Innovations in humanitarian response

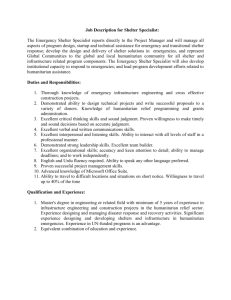

advertisement