PSY458_SuggsPaper

advertisement

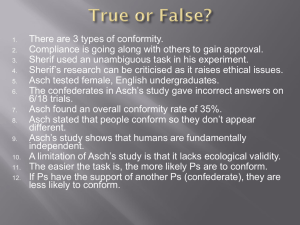

Running head: GROUPS AND CONFORMITY Groups and Conformity Caroline “Carrie” Suggs PSY 458 Dr. Kobek Pezzarossi Running head: GROUPS AND CONFORMITY Whether we realize it or not, conformity is everywhere. Scream “Fire” in a movie theatre and everyone runs in the same direction. If you carefully observe the people trying to decide on a meal while at a busy food court, you'll notice that they're walking in the same direction. Not even animals are immune; chimpanzees share new and unusual behavior patterns with each other (Aronson, Wilson, & Akert, n.d). As a person who tends to go against the crowd, conformity fascinates me. What motivates people to behave in a similar manner? Verbal language is a powerful tool, but we do not give human behavior a sufficient amount of credit. I have always wondered how people would react if a person acted in a manner that was not considered “normal”. For the sake of science, I decided to do an experiment along with research on experiments involving conformity. In order to understand the basics of conformity, we need to examine the two different types of social influences. Informational social influence appeals to us on a cerebral level since it “occurs when we conform because we see other people as a source of information” (Aronson, Wilson, & Akert, n.d.). There are several factors that will serve as a trigger for informational social influence, such as ambiguity (Aronson, Wilson, & Akert, n.d.). People in spontaneous crowds will behave according to the other people in the same crowd, because they recognize that the behavior of the majority is an indicator of appropriate behavior (Mann, 186, p. 181). Informational social influence also occurs if the situation is a crisis (Aronson, Wilson, & Akert, n.d.). From an evolutionary standpoint, we had a better chance of surviving if we mimicked each other and stayed together in a group whenever a predator appeared, because standing out of a crowd makes you more visible to a starving predator with sharp teeth (Griskevicius, Goldstein, Mortensen, Cialdini, Kenrick, 2006, p. 282). Griskevicus et al. (2006) hit the nail on the head when they wrote “Following often leads to better and more accurate decisions, especially when we face uncertainty” (p. 282). Finally, informational social influence occurs when other people are experts (Aronson, Wilson, & Akert, n.d.), because we are more likely to assume that they are the ones who have all of the information. Running head: GROUPS AND CONFORMITY The second type of social influence, normative social influence, occurs as a result of our innate need to be liked and accepted (Aronson, Wilson, & Akert, n.d.). This means that if a person wants to be accepted by a group of people, the person will be driven by normative social influence since “the more the individual is attracted to the group, the more he will conform to its norms” (Kiesler, 1963, p. 559). According to Latane's theory, normative social influence occurs when the group contains three or more people, when the group is important, there are no allies in the group, or when the culture is collectivist (Aronson, Wilson, & Akert, n.d.). Japan is a collectivist culture and it has been found that the Japanese are more likely to resist conformity pressures from strangers while being easily swayed by pressure from family, friends, or colleagues (Mann, 1986, p. 187). Journal articles have attributed the conformity stemming from Asch's conformity study as a result of the subject lacking allies, because disagreement with the consensus could possibly result in social exclusion (Campbell & Fairey, 1989, p. 459). Normative social influence is especially powerful, Griskevicius et al. (2006) found that “normative influence is especially potent because people who deviate from the group are more likely to be punished, ridiculed, and even rejected by other group members” (p. 282). It is possible to speculate that this form of social influence is more powerful, because by nature, humans are social creatures and acceptance is crucial. Conformity can be used as an intentional tool of manipulation. During my research, I stumbled across interesting information about evangelists using the size of the crowd in their favor. Mann (1986) cites a prominent evangelist, Billy Graham, as an example, because while preaching to a crowd, he “skillfully arouses a sense of guilt” in the audience members and they are given the chance to absolve their guilt by coming to the platform and making a “public and therefore committing vow” (p. 174). According to this study, there is a correlationary relationship between the audience size and the commitments made by audience members, since “the larger the crowd the greater the proportion of the membership who will be persuaded to adopt the speaker's recommendation” (Mann, 1986, p. 174). Running head: GROUPS AND CONFORMITY There are a significant number of conformity studies that have been performed by researchers. This paper will examine two different conformity studies, starting with the most well-known and commonly cited