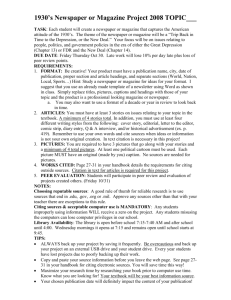

Petty 1 Auburn Petty Layout & Design Michael Gouge Due: April 23

advertisement

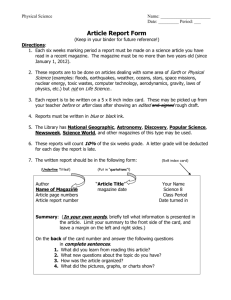

Petty 1 Auburn Petty Layout & Design Michael Gouge Due: April 23, 2013 Proposal for amplified. I. GOAL The publication amplified. is aimed toward a 18- to 24-year old demographic; gender and biological sex are not an issue for the target audience because the publication is not aimed toward a particular gender. These readers are likely college students with a lower income, so advertising and content will be tailored to that demographic. These readers are passionate about music; they are generally open-minded, opinionated and outspoken. The readers are avid social media users, so the publication will have active social media accounts, including Facebook, Twitter and Instagram. These accounts will be used to connect with readers and promote online content as well as the print product. The age of social media and the internet in general created a generation of media consumers that feel entitled to partake citizen journalism, which creates some issues for actual media organizations. However, the purpose of amplified. is to entertain, persuade and inform readers. The publication sets out to inform readers about new releases, tour dates, etc, while also giving an opinion on the quality of those new releases. The publication also sets out to entertain readers, using artistic design, with the hope of making every page something that a reader would want to hang on his or her bedroom wall. In addition to the artistic entertainment value, amplified. Petty 2 content will employ humor and tasteful sarcasm in its content, which will appeal to the demographic. This communication is needed in the market because independent voices are lost in music media. Even other music publications like Under the Radar, which used to feature artists who actually fell “under the radar” and went unnoticed, have begun to spotlight musicians who are already gaining plenty of attention from bigger media like Spin and even Rolling Stone. Readers need this kind of communication, and also, smaller musicians need this kind of coverage. The music scene is saturated by artists who are producing albums from their bedrooms. Now, more than ever, music media is necessary to help listeners weed through the horrible music to find the undiscovered gems left in the industry. II. STRATEGY The content of amplified. will come from my portfolio. All photography, articles and graphics will be elements I have already created or will create specifically for this publication. The final product will sample multiple kinds of content: an album review, a show review and a photo corner. The goal of this publication is to have wall-worthy art on nearly every page, which means that every article will have at least one accompanying photo, and each page will definitely have a dominant element. The publication will be in a magazine format because as discussed in class, younger demographics prefer smaller publications, like tabloids or magazines, as opposed to broadsheet newspapers. Magazines generally use higher-quality glossy paper, which lends itself to wall art more than average newsprint. Magazine layout lends itself to more creativity, as “the grid” and modular design are not as strictly enforced. However, because of that, it could be easy to get carried away with design and create ineffective layouts. Petty 3 The magazine will feature strong dominant elements and display heads for the main features of the magazine. The main font family will be Helvetica Neue, ranging from a bold face to the ultra light face, as Helvetica is popular with the younger demographic, which amplified. hopes to target. The publication will also use a limited collection of specialty fonts for display heads. The publication will feature large images with shorter accompanying articles, as the young demographic is fast-paced and too busy for long articles; this is the Twitter generation, so shorter, concise articles are more likely to be read than full-blown evaluations. III. LITERATURE REVIEW In The Newspaper Designer’s Handbook, Harrower suggests the key to a successful design is a dominant element to “visually anchor the page” (Harrower, 2008, p. 85). Having one, clear dominant image has a greater impact on a reader than cluttered, similar-sized images because good design emphasizes what’s important (Harrower, 2008, p. 84). Successful designs also feature balanced and scattered images, or else the design becomes confusing because it “distracts us and intrudes into stories where it doesn’t belong,” or it creates a “lopsided” effect, in which the graphic elements “clump together in one part of the page and text collects in another” (Harrower, 2008, p. 85). He also suggests that all stories should be rectangular (modular) and graphic elements should vary in size (Harrower, 2008, p. 84). According to The Elements of Graphic Design, there are seven major design components: unity, gestalt, space, dominance, hierarchy, balance and color (White, 2002, p. 57). Unity means that “all elements are in agreement” (White, 2002, p. 57), and White suggests that unity is the ultimate goal of design in general. Gestalt is the cumulative meaning of design, which is to say that all of the parts of a design contribute to a whole, greater meaning (White, 2002, p. 59). “Gestalt is the over-all quality being described when you say, ‘This design works’” (White, Petty 4 