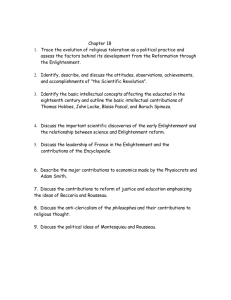

The Age of the Enlightenment

advertisement

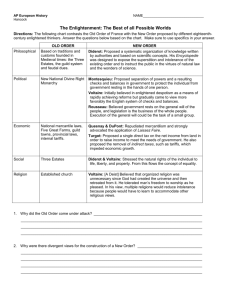

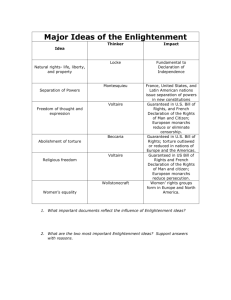

1 The Age of the Enlightenment By Gerhard Rempel We can call the eighteenth century the age of the enlightenment because it was both a culmination and a new beginning. Fresh currents of thought were wearing down institutionalized traditions. New ideas and new approaches to old institutions were setting the stage for great revolutions to come. I. Social Milieu 1. autonomy of reason 2. perfectibility and progress 3. confidence in the ability to discover causality 4. principles governing nature, man and society 5. assault on authority 6. cosmopolitan solidarity of enlightened intellectuals 7. disgust with nationalism. These enlightened philosophes made extravagant claims, but there was more to them than merely negations and disinfectants. It was primarily a French movement because French culture dominated Europe and because their ideas were expressed in the environment of the Parisian salon. Therefore, it was basically a middle-class movement. They, nevertheless labored for man in general, for humanity. Clearly the feudal edifice was crumbling, but there was no real antagonism between the bourgeoisie and the aristocracy as yet. One can detect the bourgeoisie struggling for freedom from state regulations and for liberty of commercial activity. It is also evident that a wave of prosperity brought a greater degree of self-confidence to the bourgeoisie. Great fortunes were made every town. Mercantilism was loosening its hold on the economy. By 1750 the reading public came into existence because of increasing literacy. Yet the philosophes lived a precarious life. They never knew whether they would be imprisoned or courted. Yet they assumed the air of an army on the march. 2 II. Intellectual Setting From the 17th century the philosophes inherited the rationalism of Descartes. but the impulse of natural science alchemized into the Enlightenment. Newton had discovered a fundamental cosmic law which was susceptible to mathematical proof and applicable to the minutest object as well as to the universe as a whole. Maupertuis and Voltaire made Newton common property by 1750. John Locke had denied innate ideas and derived all knowledge, opinions and behavior from sense experience. Condillac carried this to its conclusion by insisting that even perception was transformed sensation. So the traditional anthropocentric view of the universe lay in ruins and with it the anthropomorphic conception of God. Hence Montesquieu, Voltaire, the encyclopedists and physiocrats created the synthesis of social science which was based on past progress. All of this was done in an atmosphere of religious, political and economic controversy. Biblical criticism came from Hugo Grotius. Political economists, shocked by the difference between prosperous Holland and backward Spain, first posited precious metals as the source of wealth, then commerce, and then agricultural production (as developed by the physiocrats). In all this controversy, social science was beginning to yield evidence--the critical and historical method of Pierre Bayle. Exotic travel literature had its effect as well. It supported the positivist, experimental mentality of the 18th century. It brought the aura of the "noble savage" into prominence. There was a moral sense in natural man. Rousseau and the encyclopedists succumbed to this idea. But that was not the case with Montesquieu and Voltaire. By 1750 the social sciences had already become inductive, historical, anthropological, comparative, and critical. III. Method There was great faith in the instrument of reason rather than mere accumulation of knowledge. Doctrinal substance was not as important as overall philosophy. We need to keep this in mind if we want to understand the Enlightenment. It was not so much Descartes "reason" but rather Newton's laws--not abstraction and definition, but observation and experience were points of departure. What placed the stamp on the Enlightenment was this analytical method of Newtonian physics applied to the entire field of thought and knowledge. Order and regularity came from the 3 analysis of observed facts. Lessing said that the real power of reason lay not in the possession but in the acquisition of truth. So pure analysis was applied to psychological and social processes. From here on out the doctrine of historical and sociological determinism (the application of the principle of causality to social science) was generally accepted. Many historicists have ridiculed this naive scientific positivism. By facile dogmatism the philosophes frequently ignored their own method. Their new ideal of knowledge was simply a further development of 17th century logic and science. But there was a new emphasis on 1. the particular rather than the general 2. observable facts rather than principles 3. experience rather than rational speculation. Except for David Hume's skepticism, the philosophes' faith in reason remained unshaken. IV. Enlightenment and Religion It was an age of reason based on faith, not an age of faith based on reason. The enlightenment spiritualized the principle of religious authority, humanized theological systems, and emancipated individuals from physical coercion. It was the Enlightenment, not the Reformation or the Renaissance that dislodged the ecclesiastical establishment from central control of cultural and intellectual life. by emancipating science from the trammels of theological tradition the Enlightenment rendered possible the autonomous evolution of modern culture. Diderot said, if you forbid me to speak on religion and government, I have nothing to say. Hence natural science occupied the front of the stage. Most of the philosophes wrote on natural science. To Diderot, d'Holbach and the encyclopedists all religious dogma was absurd and obscure. LeMettrie and d'Holbach were consistent determinists. Voltaire disagreed with them and said they had a dogmatism of their own. Diderot too insisted on the free play of reason. But he was an unashamed pagan and believed in a kind of pantheism or pan-psychism, not pure atheism or materialism. He was humanistic, secular, modern and scientific. He expected from his method a regeneration of mankind. 