CITIES Listing Criteria for Keystone Species by Annie Horner

advertisement

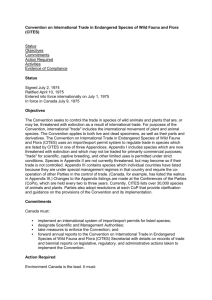

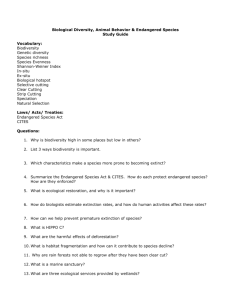

THE FUTURE OF CITIES: CREATING LISTING CRITERIA FOR KEYSTONE SPECIES Annie M. Horner I. INTRODUCTION Despite treaties and other legislation, illegal trade in wildlife and wildlife parts continues to thrive around the world.1 A recent estimate suggests that illegal wildlife trade is worth ten billion dollars annually.2 While efforts have been made to halt this illegal trade, additional attempts must be made to address this global concern.3 The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) governs international trade in wildlife.4 Although CITES provides a framework for protection of many species, changes must be made to adequately protect certain species.5 This comment considers the functionality of CITES in protecting endangered species of plants and animals.6 More specifically, this comment will discuss the history and organization of 1 United States Announces Global Coalition, Including Nonstate Parties, Against Wildlife Trafficking, 100(2) THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF INTERNATIONAL LAW 466, 466 (2006). 2 Id. Only illegal trade in arms and drug smuggling surpasses the amount of illegal wildlife trade. The Coalition Against Wildlife Trafficking: Partners in the Fight Against Illegal Wildlife Trade (September 19, 2006), available at http://www.state.gov/r/pa/scp/2006/72926.htm. 3 Id. For example, In July 2005, at the initiative of the United States, G-8 Leaders recognized the devastating effects of illegal logging on wildlife and committed to help countries enforce laws to combat wildlife trafficking. The Coalition on Wildlife Trafficking will focus its initial efforts on Asia, a major supplier of black market wildlife and wildlife parts to the world. Id. 4 See generally infra Part II. 5 See generally infra Part IV.B.II. 6 See generally infra Parts II, III, and IV. CITES in Part II.7 Part III will consider the weaknesses and other concerns with the Convention and Parties to the Convention.8 Finally, Part IV suggests that a special focus be placed on the protection of keystone species.9 II. BACKGROUND OF CITES Concern for endangered species of flora and fauna has not always been prevalent around the world.10 Nevertheless, in the 1960s, international discussion of conservation in wildlife trade led to the beginnings of CITES.11 In 1963, members of the World Conservation Union drafted a resolution that ultimately resulted in CITES.12 Parties to the Convention agreed on the text in 1973, and the treaty went into force in July of 1975.13 Currently, 173 countries are members of CITES.14 The CITES preamble states: The Contracting States, Recognizing that wild fauna and flora in their many beautiful and varied forms are an irreplaceable part of the natural systems of the earth which must be protected for this and the generations to come; Conscious of the ever-growing value of wild fauna and flora from aesthetic, scientific, cultural, recreational and economic points of view; Recognizing that peoples and States are and should be the best protectors of their own wild fauna and flora; Recognizing, in addition, that international co-operation is essential for the protection of certain species of wild fauna and flora against over-exploitation through international 7 See infra Part II. 8 See infra Part III. 9 See infra Part IV. Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, “What is CITES?” http://www.cites.org/eng/disc/what.shtml. 10 11 Id. 12 Id. Id. Eighty countries met in Washington, D.C. on March 3, 1973 to agree on the Convention text. Id. “The original of the Convention was deposited with the Depositary Government in the Chinese, English, French, Russian and Spanish languages, each version being equally authentic.” Id. 13 14 Id. Membership in CITES is voluntary. Id. Oman joined CITES as the 173rd Party on March 19, 2008. Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, “New Party to CITES,” http://www.cites.org/eng/news/party/oman.shtml. 2 trade; Convinced of the urgency of taking appropriate measures to this end; Have agreed as follows [to the Articles.]15 Conflicting conservationist and preservationist tones exist in the preamble to the Convention.16 A. CITES APPENDICES I, II AND III Article I of the CITES text provides definitions for the Convention.17 Following the definitions, Article II discusses the fundamental principles of the Convention.18 More specifically, Article II sets out the organization of the three Appendices of CITES.19 Article III sets out the regulation of trade for species in Appendix I, Article IV sets out regulations for Appendix II, and Article V sets out regulations for Appendix III.20 “A specimen of a CITES-listed species may be imported into or exported (or re-exported) from a State party to the Convention only if the appropriate documentation has been obtained and presented for clearance at the port of entry or exit.”21 15 Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, pmbl., Mar. 3, 1973, 27 U.S.T. 1087, 993 U.N.T.S. 234, available at http://www.cites.org/eng/disc/text.shtml#texttop [hereinafter “CITES”]. 16 Saskia Young, Contemporary Issues of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) and the Debate over Sustainable Use, 14 COLO. J. INT'L ENVTL. L. & POL'Y 167, 168 (2003). “The text of CITES does not embrace one singular philosophy, preservationist or conservationist, in its approach to protecting endangered species from international wildlife trade. [FN11] In this manner, the CITES text allows the Parties to argue which method is the most desirable to achieve the goal of wildlife protection.” Id. at 16869. 