Abstract

2004 European Applied Business Reshearch Conference Edinburgh Scotland

Creating The Knowledge Based

Organization Through Learning

Implementation Framework:

Conceptual Model Of Slovenian Enterprises

Vlado Dimovski, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia

Sandra Penger, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia

Abstract

As we enter the first decade in the twenty-first century, contemporary management thinking is being profoundly reshaped by two new convictions: managing organizational knowledge effectively is essential to achieving competitive success; and managing knowledge is now a central concern and must become a basic skill of a modern manager. In the paper we would like to present the impact of the increased interconnectivity of people and organization, and to perform the new organizational paradigm that provides a modern knowledge construction of the 21 st century organization. Therefore, the paper focuses on the process of attaining a knowledge organization, and enlightens different theoretical architectures of the 21st century organization.

Modern forms of organizational structures range from horizontal, process and team structures to virtual networks. The purpose of paper is to show signs of the Knowledge Based Organization in the Knowledge Based Economy, and to extent the creation of Learning Organization through

Learning Implementation Framework from Slovenian economy perspective. The Slovenian

Institute for Learning Enterprises today plays the leading role in the knowledge society, linking and distributing learning practices among Slovenian enterprises. On May 1, 2004, Slovenia has become a full member of the EU, and consequently, the role of Institute will become even more important in the implementation of learning organization culture in Slovenian economy.

1. Introduction

In the internet driven knowledge economy, more and more of the knowledge a firm needs to create economic value will be possessed by knowledge workers. An important challenge in managing knowledge to perform a learning organization is to create economic and organizational incentives for knowledge workers to keep their tacit knowledge within the firm .

In the Knowledge Based Economy, the production and distribution of information and knowledge is the main source of a company's assets.

Full understanding, organizational learning and knowledge management need to be developed, in order that an organization can learn more rapidly than its competitors. A major challenge in knowledge management is the transformation of personal and tacit knowledge into organizational knowledge. The increasing rate of environmental change and technological complexity demands organizational forms in which knowledge-based information is widely distributed. Consequently different views about the future organization are being formed in the organizational environment of the 21 st century. We illustrate the impact of organizational paradigm in Slovenian economy with a case study, where we examine the SILE. This paper is based on the general cognition process research method. This basic method is further expanded with the descriptive method, compilation method, comparative method and case study method. The basic research contribution of this paper is its comprehensive theoretical overview of the most modern theoretical findings in the field of organizational theory and management science. Consequently, the presented results of the case study of

1

2004 European Applied Business Reshearch Conference Edinburgh Scotland

SILE are crucial for understanding management and organization paradigm on the doorstep of the 21 st century.

Ensuring business success in today’s dynamic environment is increasingly difficult. Therefore it is senior management’s role to formulate appropriate corporate strategy that will reflect the requirements of the modern business environment.

1.1. Challenges of the Modern Organizational Environment

The challenges that organizations at the beginning of the 21st century are facing are completely different from the challenges in the 70s' and 80s' of the 20th century. Therefore organizational concepts and the theory of organization are still developing (Palmer, Hardy, 2000, pg. 211). The tackling of fast changes and a learning process are the most challenging problems that modern managers are facing. Many managers are still holding on to the hierarchical, bureaucratic approach for managing organizations, which was dominating during the past decades

(DuBrin, 2000, pg. 190-192). The challenges of today's environment – global competition, ethical issues, rapid advance in information and telecommunication technologies, increasing application of electronic operations, knowledge and information, as the most important organizational capital, increasing employee demands for creative work and opportunities for personal and professional development – require completely different response from organizations, as they were used to up until now (Coulter, 1998, pg. 348; see Figure 1 ). Patterns used in the past, do not satisfy the guidance needs of the 21 st century organization.

Figure 1: The Modern Organizational Environment

1.2. Towards the Knowledge Based Economy and Organization

The knowledge economy is gaining ground and establishing a new framework for modern organizational and management theory. The future of the management process raises the issues how to manage information and knowledge and how to develop intellectual capital. While managers of the industrial age focused on the control of business operations and on hierarchical structures, the new era managers, i.e. e-managers, will structure and build associations of self-managed virtual teams (Savage, 1996, Earl, Fenny, 2000). Organizations try to achieve their

2

2004 European Applied Business Reshearch Conference Edinburgh Scotland goals by building, leveraging, and maintaining competences (Sanchez, 2003, pg. 7). Competence building is the process of creating or acquiring new kinds of assets and capabilities use in taking actions. Competence leveraging is a coordination of the use of organization’s current assets and its capabilities in taking actions. Competence maintaining is the maintaining of an organization’s current assets and capabilities in the state of effectiveness for use in the actions which the organization is currently undertaking. The competitive position of economies, in particular of the highly industrialized countries, is already or will be determined by their capacity to create value through knowledge. In an economy where the only certainty is uncertainty, the one sure source of lasting competitive advantage is knowledge (Nonaka, Takeuchi, 1995, pg. 22). This structural change is reflected in theories of endogenous growth, which stress that development of know-how and technological change are the driving forces behind the lasting growth. Much of the literature on organizational learning and learning organizations (Argyris and

