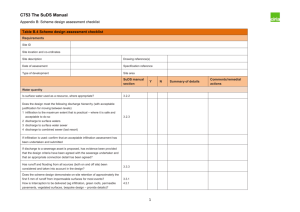

Crichton 2005

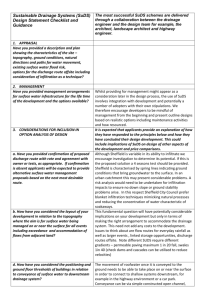

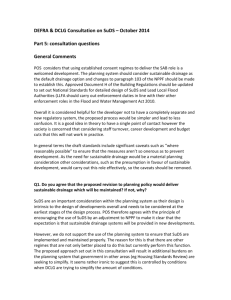

advertisement