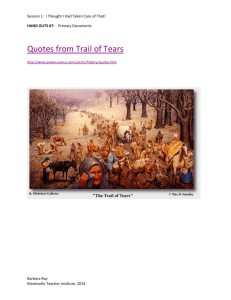

Trail of Tears: Rebecca Neugin & John G. Burnett I n the American

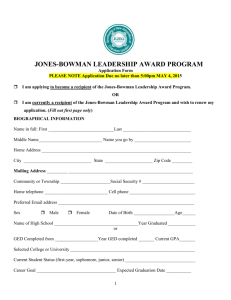

advertisement

"Take time to deliberate; but when the time for action arrives, stop thinking and go in." – Andrew Jackson Trail of Tears: Rebecca Neugin & John G. Burnett I n the American Revolution, the Cherokee people had fought on the side of the British. Badly beaten, their villages and crops burned, the Cherokee signed a treaty with the new United States government in 1789. In the treaty the Cherokees agreed to remain peacefully on their lands in parts of Georgia, Tennessee, and Alabama and not make war against the United States. In return, the United States agreed that no white person could come into the lands of the Cherokee Nation without permission. Then in 1829, gold was discovered on the land of the Cherokee. White settlers began to pour into the territory in violation of the treaty. President Andrew Jackson supported the white settlers. He asked Major Ridge Congress to move the Cherokee out of Georgia and Alabama to land that would be set aside for them west of the Mississippi River. And so, even an American Indian people who had complied with the United States policies were eventually betrayed. In January of 1830, Cherokee warriors, led by Major Ridge, gave the white settlers an ultimatum: “We will give you time to pack your belonging and get out.” As the whites rode off, they looked back to see their cabins in flames. White people throughout Georgia were angry. Bands of whites began to ride about the Cherokee country, shooting at Native Americans and setting their houses on fire. Major Ridge and the other Cherokee chiefs had to make a decision about whether to stay on their land which they had lived for generations or leave. The United States Government finally persuaded some of the Cherokee leaders, including Major Ridge, to sign the Treaty of New Echota. In the treaty, the Cherokee agreed to give up all their lands east of the Mississippi River in exchange for lands in Oklahoma plus $5 million. Major Ridge at the time said that he was signing his own death warrant. Many whites and Cherokees protested against the treaty. Nevertheless, it was approved by the Senate of the United States in 1836. 1. Complete the chart below. Reasons for Cherokee to Stay Reasons for Cherokee to Leave F ederal soldiers and Georgia state militias began to force the Cherokee from their homes. Settlers waited to seize their homes and possessions as soon as they were out of their houses. The Cherokee were held prisoner in camps until the move to the West began. It was a time of great sadness and distress for the Cherokee. Many of the Cherokee were forced to march all the way to Oklahoma on foot. The march began in October, 1838. It was a rainy autumn, and the roads were muddy. The people carried heavy loads, even the old people. They did not have enough food or medicine. Many Cherokee people died, especially children and the elderly. The forced march became known as the Cherokee Trail of Tears. Nearly one fifth of the Cherokee people died on the march to Oklahoma, plus and uncounted number of slaves owned by the Cherokee. After moving to Oklahoma, Major Ridge was murdered by a group of Cherokee who were angry that he had signed the Treaty of New Echota. The United States Government never paid the Cherokee people the $5 million it promised in the Treaty of New Echota. Imagine you are a lawyer for the Cherokee Nation trying to prove that the U.S. government knowingly committed genocide against several Native American tribes on the East Coast using the information above and the eyewitness testimony of Rebecca Neugin and John G. Burnett 2. What is our definition of genocide? 3. Complete the chart below citing evidence which leads you to believe this was genocide. Source Text: Rebecca Neugin: John G. Burnett Evidence Rebecca Neugin was three years old when she made the trip west with her parents. Her account, recorded in 1932, is based largely on information given to her by her family. W hen the soldiers came to our house my father wanted to fight, but my mother told him that the soldiers would kill him if he did and we surrendered without a fight. They drove us out of our house to join other prisoners in a stockade. After they took us away, my mother begged them to let her go back and get some bedding. So they let her go back and she brought what bedding and a few cooking utensils she could carry and had to leave behind all of our other household possessions. My father had a wagon pulled by two spans of At the time of her death in 1932, she was the last oxen to haul us in. Eight of my brothers and remaining survivor of the Trail of Tears sisters and two or three widow women and children rode with us. My brother . . . , who was a good deal older than I was, walked with a long whip which he popped over the backs of the oxen and drove them all the way. My father and mother walked all the way also. The people got so tired of eating salt pork on the journey that my father would walk through the woods as we travelled, hunting for turkeys and deer which he brought into camp to feed us. Camp was usually made at some place where water was to be had and when we stopped and prepared to cook our food, other emigrants who had been driven from their homes without the opportunity to secure cooking utensils came to our camp to use our pots and kettles. There was much sickness among the emigrants and a great many little children died of whooping cough. John G. Burnett, a private in the United States Army who was very troubled about what he witnessed during the Cherokee removal, gave his recollections: B eing acquainted with many of the Indians and able to speak their language, I was sent as interpreter into the Smoky Mountain Country in May, 1838, and witnessed the execution of the most brutal order in the history of American warfare. I saw the helpless Cherokees arrested and dragged from their homes, and driven at the bayonet point into the stockades. And in the chill of a drizzling rain on an October morning I saw them loaded like cattle or sheep into 645 wagons and started towards the west. One can never forget the sadness of that morning. Chief John Ross led in prayer and when the bugle sounded and the wagons started rolling many of the children rose to their feet and waved their little hands good-by to their mountain homes, knowing they were leaving them forever. Many of the helpless people did not have blankets and many of them had been driven from home barefooted. On the morning of November the 17th we encountered a terrific sleet and snow storm with freezing temperatures and from that day until we reached the end of the fateful journey on March the 26th, 1839, the sufferings of the Cherokees were awful. The trail of the exiles was a trail of death. They had to sleep in the wagons and on the ground without fire. And I have known as many as 22 of them to die in night of pneumonia due to ill treatment, cold, and exposure. Among this number was the beautiful wife of Chief John Ross. This noble hearted woman died a martyr to childhood, giving her only blanket for the protection of a sick child. She rode thinly clad through a blinding sleet and snow storm, developed pneumonia and died in the still hours of a bleak winter night. General Scott issued the following proclamation on May 10, 1838: “Cherokees! The President of the United States has sent me, with a powerful army, to cause you, in obedience to the Treaty of 1835, to join that part of your people who are already established in prosperity, on the other side of the Mississippi. . . . The full moon of May is already on the wane, and before another shall have passed away, every Cherokee man, woman and child . . . must be in motion to join their brethren in the far West.” Federal soldiers and Georgia state militias began to force the Cherokee from their homes. Settlers waited to seize their homes and possessions as soon as they were out of their houses. The Cherokee were held prisoner in camps until the move to the West began. It was a time of great sadness and distress for the Cherokee. Many of the Cherokee were forced to march all the way to Oklahoma on foot. The march began in October, 1838. It was a rainy autumn, and the roads were muddy. The people carried heavy loads, even the old people. They did not have enough food or medicine. Many Cherokee people died, especially children and the elderly. The forced march became known as the Cherokee Trail of Tears. Nearly one fifth of the Cherokee people died on the march to Oklahoma, plus and uncounted number of slaves owned by the Cherokee. After moving to Oklahoma, Major Ridge was murdered by a group of Cherokee who were angry that he had signed the Treaty of New Echota. The United States Government never paid the Cherokee people the $5 million it promised in the Treaty of New Echota.