Schon, 1978; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995; Senge, 1990) highlights both, the transformation of personal knowledge into organizational knowledge and the transformation of tacit knowledge into explicit knowledge (Sanchez, 2003, pg. 46). The importance of knowledge management and organizational learning in competence based competition has been widely discussed in the recent literature (Argyris, 1986; Hamel and Heene, 1994; Hamel and Prahalad,

1994; Merali, 1997; Nonaka and Takeuchi, 1995; Sancez and Heene, 1997; Stonehouse et al., 1999; Miller, 1996).

Figure 2: Towards the Knowledge-Based Economy and Organization

3

2004 European Applied Business Reshearch Conference Edinburgh Scotland

Source: Dimovski, Penger, 2004, pg. 3.

As suggested in Figure 2, the importance of the knowledge based economy in related to the knowledge based organization, the knowledge based teams within the organization, and with the knowledge employees

(Dimovski, Penger, 2004, pg. 3). As the economy shifts to its dependence on knowledge, firm ownership will transfer to those individuals with knowledge resources. Just like the industrial revolution gave birth to the industrial model of a firm, so the knowledge revolution is replacing it with the new knowledge based model ( see Figure 2 ). A major challenge in knowledge management is the transformation of personal and tacit knowledge into organizational knowledge.

1.3. The Knowledge Management Views

Knowledge is fundamental to organizational competence, which Sancez, Heene, Thomas (1996, pg. 8) define as the ability to sustain the coordinated deployment of assets and capabilities in a way that promises to help a firm to achieve goals. We have different views on knowledge management ( see Figure 3 ). Knowledge, as a source of competitive advantage of an organization, is increasingly recognized as the principal source in the age of the knowledge-based economy. In the age of the knowledge economy, the process of management is undergoing radical

4

2004 European Applied Business Reshearch Conference Edinburgh Scotland changes in all dimensions of basic management functions. The traditional management process has built-in competitive advantages on the classic factors of production (land, labor, capital). In the knowledge era, the production and distribution of information and knowledge is the main source of a company's assets (Burton–Jones,

1999, pg. 42). Knowledge management is understood to be a process of systematic and proactive management and development of knowledge in the organization (Hansen, 1999, pg. 107). Unfortunately, there is no universal definition of knowledge management; in the broadest context knowledge management is the process through which organizations generate value from their intellectual and knowledge based assets (Santosus, Surmacz, 2003). Most often, generating values from such assets involves sharing them among employees, departments, and even with competitors in an effort to devise the best practices and competitive advantages. In order to understand how knowledge-based value creation works, management has to understand what knowledge is and how it is related to the competitiveness of a firm. In organizations, new knowledge is created continuously as employees learn and gain experiences. On the other hand, employees continuously seek information and knowledge in order to solve specific problems.

Figure 3: The Knowledge Management Definitions

Defining Knowledge Management

Evans (2003)

Sanchez (2003) The knowledge creation processes of firms require interaction between tacit and explicit forms of knowledge; KM it is a four phase process in which tacit knowledge is converted into explicit, and vice versa.

Van den Bosch, van Wijk (2003)

Argyris (1993)

Wiig (1998)

The process through which we translate the lessons learnt, residing in our individual brains, into information that everyone can use.

The knowledge creation process of a firm may be seen as social learning cycle in which knowledge cycles through three dimensions in the information space of firms: abstraction, diffusion, and codification of knowledge.

Knowledge is the capacity for effective action.

Knowledge can be thought of as the body of understandings, generalizations, and abstractions that we carry with us on a permanent or semi-permanent basis; we will consider knowledge to

5

2004 European Applied Business Reshearch Conference Edinburgh Scotland be the collection of mental units of all kinds that provides us with understandings and insights.

Malhotra (1998) KM caters to the critical issues of organizational adaptation, survival, and competence in the face of increasingly discontinuous environmental change; it embodies organizational processes that seek synergistic combination of data and information processing capacity of information technologies, and the creative capacity of human beings.

Wenig (1998) KM (for the organization): consist of activities focused on the organization gaining knowledge from its own experience and from the experience of others, and on the judicious application of that knowledge to fulfil the mission of the organization.

Murray (1998)

KM is a strategy that turns an organization’s intellectual assets into greater productivity, new value, and increased competitiveness.

Lynch (2000)

Kubr (2002)

Knowledge creation – the process of development and circulation of new knowledge –offers a dynamic strategic opportunity through three mechanisms: organizational learning, knowledge creation and acquisition, and knowledge transfer.

Knowledge management is understood to be a process of systematic, proactive management and the development of knowledge in the organization. Knowledge is the product of individual and collective learning , which is embodied in products, services, and systems.

