I was born in Mount Pleasant, Iowa, on August 12, 1892

advertisement

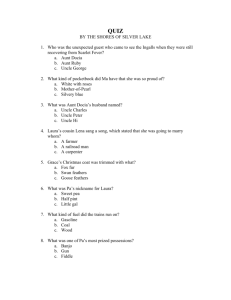

The Early Life of Florence McClure Harlan Means As dictated to her daughter-in-law Lillian Kolsrud Harlan Hand published by her granddaughter Anne Harlan New York 2003 Orphanage Children with Matron and Assistant Outside headquarters of the Pentecostal Church Indianapolis, Indiana Clarence McClure - center 3rd row Elmer - at his left Florence - below and to Elmer's left (2nd row, not white dress) George - at her left Marvin - seated in front of Florence (in light shirt) 2 I was born in Mount Pleasant, Iowa, on August 12, 1892. My father was Charles Arthur McClure; my mother was Margaret Marshall McClure. Elmer Earl McClure was about fifteen months old at the time. Clarence and Clara were also born in Iowa. Four or five years later we moved to Missouri for two years. While living there Clara died of “summer complaint”, and George and Marvin were born. Clara was buried in Harmony Cemetery about five or six miles from Edina, Missouri. Father farmed some land owned by Uncle George A. McClure, his oldest brother, who was eighteen years older than Papa, who was the youngest of eleven children. Mother was next to the youngest of ten children. Mother became ill with tuberculosis so the family moved back to Iowa. From there they had hoped to find some way to get to Denver to prolong her life, but the disease was too far advanced to make that effort. Mother died in January, 1901. We were living with Grandpa McClure. His eyesight was failing, and he died in September of the same year. Grandpa’s farm was north of Mount Pleasant, near Swedesburg, Iowa. Uncle George lived there, and also Orlie Miller, the son of Papa’s sister Julie. Orlie was raised by my grandparents. He had a speech impediment but was a 3 hard worker, and “worked out” for one dollar a day at times. Papa got a job for the railroad laying track and repairing roadbeds. He roomed in Wayland when working on the railroad. For the next year I lived with Emma and Joe Bushart across the road and on the next hill, as she didn’t think it was right for me to be living with all those men and boys. I lived there “a year lacking three weeks”. I had a “ball” when I lived with them; there were many gatherings with the German relatives and children to play with. After they had a child of their own I went to live in Wayland with Grandmother McClure’s sister Julia Jessup, and her fifty-fiveyear-old spinster daughter Viola. Viola’s father, Uncle William Jessup, was blind. I could help guide him up town to visit with his cronies but I wasn’t always dependable about being on hand to bring him home. Wayland was somewhat a retirement town for farmers. I went there in midwinter and went to school there—my only time in a “town” school. I remember walking the railroad track with brother George and Papa to go to Olds, and then got to Mount Pleasant somehow. There we stayed in a home owned by Aunt Samantha and Uncle Peter Roth. She was an older sister of Papa’s. Elmer was staying with Uncle Jim Marshall, mother’s youngest brother , and his wife Aunt Adaline, as Elmer could help them with their dairy at Winfield. Clarence was at Aunt Samantha’s at their farm. George and I got small pox, probably from germs left from Aunt Samantha’s boys when they had it. The closet may not have been fumigated. 4 Papa had heard about an orphanage in Indianapolis that was just starting, with only four boys. This was run by the Pentecostal Bands of the World. Some missionaries from there were in the area and Papa was going to send me with them to Indianapolis, but when we got small pox I couldn’t go. When I got out of my quarantine Papa took me to their headquarters in Mount Pleasant, and a lady, Clara Moore, took me on the train to Indianapolis. We stayed several days in the Indianapolis headquarters. The sleeping quarters were on one side, the chapel on the other, and in the basement, printing presses for their newspaper, “Light of the World.” T. H. Nelson and his wife had charge of the place. I was taken to the orphan’s home which was on the outskirts of Indianapolis, at the east end of the Washington Street car line. There were four boys there; two were nephews of the Nelsons, Ellis and Donald. It was a ten-acre tract of land with houses. One building had been a barn, and that was made into a school house. The house near there was the boys’ cottage. I lived with the lady who was the housekeeper and cook. She was very nice, and her name was Auntie Taylor. I arrived at the orphanage when I was ten years old, in August 1902. Auntie Taylor would teach me Bible verses while she did her cooking. Sometime that year Papa brought my brother George as he had to be in school and Papa