The Brain - U

advertisement

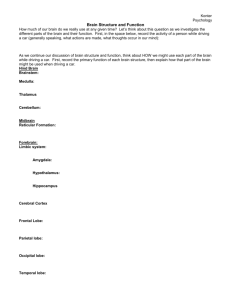

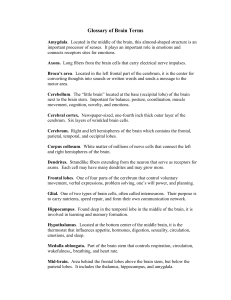

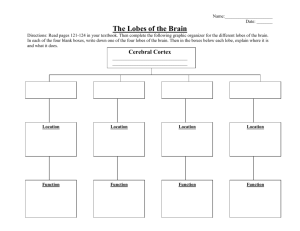

Me & U-First! Module 3 – Intellectual The Brain and Behaviour When the brain is damaged due to a disease process such as Alzheimer's disease, behaviours may change, one may lose control of emotions, and physical abilities can become impaired. Dementia involves the entire central nervous system (CNS) including neurons, glial cells, and neurotransmitters. Different types of dementia may affect different areas of the brain. The areas affected define the symptoms Alzheimer Disease is identified by neurofibrillary tangles & plaques and shrinkage of the brain. Brain cells shrink or disappear and are replaced by dense, irregular-shaped spots or plaques. Thread like tangles appear within existing brain cells, choking healthy cells. A person with AD has less brain tissue with continual shrinkage over time – www.alzheimer.ca.) Each hemisphere or side of the brain contains four lobes. The four lobes, frontal, parietal, occipital and temporal each have different functions, Other parts important to function are the cerebellum, brainstem and hippocampus, at the base of the brain. In order to understand behaviour we will look at areas of the brain affected by Alzheimer Disease and other dementias and the function of these areas The National Brain Tumor Foundation has a diagram of the brain at http://www.braintumor.org/anatomy/ . When you move the cursor over each part of the brain, a box appears indicating for which functions that part of the brain is responsible. Neurotransmitter changes are responsible in part for some of the changes in behaviour of a person with Alzheimer's disease. People with Alzheimer’s disease have low levels of acetylcholine, impairing communication between cells. In addition to reduced acetylcholine, there are a number of other neurotransmitters that affect behaviour: norepinephrine, dopamine, serotonin, and glutamate (see attachment on acetylcholine). Alzheimer’s disease is thought to start in the limbic system and progress through the parietal and temporal lobes. Up to this point, the person may display deficits in skills and require help with complex tasks. Damage to other areas of the brain is associated with more moderately severe Alzheimer’s disease. It is believed that skills are lost in the same order that they are developed. Limbic System Deep within the brain, the limbic system is a group of interconnected structures that mediate emotions, learning and memory. The limbic system connects the frontal and temporal lobes and connects behaviour with memories. Misinterpretations of words and events can occur, resulting in anger, suspiciousness and blaming others, for example, believing that objects are being stolen. This can be challenging for all concerned. The hippocampus, which is vital to memory, is one of the first areas affected by Alzheimer’s disease. - Control of sexuality is thought to be in the limbic system. - Damage in the limbic system can result in emotions that are extreme and changing rapidly. Conversely, the person may appear uninterested or unaffected emotionally by events around them. Any number of emotions can be present, causing the person to become irritable, depressed or anxious. - The limbic system also controls daily functions such as sleeping and appetite, so the person may lose track of when they would normally be awake or sleeping. This may result in the person being awake through the night. - The limbic system includes the hypothalamus, which is responsible for control of body temperature, thirst and appetite. A person with damage in the hypothalamus will feel cold deep in their bones or feel extremely hot. They may experience extreme thirst or appetite. As the limbic system dies, there is emotional instability, inability to control anxiety, rapid switches from states of fearfulness, to restlessness, to irritability to aggressiveness, and eventually to helplessness. Parietal Lobe The parietal lobe is the centre for spatial perception, sensory integration and concentration, affecting the ability to recognize places, objects and people. It also receives and processes information about temperature, taste, touch, and movement coming from the rest of the body. Reading and arithmetic are also processed in this region and it affects ability to concentrate or focus. If the parietal lobe is damaged a person may: become disoriented or lost have problems identifying people and objects experience imaginary visual images (hallucinations) have grand mal or petit mal seizures (10% with dementia) lose ability to recognize parts of body show deterioration in hand skills have deterioration in speech organization and syntax (order of words) not recognize objects by touch Temporal Lobe The temporal lobe is the centre of speech and language control, processes hearing, and is the centre of time awareness. If damaged the person may: have problems finding the right word ask questions repeatedly, lose thought in mid-sentence, speak haltingly, substitute words, repeat words, echo sounds, speak gibberish find that time and seasons become meaningless Occipital Lobe The Occipital Lobe helps process visual information With the loss of peripheral vision, the person may only see straight ahead lose ability to look up lose ability to focus or track on a moving object progressive vision impairment – only distinguish contrasts Motor Cortex The Motor Cortex is responsible for motor function Damage in the Motor Cortex may lead to: - problems initiating and following through with movements - problems swallowing - symptoms that include leaning to the side or forward, muscle weakness, poor balance, muscle cramping, trouble getting up from seated position, feeling of restlessness, problems with gait and posture - hypermetamorphosis – fascination with and picking at small objects - in late stages person curling into fetal position Frontal Lobe The frontal lobe, at the front of our head, behind our forehead, is known as the executive or management centre of the brain; initiation centre; or adult behaviour centre. The frontal lobe is responsible for a number of important functions, which are all affected by Alzheimer Disease. The frontal lobe helps control skilled muscle movements, mood, planning for the future, setting goals, and judging priorities When damaged the person: has diminished social judgement loses critical functions of cognition (thought formation, reasoning, judgement, abstract thinking, and social consequence) becomes totally focussed on personal needs cannot be aware of or feel concern for others is uninhibited in all actions, including sexual activity demands instant gratification With loss of planning ability, a person has difficulty organizing such tasks as getting dressed, planning a meal, getting from home to work, or accomplishing other familiar tasks. The ability to initiate activity may be lost; the person may appear apathetic or uninterested in doing anything, even previously enjoyed activities, such as hobbies. This can be frustrating for families who may believe that the person is unwilling to do things. In contrast, a person with damage to the frontal lobe may be unable to stop doing something, such as rubbing hands together or tapping on a table. This symptom is called ‘perseveration.’ Perseveration can lead to frustration on the part of caregivers if the activity that the person is doing is bothersome. The frontal lobe of the brain is also the regulator for insight and feedback regarding socially appropriate behaviour. Impairment in the frontal lobes can lead to a number of socially challenging events, which may include: verbal outbursts or sexual behaviour inappropriate to the time, person or location. The incorrect feedback from the brain leaves the person unaware of the impact of their actions. Cerebellum The cerebellum in the subcortex controls vital involuntary systems: heart, lungs, diaphragm, and digestive system. When damaged the body begins to shut down. The person experiences irreversible weight loss. Brain and Behaviour - The complexity and combinations of damage and resulting losses can contribute to paranoia, delusions, disorientation, anxiety, fear, loss of willpower, even nausea and feelings of general malaise. Each dementing disease/disorder has its own pattern of progression, producing its own sequence of behaviours. It is important to remember that not all persons with dementia display the same symptoms. Care providers should be able to recognize the difference between the normal aging process and behaviours associated with dementia.