Source: Algyris, Schon, 1978; Burton – Jones, 1999, pg. 35-45; Evans, 2003; Sanchez, 2003; van den Bosch, van Wijk, 2003; Lynch, 2000.

Understanding knowledge creation as a process of making tacit knowledge explicit has direct implications for how a company designs its organization and defines managerial roles and responsibilities within it. Knowledge is a product of individual and collective learning embodied in products, services and systems (Nonaka, Takeuchi,

1995, pg. 72). According to Nonaka and Takeuchi`s model, knowledge creation is a continuous and dynamic interaction between tacit and explicit knowledge which happens at the level of the individual, the group, the organization, and between organizations. Knowledge is therefore created through the interactions of knowledge in four different models (Nonaka, Takeuchi, 1995, pg. 72): (1) socialization, (2) externalization, (3) combination, and

(4) internalization.

As knowledge has to be seen as a valuable resource in organizations, attempts have been made to structure the knowledge base and attribute value to these assets. A widely publicized approach has been developed by the

Skandia Insurance Company in Sweden, which structures intellectual capital into (Tiwana, 2002, pg. 31): (1) human,

(2) organizational, and (3) customer capital. The intellectual index of Roos et al. (1998) is based on (1) relationship,

(2) innovation, (3) human, and (4) infrastructure capital (Kubr, 2002, pg. 422). For this reason a number of organizations have started to use the balanced scorecard model developed by Kaplan and Norton (2000. pg. 167) to integrate various assets of a company. The BSC model integrates four perspectives: (1) the financial perspective, (2) the customer perspective, (3) the process perspective, and (4) the learning and growth perspectives. The advantage of the model is that it allows different perspectives of an enterprise to be integrated and balances the financial, tangible aspects and intangible aspects of managing an enterprise. Intellectual capital is an intangible asset source which often isn’t stated on the balance sheet and in its broadest aspect includes human and structural capital (Lynch,

2000, pg. 298). Modern learning organizations build their lasting competitive advantages on knowledge and intellectual capital which also represents the only economic source of the modern organization (Kubr, 2002, pg.

422).

1.4. The Managerial Perspective of the Knowledge Based Organization

In order to ensure such modern operation of organizations, an exit from the so-called Smith, Taylor and

Fayol’s bottleneck has to be found. The future has to be built on a new, fifth generation of management, which is based on knowledge networking and emphasizes entrepreneurship and dynamic teamwork (see Figure 4 ).

Figure 4: The Knowledge Generation of Management: Towards the Knowledge Based Organization

6

2004 European Applied Business Reshearch Conference Edinburgh Scotland

Source: Adapted from Penger, 2001, pg. 24, Savage, 1996, pg. 120.

The fifth generation of management is based on five interconnected principles that define the Knowledge era ( see Figure 4 ; Savage, 1996, pg. 120): direct knowledge networking, continuous process improvement, comprehension of work as a dialogue, comprehension of time as a critical factor and virtual enterprising, which functions on the basis of dynamic team work. Learning organizations have to implement a horizontal method of work and form teams that concentrate on precisely specified tasks. Ohame (1995, pg. 270-284) explains that in today’s economy new technologies remove (past) informational inefficiency and therefore there is no need for highly hierarchical pyramids. As the economy shifts to dependence on knowledge, firm ownership will transfer to those individuals who own its knowledge resources. Just as industrial revolution gave birth to the industrial model of the firm, so the knowledge revolution is replacing it with new model (Burton – Jones, 1999, pg. 42, see Figure 6).

Goffe and Jones (2003, pg. 273) enlighten that networked organizations exhibit high levels of sociability but relatively low levels of solidarity. Business organizations with networked organizational cultures often benefit from informal social relations, in turn, facilitate flexible responses to problems, fast communications between members, and a preparedness to help. Networked cultures tend to emerge in organizations where: (1) knowledge of local markets is a critical cusses factor, (2) corporate success is an aggregate of local success, (3) there are few opportunities for transfer of learning between divisions or units, and (4) strategies are long –term.

2. Creating the Knowledge Based Organization

Many organizations are transforming into flexible, decentralized structures, which emphasize horizontal cooperation (Urlich, 1997, pg. 189). Besides that boundaries between organizations keep disappearing, as even competitors are forming partnerships with the intention to become globally competitive. A large part of the world economy is on-line. Organizations are networked in a constantly changing kaleidoscope of relationships (Shafritz,

Ott, 2001, pg. 528). New organizational forms enable organizations to respond to varied environmental pressures, including greater complexity, global presence, severe economic pressures, and incorporation of social values for more participative, learning oriented practices (Fulk, DeSanctis, 1999). Primary value of the organizational capital

7

2004 European Applied Business Reshearch Conference Edinburgh Scotland of modern organizations is not embedded in buildings but in information and knowledge (Burton–Jones, 1999, pg.

42).