17 See CITES, supra note 15 at art. I. 18 Id. 19 Id. 20 Id. Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, “How CITES Works,” http://www.cites.org/eng/disc/how.shtml. 21 3 Species protected under CITES receive Appendix I, Appendix II, or Appendix III status.22 Appendix I provides the strictest protection for the species of flora and fauna threatened with extinction; these species may only be traded in very rare situations.23 Species of flora and fauna in Appendix II may not be near extinction but need trade regulation to ensure that trade does not threaten each species’ survival.24 Appendix III species are protected when one or more countries requests that CITES assist in regulating trade of a particular species.25 According to the Convention text, “Appendix I shall include all species threatened with extinction which are or may be affected by trade.”26 Trade in species protected by 22 Id. Appendix I includes species threatened with extinction. Trade in specimens of these species is permitted only in exceptional circumstances. Appendix II includes species not necessarily threatened with extinction, but in which trade must be controlled in order to avoid utilization incompatible with their survival. This Appendix contains species that are protected in at least one country, which has asked other CITES Parties for assistance in controlling the trade. Changes to Appendix III follow a distinct procedure from changes to Appendices I and II, as each Party’s is entitled to make unilateral amendments to it. See CITES, supra note 15 at art. II; Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, “How CITES Works,” http://www.cites.org/eng/disc/how.shtml. 23 See CITES, supra note 15 at art. I. Species protected by Appendix I include the red panda (Ailurus fulgens), many species of whales, Laelia lobata and other species of orchids, non-domesticated chinchillas and many other species. Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, Appendices I, II and III, http://www.cites.org/eng/app/appendices.shtml. Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, “How CITES Works,” http://www.cites.org/eng/disc/how.shtml. Appendix II includes species such as the queen conch (Strombus gigas), the Chinese cobra (Naja atra), the great white shark (Carcharodon carcharias), and fire corals (Milleporidae spp.). Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, Appendices I, II and III, http://www.cites.org/eng/app/appendices.shtml. 24 Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, “How CITES Works,” http://www.cites.org/eng/disc/how.shtml. Appendix III species include the Indian grey mongoose in India (Herpestes edwardsi ), walrus in Canada (Odobenus rosmarus), the two-toed sloth in Costa Rica (Choloepus hoffmanni), and poppies in Nepal (Meconopsis regia). Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, Appendices I, II and III, http://www.cites.org/eng/app/appendices.shtml. 25 26 See CITES, supra note 15 at art. II. Animals protected under Appendix I include specimens both living and dead, “readily recognizable parts and derivatives of species.” Id. at Art. I. See also Randi E. Alarcon, The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species: The difficulty in Enforcing CITES and the United States Solution to Hindering the Illegal Trade of Endangered Species, 14 N.Y. INT’L L. REV. 105, 109 (2001). 4 Appendix I requires a prior grant and an export permit, an import permit or a re-export permit.27 CITES only permits trade in Appendix I species in exceptional circumstances and for strictly non-commercial purposes.28 Listing of a species in Appendix I bans all commercial trade of that protected species.29 Species listed in Appendix II typically do not require the same level of protection as Appendix I species.30 Appendix II species, however, do need trade restrictions in order to maintain population levels.31 Regulation of Appendix II species occurs under the permit system.32 Trade is permissible with a valid permit and the approval of the exporting country’s scientific authority.33 No import requirement is required for trade in Appendix II species.34 If the Scientific Authority of the country determines that trade in 27 See CITES, supra note 15 at art. III. An export permit is only issued if both the Scientific and Management Authority of the country satisfy certain requirements. Id. For example, the country must prove that the export of the Appendix I species “will not be detrimental to the survival of that species,” and that the species “was not obtained in contravention of the laws of that State for the protection of fauna and flora .” Id. Import in Appendix I species is only allowed if trade will be not harmful to the species, “the proposed recipient of a living specimen is suitably equipped to house and care for it[,]” and “specimen is not to be used for primarily commercial purposes.” Id. 28 Mario Del Baglivo, CITES at the Crossroad: New Ivory Sales and Sleeping Giants, 14 Fordham Envtl. L.J. 279, 288 (2003). Exceptions include household specimens, scientific specimens, species bred in captivity, and traveling exhibitions. Note, The CITES Fort Lauderdale Criteria: The Uses and Limits of Science in International Conservation Decision Making, 114 HARV. L.R. 1769, 1774 n.34 (2001) [hereinafter “Fort Lauderdale Criteria”]. 