Social measures. In contrast to the communication measures, the

advertisement

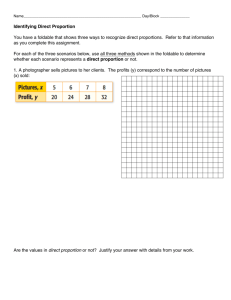

Social Contact and Communicative Competence in the Oldest Old1 Deborah Keller-Cohen, Amanda Toler, Diane Miller, Katherine Fiori, and Deborah Bybee University of Michigan Paper to be presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Psychological Association, Honolulu, July 28, 2004 1 We appreciate the comments of Evan Cohen and Kristine Ajrouch on earlier versions of this paper. 1 Introduction Despite the fact that the oldest old are the fastest growing segment of the population, the relationships among language, cognition and social engagement have not been examined in this age group. Indeed even the existing literature on oral language and aging has largely focused on adults under the age of 85. Change in the language of the elderly is typically attributed to neuro-cognitive decline (Au et al, 1995; Kemper et al,2001). Memory, attention, inhibition and processing speed have all been thought to play a role in how language changes with age. However these changes have varied across areas of linguistic knowledge. For example, vocabulary knowledge has been found to improve whereas word retrieval is compromised with aging (Au, 1995); (S. S. Kemper, A., 2001); (Borod, 1980). A decline in sentence complexity has been reported in statements of elderly adults but the same statements were judged to be more interesting than those by younger speakers(S. Kemper, Kynette, D., Rash, S., O'Brien, K., Sprott, R., 1989). Cognitive effects on communicative skills have not been uniform, i.e. there is no single dynamic that captures the relation of cognition to communication. What role social contact plays in the maintenance of communicative skills remains largely unexplored. It seems likely that social contact would impact the maintenance of language skills since evidence exists that social engagement is protective against cognitive decline (Seeman et al, 2001; Zunzunegui et al. (2003). The present investigation, a pilot study, focuses on social contact as well as some aspects of social networks and their relation to language and cognition in the oldest old. We use social contact here to refer to the engagement individuals have in their social world. This includes the frequency with which individuals interact with others, the range 2 of conversational partners and the variety of activities in which they engage. Social networks entail several features: objective (structural factors such as network size and composition) , functional (what the supportive others in the network actually do for the individual) , and subjective ( the individual’s qualitative evaluation of the relationships in the network) (Antonucci, 1990). Beckman et al. (2000:849) capture the connection between social contact and social networks observing that “through opportunities for engagement, social networks define and reinforce meaningful social roles.” How might social relationships relate to the maintenance of communicative skills? One hypothesis is that communicative competence is maintained by use. Individuals with a limited social engagement will over time begin to lose their ability to recruit the linguistic resources needed to maintain this competence (Ryan, 1995). An alternate hypothesis is that limited or unsatisfactory social contact has selective effects. Perhaps dimensions of language use that require a speaker to take another’s perspective into account are affected more by reduced social contact. These communicative skills might include providing instructions as well as descriptions sufficient to distinguish one referent from another. Our project examines the relationships among social engagement, cognition and communicative skills where social engagement is operationalized as the frequency, purpose and quality of interactions. Our hypothesis was that the frequency, purpose and satisfaction with social engagement would be related to higher performance on communicative tasks. We also expected that performance on our cognitive measure would be positively associated with higher levels of social contact and better language scores. Design 3 Participants The participants for our study were 20 non-Hispanic whites drawn from two retirement communities2 which were administratively part of a Protestant denomination retirement entity. Setting one, described as without programming, offered apartments in a building designated as senior residences. Although there was an occasional facility organized event such as the monthly birthday party, no roster of daily activities was planned. The second setting, referred to here as with programming, was an old established setting offering a continuum of services, from free standing independent apartments to dementia care. This setting offered a daily schedule of residential community events. All of our participants were living alone and independently in their own apartments; they were not in assisted living. We chose respondents in senior residences rather than community dwelling residents to ensure that individuals had the opportunity for regular social interaction due to their physical proximity to each other. It also allowed us to examine the effect of type of setting on communicative behavior. Because there were only five men in our sample, we were not able to include analyses based on gender although we plan to do so in the future. Procedures To obtain information about social contact, we modified the Rochester Interaction Record (Reis, 1991), a daily diary event-based recording instrument (See Figure 1). Nezlek, et al (2002) have used this instrument successfully with older adults. We limited 2 N= 7 from unprogrammed setting; N=13 from programmed setting. 