IN THE HIGH COURT OF MALAYA AT JOHOR BAHRU IN THE

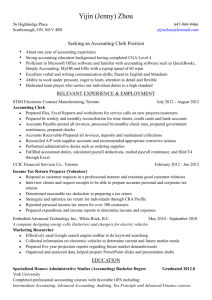

advertisement

IN THE HIGH COURT OF MALAYA AT JOHOR BAHRU IN THE STATE OF JOHOR DARUL TA’ZIM CIVIL SUIT NO: 22-40-2009 _______________________________________________________ BETWEEN SENG YONG ENGINEERING CONSTRUCTION WORKS SDN BHD (Company No. 729178-H) … Plaintiff AND ECOMETRO (M) SDN BHD (Company No. 287080-P) … Defendant JUDGMENT GUNALAN A/L MUNIANDY, J.C: Background of Plaintiff’s Claim [1] The plaintiff (‘P’) was engaged by the Defendant (‘D’) the main contractor, as sub-contractor for the project known as ‘Design Construction and Commissioning of a New Railway Bridge at No. 1766, 1767 and 1768 at KM 724.41 and associated works near Kulai Railway Station’ (the said project). In November 2006, the Defendant pursuant to an oral agreement with the Plaintiff, nominated the Plaintiff as one of the sub-contractors to supply construction materials and provide labour for the construction of a new bridge for the said project at the contract sum of RM1,182,590.00. Pursuant to the oral agreement and the said nomination, Plaintiff had supplied all construction materials and provided labour and carried out the said works with its own labour and equipment and completed all the works on or about September 2007. The Defendant after having paid a sum of RM774,000.00 to the Plaintiff had defaulted payment of the balance contract sum of RM408,590.00 despite repeated demands for payment by the plaintiff. Therefore, the plaintiff claims damages or a sum of RM408,590.00 by way of damages together with interests and costs. Defence Case [2] The total contract value had been agreed upon between the parties at RM970,000.00 despite the absence of a formal written agreement. The agreed price is inclusive of equipment, materials, labour charges. Hence, P was not entitled to make separate claims for labour charges. P had wrongfully submitted invoices in excess of the contract price without D’s consent. Upon deducting the sum already paid to P, the balance owing was only RM196,000.00. [3] P was said to have failed to provide certain machinery and equipment that it was supposed to provide, compelling D to rent these from third parties. The costs (rentals) incurred were borne by D. Therefore, D was entitled to set-off a sum of RM300,000.00 from P’s claim. As a result, P was liable to pay D a sum of RM104,000.00 for which D has counterclaimed. [4] P was alleged to have contributed to delay in completion of the project for which D is entitled to liquidated damages as pleaded. [5] Further, that D was negligent in carrying out its scope of work causing damage to the railway cable and liability for losses due to derailment of train coaches. D also counter-claimed for general and other damages flowing from losses suffered due to loss of reputation, cash flow problems and numerous inconveniences alleged to have been caused by P’s carelessness and negligence in discharging their obligations. 2 Summary of Issues To Be Tried [6] 1) What was the scope of works and the value of the subcontract agreed to by both parties, whether it was RM1,182,590.00 as claimed by P or RM970,000.00 as claimed by D? 2) Whether D is liable to settle all the invoices received from P? 3) Whether D was estopped from disputing the invoices totalling RM774,000.00 that D had fully settled? 4) Whether P had a right to claim for equipment, materials and labour? 5) Whether the amount owing by D to P was RM408,590.00 or RM196,000.00? 6) Whether D was entitled to set-off against P’s claim the costs that D had incurred in providing crane services? 7) Whether D was entitled to counter-claim against D for carelessness, negligence, etc. throughout the construction work? 8) Whether P was careless, negligent, etc. and if so, whether D could claim damages for LAD imposed on D and other losses that D had incurrent as set out in the particulars of the counter-claim? Analysis of Evidence and Findings on Issues Value of the Sub-Contract [7] As there was no formal written sub-contract (‘S/C’) in existence, the terms and conditions (‘T & C’) of the sub-contract were to be determined from the available documents: quotation by P, purchase order (‘P.O’) issued by D and the invoices issued by P to D. The contract awarded to P consisted of 3 packages : new railway bridges at No. ‘1766’, ‘1767’ and ‘1768’. The dispute revolved around the total sub-contract price, 3 