African American vernacular dance as a model for

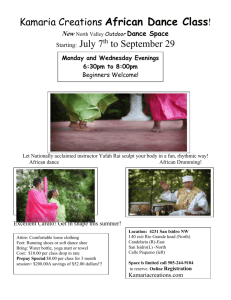

advertisement