29 Fort Lauderdale Criteria, supra note 28 at 1774. Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, “How CITES Works,” http://www.cites.org/eng/disc/how.shtml. 30 31 Id. 32 See Del Baglivo, supra note 28 at 288. 33 Fort Lauderdale Criteria, supra note 28 at 1774 34 See CITES, supra note 15, art. IV; Note, Elisabeth M. McOmber, Problems in Enforcement of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species, 27 BROOK. J. INT’L L. 673, 680-81 (2002). 5 the species in question must reduced, the Management Authority may limit the number of export permits.35 Unlike species listed in Appendices I and II, Appendix III species are protected mainly by the country of origin.36 Also unlike Appendices I and II, Appendix III has no requirement that the export of the species must not be harmful to the survival of the species.37 However, an exporting permit and a certificate of origin are both required for trade in Appendix III species.38 Every two years, the Parties to the Convention meet to review all three Appendices and to determine what amendments must be made.39 Any extraordinary meetings may be held at the written request of greater than one-third of the Parties.40 Amendments made to Appendices I and II must be ratified by a two-thirds of the Parties present and voting.41 The amendments go into force ninety days after the conference unless a Party makes a reservation to the amendment. 42 35 See CITES, supra note 15, art. IV; McOmber, supra note 34, at 681. 36 See CITES, supra note 15, art. V; Del Baglivo, supra note 28 at 289. 37 See CITES, supra note 15, art. V; McOmber, supra note 34, at 681. 38 See CITES, supra note 15, art. V; Del Baglivo, supra note 28 at 289. 39 See CITES, supra note 15, art. IX; Del Baglivo, supra note 28 at 287. 40 See CITES, supra note 15, art. IX. At meetings, whether regular or extraordinary, the Parties shall review the implementation of the present Convention and may: (a) make such provision as may be necessary to enable the Secretariat to carry out its duties, and adopt financial provisions; (b) consider and adopt amendments to Appendices I and II in accordance with Article XV; (c) review the progress made towards the restoration and conservation of the species included in Appendices I, II and III; (d) receive and consider any reports presented by the Secretariat or by any Party; and (e) where appropriate, make recommendations for improving the effectiveness of the present Convention. Id. 41 See CITES, supra note 15, art. XV; Del Baglivo, supra note 28 at 287-88. 42 See CITES, supra note 15, art. XV. 6 Although the Parties enter CITES voluntarily, each Party remains legally bound to the Convention under international law.43 III. CITES CONCERNS While CITES may be considered “the most important legal document to promote protection of wildlife to date. . . ,” the Convention has many weaknesses.44 Concerns include the conflicting tones of the CITES document itself, lack of cohesion between Parties, enforcement problems, and conflicting Party motivations.45 The conflicting conservationist and preservationist tones of CITES cause many debates regarding the effectiveness of CITES.46 Conservationists argue that through sustainable use, Parties to CITES will be able to maintain the economic benefit of species while still protecting threatened species.47 Alternatively, preservationists contend that complete trade bans best protect threatened species, with the focus on the inherent value of the species.48 A. CONSERVATION/SUSTAINABLE USE One of the most persuasive arguments for sustainable use is that trade bans increase the market for banned goods.49 When complete trade bans are placed on certain species, poachers 43 See Del Baglivo, supra note 28 at 287. 44 Comment, Dianne M. Kueck, Using International Political Agreements to Protect Endangered Species: A Proposed Model, 2 U. Chi. L. Sch. Roundtable 345, 347 (1995)(internal citations removed). 45 See Alarcon, supra note 26 at 113-15; Young, supra note 16 at 171-86. 46 Young, supra note 16 at 182. 47 Id. 48 Id. Call of the wild - Trade bans and conservation; Wildlife trade, THE ECONOMIST, March 8, 2008 [hereinafter “Call of the Wild”]; see Fort Lauderdale Criteria, supra note 28 at 1777. 49 7 receive much higher prices for that species.50 Additionally, trade bans are often ineffective in halting illegal trade.51 Multiple examples of unsuccessful trade bans question the effectiveness of complete trade bans.52 Conservationists often cite the ban of trade in ivory to support the sustainable use argument.53 CITES listed the African Elephant on Appendix II from 1977 to 1990.54 However, many African countries simply ignored the regulations under Appendix II and rarely prosecuted ivory traders for illegal trade.55 In 1990, Parties to CITES moved the African Elephant from Appendix II to Appendix I, placing a complete trade ban on all ivory goods.56 While the complete ban has greatly increased the elephant populations,57 trade in ivory goods continues.58 Conservationists argue that the benefits of complete trade bans do not outweigh the downfalls.59 50 Call of the Wild, supra note 49. 