which P contended was RM1,182,590.00 while D contended it was RM1,045,00 only the difference being RM137,590.00. [8] D disputed the S/C price computed by P as per PW1’s evidence based on the invoices on the ground that several invoices were invalid for two reasons: the invoices went over and beyond the agreed price and certain works carried out by P for which there was neither request nor variation order issued by D. For ease of reference the disputed invoices were Exhibits P1, P5, P6A –B, P7A –B, P11A – B, P12A – B and P13A – B. [9] Exhibits P1 and P5 relate to Bridge No. 1766 and were challenged for being “double or overlapping claims” for the same works under another invoice, Invoice No. “00114” [Exhibit P16 ]. With regard to the allegation that Exhibits P1 and P16 were overlapping claims, it can be clearly seen that these were separate and specific invoices at different points in time. Works were carried out under both Invoices P1 and P5 long before P16 was issued. The lapse of time between P1 and P16 was almost 7 months while that between P5 and P16 was about 1½ months. I agree with plaintiff’s counsel (‘P/C’) that a comparison between P16 and the other earlier invoices would show that it defies logic to claim that the scope of works stated in P16 overlapped with that in the earlier invoices. There was no similarity from the perspective of price and nature of works. More importantly, when P16 was issued and received by D, no objection was raised as to its correctness and validity. In any event, the onus was on D to prove the allegation of double-claim but D had failed to adduce any evidence to discharge this onus. Merely making an allegation and without strictly proving it fell short of satisfying the onus of proof borne by D. Similarly, merely by adding the word ‘Temporary’ to Exhibit P5 and the P.O. [Exhibit P4] when the word was not found in the document did not amount to the required proof. [10] The other 5 invoices disputed by D concern ‘Bridges 1767 and 1768’ and the reasons for the dispute are: 1) There was no purchase order for these bridges. Instead the S/C price was dependent on Invoices No. ‘00049’ and 4 ‘00102’ which came to a total sum of RM360,000.00 and any further invoice constitutes double claim; 2) Scope of works for both the bridges did not differ much but for ‘1767’ the claim is only RM51,000.00 whereas for ‘1768’ it is RM421,530.00 As regards reason (1) above, nowhere in P’s case was it contended that there was a P.O. for these bridges. It was common ground that the S/C price depended on invoices only as compared to ‘1766’ for which it depended on a P.O. and a quotation, apart from invoices. For the former, D never, in the course of dealings with P, objected to any payment based on invoices. Neither did it insist on any P.O. before payment could be made. As pointed out by P/C, D seemed to be inconsistent in its defence. [11] Coming to reason (2) above, DW1 testified that there was a huge difference in price for bridges ‘1767’ and ‘1768’ although the layout plan and drawings reveal only minor differences. While D/C stressed this point, P/C drew attention to the testimony of DW1 on the same aspect under cross-examination where he affirmed that for ‘1767’ P only supplied girder (beams) to support the temporary steel bridge No. ‘1767’ whereas for ‘1768’ P fabricated and installed 2 sets of temporary bridges which D purchased from the Malayan Railways (‘KTM’). Therefore, the allegation of the huge monetary difference being unjustified was plainly misconceived. Invoices Not Disputed [12] In reply to the defence allegation of ‘double/overlapping’ claim, P/C laid emphasis on the fact that all the invoices were contemporary documents which were never challenged or objected to by D ever since the date of receipt until the sub-contract works were completed by P. This fact was borne out by the evidence. The question arose whether D could raise the challenge at this point when it had not done so at the time of receipt and when a demand for payment had been made? Either way, doubts arose as to the credibility of the challenge. My attention was drawn to the Court of Appeal case of Boonsom Boonyanit v. Adorna Properties Sdn. Bhd. [1997] 3 CLJ concerning the principle relating to judicial appreciation 5 of evidence where the credibility of oral evidence had to be tested against contemporaneous documents. In that case, Gopal Sri Ram, JCA (as he then was) said at p. 317: “Judicial appreciation is concerned with the process of evaluating the evidence for the purpose of discovering where the truth lies in a particular case. It includes, but is not limited to, identifying the nature and quality of the evidence, assigning such weight to it as the trier of facts deems appropriate, testing the credibility of oral evidence against contemporaneous documents as well as the probabilities of the case and assessing the demeanour of witnesses.”