Learning organizations build their sustainable competitive advantages on knowledge and intellectual capital which represents the only economic source of the modern organization. In the new environment numerous companies are following the learning organization’s concept while new networking virtual organizational structures prevail among these. Today’s managers will have to introduce completely new concepts in order to successfully manage a modern learning company. With the intention that modern organizations would more easily face environmental dynamics they must move toward a new paradigm, which is not based on mechanical assumptions of the industrial age but on the concept of a living biological system. Many organizations are transforming into flexible, decentralized structures, which emphasize horizontal cooperation. Besides that the boundaries between organizations are disappearing more and more, as even the competitors are forming partnerships with intentions to become globally competitive (Hasselbein, Goldsmith, Beckhard, 1997, pg. 112). New organizational forms have been labeled adhocracy (Mintzberg, 1983), technocracy (Burris, 1993), the internal market (Malone, 1980), knowledge linked organization (Badaracco, 1991), post-bureaucratic (Heckscher, 1994), virtual organization

(Davidow, Malone, 1992), and network (Powell, 1990) (adapted from Fulk, DeSanctis, 1999, pg. 501).

2.1. The Learning Organization Perspectives

Definitions and views of organizational learning and learning organization abound ( see Figure 5 ).

Organizational Learning and Learning Organization can be contrasted in terms of process versus structure

(Malhotra, 1996). Organizational learning involves systematic problem-solving, experimentation with new approaches, learning from experience and best practice, and transferring knowledge quickly and efficiently through the organization in ways that manifest themselves in measurable output (Garvin, 1993, pg. 78). Garvin (1993) defines a learning organization as one able to create, acquire and transfer knowledge, and to change its behavior to reflect new knowledge. A learning organization represents the highest level of horizontal coordination, where all traces of organizational hierarchy are removed (Dimovski, Penger, 2003, pg. 35-38). Such organization is based on equality, open information, empowered employees, low hierarchical levels and culture, which stimulates adaptability and cooperation and thus development of ideas wherever within an organization, so the latter is able to more rapidly discover opportunities and fight with crises. In a learning organization problem solving has the highest value, while traditional organizations follow efficient operations.

Figure 5: The Learning Organization Perspectives

Views of Organization Learning

Organizational learning as a knowledge acquisition (the development of skills, insights and relationships); knowledge sharing and dissemination: and knowledge utilization (the integration of learning to make it widely available to new situations).

Organizational learning as an adaptation of changes, and as a process of improving actions through

8

2004 European Applied Business Reshearch Conference Edinburgh Scotland

better knowledge and understanding.

Organizational learning as the enhanced ability to perform in accordance with a changing environment through the search for strategies to cope with those contingencies, and the development of appropriate systems and structures.

Defining Learning Organization

Argyris (1978) LO is a process of detection and correction of errors. Organizations learn through individuals acting as agents for them.

Huber (1991) LO is linked by four constructs: knowledge acquisition, information distribution, information interpretation, and organizational memory.

Huczynski,

Buchanan

(2001)

Senge (1990)

LO facilitates communication and cooperation by including everybody in problem identification and problem solving process, which enables the organization to continuously experiment with, improve and enlarge its capabilities.

LO are organizations where people continually expand their capacity to create the results they truly desire, where new and expansive patterns of thinking are nurtured, where collective aspiration is set free, and where people are continually learning to see the whole together. The five elements identified by Senge (1990) are said to be converging to innovate learning organizations. They are: (1) system thinking, (2) personal mastery,

(3) mental models, (4) building a shared vision, and (5) team learning.

Weick (1991) Organizational learning is a process within a learning organization by which knowledge is about action – the outcome relationship and the effect of the environment on these relationships is developed.

Malhotra (1996) LO learn from their experiences rather than being bound by their past experiences.

Management practices of LO encourage, recognize, and reward: openness, systemic thinking, creativity, a sense of efficacy, and empathy.

Daft,

(2001)

Marcic A learning organization requires specific changes in leadership, management and structure, the delegation of more powers to the employees, communications, participative strategy and adaptive culture.

Source: Adapted from: Algyris, Schon, 1978; Malhotra, Miller, 1996; 1996; Senge, 1990; Palmer, Hardy, 2000; Garvin, 1993; Nonaka, Takeuchi,

1995; Sanchez, 2003; Kubr, 2002; Evans, 2003.

2.2. The Learning Organization Evolution Process

The learning organization model is considered to be the top stage of horizontal coordination, with no traces of organizational hierarchy remaining (see Figure 6) . Complete understanding, organizational learning and knowledge management need to be developed in order that an organization learns more rapidly than its competitors

(Dimovski, 1994). Modern forms of organizational structures range from horizontal, process and team structures to virtual networks (Laubacher, Malone, 2000, pg. 215). New flattened organizational structures facilitate communication and cooperation. Thus everybody is involved in identification and problem solving, which enables an organization to continuously experiment, improve and increase its capabilities. Information technology interweaves organizational structure which is based on equality, open information, low level of hierarchy and culture

– the latter facilitating adaptability and cooperation. In a state-of-the-art horizontal organizational structure, the vertical structure shifts top managers away from the technical staff. An extended chain of command inspires the delegation process and consequently the empowerment of employees. Cross-functional teams are at the heart of current efforts to horizontally integrate the firm. Miles and Snow (1995) argue that such cross-functional teams should be self-managing, and the organization should heavily invest in skills for self-management of teams. Crossfunctional teams provide a more flexible alternative to horizontal coordination and offer the responsiveness needed for rapid action and better understanding of business processes.