couldn’t care for him. When Uncle Peter Roth was ill and Aunt Samantha was busy caring for him she couldn’t take care of Clarence. So Papa, who was working in a glass factory in Chicago then, went to Iowa for Clarence and brought him to the orphanage. Marvin had been living with mother’s sister 5 Aunt Mat and her husband, Frank Cox; and when she died Papa had to bring Marvin to the orphanage. Later Papa brought Elmer so we at least were all together. This had been Mama’s wish. The entire orphanage moved to Plainfield, Indiana, west of Indianapolis, where there was land for the older boys to help raise crops. As the orphanage grew and there were more girls I was moved to the girls’ cottage. When I got there the teacher, Mrs. Dunbar, said anyone was vain to wear ruffles or lace on their clothes and made me cut the lace off the dresses Viola and Aunt Julie made for me before I left Iowa. Mrs. Dunbar had two children who were, of course, her favorites. I was in the orphanage a total of five and a half years before my Uncle George came from Mississippi where he and Orlie and my father had a plantation four and a half miles east of Canton, Mississippi. I was happy to leave the orphanage. Uncle George took us by Interurban car into Indianapolis and we stopped at a department store where he bought one of the boys a much needed pair of shoes, and a red hat for me to protect me from the Mississippi sun. Uncle George put what he could in his suitcase, and each of us carried our bundle of belongings. The train trip took most of three days so we were pretty tired. Papa and Orlie met us with a carriage, two horses, and a mule. I was happy to see Papa. There were many Negroes in the town, and everyone gawked at us. It was a nice house: three rooms upstairs and three rooms downstairs, and I had a room all to myself. My work assignments at the orphanage helped 6 prepare me for the work ahead of me cooking and caring for the seven boys and men. We arrived there in January, and we had much rain that month. Mud was deep and rolled up on the wheels. Then the work began in the fields. Papa worked with the county agent on experimental farming—feed for cattle and hogs, as well as cotton and beans, a new crop for that part of the country. I was cooking, washing, and ironing (with irons heated on the stove). However, Uncle George had been a bachelor for so long he always made the breakfast, alternating between pancakes with sugar syrup and biscuits with gravy. The boys helped set out five acres of peach trees. We ordered some young turkeys but stray dogs would get after them. There was swamp area on the south end of the property, so they cleared that somewhat of brush and we then had a fine hay meadow. I baked six or eight loves of bread twice a week. Sometimes we would have corn bread or mush. I canned peaches, tomatoes, jelly from wild grapes and plums in half-gallon jars. Uncle George worked in the garden and not in the field. Clothing was a problem for me as Papa didn’t have money and I had to go to Uncle George if I needed something. He would get out the catalog and figure how much things were and then go to town. I was most embarrassed to have to tell him I needed underpants. Then, due to the diet, I was chubby and wanted a corset. I sold the hat Papa bought me for Easter so I could get one dollar to buy a corset. I also managed to get some dress material and a friend made me a pretty dress. When I came down to go to the “Snowdiggers” (northern white folks) picnic all dressed 7 up Uncle George wanted to know where I got that dress. They couldn’t afford to have me dressing like that. I realized there was absolutely no future for me there just keeping house for the boys and men, so when Lulu Harlan came to visit her sister Mary Chisman, I decided I wanted to go back to Iowa with her. Mary Chisman and her two daughters, Joy and Glee, who were pre-school age, were going back to Iowa too to visit Mary Chisman’s mother, Aunt Cynthia Harlan, and sister Grace, who taught piano at the conservatory in Ottumwa. ( Joy and Glee used to come and visit me, and Mary Chisman would phone to tell me to watch for them, as the old tom turkey would get after them.) Papa and Uncle George were not in favor of my going back to Iowa as they felt I would starve up there. What would I do? I wasn’t able to attend school in Mississippi and do my work too. I insisted on getting somewhere so I could get an education and have some kind of a future. Uncle George couldn’t understand my wanting to “go out in the world” and I would probably come back on my hands and knees and I wouldn’t be welcome. Papa bought my ticket and when we left he gave Mary Chisman ten dollars for anything I needed. I wanted to bring my share of lunch to eat on the train, so I fried