51 Del Baglivo, supra note 28 at 291 52 Id. 53 Call of the Wild, supra note 49. A sharp increase in ivory seizures in recent years also points to a flourishing trade. Meanwhile, rising wealth in Asia is raising the returns from poaching. Prices have leapt from $200 a kilo in 2004 to $850-900. New ivory is appearing: you can encase your mobile phone in it if you like. Some scientists think poaching may be as prevalent as it was before the original ban. The ivory ban is frequently held up as a prime exhibit for CITES, which many conservationists consider a highly successful agreement. Elephant numbers, according to figures from the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, have been rising by 4% a year in the well-protected populations of southern and east Africa, but in central and west Africa no one knows what is going on. Id. 54 Del Baglivo, supra note 28 at 292. 55 Id. 56 Id. 57 Id. Call of the Wild, supra note 49. San Francisco’s Chinatown is an example of the continuing trade in ivory. Id. ”Up a steep hill, the cheap souvenirs give way to more exotic wares: antique figures carved in the Japanese netsuke style, statues of monkeys and roosters, delicate earrings and necklaces. They are ivory. There are lots of them. And they shouldn't be there.” Id. 58 8 Another conservationist argument contends that the economic returns associated with sustainable use give the Parties an incentive to work with CITES.60 Many countries that are Parties to CITES do not enjoy the same economic stability as the United States or other developed nations.61 Allowing sustainable use of threatened species gives these nations “a way of achieving economic return for expensive conservation efforts.”62 This economic return allows developing nations the opportunity to create jobs related to conservation, while maintaining the species populations.63 Sustainable use also provides a suitable compromise between species protection and the needs of the humans in the area.64 For example, African nations often view elephants as dangerous and destructive animals.65 Allowing the nations to gain economic benefit from the trade of elephants gives the nations more reason to protect elephants at the same time.66 59 See Young, supra note 16 at 183-84. Complete trade bans have yet to be proven as the most effective means of species protection. Call of the Wild, supra note 49. The only certainty is that the official figures do not reflect the extent of poaching. A huge haul of ivory in 2002, the result of the slaughter of between 3,000 and 6,500 beasts, probably came largely from elephants in Zambia. Yet Zambia had reported the illegal killing of only 135 animals in the previous ten years. Call of the Wild, supra note 49. 60 Young, supra note 16 at 182. 61 Id. 62 Id. at 183. 63 Id. at 184. 64 Id. 65 Id. This debate about effectiveness and outcomes has been paralleled by a debate about the philosophical justification for the protection of particular species. Many inhabitants of Western nations regard elephants as “intelligent, awe inspiring beasts” --organisms of great aesthetic and intrinsic value. Many people in the African range states instead see elephants at best as a potential source of hard currency from ivory sales, or at worst as “dangerous killers and destroyers of property.” Fort Lauderdale Criteria, supra note 28 at 1777 (internal citations omitted). A herd of elephants can be extremely dangerous to villages, trampling crops and harming people. Id. 9 B. PRESERVATION/TRADE BANS Preservationists, on the other hand, argue that sustainable use cannot be enforced at an international level.67 Supporters of complete trade bans contend that sustainable use undermines the intent of CITES.68 CITES adopted the precautionary principle to protect threatened species.69 “The precautionary principle ensures that a substance or activity posing a threat to the environment is prevented from adversely affecting the environment, even if there is no conclusive scientific proof linking that particular substance or activity to environmental damage.”70 This principle ensures that species receive the adequate level of protection under CITES, even if scientific data does not prove that the species must be protected.71 Sustainable use undermines the precautionary principle, a fundamental principle of CITES.72 In addition, preservationists contend that sustainable use may not be sustainable in fact.73 Gathering scientific data is both costly and difficult, especially for developing nations.74 If no timely, reliable studies are available, a species may face over-exploitation from use that is not truly sustainable.75 Countries often forgo expensive studies due to economic pressures.76 Also, 66 Id. 67 Id.; see also Call of the Wild, supra note 49. 68 Young, supra note 16 at 185. 69 Id. 70 David Favre, Debate within the CITES Community: What Direction for the Future? 33 NAT. RESOURCES J. 875, 894 (1993) (quoting J. Cameron & J. Abouchar, The Precautionary Principle: A Fundamental Principle of Law and Policy for the Protection of the Global Environment, 14 B.C. INT'L & COMP. L. REV. 1, 2 (1991). 71 Young, supra note 16 at 185. 72 Id. 73 Id. 74 Id. 75 Id. 10 preservationists believe that the focus on the use of each species detracts from the inherent value of a species.77 If countries simply focus on the uses of each species, animals with no important use may be ignored.78 Past trade bans have been successful in protecting threatened species, particularly severely threatened species.79 “Exports of wild birds from four of the five leading bird-exporting countries decreased by more than two-thirds between the late 1980s and the late 1990s as a result of CITES-related trade measures, including an American import ban. Tanzania went from exporting 38,000 birds in 1989 to ten a decade later.”80 However, not all trade bans have effectively stopped trade in threatened species.81 Successful trade bans typically are coupled with an advertising campaign designed to destroy demand.82 C. ADDITIONAL CITES CONCERNS In addition to the conflicting conservationist and preservationist tones of CITES, other problems with the application and enforcement of CITES exist.83 Such problems include: the lack of cohesion between the parties, enforcement concerns, conflicting party motivations, and 76 Id. 77 Id. 78 Id. 79 Call of the Wild, supra note 49. 