Figure 6: The Learning Organization Evolution Process

9

2004 European Applied Business Reshearch Conference Edinburgh Scotland

Just as is knowledge fundamental to organizational competence, so is managerial knowledge fundamental to managerial competence (Sanchez, 2003, pg. 160-174). At he most basic level, several forms of managerial knowledge components are the building blocks of managerial knowledge domains relating to functional, technical, company, and environmental meters. These knowledge domains are the building blocks of the integrated managerial knowledge that each individual manager develops in performing his/her job. To manage knowledge and knowledge creation effectively within the organization managers need to understand not just the stocks of knowledge but also how to manage actual and potential transfers and diffusions. When integrated organizationally, individual managers′ capabilities collectively constitute a firm’s managerial capabilities. Intelligent organizations concentrate on the creation of the new knowledge that embodies a cornerstone of a lasting competitive advantage. The gaining of the competitive advantage results from the uniqueness of the network connections that the company establishes with its suppliers, distribution channels and end-customers (Etihaj, Guler, Sigh, 2000; see also Porter, 1985). Traditional value chains become fragmented – deconstructed into numerous business segments within which their own specific bases of competitive advantage will be formed.

2.3. The Learning Organization Implementation Framework

The learning organization implementation framework integrated with the organizational learning cycles is shown in figure 7 . Implementation framework of learning organization consists of four implementation paths through three phases: (1) From information management to knowledge management, (2) knowledge workers as change agents, (3) the problem oriented path, and (4) the top-down approach. At the left of figure 7 the organizational learning cycles are integrated into the conceptual model of implementation of a learning organization.

The five learning cycles represent the fundamental processes through which an organization receives, evaluates, absorbs or rejects, and deploys new knowledge (Sanchez, 2003. pg. 24). To create a learning organization, managers must support processes in each of the five learning cycles that will stimulate the challenging of current organizational knowledge by the individuals within the organization. All five cycles must function effectively for the overall learning dynamics to be sustained. A breakdown in any of the five cycles will cause a breakdown of learning and knowledge leveraging processes in the organization as a whole. In the knowledge economy knowledge

10

2004 European Applied Business Reshearch Conference Edinburgh Scotland workers which are capable of generating new knowledge and improved interpretative learning frameworks expect more than just financial incentives from the organizations they work for. Knowledge workers increasingly expect their employing organizations to provide them with superior opportunities to sustain their individual learning processes.

Figure 7: Learning Organization Implementation Framework Integrated with Learning Cycles

Source: Adopted from SILE (Slovenian Institute for Learning Enterprises (Framework); Kubr, 2002, pg. 425-431, Sanchez, 2003, pg. 4-15.

3. The Slovenian Institute for Learning Enterprises (SILE)

3.1. The Activities of Slovenian Institute for Learning Enterprises

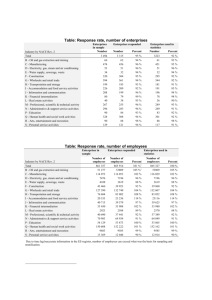

Slovenian Institute for Learning Enterprises (SILE) was registered as a non-profit institute in January 2001

(http://www.i-usp.si/eng/) ( see Figure 8 for detail data on SILE activities). It was established by 18 major flourishing Slovenian enterprises with the aim of developing the concept of learning organization (LO) and diffusing the concept of knowledge management (KM) to become a regular practice in Slovenian enterprises. In the course of its development, further 17 successful enterprises joined SILE, which today comprises no less than 35 most prosperous enterprises in Slovenia. Research is the main activity of SILE. Every year they carry out a research on learning organization among 500 Slovenian enterprises, based on S10 standards and 8C (criteria) conceptual model of learning organization attaining model of SILE ( as suggested in Figure 9 - 8C model to build up the learning organization of SILE).

Each year award winners of SILE present the operation and development of the learning society to other members of the Institute at their annual meetings. The Slovenian SILE today plays the leading role in the knowledge society, linking and distributing learning practices among Slovenian enterprises. SILE operational policies build on the process of permanent improvement of business efficiency through a continuous development of both individuals and teams, and through a continuous adjustment to new learnings from the environment.