4 English deism, however, was more pervasive in the Enlightenment. It emphasized an impersonal deity, natural religion and the common morality of all human beings. Deism was a logical outgrowth of scientific inquiry, rational faith in humanity, and the study of comparative religion. All religions could be reduced to worship God and a commonsense moral code. There was a universal natural religion. Yet, it was David Hume, the Englishman, who cut the ground from under his deist friends (Natural History of Religion). Natural religion rested on the basic assumption that man is guided by the dictates of reason. Mind is the scene of the uniform play of motive. The motives of man are quantitatively and qualitatively the same at all times and in all places. An empirical study of the nature of man, said Hume, reveals not an identical set of motives but a confusion of impulses, not an orderly cosmos but chaos. The elemental passion, hopes and fears is the root of religious experience. Religions may be socially convenient but being rooted in sentiment they lack the validity of scientific generalization. A rational religion is a contradiction in terms. Hume here comes close to demolishing the entire rationalist philosophy of the Enlightenment--its natural rights, its self-evident truths and its universal and immutable laws of morality. Voltaire is in the middle between the materialism of the Encyclopedists and the skepticism of Hume. His ruthless and comic deflation of theological sophism prevented him from recognizing the deepest drives of Catholicism. He conveyed the power of intellect to his generation, but also saw the limitations of reason. Reason was, after all, a poor instrument, but it was the only weapon that raised man above the animals. He believed in the argument from design or "first cause." But this no longer sufficed Diderot and Hume. Voltaire accepted the classical ideal of the brotherhood of man and the universal morality of man. He was essentially a humanist--the greatest humanist of the Enlightenment. He had not the depth of David Hume or Immanuel Kant, but they could not have done his work. Voltaire had only one absolute value: the human race. The central theme of the Enlightenment is the effort to humanize religion. All philosophes rejected original sin. Here Pascal became a problem for them. For Pascal used their method of analytic logic to prove the existence of original sin and the utter inability of the unaided human reason o solve the problem without accepting the authority of faith. How do you explain the "double nature" of mankind? It becomes intelligible only through the doctrine of the fall of man. Pascal haunted Voltaire all his life. The cruel laughter of the Candide could not suppress the problem of evil. In the upshot he accepted Pascal's analysis of human nature. By becoming an 5 agnostic he became prisoner of Pascal's argument--reason without faith ends in skepticism. Rousseau had a more original solution to Pascal's problem. In his two discourses he painted a picture of depravity of society that would have delighted Pascal. If he accepted degeneration how was he to explain radical evil? He discovered a new agent of degeneration--the "fall of man"--not god or individual man but society. Thus salvation comes through the social contract. Man must save himself. In social justice is the meaning of life. It was neither a theological or metaphysical solution but a modern solution. V. History The Enlightenment rescued history from the antiquarians and the philologists: Voltaire, Hume, and Gibbon. Pierre Bayle was the real founder of historical criticism and the intellectual father of the historians of the Enlightenment (Historical and Critical Dictionary, 1697). To get at the reliable and incontrovertible facts of history was for him not a point of departure, but an end in itself. His Dictionary was a record of errors and historical falsehoods. He transformed the dictum that history was nothing more than a record of crimes and misfortunes of mankind. He did for history what Galileo did for science. Historical truth could only come from the objective examination of the human record. The Enlightenment ideas made meaning out of this record. Empirical causation and human solidarity, despite incessant warfare, and the idea of progress made a conceptual mastery of the chaotic and meaningless facts of history. Enlightenment historians applied the whole culture of their age to the past. Not the "unique event" of Leopold von Ranke, but the evolution of generic man--the spirit of the times and nations--are the essence of history. At the base of Voltaire's conception of civilization lay the great monarchies of Europe with their institutions, their quests for power, but also their promotion of economic welfare, the basis of cultural progress. Voltaire believed in the republic of scholars and in the primacy of ideas in historical evolution. Ideas were the motive force. Thus he became the prophet of progress (Century of Louis XIV and his more important Essay). But how does one reconcile progress and the universality of human nature? Human nature reveals itself only in historical evolution. Progress is the gradual assertion of reason. To some degree, this was didactic history. 