80 Id. 81 Id. 82 Id. 83 Young, supra note 16 at 173. 11 textual loopholes.84 These concerns highlight the lack of uniformity between the Parties to CITES.85 1. Lack of Cohesion between Parties The lack of uniformity between the Parties to CITES often causes problems.86 Originally, CITES allowed the Parties to utilize different means to implement the treaty as a solution to the differences between the Parties.87 The United States, for example, enacted the Endangered Species ACT (ESA) in 1973 in response to CITES and other international treaties.88 African countries developed a task force in 1994 to apply CITES among the nations.89 Other countries only make small changes to previous policies in order to comply with CITES.90 A serious lack of cohesion between Parties to CITES occurs in enforcing the CITES provisions.91 2. Enforcement Concerns With no centralized enforcement, each CITES Party controls enforcement of the treaty within that country.92 The lack of uniform enforcement puts the success of CITES into the hands of the Parties.93 “[The] tension between state sovereignty and the need for international 84 Id. at 173-82; Note, Ruth A. Braun, Lions, Tigers and Bears [Oh My]: How to Stop Endangered Species Crime, 11 Fordham Envtl. L.J. 545, 564-73 (2000). 85 See Young, supra note 16 at 173-82. 86 Braun, supra note 84 at 564-65. 87 Id. 88 Id. at 565. 89 Id. at 570. 90 Id. at 568-70. For example, Japan has taken many reservations on specific species. Id. at 568-69. The reservations allow Japanese trade in species that would otherwise be illegal to trade. Id. 91 Young, supra note 16 at 174. 92 Id. 12 environmental initiatives is often a barrier to enforcement of international environmental laws.”94 Maintaining the sovereignty of each Party to CITES is crucial to its success, but some consistency is needed also.95 Unfortunately, monitoring species between Parties causes problems when the parties have differing motivations.96 Few countries are willing surrender to the provisions of CITES if the provisions do not suit the country’s objectives.97 3. Conflicting Party Motivations The many Parties to CITES all have different motivations behind protecting threatened species of plants and animals.98 Some countries recognize animal rights to life and the aesthetic value of animals, while other countries focus on animals as a resource for economic gain.99 Developing countries will be unlikely to sacrifice economic growth to protect threatened species.100 Beyond the reality of enforcement, human rights to food and livelihood outweigh the protection of threatened species.101 “The combination of severe poverty with the potential to make vast profits by trading products made from endangered species has prompted many 93 Id. 94 Alarcon, supra note 26 at 115-16. 95 Id. at 116. Species of plants and animals do not remain within the borders of one country. Id. For this reason, species need monitoring beyond political boundaries. Id. 96 Id. 97 Id. 98 Id. Young, supra note 16 at 173. “The CITES community represents a diversity of views concerning wildlife with the reflection of most of the world's ‘political, ethical, religious and cultural differences’ provided by the governments and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) in attendance at a Conference of the Parties.” Id. (internal citations omitted). 99 100 Alarcon, supra note 26 at 117. 101 Id. 13 government officials to look the other way rather than enforcing the provisions of CITES.”102 The text of CITES does not little to stand in the way of Parties who fail to enforce CITES. 103 4. Textual Loopholes The CITES document protects many species of flora and fauna, but the document also contains serious loopholes to total protection.104 The most serious lacking in the text of CITES is that no central enforcement agency exists.105 Although each Party’s sovereignty must be considered, CITES mandates no uniformity between the 173 Parties to the treaty.106 The voluntary nature of the convention does not sanction Parties for failure to comply with CITES.107 In addition, Article I to CITES allows any Party may take a reservation to a protected species. 108 A reservation essentially permits that country to continue trade in that species regardless of CITES protection.109 IV. SUGGESTIONS FOR THE FUTURE In the more than thirty years since the enactment of CITES, the Parties have periodically considered the effectiveness of the convention.110 This periodic survey has improved the success 102 Id. 103 Id. 104 Id. at 114. 105 See id. 106 Id. 107 Id. at 115. 108 Young, supra note 16 at 178. 109 Id. Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, “Resolutions,” http://www.cites.org/eng/res/14/14-02.shtml. 