In the year 2003, the research on the path to a learning organization has been running for the third year. The aim of the research was to assess the development level of the learning organization concept in Slovenian enterprises and to select the enterprises that, in 2002, have come closest to the concept of the learning society. The research covered 500 biggest Slovenian enterprises, 98 that is 19.6 per cent of which, responded to the research. As far as the

11

2004 European Applied Business Reshearch Conference Edinburgh Scotland presence of the elements of learning organization is concerned the research has revealed the trend of a growing awareness among Slovenian enterprises that in the economy of knowledge their employees are becoming an increasingly important factor of competitive advantage. Slovenian enterprises still have plenty of reserves available in the implementation of the LO concept. The largest reserves have been found in the development of management for individual roles in the economy of knowledge, as well as in systematic formation of the knowledge management process, and the use of effective tools for measuring the impact of investments in knowledge. The most important finding of the research is the positive correlation between the implementation of the learning organization concept and the business effectiveness of Slovenian enterprises. The 2003 presentation of awards (for the year 2002) concluded with an international event, a symposium of 93 representatives of Slovenian economy visited by the management guru Arie de Geus.

The principal activity of SILE is a holistic research of the application of the learning organization concept in Slovenia. The research results in the award of a commendation for an excellent enterprise on the path to learning organization. Award winners are selected on the basis of a questionnaire according to the Rules for Research

Evaluation. In 2003, SILE presented awards to 10 best enterprises selected by SILE evaluation committee and the

Chamber of Commerce and Industry of Slovenia. The enterprises that have achieved the highest development level of learning organization are presented the award at the annual international symposium. In 2004, management guru

Peter Senge has visited Slovenia on that occasion (May 18, 2004).

Figure 8: Slovenian Institute for Learning Enterprises (SILE)

12

2004 European Applied Business Reshearch Conference Edinburgh Scotland

Slovenian Institute for Learning Enterprises (SILE)

MISSION

STATEMENT

DEFINITION

LEARNING

ORGANIZATION

(SILE)

OF

The promotion of the knowledge development in enterprises in order to maximize their business efficiency.

LO is based on a planned implementation of change-oriented organizational culture, the development of systematic knowledge management, the designing of efficient innovation systems, as well as on quality and partnership relations, all of which enable enterprises to achieve their strategic goals efficiently and effectively.

DIRECTIVES FOR

LEARNING

ORGANIZATION

(SILE)

Learning organizations differ from traditional enterprises in: (1) systematic resolution of problems; (2) systematic searching to acquire and practically test new learnings; (3) learning lessons from previous results and failures; (4) benchmarking; and (5) in fast and efficient transfer of knowledge within the enterprise.

TRANSFORMATIO

N INTO LEARNING

ORGANIZATION

AWARD WINNERS

(companies)

ACTIVITIES

SILE

OF

Transformation is a long-running process that starts at the strategic level with clear definition of the learning organization concept in the vision, goals and strategy of the enterprise. This then results in the change of the organizational culture, processes and structure.

(1) 2000 (3): Henkel Slovenija, Luka Koper., Zavarovalnica Triglav MS.

(2) 2001 (3) : Gorenje, Lek, Revoz.

(3) 2002 (10) : Arcont, Danfoss Trata, Gorenje, Iskra Mehanizmi, Lek, Johnson

Controls NTU, NLB, Mercator, Revoz and Trimo.

(1) Research in the theory and practice of the learning organization in Slovenia and abroad;

(2) Cooperation and networking with similar organizations in the country and worldwide (ECLO – European Consortium for the Learning Organization, www.eclo.org);

(3) Measurement of the learning society concept in enterprises – annual research projects.

BODIES OF SILE:

NETWORKING OF

LEARNING

ENTERPRISES IN

SLOVENIA

(1) Council of the Institute: consisting of members and founders;

(2) Scientific and program council: domestic and foreign experts.

(1) Meetings of experts in the field of learning;

(2) Development and technology workshops to raise the competitiveness of

Slovenian economy;

(3) Promotion of SILE members among Slovenian public (annual presentation of awards to the best).

3.2. The Cconceptual Model of the Slovenian Institute for Learning Enterprises

The conceptual model of the Slovenian Institute for Learning Enterprises builds on 11 principles (SILE,

2003): (1) Common vision and employees involvement in learning. (2) Systemic thought about the meaning of an enterprise as an open system connected with its environment and interdependence of subsystems within the enterprise. (3) Continuous and organized acquisition of new learnings and knowledge management. (4) Group learning and team principle. (5) Personal mastery and the role of individuals in their own development. (6) The role of a learning manager. (7) Partnership relations (8) Innovativeness and internal entrepreneurship. (9) Culture of changes. (10) Adjusted system of remuneration. (11) Quality of business process reengineering towards the learning organization framework. For the successful implementation of principles of a learning organization reengineering the organizational structures, processes, culture and systems must be reorganized. Organizational learning requires individual, group, and organizational processes that work together as a system, and the challenge for the managers

