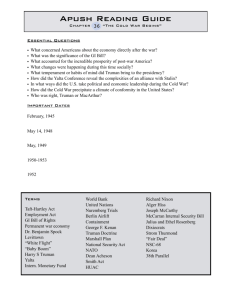

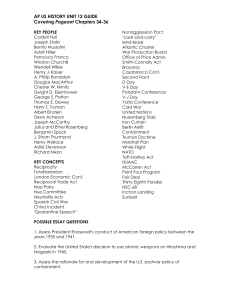

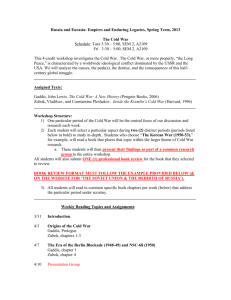

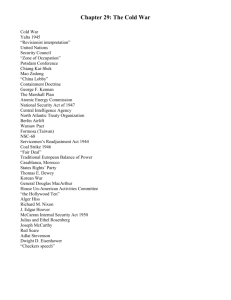

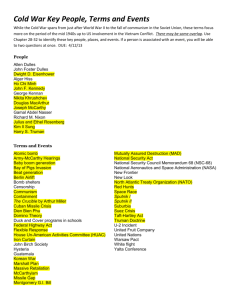

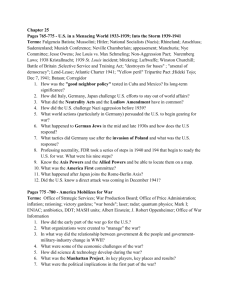

The Cold War: The 4 Policemen, Roll

advertisement