When does the Attorney client relationship end

advertisement

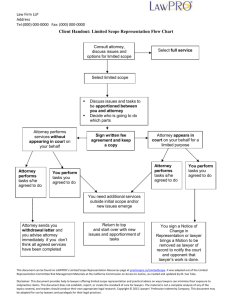

Fundamental Attorney-Client Ethical Issues in the Legal Aid Context Patricia A. Wrona 11/14/08 I. Who is the client? Legal aid attorneys should be sure to deal with the person who has the legal problem. Sometimes determining who is the client, or should be the client, can be difficult. There are no Illinois Supreme Court rules that exactly tell us who the client is. That’s an assumption the rules make, that you know who your client is. The establishment of an attorney/client relationship is seen from the client’s, not the attorney’s, perspective. Did the client believe he was seeking and receiving professional advice or information? If so, an attorney client relationship is established. That is why written retainer/representation letters or agreements (even irrespective of the issue of fees) are very important. It states clearly who is your client, who you are working for. Examples for Illustration: --Helpful third parties making first contact with the attorney (friend, family) --legal representatives of the client (power of attorney agent; guardians) --parents II. Dealing with Multiple Parties Clients (as non-attorneys) do not understand that their legal interests are not exactly the same as someone else who they consider close to them (spouse, boyfriend, child, parent). Clients need to be informed that the attorney can only represent one of them if there is any diversity of interest between them. If it is a situation where the two have an affinity of interest and no diversity of interest, both may be represented, but should be asked to sign a waiver that should a diversity of interest arise, where the attorney cannot continue to represent them both, they understand that one (or both) of them may have to get an different attorney. Ill. Rule of Prof. Conduct 1.7. Conflict of Interest: General Rule *** (c) When representation of multiple clients in a single matter is undertaken, the disclosure shall include explanation of the implications of the common representation and the advantages and risks involved. 1 Examples for illustration: --husband and wife concerning a foreclosure or other debt --parent and adult child in an eviction matter III. Communications in the Presence of Third Parties Clients are often insistent that conversations with the attorney take place in the presence of third parties (spouse, sibling, friend). This is often for purposes of moral support or “so I remember everything you told me.” Such practice should be avoided as it voids the attorneyclient privilege, and clients must be told that, and should even sign a waiver acknowledging that you have advised them it waives the privilege. If the matter is in or may lead to litigation, the substance of the conversation might become the subject of discovery due to the waiver of the privilege because of the presence of a third party. Information voluntarily disclosed by a client to an attorney in the presence of a third party who are not agents of the client or attorney is not privileged information. In re Himmel, 125 Ill. 2d 531 (1988)(mother and fiancé of client present). This is because any communication made in the presence of a third party is inconsistent with the notion that a communication was ever intended to be confidential. Collins v. Utley, 332 Ill. App. 258, 75 N.E.2d 36 (2d Dist. 1947). A client who chooses to hold a communication in the presence of third parties, such communication ceases to be confidential and is not entitled to the protections usually afforded to attorney/client communications. Collins, supra. Attorneys should get the client’s express permission to discuss their legal matter with any third party, whatever the relationship. Examples for illustration: --wife/client brings husband along with her to divorce desk --client brings friend to help at a legal consultation IV. Limitation of Scope of Legal Services Clients generally expect that any attorney has “taken on” their matter or case, so anything less than a full representation where the attorney is handling all aspects of the matter for the client must be disclosed and agreed to by the client. This is a particular challenge for hotlines, and limited court desk legal services. Ill. R. of Prof. Conduct 1.2. Scope of Representation *** (c) A lawyer may limit the objectives of the representation if the client consents after disclosure. 2 For any limitation of the legal services (retained just for purposes of negotiation, or settlement, or just drafting of documents, or for just one court appearance), the client should be informed of the limits of the attorney’s services, and should sign a written disclosure that they understand and acknowledge the limitations of the attorney’s services. Further, the depth or length of services do not change the ethical obligations the attorney owes to a client. While there may be no appearance on file, the ethical obligations of confidentiality and conflicts of interest still are joined. Examples for illustration: -- telephone hotlines --limited service court based desks --out of court representations with adversaries --in court representations V. Death of a Former Client and the attorney-client relationship The death of a former client does not terminate the attorney’s professional obligations to him, including for conflict of interest purposes. The death of the client does not terminate client loyalty or confidentiality, though death is said to terminate the attorney-client relationship in the same manner as the attorney being fired by the client, the attorney withdrawing from representation, or the matter for which the attorney was retained is now ended. Rule 1.9 of the Illinois Rules of Professional Responsibility governs conflicts of interest with former clients: “[a] lawyer who has formerly represented a client in a matter shall not thereafter: (1) represent another person in the same or a substantially related matter in which that person’s interests are materially adverse to the interests of the former client, unless the former client consents after disclosure….” Case law provides that when a client dies, that event in general terminates the attorneyclient relationship for purposes of the attorney’s authority to act on the client’s behalf. In re Horwitz, 371 Ill. App. 3d 625, 863 N.E.2d 842 (1st Dist. 2007)(death of client terminates attorney-client relationship, and attorney must obtain authorization of decedent’s personal representative in order to pursue interests of the decedent any further); Clay v. Huntley, 338 Ill. App. 3d 68, 787 N.E.2d 317 (1st Dist. 2003); In re Marriage of Fredericksen, 159 Ill. App. 3d 743, 512 N.E.2d 1080 (2d Dist. 1987). While the attorney-client relationship ends at death (just as it would with the termination of the working relationship through either the attorney being fired, or the attorney withdrawing, or even the matter for which he was retained being concluded), the duties of loyalty and confidentiality continue forever. 