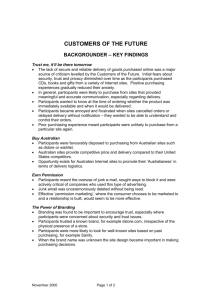

Chinese customers in British and Japanese multinational retail stores

advertisement