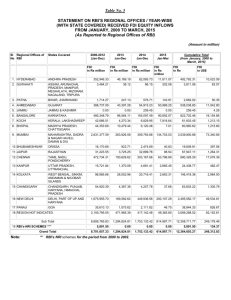

foreign direct investment (fdi) regime in the

advertisement