3 The Illinois Supreme Court has held that the duty of loyalty (which is at the heart of the conflicts of interest rules) does not terminate with the client’s death. In re Michal, 415 Ill. 150, 112 N.E.2d 603 (1953)(death of the former client did not release attorney from duty of loyalty owed to client)(citing ABA Opinion 64 (1947)). The death of the client does not discharge the attorney’s duty of loyalty, nor does it free the attorney to represent adverse interests. In re Williams, 57 Ill.2d 63, 309 N.E.2d 579 (1974)(attorney who did so censured). The duty of confidentiality also does not terminate on the death of the client. In re Busse, 332 Ill. App. 258, 75 N.E.2d 36 (2d Dist. 1947)(attorney could not be compelled to testify concerning conversations with now deceased client). Example for illustration: --client who received legal advice concerning her house; after her death adult child/heir/executor seeks to consult about the estate VI. When A Client Threatens Violence When a client threatens violence in an otherwised privileged communication with the attorney, the attorney has a duty to disclose, and certainly a right, to reveal confidences in order to prevent death or serious bodily harm. Illinois Rule of Professional Conduct 1.6(b) provides that “a lawyer shall reveal information about a client to the extent it appears necessary to prevent the client from committing an act that would result in death or serious bodily harm.” (Emphasis added). Further, Rule 1.6(c) provides that “a lawyer may use or reveal …the intention of a client to commit a crime in circumstances other than those enumerated in Rule 1.6(b)….” (Emphasis added). Under the ABA Model Rules of Professional Conduct, Rule 1.6 is similar to the Illinois Rule 1.6, but gives the attorney discretion to reveal this type of information: “(b) A lawyer may reveal information relating to the representation of a client to the extent the lawyer reasonably believes necessary: (1) to prevent reasonably certain death or substantial bodily harm…” ABA Model Rule of Prof. Conduct 1.6(b) (emphasis added). In the comments to the rule, the ABA noted that: Although the public interest is usually best served by a strict rule requiring lawyers to preserve the confidentiality of information relating to the representation of their clients, the confidentiality rule is subject to limited exceptions. Paragraph (b)(1) recognizes the overriding value of life and physical integrity and permits disclosure reasonably necessary to prevent reasonably certain death or substantial bodily harm. Such harm is reasonably certain to occur if it will be suffered imminently or if there is a present and substantial threat that a person will suffer such harm at a later date if the lawyer fails to take action necessary to eliminate the threat. …. 4 Comment 6, Rule 1.6, Legal Ethics Law Deskbook, Prof. Resp. Rule 1.6 (2006-07 ed). The ABA rule generally conforms with tort law on duty to disclose threats of a crime. See e.g. Tarasoff v. Regents of Univ. of Calif., 17 Cal. 3d 425, 131 Cal. Rptr. 14, 551 P.2d 334 (1976)(where psychotherapist knew of his patient’s planned murder, psychotherapist was liable in tort when he did not take steps reasonably necessary under circumstances, such as notifying the police, or the victim). Attorneys are in a similar situation, and may even have a heightened duty when the threat concerns other officers of the court, because “…attorneys, as officers of the court, have a duty to warn of true threats to harm members of the judiciary communicated to them by clients or by third parties.” State v. Hansen, 122 Wash. 2d 712, 721, 862 P.2d 117, 122(1993)(defendant had made threat against a judge during the defendant's conversation with an attorney whom he was attempting to retain, such threat was not protected by attorney-client privilege). See also Marc L. Sands, The Attorney’s Affirmative Duty to Warn Foreseeable Victims of a Client’s Intended Violent Assault, 21 Tort & Ins. L.J. 355 (1986); Davalene Cooper, The Ethical Rules Lack Ethics: Tort Liability When A Lawyer Fails to Warn a Third Party of a Client’s Threat to Cause Serious Physical Harm or Death, 36 Idaho L. Rev. 479 (2000). Thus, under the Illinois rule, and also under the ABA, an attorney has a duty to disclose, and certainly a right, to reveal confidences in order to prevent death or serious bodily harm. Balla v. Gambro, 145 Ill. 2d 492 (1991)(in-house corporate attorney vowed to his corporate client to do “whatever necessary” to prevent sale of client’s adulterated kidney dialyzers could reveal corporate confidences to prevent death or serious injury to end user patients). Examples for illustration: --client states “I am going to kill this judge!” --client states “I am going to blow everyone up.” VII. New Developments of Interest to Legal Aid Attorneys A. Effective on July 1, 2008, Illinois Supreme Court rules were amended to allow retired and inactive attorneys, as well as corporate attorneys, the ability to provide pro bono services (such as through LSPs). This change allows retired, inactive and in house attornesy who have a limited admissions status to provide pro bono work, without charge or any expectation of a fee, to individual so limited means or charitable groups. Such attorneys must provide these services btrough the auspices of a sponsoring entity, which is a “not for profit legal services organization, …law school clinical program or bar association providing pro bono services.” They must register their participation, with the ARDC on an annual basis, and participate in any trainings required by the sponsoring entity. Ill. Sup. Ct. Rule 716 (limited admission of house counsel) now allows in house counsel licensed under this rule to offer legal services “as provided in Rule 756(j).” Ill. Sup. Ct. Rule 756 (Registration and fees) provides in subsection (j) as follows: (j) Pro Bono Authorization for Inactive and Retired Status Attorneys and House Counsel. 