110 14 of the treaty by changing the manner in which species are listed.111 The original convention did not provide specific listing criteria.112 The first Conference of Parties (CoP1) in Berne, Switzerland set the listing criteria, the “Berne Criteria,” “to use a combination of biological and trade factors as guidelines for determining in which appendix a species should be listed.”113 While the Berne Criteria did provide some guidance in listing, the criteria allowed too much flexibility.114 A. PREVIOUS SOLUTIONS Since CoP1 in Berne, the Parties to CITES have attempted to further clarify the listing criteria.115 At CoP9, the Parties developed and implemented new listing and delisting criteria as a response to criticism.116 At ninth conference (CoP9), in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, the Parties reevaluated the listing criteria for CITES.117 The listing and delisting criteria was changed to a more scientific method.118 111 Young, supra note 16 at 177. 112 Id. 113 John L. Garrison, The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES) and the Debate over Sustainable Use, 12 PACE ENVTL. L. REV. 301, 312-13 (1994) (internal citations removed). Under the Berne Criteria, “[f]or a species to be listed in Appendix I, biological evidence had to suggest that the species was ‘currently threatened with extinction.’ The Berne Criteria provided that the appropriate biological indicators included population size and geographic range. The strength of the biological evidence required depended on the available evidence concerning trade in the species.” Fort Lauderdale Criteria, supra note 28 at 1775 (internal citations removed). “For Appendix II listings, the same kind of biological evidence used for Appendix I listings had to show that a species ‘might become’ threatened with extinction. However, there had to be stronger evidence of trade than that required for Appendix I listings.” Fort Lauderdale Criteria, supra note 28 at 1775 (internal citations removed). Young, supra note 16 at 177. “The flexibility inherent in these criteria was criticized for making the listing process an inherently subjective one, relying on a Party's values, interests and policies to make a decision.” Id. 114 115 Id. 116 Id. at 188. 15 The [Fort Lauderdale Criteria] changed the Berne Criteria in four key respects. First, the [Fort Lauderdale Criteria] included specific quantitative guidelines for the placement of species in each appendix. Second, the [Fort Lauderdale Criteria] were predominantly based on biology rather than on trade status. Third, the [Fort Lauderdale Criteria] recommended that the parties “downlist” Appendix I species that failed to meet the new quantitative criteria. Finally, the [Fort Lauderdale Criteria] allowed “split-listing,” or the simultaneous listing of one population of a species in Appendix I and another population of the same species in Appendix II.119 The new method of listing also specified that a species should be listed in Appendix I of CITES if trade may affect the species, and the species fits one of four biological categories.120 Downlisting of a species from Appendix I to Appendix II occurs if the species fits into one of the four categories “in the near future.”121 In addition to developing the new criteria for listing species in CITES, the Fort Lauderdale Convention also reconsidered the definitions listed within CITES.122 The Fort Lauderdale Convention added numerical guidelines to the definitions.123 These quantitative guidelines made the Fort Lauderdale Criteria more scientific than the previous criteria.124 Since 117 Id. 118 Id. 119 Fort Lauderdale Criteria, supra note 28 at 1779 (internal citations removed). Id. at 1779-80. The four biological categories include: “that the wild population is small; that the population has a restricted area of distribution; that the population is declining; and that, but for inclusion in Appendix I, the species will satisfy one or more of the previous criteria within five years.” Id. 120 121 Id. at 1780. 122 Id. Id. For example, “[t]he guideline for ‘restricted area of distribution’ is ten thousand square kilometers; for ‘decline’ it is a decrease of fifty percent or more within five years or two generations; and for ‘small wild population’ it is fewer than five thousand individuals.” Id. 123 124 Id. at 1781. 16 CoP9 in Fort Lauderdale, subsequent conventions have considered the effectiveness of the new criteria.125 At CoP11 in Gigiri, Kenya, the Parties created the “Strategic Vision through 2005.”126 In 2004 at CoP13, the Parties extended the Strategic Vision to 2013.127 The first purpose of the Strategic Vision is “to improve the working of the Convention, so that international trade in wild fauna and flora is conducted at sustainable levels.”128 The second purpose is “to ensure that CITES policy developments are mutually supportive of international environmental priorities and take into account new international initiatives, consistent with the terms of the Convention.”129 The Strategic Vision helped the Parties to determine the direction of the treaty and sets specific goals.130 At the most recent conference, CoP13, in the Hague in the Netherlands, the Parties determined the specifics for the current Strategic Vision.131 The Parties intend to focus on issues such as considering the “cultural, social and economic factors” related to conversation of species, “promoting transparency and wider involvement of civil society in the development of conservation policies and practices,” and ascertaining that all Parties use approaches “based on scientific evidence is taken to address any species of wild fauna and flora subject to Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora, “Resolutions,” http://www.cites.org/eng/res/14/14-02.shtml. 