chicken and packed it in a tin can and put the cover on to keep it warm. It was around the first of July and very hot on the train. When Mary Chisman found what I had in the can she said it wouldn’t be safe to eat so she threw it out the window, whereupon I started to cry and cried most of the way to Iowa. I couldn’t stand 8 the thought of that wasted food when my brothers could have enjoyed it; and I was then unable to contribute my share for the trip. I was lacking two months from being eighteen at this time. On arriving in Ottumwa we went to the Harlan home where Grace, Lulu, and their mother Aunt Cynthia, lived on Ward Street. I got in touch with Ed Roth, my cousin, as Papa had asked me to do that. They had me come to their home but there wasn’t much to do there. He and his wife Ella were on the hospital board and one day she said that if I was older I could go into nurse’s training. I decided I would very much like that, so Ed decided he would try to get me in by bluffing about my age. The Superintendent of the hospital was undecided about me but finally told me that I could try my two-month probation period and see how I would do. I was the thirteenth nurse in the class. Our rooms were on the third floor of the west wing. We had our classes and lectures in the evening when off duty. I was a pretty “green” girl from the country and had some adjusting to do to get accustomed to running water, electricity, and all those conveniences. We had an hour off a day to study or whatever we wanted to do, and four hours off on Sunday. Some of our duties would be to accompany doctors on rounds, scrub all bed pans in the bathtub each morning, make and change beds, and air mattresses on the porch each time a patient would leave. After a death or contagious disease the room and everything in it had to be fumigated. We would light a 9 sulfur candle to fumigate and would quickly stuff rags all around the door to keep it from invading the hall. We would bring trays to the patients. The hot food had been sent up from the kitchen by dumb waiter to the diet kitchen where there was a two-burner gas plate. There we would fill the trays. After the two-month probation period, if we passed, we got our uniform and cap. After two years a band was put around the cap. The training period lasted three years. This was a 35-bed hospital, though seldom full. Miss Trotter, the superintendent, ran the place with the help of student nurses. After graduation we took private cases, in or out of the hospital. My first private case was in the hospital—an appendectomy; my second case was in a private home for an elderly lady with a broken hip. Next was one of the owners of the Iowa Café, a heavy man with a hernia. I was kept busy on cases with little rest in between. I was living a couple of blocks from the hospital with Chief of Police, Officer Joe Beeman, and his wife Clara. A few other nurses roomed there also. They had a parrot who always greeted Mr. Beeman with “Hello Joe.” Mrs. Beeman was a seamstress. She later made my wedding dress. There was not much social life in those three years: long hours, classes, lectures, studying, and in your room by 10 PM. Grace and Lulu often had parties, and they always asked me to attend if I wasn’t working. At their place I met their cousin Orville (“O. D.”) and his younger brother George. Aunt Cynthia’s house was a good place for parties. We also had sleigh rides in winter 10 and oyster stew at the house. Aunt Cynthia would have to water down the stew sometimes as more and more young people would show up. “We knew you wouldn’t mind,” they would say. One Easter when attending the Davis Street Christian Church, O. D. asked if I would like to walk home. Half way across the bridge it poured rain, and my Easter hat blew into a puddle. O. D. and George had a horse, but this had been George’s night for the horse and buggy. We dated some at young people’s activities, like festivals; or he would come to the hospital and we would visit in the reception room, or go for walks or occasionally to a movie. My nurse’s training was completed in spring of 1913, after which I would accept nursing jobs in homes. One job was for an old couple down on a farm outside Centerville. While I was taking care of the lady the man had a runaway accident, so I had to care for him too. They wanted to adopt me. I was anxious to get back to Ottumwa, so they asked if I had a boy friend up there. Then they invited O. D. down for a weekend. A beautiful night in the swing under the trees brought on a proposal of marriage. While still caring for the old couple I was going out to the pump for cold water one night when I got my feet tangled in a rope the granddaughters had left from the screen door. I fell still holding and protecting