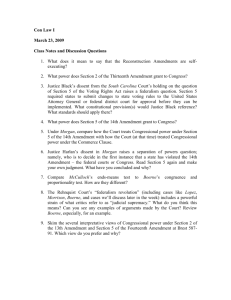

Con Outline 5 - Valparaiso Student Bar Association

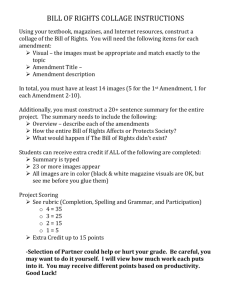

advertisement