. [13] In applying the principle as elucidated above, having regard to the contemporaneous documents in the form of invoices duly issued and acknowledged without any objection being raised thereafter, I found the defence contention of ‘double claim’ to be obviously unsustainable. The same applied to the contention that the items of claim under Invoice 114 [ P16 ] should be inclusive of those works claimed under 053 and 100 [ P1 & P5] as nowhere in these invoices is it said so. It amounted to no more than an attempt to vary or contradict the contents of a written document when no objection had been made at the earliest possible opportunity or even within a reasonable time frame. [14] On the defence attempt to controvert or vary written documents in the form of the P.O. and the invoices, which D admitted as constituting the S/C price, my attention was drawn to sections 91 and 92, Evidence Act, 1950 which prohibit such variation or contradiction. Reference was made to a case in point, Tractors (M) Bhd. v Kumpulan Pembinaan (M) Sdn. Bhd. [1979] 1 MLJ 129 (FC) where it was held: “(1) on a proper and correct construction of the agreement between the parties, it was beyond argument that the intention between them was that the property in the vehicle was not to pass to the respondent until full payment had been made. It was therefore a hire-purchase agreement and until full payment had been made the appellant had the right to repossess the vehicle on 6 breach of its terms by the respondent. therefore not wrongful; The repossession was (2) the case was therefore on the undisputed facts and as a matter of the proper construction of the agreement and the application of the proper law, an eminently fit one for proceedings in lieu of demurrer under Order 25 Rules of the Supreme Court.”. The Issue of Estoppel [15] This issue was raised by P in the Reply to Defence on the ground that D did not object to any of the invoices that the latter had admittedly received and paid for partially. It was, thus, pleaded that D was estopped from making the allegations in para 3 of the Defence by reason of these facts: that D had neither objected to or questioned the prices stated in the invoices nor made any allegation of any additional works done without request; that D had made payment towards the S/C price without any protest or question; and that the amounts stated in the invoices are with the prior agreement. Every invoice contains the indorsement “Claims to be made within 7 days after receipt of goods”. On the lack of protest by D to the invoices, P/C made reference to the Court of Appeal case of Boustead Trading [ 1985] Sdn. Bhd. v. Arab-Malaysian Merchant Bank Bhd. [1995] 4 CLJ where the relevant part of the judgment reads: “A reasonable man similarly circumstanced as the respondent would have been entitled to assume, as the respondent did, that the appellant was agreeable to the imposition of the 14 days limit. The respondent was clearly influenced by the conduct of the appellant when it paid Chemitrade for those invoices, and this the respondent would not have done had the appellant protested. The appellant’s attempt to raise this point some seven months later, must be classified as unconscionable and inequitable conduct. It ought not therefore to be permitted to question the validity of the indorsement.”. [16] As D in the instant case did not at any time question the validity of the indorsement on the invoices, D/C submitted that it indicated that the indorsement is part of the original agreement and was valid and binding. 