13

2004 European Applied Business Reshearch Conference Edinburgh Scotland of learning organizations is to design, support and continuously improve processes that make learning a systematic activity. Development standards for learning organizations (S10) are based on the evaluation model building on 10 elements. These standards aim at the achievement of higher efficiency in the implementation of the LO concept and provide a management tool. The model of standards is well proven, and training programs for internal and external appraisers of the LO concept are being prepared. The following are standard requirements: strategic aspect, management role, organizational culture, knowledge management, learning organization, the role of individuals, motivation system, business process reengineering, measurement of results, and effects of learning organization implementation process. In 2003, SILE set up an integrated model of knowledge management; it is aimed at the increasing of efficiency of investments in knowledge in Slovenian enterprises. The KM model is now being tested by a SILE member. Key projects and operation activities of SILE are: (1) Knowledge management project implementation: evaluation of knowledge vision in enterprises, assessment of knowledge and competences of enterprises, transfer of knowledge between employees; (2) Implementation of Slovenian standards of learning organization S10 /(10 standards of learning)/; (3) Project 8C - long-term implementation of the concept of learning organization ( see Figure 9 ); (4) Implementation of MBO (Managing by objectives) managerial tool in the business process of enterprises; and (5) Measurement of organizational culture.

Figure 9: Conceptual Model of the Slovenian Institute for Learning Enterprises

14

2004 European Applied Business Reshearch Conference Edinburgh Scotland

4. Conclusion

The aim of this paper is to study the essential literature on learning organization and knowledge management, and to enlarge the learning organization implementation framework for further theoretical and empirical testing among Slovenian learning enterprises. The objective is to exhibit the process of attaining the knowledge organizational paradigm in the Slovenian economic society. Consequently different views about the knowledge based organization are being formed. The Slovenian Institute for Learning Organization today plays the leading role in the knowledge society, linking and distributing learning practices among Slovenian enterprises.

Every year they carry out a research on learning organization among 500 Slovenian enterprises, based on conceptual model of learning organization attaining model. Operational policies are built on the process of permanent improvement of business efficiency through continuing development of both individuals and teams, and by continuous adjustment to new learnings from the environment. The principal activity of Institute is the holistic research in the application of learning organization concept in Slovenia. The research results in the award of commendation for excellent enterprise on the path to learning organization.

15

2004 European Applied Business Reshearch Conference Edinburgh Scotland

In the year 2004, SILE will continue to develop learning policy among Slovenian enterprises, and to build the society of knowledge in line with EU Directives. Based on the adopted Strategy for the Economic Development of Slovenia until 2006, and particularly on its guidelines regarding the building of a knowledge-based society, SILE will pursue its mission and act as an institutional promoter of the implementation of the elements of learning society.

As a member of the European Learning Society Association, SILE will build on innovation development, entrepreneurship and integration of knowledge of various actors, and contribute to the intensive development of

Slovenian economy. On May 1, 2004, Slovenia has become a full member of the EU and, consequently, the role of

SILE will become even more important in the implementation of learning organization culture in Slovenian enterprises. Due to the fact that Slovenia is a typically small and open economy, the concept of a learning society has become well established among Slovenian enterprises, thus creating a society of knowledge that, on May 1,

Slovenia has entered into the larger European society of knowledge.

References

1.

2.

Argyris C., Schon D. A. (1978): Organizational Learning. Reading: Addison Wesley.

Burton Jones Alan (1999): Knowledge Capitalism: Business, Work, and Learning in the New Economy.

Oxford: Oxford University Press, pg. 248.

3.

4.

5.

Cogner Jay A. (1997): How Generation Shifts Will Transform Organizational Life. The Organization of the

Future: Hesselbein Frances, Goldsmith Marshall, Beckhard Richard ed.: Jossey Basss Publishers, San

Francisco, pg. 394

Coulter Mary K. (2000): Strategic Management in Action. New Jersey: Prentice–Hall Inc., 1998.

6.

Daft Richard L., Marcic Dorothy (2001): Understanding Management. 3rd ed. Fort Worth: Harcourt

College Publishers.

Dimovski Vlado (1994): Organizational Learning and Competitive Advantage: A Theoretical and

Empirical Analysis.

Doctoral Disertation. Cleveland University.

7.

8.

Dimovski Vlado, Penger Sandra (2003): Virtual Management: A Cross Section of the Management Process

Illustrating Its Fundamental Functions of Planning, Organizing, Leading And Controlling in a New Era

Organization. Littleton: Journal of Business & Economic Research, Vol 1, No 10, pg. 27-36.

Dimovski Vlado, Penger Sandra: The Importance of Concept of Learning Organization in Slovenia.

Symposium – Peter Senge in Slovenia, 18 th of May 2004. Ljubljana: The Slovenian Institute for Learning

9.

Organization and Faculty of Economics Ljubljana May 2004 ( In Slovenian Language ).

DuBrin Andrew J. (2000): The Active Manager: How to Plan, Organize, Lead and Control Your Way to

Success. London: Thomson Learning.

10.

11.

Earl Michael, Feeny David (2000): How to Be a CEO for the Information Age. Sloan Management Review,

Boston, Vol 41, No 2, pg. 11-24.

