Sexual Division of Labour”, Journal of

Labour Economics, 3(1), Part 2, January, pp. S33-58..

Cahuc, P. and Zylberberg, A. (2004). Labor Economics . MIT Press.

Chhachhi, A. "Concepts in Feminist Theory--- Consensus and Controversy". Gender in Caribbean

Development ed. Mahomed and Shepherd (UWI, Sept. 1986), p.8.

Chenery, H. B., Srinivasan, T. N., Behrman, J. R., Rodrik, D., & Rosenzweig, M. R.

(19882010). Handbook of development economics . Amsterdam: North-Holland ;.