4 its use to social situations involving talk3 that took place for five minutes or more since we were interested in the relationship between sustained social interaction and communicative skills. Participants were provided with notebooks organized into the days of the week, allowing us to collect objective, functional and subjective aspects of their social networks. All individuals were screened for dementia using the Cognistat (formerly known as the Neurobehavioral Cognitive Status Examination). It provides more information than the Mini-Mental State Exam, briefly measuring seven different cognitive functions: confrontation naming, simple auditory attention, recent verbal memory, verbal judgment, verbal abstract reasoning, mental calculations, and constructional skill. Following Drane et. al (2003) we used the composite score with the 9th percentile as a cut off for participation.4 Because of the breadth of information the Cognistat elicits, we also used it as our cognitive measure. Three language tasks were selected to reflect different aspects of communicative competence. The Boston Naming Test (BNT) taps into the ability to name referents and the ability to retrieve those names. (We used the full 60-item version). The tasks referred to here as WIAT Discourse are the Rollercoaster and Vending Machine items from the WIAT 2. In the Vending Machine task, the participant is asked to explain how to purchase candy from a vending machine to someone who does not know how to do this. They do this while looking at a set of pictures so that recall is not at issue . In the 3 The RIR in its original form does not require talk, but others have adapted it for talk. It also required interactions of 10 minutes or more which we felt was not appropriate for a much older population. 4 The composite score abandons the screen and metric approach of the Cognistat and instead uses the total score achieved on the test items (82). 5 Rollercoaster item, the individual is asked to create a story using a panel of five pictures showing three boys at an amusement park who have differing reactions to a rollercoaster ride. Here too the pictures are held in sight for the participant to consult. With a Cronbach’s alpha of .763, we combined those two tasks into one variable. Finally, the Cognistat Picture Description involves the ability to perceive the substance of a complex picture and convey that. Methods Our first step was to examine the bivariate relations among the communication measures, their relation to cognition and education, and the relations among the social measures using Pearson correlations. Because education was highly correlated with the BNT, we ran partial correlations using education as the control variable (see Table 5). To further explore the relationships among the linguistic and social variables, we selected those social variables that were significantly correlated with the language measures for inclusion in regressions. Because of the small sample size, we were limited in the number of variables we could include at once. Therefore, for each dependent variable we ran multiple models using a control variable and one social variable. We then evaluated the contribution of each of the social variables individually. In the case of the BNT, education served as the control variable in each of the models. However, the Composite Cognistat, rather than education was significantly correlated with the WIAT and remained significant after controlling for education. Therefore, we used the Cognistat as the control variable for the regressions with the WIAT as the dependent variable. The Picture Description was not correlated with either education or the Cognistat and did not 6 contribute significantly to subsequent regression models. Therefore, we dropped these controls and were able to include the social variables of interest simultaneously. Results Table 1 summarizes the performance of our participants on the social and language tasks. As a group participants with more than a high school education received higher scores on the language tasks, participated in a larger number of social interactions and participated with a greater diversity of individuals. Bivariate correlations Communication measures. We anticipated that performance among the language tasks would not be related because they tap different types of language skills: word retrieval, providing instructions, telling a story and describing a picture. As shown in Table 2, this is the case. Both the BNT and the WIAT discourse tasks were related to the Cognistat. Consistent with prior research, BNT scores were strongly associated with education although the WIAT Discourse scores were not. The picture description total word score