the two lovely cut glass tumblers, but breaking my arm—a green fracture. They wanted to send for a doctor or nurse, or send me to Iowa City, but I insisted on leaving by train the next day for Ottumwa. There my arm was set, and I was unable to work while it 11 healed. While waiting for the arm to heal I went out to Winfield to visit some of my mother’s relatives: my grandmother Marshall, who was bedridden, and my two aunts who took turns caring for her in their homes, Aunt Belle Olinger and Aunt Hattie Hatton. On January 12, 1914, O. D. and I were married. He was working in Albia and wanted me to come up there. My landlady Mrs. Beeman had made me a lovely off-white wedding dress and tried to convince me to get married in Ottumwa. But I took the dress and took the train to Albia. O. D. had discouraged my having my brothers come up as we wouldn’t be having any family at the wedding. Yet when I got off the train I found his father and brother George were there. We went to the Mayor’s home where we were to be married. The Mayor’s wife was out, and I stalled, hoping she would get back so there would be another woman present. I finally came out of the bedroom not wearing the wedding gown. Next thing I knew the ceremony began. Where I had been in tears upstairs I found myself laughing, somewhat hysterically I suppose. When we went out to dinner—the three Harlan men, O. D.’s boss, and myself—I sat there not eating while the others had a big dinner. The restaurant was in a depot hotel where we stayed and the next day left by train on our honeymoon. We stopped off in Council Bluffs two days with O. D.’s aunt, his father’s sister, then on to Beatrice, Nebraska, where we stayed with O. D.’s Aunt Jane Ralston, whose husband Perry was a tailor. We also visited her daughter and family in the country. Nebraska was miserably cold while we were there. 12 We went back to Russell, Iowa where O. D. and George had been rooming. Mrs. Cobb (“Auntie Cobb”) ran the rooming house for railroad men and construction men. The depot agent always lived there. They had one daughter Marie, who later married George Harlan. They also raised twin girls, Catherine and Elizabeth, from the time they were about five months old and their mother died. Their father was a neighbor of Mrs. Cobb and didn’t know how he could manage them. When we arrived the girls were about four years old, all prettied up and sitting on the steps waiting to see the bride. While O. D. continued working on a school house in Albia I went back to Ottumwa and stayed at the Harlan home with O. D.’s father in the house on Chester Avenue that O. D. and George built after their mother died. Their mother had died the previous year the week before Easter Sunday. She had been taken to Chicago for surgery but had cancer and died three days later. Grandma Brooks, O. D.’s mother’s mother, lived in the house next door to their former home on Ransom Street. I remember how she would shampoo her hair with rain water, and she had a homemade tonic she would comb through her hair. Her name was Mathilda, and her daughter, O. D.’s mother, was named Quintilla. Grandma Brooks was about 81 when she died. She died in 1915 when Wayne was a baby. The house on Chester Street was a nice brick home, but for the first year or so it had no connection with sewers, so there was no indoor plumbing. When I got pregnant I was sick much of the time. I couldn’t stand the smell of O. D.’s 13 father’s pipe. Also, he would sleep late, and I didn’t enjoy having to cook late breakfast for him. George Harlan roomed upstairs but didn’t take meals with us. When I became pregnant I made diapers and baby things from outing flannel. O.D.’s aunt came to visit for a week from Council Bluffs. In the spring we went to Batavia, two towns east of Ottumwa, where O. D. and Frank Wheaton were building a school house. We lived in a bunk house alongside a stream. We stayed there all summer. I could walk down the railroad track and find wild patches of gooseberries, elderberries, and plums. I went back to Ottumwa to stay with the Brumleys, because she had had a number of miscarriages, and the doctor said she was to stay off her feet until the eighth month to enable to have the one she was carrying at the time. I would help them during the week and then go back to the Chester Street house on weekends when O. D. would come home. When he finished the work in Batavia he came home to the Chester Street, house, so I went back to the house too. Mrs. Brumley had her baby boy Vernon two weeks before I had my baby. Wayne was born on December 8, 1914, about 8:30 AM, with Aunt Till as midwife, as she was for my other three children. Dr. H. W. Vincent delivered the baby. Wayne Richard weighed 8 ½ pounds, and he was a very good baby. 14