2002, p. 59). According to White, when designing, it is important to think about space and to “think of displacing the emptiness with pictures, display and text type, and graphic embellishments like rules. Stay conscious of the remaining empty areas and use it to guide, attract, and arouse the viewer to become engaged” (White, 2002, p. 63). Dominance is “created by contrasting size, positioning, color, style or shape” (White, 2002, p. 63). White suggests it is important to organize elements in a hierarchical manner because “the best design moves the reader across the page in order of the type and the images’ significance” (White, 2002. p. 63). Balance can be symmetrical or asymmetrical; asymmetrical design requires skilled use of white space and implies modernism, while symmetrical balance is easier and implies formality (White, 2002, p. 65). Finally, White suggests that skilled use of color can aid organization, gives emphasis to important elements and provides direction for the reader (White, 2002, p. 65-67). In Cullen’s Graphic Design That Works, he points out that “as a magazine reader, you never see a grid, (but) the grid helps define the format of the magazine – its overall look and feel” (Cullen, 2006, p. 97). Cullen discusses simple and complex grids. Simple grids contain only a few different text or graphic elements, and as more elements are added, the more complex the grids become. “Designers often rely on simple grids and work creatively within them” (Cullen, 2006, p. 99). However, Samara’s Making and Breaking the Grid, design does not always require a grid. “Grid structure in typography and design has become a part of the status quo of designing, but as recent history has shown, there are numerous other ways to organize information and images” (Samara, 2002, p. 119). Sometimes, content doesn’t require a grid, and sometimes, a designer can just choose to ignore the so-called “rules of design,” as long as the choices are tasteful. “Sometimes the content needs to ignore structure altogether to create specific kids of Petty 5 emotional reactions in the intended audience;sometimes a designer simply envisions a more complex intellectual involvement on the part of the audience as a part of their experience of the piece” (Samara, 2002, p. 119). Lupton’s Thinking with Type discusses the importance of typography in design. Although the standard text size on most computers defaults to 12 point font, 9 to 11 point fonts work best for printed text because text sizes more than 11 point appear “clunky” (Lupton, 2004, p. 37). Lupton suggests that alignment is important, and furthermore, each choice for text alignment has positive and negative aspects. “Justified text makes a clean, figural shape on the page. Its efficient use of space makes it the norm for newspapers and books of continuous text;” however, Lupton also argues that “ugly gaps can occur as text is forced into lines of even measure,” so it is important to be mindful when using justified text (Lupton, 2004, p. 84). Lupton also discusses the grid, and he argues “endless variations are possible” within the grid. In Johnson and Prijatel’s The Magazine from Cover to Cover, they suggest “the cover is the most important editorial and design page in a magazine. The cover, as the magazine’s face, creates that all-important first impression” (Johnson & Prijatel, 2013, p. 275). Their research concluded that photos sell better than artwork. There are multiple options for cover designs, but this project employs the “multitheme, one image” approach. “In a multitheme, one-image cover, there are multiple cover lines, but just one image. Most desiners believe that the image grabs the reader’s attention first, but it’s the multitheme aspect of different cover lines that clinches the sale” (Johnson & Prijatel, 2013, p. 279). Samara’s Publication Design Workbook outlines the importance of all elements of design – not just the journalistic text, but also the graphics, photos, headlines, etc (Samara, 2005, p. 22). “The manipulation of images adds communication to that which is readily apparent from their Petty 6 subjects. On a more abstract level, color, shape and illustrative treatment all contribute to a publication’s overall message, and can be considered content in their own right” (Samara, 2005, p. 22). Although sometimes images and graphics can stand alone, Samara points out that “most publications rely on imagery to supplement their written content (Samara, 2005, p. 23). IV. WORKS CITED Cullen, C. D. (2006). Graphic design that works: Secrets for successful logo, magazine, brochure, promotion, and identity design. Gloucester, Mass: Rockport Publishers. Harrower, T. (2008). The newspaper designer's handbook. (6th ed.). New York, NY: McgrawHill. Johnson, S., & Prijatel, P. (2013). The magazine from cover to cover. (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Petty 7 Oxford University Press. Lupton, E. (2004). Thinking with type, a critical guide for designers, writers, editors, & students. New York: Princeton Architectural Pr. Samara, T. (2002). Making and breaking the grid: A graphic design layout workshop. Beverly, Mass: Rockport Publishers. Samara, T. (2005). Publication design workbook: A real-world design guide : magazines, newspapers, catalogs, annual reports, newsletters, literature systems, and everything in between. Gloucester, Mass: Rockport Publishers. White, A. W. (2002). The elements of graphic design, space, unity, page architecture, and type. Allworth Pr.