conformity study performed by Solomon E. Asch. When Asch started his conformity study in 1952, he intended to “to show that when people were confronted with norms that were clearly 'contrary to the fact,' they would not exhibit conformity” (Campbell & Fairey, 1989, p. 458). The premise of Asch's study involved the test subject being placed in a group of confederates, with the group being shown pictures of lines of varying length (Ross, Bierbrauer, Hoffman, 1976, p. 148). When asked to identify the lines according to length, the confederates purposefully gave the wrong answer as to see how the subject would react in the face of public judgment (Ross, Bierbrauer, Hoffman, 1976, p. 148). To add to the confusion, the participant was always the last person to share his answer (Aronson, n.d.). Imagine you're in the shoes of the extremely baffled subject and being the last one to share your answer, knowing that your answer deviates from the general consensus. Asch found that in this scenario, when the subject was forced to choose between the evidence of his senses and the consensus of his peers, the path of public conformity was often chosen (Ross, Bierbrauer, Hoffman, 1976, p. 148). At the end of Asch's conformity study, it was found that 76 percent of of the participants gave answers that conformed with the majority's answer (Aronson, Wilson, & Akert, n.d.). The participants also took part in post-experimental interviews and they often expressed that they were concerned about appearing foolish in the presence of a group of strangers (Aronson, Wilson, & Akert, n.d.). During one of those post-experimental interviews, a participant said “A lot of them just copied what the other one said... I felt they weren't sure themselves and were just copying” (Gerard, Wilhelmy, Conolley, 1968, p. 79). Asch's conformity study shows normative social influence at work, since the participants of the study were placed in a group containing more than three people and there were no allies to be found in the very same group (Aronson, Wilson, & Akert, n.d.). In Asch's study, the participant was put in an Running head: GROUPS AND CONFORMITY unusual situation where his dissent “represented a challenge to their competence, wisdom, and sanity- a challenge one is loath to offer, particularly when one's own ability to make sense of one's world seems suddenly in question” (Ross, Bierbrauer, Hoffman, 1976, p. 149). Asch found that if the group consisted of one or two confederates, “there was very little conformity” (Latane & Wolf, 1981, p. 442). On the flip side, conformity increased dramatically if the group consisted of three or more confederates (Latane & Wolf, 1981, p. 442). This led Asch to pinpoint three as the “magic” number in cases of conformity (Latane & Wolf, 1981, p. 441). Further studies on conformity also revealed that conformity would increase if the judgments were difficult, complex, or subjective; if the members of the group were attractive, and if the activity was intended to enhance the sense of cohesiveness and/or interdependence in the group (Ross, Bierbrauer, Hoffman, 1976, p. 148). A lesser known study on conformity was done in 1968 by Stanley Milgram, Leonard Bickman, and Lawrence Berkowitz (p. 80). The study was performed as to test the effects of different crowd sizes on passerby (Milgram, Bickman, Berkowtiz, 1969, p. 79). The study took place on two different winter afternoons on a busy sidewalk in New York City and involved 1,424 pedestrians (Milgram, Bickman, Berkowitz, 1969, p. 80). A fifty foot length of sidewalk across the street from an office building was designated as the observation area with a group of confederates of varying sizes stopping to look up at one of the windows on the sixth floor of the office building (Milgram, Bickman, Berkowitz, 1969, p. 80). It is important to note that while the unwitting pedestrians walked by, the confederates stood there and looked at the window for exactly sixty seconds (Milgram, Bickman, Berkowitz, 1969, p. 80). Additionally, the size of the stimulus crowd varied in size, from “1, 2, 3, 5, 10, and 15” (Milgram, Bickman, Berkowtiz, 1969, p. 80). The participants of the study could react in two different ways. Milgram, Bickman, and Berkowitz (1969) wrote “the passerby could simply look up at the building where the crowd was staring without breaking stride, or he could make a more complete imitative action by stopping and standing alongside with the crowd” (p. 80). Running head: GROUPS AND CONFORMITY According to the results of the conformity study, Milgram, Bickman, and Berkowitz (1969) found that “the size of the stimulus crowd significantly affects the proportion of passerby who stand alongside it” (p. 81). A larger number of the test subjects were more likely to partially adopt the crowd's behavior by looking up in the direction of the office's sixth floor without stopping (Milgram, Bickman, Berkowitz, 1969, p. 81). When there was only one confederate looking at the target while standing, only four percent of the passerby stopped, compared to forty percent of pedestrians that stopped when there was a group of fifteen confederates (Milgram, Bickman, Berkowitz, 1969, p. 80). Regarding people who did not stop walking to look at the source of the confederates' attention, a single confederate made forty-two percent passerby look while the presence of fifteen confederates caused “86% of the passerby to orient themselves in the same direction” (Milgram, Bickman, Berkowitz, 1969, p. 81). In the paper, it was theorized that the percentage who looked up without stopping was higher, because it was the less demanding choice, since “the more demanding, in time or effort, the behavior the less likely it is that the passerby will join it” (Milgram, Bickman, Berkowitz, 1969, p. 81). The journal article discussing Milgram, Bickman, and Berkowitz's 1969 study concluded with “There is some logical basis for joining larger crowds: all other things being equal, the larger the crowd, the more likely its members are attending to a matter of interest” (p. 81). In a separate journal article Mann (1986) states that “'a stimulus' crowd of at least five apparently 'interested' bystanders was necessary before naive passerby could be induced to become part of the spectator crowd” (p. 185). To satisfy my innate curiosity, I decided to do an experiment to see if people would be more likely to notice unspoken social cues in a busy setting versus a quieter setting. The basic premise of my experiment was to have my tolerant yet embarrassed confederate stand in a prominent location while pointing to a nonexistent object in the ceiling with an index finger. The reactions of random people walking by my confederate were recorded by keeping a tally count. The way I saw it, the participants of my study would react in one of the three possible ways. First, they could notice my confederate Running head: GROUPS AND CONFORMITY pointing to the ceiling and react by looking up. The experiment subjects could also take the bolder approach by stopping to ask my confederate some questions about his unusual behavior. Or more disappointingly, the unwitting participants would just ignore the social cue while walking past my confederate. The experiment is reminiscent of Asch's study, because they both contain the elements of confusion and uncertainty in a social setting. Additionally, the experiment is similar to the study performed by Milgram, Bickman, and Berkowitz, since it involves testing the reactions of passerby by looking at an uninteresting object while in a public location. The first half of my study took place on a weekday at the Marketplace, a popular location for lunch, at approximately noon during the lunchtime rush. I had my confederate stand in a prominent location, a few feet away from the main stairs leading to and from the Marketplace. The period of observation lasted for approximately fifteen minutes. Measuring the reactions of the group was a challenge, because there were so many people and I had a difficult time keeping track of everyone's reactions. I was fascinated to see that when my confederate started pointing to the ceiling, a significant portion of the crowd looked up. The number of people who looked up continued to increase with time, especially when unaware people started to notice that the other people were looking up. I also was sure to pay special attention of people going down the stairs to the Marketplace. Most of those people looked up to the ceiling after noticing my confederate's pointed finger. Very frequently, those people did a double take by looking at the confederate again and taking another look in the direction of the pointed finger. The second and last half of my study took place in a location known as the G-Area. The G-Area is often less populated. People are more likely to walk through the G-Area instead of making it their destination. I chose to do the experiment at approximately 10:45 in the morning on a weekday, because I knew that there would be a minimal amount of people hanging out in the G-Area. My confederate stood with his finger pointed to the ceiling for approximately ten minutes. Interestingly enough, people Running head: GROUPS AND CONFORMITY were less likely to notice my confederate, so they were less likely to look up at the ceiling. The people who did notice my confederate and look up rarely stopped or broke their stride while doing so. Unlike the Marketplace, I did not see anyone doing a double take by looking at my confederate and the ceiling twice. Before we take a look at the results of my experiment, I must place emphasis on the fact that it was extremely challenging to keep track of everyone's reactions. I was trying to keep an eye on everyone's reactions and that proved to be difficult, because the two locations had more than one people that were on the move. With that mind, let's look at the results of my experiment. According to my notes, I yielded more reactions from the crowd in the Marketplace with more than fifteen people looking up. I only saw one person that actually ignored my confederate's social cue. In contrast, approximately three people looked up when they saw my confederate standing in the G-Area. I actively counted four people who ignored my confederate, including