was not related to any of the tasks and was dropped from subsequent analyses. The substance score was not associated with either education or the Cognistat. Social measures. In contrast to the communication measures, the social measures displayed many associations. This can be seen in Table 3. In part this was because some of the measures recorded overlapping behaviors. For example, each conversation log recorded at least one activity, although they could record more than one per log, so the number of logs and the number of activities were expected to be correlated. In other cases, the variables measure different behaviors such as the number of activities and type 7 of relationship. Their strong correlation may be due to a third factor such as the participant’s cognitive status. Importantly we found that the proportion of all interactions devoted to family members was negatively associated with three other social variables: the proportion of interactions with friends, the number of different types of relationships, and the number of different activities. That is, individuals whose interactions were more oriented toward family were involved with fewer friends, had a more limited variety of role relationships, and participated in fewer activities. All the social variables except the number of different activities were positively associated with performance on the Cognistat (see Table 4). Because setting might be a proxy for any number of contrasts, we examined it more closely. We found no association between setting and the number of different activities in which people participated despite the differences in programming. However we did observe a correlation between setting and number of different relationships. Those in the programmed setting were engaged in a wider variety of relationships than those in the unprogrammed setting. Moreover setting was associated with conversational partner. In particular, we found that setting was negatively correlated with the proportion of interactions with family members (see Table 4). In the unprogrammed setting, residents tended to interact more often with family members whereas in the setting with programming, residents interacted less often with family and with a wider variety of individuals overall. In fact, there was very little overlap in the frequency of interaction with family members between the two settings. Over half of the residents in the programmed setting interacted with one to four family members during the week, whereas nearly half of the 8 residents from the unprogammed setting interacted with nine to thirteen family members during the week (see Figure 2). Relationships among language, cognitive and social variables. Next we examined the relations among social, cognitive and communicative variables simultaneously. As we can see in Table 4, initial correlations of all the measures showed a number of social variables to be of interest: number of conversation logs completed, the residential setting, the number of activities, the number of different types of relationships represented across a week’s logs, the proportion of interactions involving family and the proportion of interactions involving friends. We did not observe an association between satisfaction and cognitive or communicative functions so that variable was dropped from subsequent analyses. Regression Results BNT. Performance on the BNT was predicted by models including education plus each of the following: setting, the number of different relationships, and the proportion of interactions involving family (see Table 6). Models 2, 3 and 5 were the most informative. Models 2 and 3 reveal that participants who had a wider range of relationships and a lower proportion of interactions with family members performed better on the BNT. Moreover, recall that the programmed setting had participants with a lower proportion of interactions with family. The association between the BNT and setting meant that the higher the score on the BNT the more likely they were to come from the second setting, i.e. the programmed setting WIAT Discourse. Table 7 summarizes the models for the WIAT discourse tasks. Model 5 was the most informative. Performance on the Cognistat plus residence in a particular 9 setting accounted for 42% of the variance, significant at the trend level (p=.086). Those with higher Cognistat scores living in the programmed setting performed better on the WIAT Discourse tasks Cognistat Picture Description. For the Picture Description (see Table 8) the model relating performance to number of different activities was significant; the model with logs was not. Both of these variables capture engagement in number and variety of activities. This differentiates the picture description from the other communication tasks. Discussion Much is known about the association between declines in cognitive function and the ability to communicate but little has been explored about what role social engagement might play in their relationship. This pilot study suggests that a consideration of social contact in the relationship between language and cognition in the oldest old is a fruitful avenue for further inquiry. The relationships among cognition, social contact and communication. One