7 He also stressed the fact that D had already paid a substantial sum in part settlement of the S/C price without making any objection to the invoices submitted to it. [17] Going by the decision of the Court of Appeal in the Boustead case above, D’s dispute over certain invoices on the grounds as per para 3 of the Defence should be classified as unconscionable and inequitable conduct in the sense referred to by the Court of Appeal. The doctrine of estoppel would apply to estop D from now contesting the validity and correctness of the invoices in question when it was not done at the appropriate time leading P to believe that the invoices were not being disputed. D/C’s submission that the plea of estoppel should be rejected in this case on the ground that as late as April 2008 P could not arrive at the final price was, in my view, misconceived. This was because estoppel was raised in respect of specific invoices that had never been disputed by D and not in respect of calculation of the final sum due and owing. Discrepancies in calculation was no ground for non-application of estoppel in respect of specific acts or statements. D did not deny the non-existence of any notices or written documents to show that it disputed any of the invoices. Non-appropriation of Payment To Any Specific Invoices [18] An aspect of the defence case was that D “never paid on any specific invoices” as submitted by D/C or in other words, that D did not appropriate payment to any specific invoices. It followed them that D could not be stopped from disputing the invoices from the fact of payment. The law applicable to this situation is s. 62 of the Contracts Act, 1950 which states: “62. Application of payment where neither party appropriates Where neither party makes any appropriation, the payment shall be applied in discharge of the debts in order of time,… ” My attention was also drawn to the case of Nam Joo Hong Feedmills Sdn. Bhd. v. Soon Hup Poultry Farm [1985] 2 MLJ 206 where the court adopted 8 para 509, Vol. 9, Halsbury’s Laws of England on the right of appropriation which reads: “507. Account current. Prima Facie, the right of appropriation by the creditor does not arise in the case of an account current, that is to say, where there is one entire account into which all receipts and payment are carried in order of date, so that all sums paid in form one blended fund. In such a case the presumption is that the first item on the debit side of the account is intended to be discharged or reduced by the first item on the credit side, and that the various items are appropriated in the order in which the receipts and payments are set against each other in the account.”. [19] P in the instant case maintained only one account in which all receipts and payments are recorded in order of date. Hence, by adopting the aforesaid principle of accounting, it was submitted by Plaintiff that the sum of RM774,000.00 admittedly paid by D was in satisfaction of the invoices in order of time as set out in the Second Schedule to the SOC. I agree that P should now be estopped from questioning the invoices even though D had made payments in respect of the invoices in chronological order. This view was fortified by the fact the throughout the receipt of the series of invoices followed by payments no question arose as to the validity of the invoices even as late as when P issued the Notice of Demand to which no reply followed. In the recent Court of Appeal case of Yoong Sze Fatt v. Pengkalan Securities Sdn Bhd [2010] 1 MLJ 85, Low Hop Bing, HMR held: “In our judgment, if the defendant had really nothing to do with the account or the trading of the shares by his employer through the account… the defendant as a reasonable man would no doubt have at the earliest opportunity raised a complaint, protest or querry with the plaintiff in relation to the contract notes, contra statements and letter of demand sent to his home address. He had not done so. It is now too late in the day to deny liability after the commencement of the suit, a fortiori, in this appeal. The defendant’s conduct certainly calls for the application of the doctrine of estoppel.”. 9 Alleged Tampering of Invoices [20] Of the 7 disputed invoices, 5 were disputed on a further ground of tampering. For each of the aforesaid 5 invoices produced by P and marked as Exhibits P6A, P7A, P11A, P12A and P13A, which were all photocopies, D tendered a corresponding photocopy. The latter photocopies were marked Exhibits P6B, P7B, P11B, P12B and P13B. It was alleged that a significant difference between these 2 sets of invoices was proof of tampering. No further evidence was led to prove tampering as alleged. The difference that was purportedly proof was that P’s copies contained a rubber-stamp endorsement that read “Please Chop, Sign and Return this copy” whereas the copies