a person who walked approximately two feet past my confederate. As for people who stopped and asked my confederate questions, I only recorded two different instances. The first person to stop and ask questions took place in the Marketplace after he stood there for a good amount of time. The person who stopped my confederate was a close friend of ours and he stopped to ask the confederate if he was okay. The other instance of a person stopping to ask questions took place in the G-Area and it only happened, because the person had been observing my confederate for more than five minutes. While doing my experiment, I noticed that the participants of my study were more likely to seek information by asking their peers. Since the Marketplace was quite crowded, I noticed that most of the people in the group who noticed my confederate almost always started asking each other questions instead of approaching my confederate for further information. A friend came to me after I completed the first half of my experiment and mentioned that she was approached by someone who had walked down the stairs and noticed my confederate and that particular person had asked my friend questions. Running head: GROUPS AND CONFORMITY This also happened when I did my experiment in the G-Area. The very few people that were present chose to turn to each other to ask questions instead of approaching my confederate. This strikes me as odd, considering how the confederate would be the best source of information compared to the other people in the group who are probably just as equally confused. This phenomenon has been described in literature with Campbell and Fairey (1989) writing “With a majority, people attempt to resolve the dilemma by focusing on the others' responses, not on the stimulus itself. A minority's responses are considered deviant from the start, and people increase attention to the stimulus in order to validate the judgment” (p. 459). This proved to be true with the two different crowds that took part in my experiment. Another surprising development occurred when I was doing my experiment. When I was doing the experiment in the Marketplace, my confederate happened to be standing a few feet away from a booth of people selling tickets to an event. I counted four people sitting at the booth; they literally had front row seats during the experiment. After a few minutes of watching my confederate with confusion and bemusement, they all decided to do a very surprising thing. The four seated observers decided to start pointing to the sky too and they continued to do so until my confederate stopped pointing at the sky. This was an unexpected reaction, yet it exemplifies the purpose of my study, which was to study conformity in groups. A similar incident took place when I was conducting my experiment at the GArea. A female had been standing by the small coffee booth and observing my confederate for a few minutes. Her curiosity soon got the best of her and she walked over to my confederate. When she was standing right next to the confederate, she took a good look at the ceiling for a few seconds and started to point towards the ceiling with her index finger. This lasted for approximately thirty seconds before she stopped imitating my confederate to ask him questions. My experiment brought up an additional set of questions. I found myself wondering if the reactions would have been drastically different if the stimulus had been interesting, because “the Running head: GROUPS AND CONFORMITY interest of the scene would likely hold crowd members for a longer period of time, and the crowd would grow to a larger maximum size” (Milgram, Bickman, Berkowtiz, 1969, p. 81). I also found myself wondering about the differences in reactions if the experiment had included an outdoors setting. I am also curious to see if the reactions would have varied if I had used different confederates of differing ages, genders, and races. My experiment brings me to the final stage of my research, the power of majority influence versus the power of minority influence. Traditionally, most of the studies focusing conformity have involved confederates acting as the majority while involving a sole participant (Latane & Wolf, 1981, p. 439). This is consistent with Asch's discovery of the magic number three (Latane & Wolf, 1981, p. 441). The cliché statement about strength being in numbers has proven to be true, since a significant number of the members must establish a pattern of behavior and/or response before it is imitated by others (Mann, 1989, p. 182). “The greater the number of individuals who espouse a position, the better basis they provide for establishing social reality” (Latane & Wolf, 1981, p. 439). The persuasive powers of the majority can also be attributed to the theory that “the greater the number of people advocating a position, the greater are their resources for rewarding those who conform to that position and punishing those who deviate” (Latane & Wolf, 1981, p. 439). Minorities are at a disadvantage regarding majority influence, because they lack size, status, and power (Latane & Wolf, 1981, p. 440). The majority