of the repeated observations here was that higher levels of performance on some language measures were associated with higher levels of cognitive functioning and a wider range of social contacts which confirms our hypothesis. An even more intriguing and unexpected finding was the inverse relationship between range of contacts and the proportion of contacts allocated to family. We also found that as the proportion of family contact increased, both the naming and discourse performances decreased. The proportion of family contact was also strongly related to Setting, i.e. programmed vs. unprogrammed. This Setting variable emerged as a clearer predictor than family contact. A fuller understanding of the family contact, setting and linguistic skill relationship 10 would require more settings and repeated measures over time. However, the current data suggest at least two possible explanations: a) functional decline; and b) normative patterns of family interaction. One possibility is that as individuals decline cognitively, they become less able to handle social contact and become more dependent on family members who by virtue of kin obligations, will continue to interact with them. The fact that we found a negative correlation between the number of logs (that is total number of interactions over five minutes), a measure of social activity, and the proportion of interactions with family does suggest the family may be filling a gap with those experiencing some cognitive decline. If that were the explanation, then cognitive decline might stimulate the pattern of social contact with family but it would still remain uncertain what the relationship was between social engagement and communicative competence. It could be that routinized exchanges between family members and the oldest old provide less stimulation for the maintenance of communicative skills. A detailed analysis of interactions with family is needed. A second explanation is that normative patterns of family interaction contribute to this pattern. Recall that we found the two settings differed in the proportion of interactions residents had with family members. It is possible that family members feel greater responsibility for their oldest-old relatives when the setting does not provide them with more opportunities for social engagement. The level of family participation might be subject to moderation if the oldest-old member reported changing involvement with non-family members. Longitudinal evidence would be required to assess that. Even so, it is also plausible that family members direct their loved ones to settings that are consistent with their attitudes toward interactional patterns. In this 11 account, socioeconomic status (SES) or cultural patterns of interaction might well guide their collective selection of a setting. The setting we have described as unprogrammed was considerably less expensive than the programmed setting which might point to SES as a factor in the selection of a residential setting for one’s parents. Another possibility is that SES and cognitive status interact here. Prior work has shown the protective benefits of education against dementia. With proportionately more residents with only a high school education in the unprogrammed setting and lower performance on the Cognistat, these factors may jointly work against the support of a high level of communicative competence. However, in the absence of cognitive decline, how might social engagement support communicative skills? (Crohan, 1989) argues that because friendship relations are voluntary, they may contribute more to the well being of the elderly than family relations. Individuals who are experiencing little cognitive decline involve themselves in a wider range of relationships, each of which challenges individuals to speak and listen to others on a range of topics and in a range of contexts all of which may contribute to keeping one’s linguistic skills activated. Communication measures. The current study also demonstrated that confrontation naming and discourse are two meaningful and separate communicative skills, and as such, should be included in any larger study. We found performance on the BNT to be highly correlated with education (consistent with a large body of prior research), whereas performance on the WIAT was not. It’s possible that vocabulary skills are enhanced by post-secondary education whereas the particular oral discourse skills we examined are not. 12 The absence of association among the language measures suggests that they represent different aspects of communicative competence, that is the ability to label aspects of the world and the ability to create different types of connected discourse. A larger sample will be needed to assess whether features of social engagement impact these domains of communicative behavior differently. Satisfaction, social contact and communication. The relationship between satisfaction with interactions and well being has been previously reported. Why would satisfaction not have been found related to our study variables? Carstensen(1997) and Fingerman(2003) report an increase in satisfaction with social relations with age; others report a decline in negative social exchanges or a low