125 126 Id. 127 Id. 128 Id. 129 Id. 130 Id. 131 Id. 17 unsustainable international trade.”132 The focus of the vision statement is to expand the current strengths of CITES while ensuring that all Parties follow the regulations set forth in the treaty.133 B. KEYSTONE SPECIES FOCUS While the past modifications to CITES have increased its effectiveness, additional changes must be made.134 The Fort Lauderdale Criteria provided much needed guidance in the listing and delisting species.135 Further modifications must be made to the criteria to protect species in the future.136 1. Importance of Keystone Species A keystone species prevents other species from monopolizing an area, and, therefore, maintains the diversity of all species in the area.137 The current Fort Lauderdale criteria do not protect animals or plants based on the significance of that species in the ecosystem.138 Because of the importance of keystone species in different ecosystems, the Parties to CITES must take special notice of keystone species.139 132 Id. 133 Id. 134 See Young, supra note 16 at 188. 135 Young, supra note 16 at 188. 136 See id. 137 Robert T. Paine, Food Web Complexity and Species Diversity, 100(910) The American Naturalist 65, 73 (1966), http://www.jstor.org/stable/2459379. “Ecologists have learned that certain ‘keystone’ species perform unique and critical roles, and their loss results in a drastic change to the ecosystem. Other species appear to be redundant, in that their roles are shared with others in the system, and the loss of any one appears to have no short-term impact.” Karla, Alderman, The big picture, UNESCO Sources, (July/August 1994) Issue 60. 138 Young, supra note 16 at 188. 139 Paine, supra note 137 at 73. 18 The idea of “keystone species” traces to Charles Darwin’s comparisons of types of grasses.140 Since Darwin, many other scientists have researched keystone species and the affects of such species on surrounding species.141 Dr. Robert T. Paine, a well-known zoologist, coined the term keystone species in the late 1960s.142 Studies of keystone species such as sea otters, fish, and wolves have shown the importance of each species in its respective ecosystem.143 Typically, starfish are recognized as the prime example of a keystone species.144 Keystone species have particular importance in the adjacent food web.145 As a food web member, a keystone species helps to ensure that an ecosystem will remain diverse.146 Studies of marine ecosystems have demonstrated that removal of the top predator causes the ecosystem to lose species diversity.147 Dr. Paine’s studies of keystone species focused on “species of high trophic status whose activities exert a disproportionate influence on the pattern of species diversity in a community.”148 In Paine’s research, the presence of the carnivorous seastar (Pisaster ochraceus), maintained prey species diversity in an intertidal 140 Robert T. Paine, A Conversation on Refining the Concept of Keystone Species, 9 CONSERVATION BIOLOGY 962, 962 (Aug. 1995) [hereinafter “Paine II”]. 141 Id. 142 R.D. Davic, Linking keystone species and functional groups: a new operational definition of the keystone species concept, CONSERVATION ECOLOGY 7(1) (2003) http://www.consecol.org/vol7/iss1/resp11/. 143 Paine II, supra note 140 at 962. Even the prairie grass, Big Bluestem (Andropogon gerardii) is considered a keystone species in its ecosystem. Marty Ross, Banking on the Future, HORTICULTURE, 144 Id. at 963. See infra note 140. 145 Paine, supra note 137 at 71. Id. “The metaphor that [keystone species] are similar to the keystone of an arch is valid, because both species and stone derive their functional importance to the system as a whole from bidirectional interactions with lower energy levels.” Id. 146 Id. “When the top predator is artificially removed or naturally absent . . . , the systems converge toward simplicity.” Id. 147 148 Davic, supra note 142. 19 habitat.149 The keystone species in the study prevented monopolization of important ecosystem resources by a single species.150 This idea of a keystone species focuses on the food web interactions from “top-down regulation.”151 The diversity of an ecosystem provides many important services to all species in the ecosystem and to humans.152 Increased biodiversity of an ecosystem typically leads to increased productivity of the ecosystem.153 Ecosystems with higher diversity also utilize ecosystem resources better than ecosystems with low diversity.154 Ecosystems not only supply the food and habitat to resident species, but also produce “food, fiber, and medicine.”155 In addition, ecosystems provide services that most people do not realize.156 Wetlands and other ecosystems preserve water quality and prevent flooding.157 Other 149 Id. 150 Id. (internal citations removed). Id. Paine’s concept of keystone species includes only predator species. Id. Other studies have considered the idea of keystone species of “prey, competitors, mutualists, dispersers, pollinators, earth-movers, habitat modifiers, engineers, hosts, processors, plant resources, dominant trees,” and many others. Id. 151 Alderman, supra note 128. “Ecosystems are geographically defined groups of organisms along with their physical surroundings. In a simplified ecosystem, plants convert sunshine into food, predators eat the plant-eaters, and microorganisms process dead matter into soil.” Id. 152 153 Owen L. Petchey, Species Diversity, Species Extinction, and Ecosystem Function, 155(5) THE AMERICAN NATURALIST 696, 696 (2000). 