Ethiraj Sendil, Guler Sisin, Singh Harbir (2000): The Impact of Internet and Electronic Technologies on

Firms and its Implications for Competitive Advantage. Working Paper. Philadelphia: The Wharton School.

12.

13.

Evans Christina (2003) (ed): Managing for Knowledge: The HRs Strategic Role Perspective. Oxford:

Butteworth Heinemann, pg. 276.

Fulk J., DeSanctis G (1999): Articulation of Communication Technology and Organizational Form. In

Shafritz Jay M., Ott Steven J (eds): Classics of Organization Theory. 5thed. NY: Harcourt Publishers, pg.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

542.

Garvin D. A. (1993): Building a Learning Organization. Harvard Business Review, July-August, pg. 78-79.

Hansen M. T. (1999): What is Your Strategy for Managing Knowledge, Harward Business Review, Mar. –

Apr., pg. 106-116.

Hesselbein Frances, Goldsmith Marshall, Beckhard Richard (1997): The Organizations of the Future. San

Francisco: Jossey Bass Publishers.

Huczynski Andrzej, Buchanan David: Organizational Behavior: An Introductory Text. 4th ed. New York:

Prentice Hall, 2001. 916 str.

Kaplan Robert S., Norton David P. (2000); Having Trouble with Your Strategy: Then Map It. Harvard

Business Review, Boston, Vol 78, No 9-10, pg. 167-175.

Kubr Milan (2002) (ed): Management Consulting, A Guide to the Profession, 4 th ed. International Labor

Organization, Geneva, pg. 903.

16

2004 European Applied Business Reshearch Conference Edinburgh Scotland

20.

Laubacher Robert J., Malone Thomas W. (2000): Retreat of the Firm and the Rise of Guilds: The

21.

22.

Employment Relationship in an Age of Virtual Business. 21st Century Initiative, Working Paper No 033.

Cambridge: MIT Sloan School of Management.

Lynch Richard (2000): Corporate Strategy. 2nd ed. Harlow: Financial Times Prentice Hall, pg. 1014.

Malhotra Yogesh (1996): Organizational Learning and Learning Organization: An Overview

(www.brint.com/papers/orglrng.html), January 2004.

23.

24.

Miles R., Snow C (1995): The New Networked Firm: A Spherical Structure Built on a Human Investment

Philosophy. Organizational Dynamics, Vol 23, No 4. pg. 5-18.

Miller D. (1996): A Preliminary Typology of Organizational Learning: Synthesizing the Literature, Journal

25.

of Management, Vol 22, No 3, pg. 485-505.

Nonaka Ikujiro, Takeuchi H. (1995): The Knowledge Creating Company. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pf. 72.

26.

27.

28.

Ohame Kenichi (1995): The Evolving Global Economy: Making Sense of the New World Order. Boston:

The Harvard Business Review Book, pg. 300.

Palmer Ian, Cynthia Hardy (2000): Thinking About Management. London: Sage Publications.

Porter Michael E. (1985): Competitive Advantage: Creating and Sustaining Superior Performance. New

29.

30.

York: Free Press.

Sancez R. Heene A., Thomas H. (1996): A Competence Perspective on Strategic Learning and Knowledge

Management. Wiley, Chicheter, pg. 234.

Sancez Ron, Heene Aime (1996): A Competence Perspective on Strategic Learning and Knowledge

31.

32.

Management. Wiley, Chicheter, pg. 234.

Sanchez R., Henne A. (1997) (eds): Strategic Learning and Knowledge Management. Chichester: John

Wiley.

Santosus Megan, Surmacz Jon (2003): The ABCs of Knowledge Management. Knowledge Management

33.

34.

Research Center.

Savage Charles M. (1996): Fifth Generation Management: Co-creating Through Virtual Enterprising,

Dynamic Teaming, and Knowledge Networking. Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann.

Senge P. M. (1990): The Fifth Discipline. The Art and Practice of the Learning Organization. London:

35.

36.

Random House, pg.424.

Slovenian Institute for Learning Enterprises (2003-2004): Internal Papers and Frameworks. (http://www.iusp.si/eng/).

Stonehouse George et al. (2000): Global and Transnational Business: Strategy and Management.

37.

38.

Chichester: Wiley.

Tiwana Amirt (2002): The Knowledge Management Toolkit, Orchestrating IT, Strategy, and Knowledge

Platforms, 2 nd ed, Prentice Hall, New York, pg. 383.

Urlich Dave (1997): Organizing Around Capabilities. The Organization of the Future: Hesselbein Frances,

39.

Goldsmith Marshall, Beckhard Richard ed.: Jossey Basss Publishers, San Francisco, pg. 394.

Van den Bosch Frans A. J., Van den Wijk Raymond (2003): Creation of Managerial Capabilities through

Managerial Knowledge Integration: A Competence Based Perspective. In Sanchez Ron (ed). Oxford:

Oxford University Press, pg. 159-176.

17