frequency of negative exchanges with age (Rook, 2003). This is consistent with the the absence of variation in satisfaction reported in the conversation logs. Participants were quite satisfied with their interactions. The oldest old in our sample seem to have restricted interactions to those they enjoy. Our study suggests that the time spent in contact with family members as conversational partners rather than a wider range of social contacts, was associated with lower communicative and cognitive performance. Our future work will involve a closer look at the patterns of family interactions and their relationship to functional decline and the maintenance of communication skills. This will require a multi-site, longitudinal effort. We will also be expanding the range of communicative skills so that we can more fully the assess the relationship of each skill to types of social contact. 13 Table 1 Descriptives of study variables Variable Range Full sample (n=20) Mean SD HS only (n=9) Mean SD More than HS (n=11) Mean SD Boston Naming Test (BNT) 43-59 50.50 4.926 46.22 2.59 54 3.29 WIAT Discourse5 7-24 17.3 4.60 16.00 5.10 18.36 4.08 Picture Description6 0-1 .5973 Composite Cognistat 64-80 72.95 5.206 69.44 5.25 75.82 3.06 # of social logs 9-58 25.7 11.40 19.78 7.68 30.55 11.93 # of diff. Types relationships 1-6 4.35 1.23 3.67 1.58 4.91 .302 Proportion Of interactions with family .04-1 .276 .225 .357 .284 .210 .144 Proportion Of interactions with friends 0-.75 .353 .229 .211 .197 .469 .189 # of different activities 0-20 5.80 1.88 5.56 2.01 6.00 1.84 .333 .636 # of relationships—total number of relationships indicated across the social logs # of different types of relationships—number of different types of relationships indicated across the social logs Proportion of interactions with family—number of interactions with family / total number of relationships Proportion of interactions with friends—number of interactions with friends / total number of relationships 5 WIAT Discourse includes the Vending Machine and Rollercoaster tasks (Cronbach’s alpha=.7633) Picture Description is coded 1 if the respondent mentioned the relationship between the boys and 0 if they did not. 6 14 Figure 1 15 Table 2 Bivariate correlations for language tasks, cognition and education BNT WIAT Picture Composite 7 Discourse description Cognistat WIAT Discourse .264 Picture description .250 -.290 Composite Cognistat .582** .557* .069 Education .806*** .262 .302 ** * + .625** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). Correlation is significant at the 0.10 level (2-tailed). 7 WIAT Discourse includes the Vending Machine and Rollercoaster tasks (Cronbach’s alpha=.7633). 16 Table 3 Bivariate correlations among social variables # of logs Setting # of different Proportion of Proportion of types of interactions interactions relationships w/family w/friends Setting .471* # of different types of relationships .581** .566** Proportion of interactions w/family -.486* -.745*** -.795*** Proportion of interactions w/friends .477* .499* .544* -.519* # of different activities .513* .377 .648** -.582** .220 ** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). * Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). + Correlation is significant at the 0.10 level (2-tailed). 17 Table 4 Bivariate correlations for all variables BNT WIAT Picture Composite Education # of logs Setting # of different Proportion of Proportion of Discourse8 description Cognistat types of interactions interactions relationships w/family w/friends WIAT Discourse .264 Picture description .250 -.290 Composite Cognistat .582** .557* .069 Education .806*** .262 .302 .625** # of logs .489* .321 .450* .567** .482* Setting .600** .540* .314 .427+ .390+ .471* # of different types of relationships .658** .438+ .209 .522* .517* .581** .566** Proportion of interactions -.535* w/family -.458* -.214 -.548* -.333 -.486* -.745*** -.795*** Proportion of interactions w/friends .490* .472* .107 .639** .576** .477* .499* .544* -.519* # of different activities .358 .129 .600** .192 .121 .513* .377 .648** -.582** .220 ** Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). * Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). + Correlation sis significant at the 0.10 level (2-tailed). 8 WIAT Discourse includes the Vending Machine and Rollercoaster tasks (Cronbach’s alpha=.7633). 18 Figure 2 # of interactions with family members by setting 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 N= 2 9 Unprogrammed Programmed Setting 19 Table 5 Partial correlations controlling for education9 WIAT Composite # of logs Setting # of different Proportion of Proportion of # of Discourse Cognistat types of interactions interactions different 10 relationships w/family w/friends activities -.005 BNT WIAT Discourse Composite Cognistat .169 .194 .525* .476* -.477* .054 .444+ .521* .230 .493* .366 -.407+ .407+ .102 .389 .255 .298 -.462* .437+ .151 .351 .442+ -.394+ .279 .523* .462* -.710** .365 .361 -.771*** .351 .690** -.425+ -.579** # of logs Setting # of different types of relationships Proportion of interactions w/family Proportion of interactions w/friends ** * + 9 .186 Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed). Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level (2-tailed). Correlation sis significant at the 0.10 level (2-tailed). Picture description not included because it is a dichotomous variable. WIAT Discourse includes the Vending Machine and Rollercoaster tasks (Cronbach’s alpha=.7633). 10 20 Table 6 OLS regression results (standardized coefficients) with BNT as dependent variable, controlling for education Education (1= more than high school) Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4 Model 5 .806*** .636*** .706*** .783*** .674*** .329* # of different relationships -.299* Proportion of interactions with family .039 Proportion of interactions with friends .338* Setting R2 R2 change .650 .729 .079 .729 .079 .651 .001 .746 .096 F F-change 33.363*** 22.861*** 4.981* 22.889*** 5.000* 15.827*** .050 24.990*** 6.473* + p<.10, * p<.05, **p<.01, ***p<.001 21 Table 7 OLS regression results (standardized coefficients) with WIAT Discourse11 as dependent variable, controlling for cognition Composite Cognistat Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4 Model 5 .557* .451+ .437+ .431 .399+ .202 # of different relationships -.218 Proportion of interactions with family .197 Proportion of interactions with friends .370+ Setting R2 R2 change .310 .339 .029 .343 .033 .333 .023 .422 .112 F F-change 8.079* 4.368* .764 4.438* .860 4.238* .584 6.198** 3.289+ + p<.10, * p<.05, **p<.01, ***p<.001 11 WIAT Discourse includes the Vending Machine and Rollercoaster tasks (Cronbach’s alpha=.7633). 22 Table 8 Logistic regression results with the Picture Description as dependent variable12 Model 1 # of different activities B Exp(B) B Exp(B) .987* 2.682 .834+ 2.302 .054 1.055 # of logs LR chi-square + Model 2 8.687** .720 p<.10, * p<.05, **p<.01, ***p<.001 12 Picture description is coded 1 if the respondent mentioned the relationship between the two boys and 0 if they mentioned both boys, but not the relationship. 23 References Antonucci, T. C. (1990). Social supports and social relationships. In R. Binstock, L. K George (eds.), Handbook of Aging and the Social Sciences (3rd ed ed., pp. 205-226). San Diego: Academic Press. Au, R., Joung, P., Micholas, M., Obler, L., Kass, R., Albert, M. (1995). Naming ability across the adult life span. Aging and Cognition, 2(4), 300-311. Bassuk, S.S., Glass, T. A., & Berkman, L. F. (1999). Social disengagement and incident cognitive decline in community-dwelling elderly persons. Annals of Internal Medicine, 131(3), 165-173. Borod, J., Goodglass,H. & Kaplan, E. (1980). Normative data on the Boston Diagnostic Aphasian Examination, Parietal Lobe Battery, and the Boston Naming Test. Journal of Clinical Neuropsychology, 2, 209-215. Burke, D. L., L. (1981). Memory and aging: the role of retrieval processes. Psychological Bulletin, 90, 512-554. Carstensen, L., Gross, J. & Fung, H. (1997). The social context of emotional experience. In K.W. Schaie & M.P. Lawton (eds.), Annual review of gerontology and geriatrics: Focus on emotion and adult development (Vol. 17, pp. 325-352). New York: Springer. Crohan, S. & Antonucci, T. (1989). Friends as a source of social support in old age. In R.G. Adams & R. Blieszner (eds.) Older adult friendship: Structure and process. Newbury Park: Sage. Drane, D., Yuspeh,R., Huthwaite,J., Klingler,L., Foster, L., Mrazik, M. & Axelrod, B. (2003). Healthy older adult performance on a modified version of the Cognistat(NCSE): Demographic issues and preliminary normative data. Journal of Clinical and Experimental Neuropsychology, 25(1), 133-144. Fingerman, K. B., K. (2003). Do age differences in close and problematic fmaily networks reflect variation in living relatives? Journals of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 58B(2), P80. Kemper, S., Kynette, D., Rash, S., O'Brien, K., Sprott, R. (1989). Life-span changes to adults' language: Effects of memory and genre. Applied Psycholinguistics, 10, 49-66. Kemper, S. S., A. (2001). The structure of verbal abilities in young and older adults. Psychology and Aging, 16(2), 312-322. Nezlek, J., Richardson, D., Green, L., Schatten-Jones, E. (2002). Psychological wellbeing and day-to-day social interaction among older adults. Personal Relationships, 9, 57-71. 24 Reis, H. W., L. (1991). Studying social interaction with the Rochester Interaction Record. In Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 24, pp. 269-318). ?: Academic Press. Rook, K. (2003). Exposure and reactivity to negative social exchanges: A preliminary investigation using daily diary data. Journlsl of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences, 58B, P100-P111. Ryan, E. B. (1995). Normal aging and language. In R. Lubinski (ed.), Dementia and communication. San Diego: Singular. Seeman, T. E., Lusignolo, T. M., Albert, M., & Berkman, L. (2001). Social relationships, social support, and patterns of cognitive aging in healthy, high-functioning older adults: MacArthur studies of successful aging. Health Psychology, 20(4), 243-255. Zunzunegui, M., Alvarado, B., Del Ser, T., and Otero, A. (2003) Social networks, social integration, and social engagement determine cognitive decline in community-dwelling Spanish older adults. Journals of Gerontology: Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 58B(2), S93-S100. 25 26