154 Id. 155 Alderman, supra note 128. 156 Id. 157 Id. Wetland ecosystems (swamps, marshes, etc.) absorb and recycle essential nutrients, treat sewage, and cleanse wastes. In estuaries, molluscs remove nutrients from the water, helping to prevent nutrient over-enrichment and its attendant problems, such as eutrophication arising from fertilizer run-off. Trees and forest soils purify water as it flows through forest ecosystems. In preventing soils from being washed away, forests also prevent the harmful siltation of rivers and reservoirs that may arise from erosion and landslides. 20 services include climate stabilization, pest control, and income generation.158 Diverse ecosystems also have inherent aesthetic value.159 Unfortunately, humans typically do not realize the importance and value of these types of ecosystem services until the services are no longer available.160 Biologists do not fully understand the link between biodiversity and ecosystem health.161 However, decades of studies have shown that the loss of a keystone species in an ecosystem leads to dramatic changes in the ecosystem.162 Because keystone species plays a special role in the ecosystem, the removed of such a species leads to serious ecosystem changes.163 Keystone species are not “redundant” species, meaning that keystone species do not perform the same services as another species in the ecosystem.164 Because no other species have the same role as the keystone species in the ecosystem, the loss of a keystone species has long-term impacts on the ecosystem.165 2. Protection of Keystone Species Unfortunately, species protection often amounts to “emergency-room” conservation, protecting only species nearing extinction.166 Due to the increased importance of keystone The United Nations Development Programme, What is Biodiversity? available at http://www.undp.org/biodiversity/biodiversitycd/bioImport.htm [herinafter “Biodiversity”]. 158 Biodiversity, supra note 157. 159 Id. 160 Id. Unfortunately, restoring degraded ecosystems can be very difficult and costly. Id. 161 Id. 162 Id. 163 Id. 164 Id. 165 Id. 21 species, CITES and other environmental legislation must protect these species.167 Studies have shown that keystone species play a pivotal role in ecosystem function.168 However, CITES does not currently provide special protection for keystone species.169 The CITES listing criteria looks to some biological factors such as the species population size but does not consider keystone species.170 Other legislation has specially protected keystone species in the past.171 The Keystone Species Conservation Act of 1999 aimed to provide keystone species legal protection.172 This Act along with the Great Ape Conservation Act of 2000 went before the United States Congress in June of 2000.173 While both acts were proposed with good intention, only the Great Ape Conservation Act cleared Congress.174 The Keystone Species Conservation Act did not address appropriately distinguish a keystone species from endangered or threatened species and was tabled before enactment.175 166 L. Scott Mills et al., The Keystone-Species Concept in Ecology and Conservation, 43(4) BIOSCIENCE 219, 222 (1993). 167 Alderman, supra note 128. 168 See infra Part IV.B.1. 169 See infra Part IV.A. 170 Id. 171 Davic, supra note 142. 172 Id. 173 Testimony of Jamie Rappaport Clark, Director, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Department of the Interior, Before the House Committee on Resources, Subcommittee on Fisheries, Conservation, Wildlife and Oceans, Regarding H.R. 4320, The Great Ape Conservation Act of 2000 and on H.R. 3407, The Keystone Species Conservation Act of 1999 (June 20, 2000), available at http://www.fws.gov/laws/Testimony/106th/2000/june20.htm. 174 Environmental News Network staff, A Good Week for Great Apes, CNN.com, October 26, 2000, available at http://archives.cnn.com/2000/NATURE/10/26/great.apes.enn/. 175 Davic, supra note 142. 22 The Parties to CITES should learn from the mistakes of the Keystone Species Conservation Act.176 CITES could amend the listing criteria for the Appendices to protect keystone species.177 However, the listing criteria must clearly define “keystone species” to provide adequate protection.178 If CITES takes a more proactive stance to monitor trade in keystone species, other species will be protected as a result.179 VI. Conclusion In the past few decades, CITES has proven at least partially successful in regulating trade in species of wildlife. However, CITES must continue to evolve to provide species protection into the future. Specific weaknesses, such as textual loopholes must be addressed. In addition, the Parties to CITES must work together to bridge gaps in protection between each Party. CITES needs to protect species before the population of a species reaches a critical level. To do this, the criteria for protecting species must change. Research of keystone species has shown the ecological importance of such species. Protection of keystone species by CITES would not only protect the keystone species but would also protect other species in ecosystem of the keystone species. 176 See id. 177 Id. Id.; Mills, supra note 166 at 222. “Before keystone species become the centerpiece for biodiversity protection or habitat restoration, we must be able to say what is and is not a keystone species.” Mills, supra note 166 at 222. 178 179 See generally Mills, supra note 166 at 222. 23