Pick your moment - Journalism.co.za

advertisement

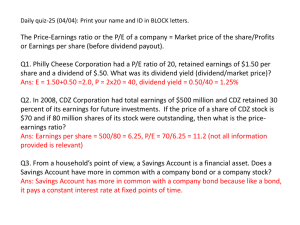

06 October 2006 ASSET CLASSES: EQUITIES Pick your moment By Stafford Thomas Value from equities depends on the assumptions you are making Few asset classes can match equity when it comes to capital growth and protection against inflation. An investor with a portfolio that did no more than match the JSE's industrial & financial index (Findi) over the past 30 years would have enjoyed an average total return of 20,5%/year, easily beating the average inflation rate of 10,6%/year. Equity's big advantage is that the profit growth of companies is linked to the growth of the economy itself. Yet tales abound of self-inflicted disasters experienced by people who have bought at the top of a wave and sold at the bottom. At the heart of these stories of woe are two human influences: greed and fear. WHAT IT MEANS Don't just hope for the best: do the maths Beware earnings that have been abnormal Failure results from a lack of understanding of the basics. This can apply to those investing directly in shares or by way of unit trusts. The objective of equity investors is to hold back or sell when value wears thin, but before the risk/reward odds have swung against them. Conversely, they will want to shrug off the fear factor and be on the prowl when individual shares offer value. As one of the most astute of all equity investors, Warren Buffett, founder of US investment company Berkshire Hathaway, put it: "Be fearful when others are greedy and greedy when others are fearful." But determining "value" is the trick. It is not an easy process and can be undermined by wrong assumptions. Professional fund managers' views are based on reasoned assumptions, however, and there is no reason why informed private investors cannot do the same. At the heart of determining value is the expected return on a share, a market sector or the market as a whole. Returns are a function of changes in an index's level, or a share's price, plus dividends. The Findi's average return over 30 years was, for example, made up of capital gains of 16,6%/year and dividends yielding 3,9%/year. In the case of a share, dividend yield is its annual dividend payment divided by its price. Using the Findi as an example of assessing value, the first step is to estimate the sustainable rate of growth of its underlying dividends and earnings. The Findi's dividends and earnings are based on the average of its composite companies, weighted in terms of their market capitalisation. Headline earnings per share (HEPS) are used and are derived from profit after tax, adjusted for nonrecurring costs and profits. After the past few years of strong earnings growth - 22,7%/year from the Findi between January 2004 and September 2006 - the temptation is to assume it will continue. But this growth rate was well in excess of long-term norms, and far exceeded the 9,9%/year growth of SA's nominal (not adjusted for inflation) gross domestic product (GDP). Over the past 30 years nominal GDP growth averaged 13,3%/year and Findi earnings growth a lower 12%/year. In real, after-inflation terms, the Findi's 19%/year earning growth rate since 2004 has also been exceptional and compares with real growth of only 1,5%/year over 30 years. Looking ahead over the next three years, do you make a gung-ho or a conservative estimate of earnings (and dividend) growth? The gung-ho school is forecasting average Findi earnings growth of about 15%/year. But a conservative investor wary of the greed trap may want to step back and take a more measured view. This may be wise, given the dangers presented by a yawning currentaccount deficit that depends heavily on volatile foreign equity investment inflows for finance. Rising interest rates in a consumer sector borrowed to the hilt add more uncertainty. Let's assume that fund managers are correct when they warn that profits of many companies are way above sustainable levels, and that growth in earnings and dividends is about to subside towards GDP growth. This is in line with the thinking of a fund manager such as Piet Viljoen of Re:CM, who believes that over time EPS growth will be closer to nominal GDP growth. In terms of government's growth initiative, real GDP growth averaging 4,5%/year between 2006 and 2009 can be hoped for. Add inflation at 5%/year, and nominal GDP growth would be 9,5%/year. Could earnings and dividend growth revert to this? Quite possibly. Earnings growth is far from stable and over the past 10 years has varied, on a year-on-year basis, from a negative 13,2% in 2003 to 28,3% in 2005. The mean was 9,4%/year. The implications of an average 9,5%/year earnings growth for the Findi's value take the investor to the next step of value assessment. This is the concept of the present value (PV) of an estimated index level or share price, at a point in the future. Indeed, the PV approach forms the basis for all investment decisions, be they property developments or new mining ventures. Put simply, the PV is calculated by taking an asset's estimated value at a point in the future, and then discounting it back to the present using a chosen discount rate. For example, if an asset is expected to have a value of R100 in three years' time, its current price must be no more than R75 - if a return of 10%/year is sought. For equities, a PV estimate entails selecting a risk-free benchmark, and then a risk premium that comes with exposure to the higher risk posed by an equity investment. The benchmark is simple: government bond yields. The