6 Hume also accepted the uniformity of man and failed to grasp the irrational factors in human history. But he too asserted the primacy of ideology. Yet this static view began to change. He believed neither in reason or in progress and was profoundly occupied with the historical process--that is with change as such. He put facts above theory and the unique aspects were more significant than the common occurrence (History of England). Hume, of course, was horrorstruck with Voltaire's sweeping generalizations. VI. Social Science and Political Thought The philosophes did not discover natural rights theory, but they made it the foundation of the ethical and social gospel. They introduced natural rights into practical politics. They gave natural rights the dynamic force which revealed its explosive energy in the French Revolution. But their argument moved steadily away from metaphysics toward empiricism--away from reason toward experience. Liberty of the person, security of property and freedom of discussion were less rooted in abstract reason than in commonsense views of fundamental human needs, impulses and inclinations. In spite of the utopianism of Rousseau, the rest had a sense of reality. Reason is still primary, but it is not insurrectionary or bloodthirsty. Only in society could man realize his full potential. They believed in the social function of knowledge. Except for Rousseau, none of the philosophes agitated for a radical transformation of society. All of them, like Voltaire, defended enlightened absolutism. Montesquieu published his Spirit of the Laws in 1748. He expressed here real hatred of despotism, clericalism and slavery. Being a member of the petit noblesse, he called for an "intermediary corps" and fundamental laws to temper the monarchy. His former colleague magistrates called it restitution of the ancient constitution. So, he influenced both the aristocratic reactionaries who wanted to revitalize feudal estates and parliaments, and the honest liberals who idealized English constitutionalism with its principle of separation of powers, the basis of modern constitution-making. This book was the first study in ideal sociological patterns. He advocated the examination of a variety of constitutional forms to discover the republic and its inner law. A network of interacting forces, if altered, affect the equilibrium of the whole structure. He is the founder of the typology of constitutional patterns. 7 The Encyclopedists had a more dynamic conception. But they also believed in metaphysical norms to which societies must conform. Hence natural religion, natural morality, natural rights, and natural economies should prevail. They also popularized the idea of progress, stated more clearly later by Turgot and Condorcet. They used the Leibnitz idea of continuity. The Physiocrats shared with the philosophes a rationalist, hedonist and utilitarian outlook. Natural rights were thought to be necessary for economic progress. They were opposed to the rivalry and jealousies of mercantilism. They reduced all social science to economics. Quesnay started with an examination of the agricultural situation in France. He wanted protection for agriculture and promoted the Third Estate. But agriculture came first and liberalism second. He thought there should be harmony between positive laws and natural laws and that this harmony could be established via reason. The sovereign was to be a "legal despot." This vague utopian constitutionalism was a regressive step from the ideas of Montesquieu. Rousseau rejected all compromise with contemporary society. He called for a moral reformation, a revival of religion, and a purification of manners. He passionately asserted the moral and legal equality of man, the sovereignty of the people and the authority of the general will. He wanted a return to primitive simplicity. While he realized that his "state of nature" never existed, he asserted that self-knowledge was the source of his proofs. In two discourses he exposed his unlimited personal individualism. Yet in the social contract we get the glorification of unlimited absolutism of the state. Freedom for Rousseau is the submission to the law which the individual has imposed on himself. It is a voluntary consent to a necessary law. By entering this state, men gain the enlargement of their perceptions and capacities. Political and intellectual freedom is worthless for man, if he does not have moral freedom. The function of the state is to bring legal and moral equality about. Physical, intellectual and economic equality are beyond human remedy. The state, according to Rousseau can interfere with property only if legal and moral equality is jeopardized. In his book Emile he explains that the young must learn the compulsion of things but be protected from the tyranny of men. All must obey the general will as a law of nature, not as an alien command but because of necessity. This is only possible if society makes the laws which it obeys. Hence a radical political and social revolution is necessary. He demanded man's mastery over nature and projected a moral rationalism.