is not always influential, because “empirical evidence has demonstrated that even non-elite minorities (those lacking special expertise or power) can be successful in modifying majority norms” (Latane & Wolf, 1981, p. 439). While doing his conformity study, Asch found that dissent was more likely to be present if the group contained one or two confederates and if there was the presence of a partner who also disagreed with the consensus (Latane & Wolf, 1981, p. 445). Latane and Wolf (1981) found that “a minority has stylistic advantages inversely related to its size. By standing out against the crowd, the minority gains visibility and becomes the source of attention in the group” (p. Running head: GROUPS AND CONFORMITY 440). The minority also has an advantage, because it “forces the attribution that it is confident and committed to its position, As minority size increases, the potential for ostracism and rejection is reduced, resulting in a decrease in perceived confidence and commitment and consequently in influence” (Latane & Wolf, 1981, p. 440). In this aspect, the majority is at a disadvantage, because it lacks “confidence and commitment created by a consistent behavioral style” (Latane & Wolf, 1981, p. 440). Mann (1989) supports this theory by stating “in large crowds, as in small groups, a vocal conspicuous minority can establish and reinforce a standard of conduct” (p. 181). My experiment has shown the influence of a minority on a large group, because my solitary confederate was able to convince a group of a significant number into choosing to look up at the ceiling. My confederate had the advantage of standing out and appearing to be committed to his unconventional position regarding the ceiling (Latane & Wolf, 1981, p. 440). When people are influenced in a social setting, it is more likely to occur because of informational social influence or normative social influence (Aronson, Wilson, & Akert, n.d.). In the case of my experiment, there was no pressure of being accepted or liked so normative social influence was not present. Instead, the subjects of my experiment were motivated by the need for information by turning to each other for possible answers, which indicates the presence of informational social influence. Evidence pointing to the power of group size has been shown in Asch's magic number three (Latane & Wolf, 1981, p. 441) and the assertion that the number five has more power in a social setting (Mann, 1989, p. 185). This was evident in my experiment, because people were more likely to take notice and react if they were a part of a large group of people. The fact that only two people out of approximately 30 people observed were willing to stop and ask questions coincides with the conclusion created by Milgram, Bickman, and Berkowitz (1969) that people were more likely to react by taking the least demanding method (p. 81). Almost all of the people who took part in my study were already doing something and stopping to ask questions would have required additional effort. People are social creatures, relying on others for Running head: GROUPS AND CONFORMITY information or acceptance. The former has proven to be true for my experiment, with a more significant number of reactions being recorded in a large crowd of people compared to a smaller group of people. . A quote worth repeating is “The larger the crowd the more likely its members are attending to a matter of interest” (Milgram, Bickman, Berkowitz, 1969, p. 81). Running head: GROUPS AND CONFORMITY References Aronson, E., Wilson, T. D., & Akert, R. M. (2007). Social psychology. (6 ed.). Pearson. Retrieved from http://wps.prenhall.com/hss_aronson_socpsych_6/64/16428/4205769.cw/content/index.ht ml Campbell, J. D., & Fairey, P. J. (1989). Informational and normative routes to conformity: the effect of faction size as a function of norm extremity and attention to the stimulus. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(3), 457-468. Gerard, H.B., Wilhelmy, R.A., & Conolley, E.S. (1968) Conformity and group size. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 8 (1), 79-82 Griskevicius, V., Goldstein, N. J., Mortensen, C. R., Cialdini, R. B., & Kenrick, D. T. (2006). Going along versus going alone: When fundamental motives facilitate strategic (non)conformity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91(2), 281-294. Kiesler, C.A. (1963) Attraction to the group and conformity to group norms. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,31(4), 559-569 Latane, B., & Wolf, S. (1981). The social impact of majorities and minorities. Psychological Review, 88(5), 438-453. Mann, Leon. 1986. “Social Influence Perspective on Crowd Behavior.” International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters 4:171-192. Milgram, S., Bickman, L., & Berkowitz, L. (1969). Note on the drawing power of crowds of drawing power of crowds of different size. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 13(2), 79-82. Ross, L., Bierbrauer, G., & Hoffman, S. (1976) The role of attribution processes in conformity and dissent: Revisiting the asch situation American Psychologist, 148-157