risk premium depends on risk aversion levels, and based on the current thinking of fund managers, it is 4%-6% above government bond yields. So, using the 6% hurdle and the R153 bond's yield of 8,7%, if earnings grow at 9,5%/year over the next three years, a minimum return of 14,7%/year will be required for equity to be a more attractive investment than bonds. But this is a static picture; markets are dynamic. In the present environment of rising interest rates, the conservative investor may want to plug a higher bond yield into a PV calculation, say 9%. This, plus a risk premium of 6%, gives a required minimum return of 15%/year from the Findi. Next, a view must be taken on share prices relative to their earnings in three years' time. This is the price:earnings ratio, or p:e, and is calculated by dividing a share's price by its headline EPS. P:e ratios are among the trickiest of the moving targets facing investors (see also FM Fox). Highly volatile, they are driven by factors as diverse as current and expected interest rates, expected earnings growth and, the most slippery of all, market sentiment. Quote: At the heart of investment stories of woe are two human influences: greed and fear Over the past 10 years the Findi's trailing (historic) p:e has ranged from 8,6 in February 2003 to 20,5 in April 1998, with a mean of 14,2. At present the p:e is 15,6, which is above the mean and therefore viewed as stretched, even by some optimistic fund managers. Put in perspective, the Findi is trading at the same p:e as the UK's FTSE 100 index, and thus appears to offer little by way of an emerging-market risk premium. This has prompted managers such as Allan Gray's Arjen Lugtenburg to comment: "By global standards, all SA asset classes are no longer cheap." Asian emerging-market shares, for instance, offer far better value. Again, this may prompt a cautious investor to opt for a less aggressive p:e - the 14,2 mean in calculating the Findi's PV. Assuming earnings growth of 9,5%/year and a 14,2 p:e at the end of three years, the Findi would stand at a level of 24 450 in three years' time, up 18% from its current 20 750. But discounted at 15%/year, its PV comes in at 17 450. This would make the Findi almost 19% overvalued. This calculation includes dividends that are also assumed to grow at 9%/year and discounted back at 15%. Right or wrong, a view on this mix of variables is implicit whenever an equity investment is made. If not, the investor is merely hoping for the best. However, it is useful to test a valuation using more optimistic assumptions. For instance, using the current 15,6 p:e, the high end of earnings and dividend growth forecasts 15%/year - and applying a discount of 12,7% (the low-end 4% risk premium plus the R150's 8,7% yield) puts the Findi's PV at 23 554, or 12% undervalued. Looked at another way, at its current level, the Findi offers fair value if a 15%/year increase in earnings and dividends is assumed, its p:e stays at 15,6 and a discount rate of 13,7%/year (the R150's 8,7% plus 5% risk premium) is used. Ultimately, the astute investor will buy when the PV based on conservative assumptions screams out "value", as the Findi did in 2003. But even based on optimistic assumptions, value is not abundantly evident at present. This does not mean that value is not to be found among individual shares. Here, some of the steps followed by Buffett are instructive. "Put a heavy weight on certainty," he advises. One of his key criteria is that a company must have a significant position in its markets. As an indicator of ability to perform in good times and bad, he also demands a solid track record as a listed company. Quote: As an indicator of a stock's ability to perform in good and bad times, Buffett also demands a solid track record as a listed company Sound financial metrics are also vital, such as EPS and dividend growth, return on equity (RoE), operating margins and cash flow. These indicate which way a business is heading, and should have been in upward trend for five years. Though no single metric is a perfect measure of fundamentals, RoE is one of the most valuable. It is derived by dividing headline earnings by average shareholders' funds. It highlights whether a firm is using investors' money efficiently. A company's RoE should be high both in absolute terms and relative to its peers. But beware of RoEs that appear abnormal. Retailer Edcon, up from 17,3% in 2003 to 42% in 2006, is a good example. It is unsustainable, says Lugtenburg. Another factor to consider is a firm's use of borrowings. High debt levels can enhance RoE, but could also leave it vulnerable when interest rates rise. Cash flow must also be given careful attention. EPS can be manipulated; cash generated cannot. A useful measure is cash flow after tax, but before dividend payments. Cash flow per share that is persistently below headline EPS should set red lights flashing. A good example of a share meeting the criteria of high RoE, operating margins in the ascent, a robust balance sheet and strong cash flow is IT firm EOH. Buffett highlights other, more subtle criteria worth pondering. Your goal as an investor, he stresses, should be to buy, at a rational price, shares of an easily understandable business whose earnings are virtually certain to be materially higher five, 10 and 20 years from now. As for where to look, Buffett told Berkshire Hathaway shareholders: "I read annual reports of the company I'm looking at and I read the annual reports of the competitors - that is the main source of material."