STATEMENT OF FACTS

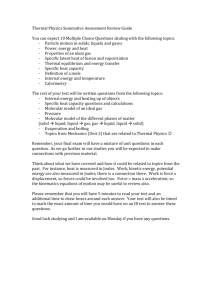

advertisement