IMMIGRATION LAW

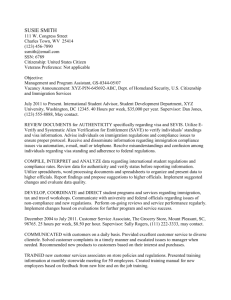

advertisement