5 (1) Authorization to Provide Pro Bono Services. Notwithstanding the limitations on practice for attorneys who register as inactive or retired as set forth in Rule 756(a)(5) or (a)(6), or for attorneys admitted as house counsel pursuant to Rule 716, such an attorney shall be authorized to provide pro bono legal services under the following circumstances: (a) without charge or an expectation of a fee by the attorney; (b) to persons of limited means or to organizations, as defined in paragraph (f) of this rule; and (c) under the auspices of a sponsoring entity, which must be a not-for-profit legal services organization, governmental entity, law school clinical program, or bar association providing pro bono legal services as defined in paragraph (f)(1) of this rule. (2) Duties of Sponsoring Entities. In order to qualify as a sponsoring entity, an organization must submit to the Administrator an application identifying the nature of the organization as one described in section (j)(1)(c) of this rule and describing any program for providing pro bono services which the entity sponsors and in which retired or inactive lawyers or house counsel may participate. In the application, a responsible attorney shall verify that the program will provide appropriate training and support and malpractice insurance for volunteers and that the sponsoring entity will notify the Administrator as soon as any attorney authorized to provide services under this rule has ended his or her participation in the program. The organization is required to provide malpractice insurance coverage for any retired or inactive lawyers or house counsel participating in the program. To continue to qualify under this rule, a sponsoring entity shall be required to submit an annual statement verifying the continuation of any programs and describing any changes in programs in which retired or inactive lawyers or house counsel may participate. (3) Procedure for Attorneys Seeking Authorization to Provide Pro Bono Services. An attorney registered as inactive or retired or admitted as house counsel who seeks to provide pro bono services under this rule shall submit a statement to the Administrator so indicating, along with a verification from a sponsoring entity or entities that the attorney will be participating in a pro bono program under the auspices of that entity. The attorney’s statement shall include the attorney’s agreement that he or she will participate in any training required by the sponsoring entity and that he or she will notify the Administrator within 30 days of ending his or her participation in a pro bono program. Upon receiving the attorney’s statement and the entity’s verification, the Administrator shall cause the master roll to reflect that the attorney is authorized to provide pro bono services. That authorization shall continue until the end of the calendar year in which the statement and verification are submitted, unless the lawyer or the sponsoring entity sends notice to the Administrator that the program or the lawyer’s participation in the program has ended. (4) Renewal of Authorization. An attorney who has been authorized to provide pro bono services under this rule may renew the authorization on an annual basis by submitting a statement that he or she continues to participate in a qualifying program, along with verification from the sponsoring entity that the attorney continues to participate in such a 6 program under the entity’s auspices and that the attorney has taken part in any training required by the program. (5) Annual Registration for Attorneys on Retired Status. Notwithstanding the provisions of Rule 756(a)(6), a retired status attorney who seeks to provide pro bono services under this rule must register on an annual basis, but is not required to pay a registration fee. (6) MCLE Exemption. The provisions of Rule 791 exempting attorneys from MCLE requirements by reason of being registered as inactive or retired shall apply to inactive or retired status attorneys authorized to provide pro bono services under this rule, except that such attorneys shall participate in training to the extent required by the sponsoring entity. B. There is currently a proposal for an amendment to the Illinois Rules of Professional Conduct (Proposed Rule 6.5) that would mirror ABA Model Rule 6.5 concerning conflicts of interest when an attorney is providing limited services. The Illinois rules may be changed to allow an attorney to provide limited legal services as long as he is not aware of a conflict of interest for himself, or of a member of his firm that would create an imputed conflict of interest. Proposed Illinois Rule 6.5: Nonprofit and CourtAnnexed Limited Legal Services Programs (a) A lawyer who, under the auspices of a program sponsored by a nonprofit organization or court, provides short-term limited legal services to a client without expectation by either the lawyer or the client that the lawyer will provide continuing representation in the matter: (1) is subject to Rules 1.7 and 1.9(a) only if the lawyer knows that the representation of the client involves a conflict of interest; and (2) is subject to Rule 1.10 only if the lawyer knows that another lawyer associated with the lawyer in a law firm is disqualified by Rule 1.7 or 1.9(a) with respect to the matter. (b) Except as provided in paragraph (a)(2), Rule 1.10 is inapplicable to a representation governed by this Rule. 7