exhibited by D didn’t. P’s copies also bore 2 other rubber-stamps, that of D and one Saga Forte Resources (M) Sdn. Bhd. (‘SF’). Quite obviously, P’s copies were different from those of D because the former were used for acknowledgment purposes. P also called a witness from SF to explain the presence of SF’s rubber-stamp on the invoices addressed to D, which D/C alleged was an afterthought upon evidence of tampering having been led. The essential question was whether there was in fact any evidence of tampering? [21] As the allegation of tampering was made by D, the evidential burden of proof of that particular fact was on D [S. 103, Evidence Act 1950]. It is a serious allegation of a criminal nature akin to fraud. Therefore, a high degree of proof is required to establish tampering by P, on whom there was no onus to disprove the fact unless sufficient evidence was adduced by D to discharge its evidential burden. [22] A fraudulent act is one done “with intent to defraud, but not otherwise” [s. 25, Penal Code]. The defence contention on tampering appears to imply that it was with the intention of defrauding D even though the vital contents of both sets of invoices are the same. It is trite law that where fraud is alleged in civil proceedings it must be proved beyond a reasonable doubt [Saminathan v. Pappa [1981] 1 MLJ 121, at p. 126; Boonsom Boonyanit v. Adorna Properties Sdn. Bhd.(C/A) [1997] 3 CLJ 17]. The evidence led by D on the present allegation, relying purely on a comparison of documents, without more, in my finding, fell far short of proof beyond doubt. There was a logical and reasonable explanation for the difference in the 2 sets of photocopies of the same documents and should 10 be accepted in the absence of proof to the contrary. It is noteworthy that the documents produced by P were all agreed documents within the knowledge of D and at no previous instance had any allegation of tampering been raised as to their contents. [23] A more crucial fact in regard to the present issue is that the allegation of tampering was never pleaded. It is settled law that only issues and facts that are specifically pleaded need to be considered by the court in adjudging a claim. The success or failure of a party’s case depends entirely on its pleadings and the evidence led in support thereof. It is not proper for a court to give judgment in a suit on material facts or issues not pleaded even though the evidence presented at a trial may give rise to a whole variety of facts and issues outside the ambit of pleadings. [ Bank Bumiputra (M) Bhd. v. Mahmud b. Hj. Mohamed Din, Datin Hajjah Salmah bt Md Jamin, Intervener [1990] 1 MLJ 381; Yen Wan Leong v. Lai Koh Chye [1990] 2 MLJ 152]. Order 18, Rule 8, Rules of the High court, 1980 states: “A party must in any pleading subsequent to a statement of claim plead specifically any matter, for example, performance, release, any relevant statute of limitation, fraud or any fact showing illegality – … (b) which, if not specifically pleaded, might take the opposite party by surprise;” D/C conceded that the issue of ‘tampering’ was never pleaded but argued that the law is clear on this point whereby evidence need not be pleaded and that the issue was being raised based on an evidential point only. Further, that as it was incumbent on P to prove its case and as doubt had arisen as to the validity of the invoices, the onus was on P to account for the tampering. Suffice to say that this line of argument was completely erroneous and contrary to established rules of pleadings. There is no basis whatsoever in law for raising an issue that was never pleaded purportedly from an evidential point. Tampering is a mere allegation and not evidence that need not be pleaded. The invoices were part of the bundles of 11 documents that had been duly exchanged between the parties and the set of invoices (copies) produced by D were in its possession. Hence, to argue that the issue of tampering only surfaced at the trial was clearly untenable on the available facts. [24] For the above reasons, I held that D’s contention that P’s invoices should be rejected as evidence on the ground of tampering was clearly without basis and untenable in law. Decision [25] In view of the foregoing, I found that P had, on a balance of probabilities, made out its claim, that the agreed sub-contract price should be calculated based on the quotation and purchase order in respect of ‘Bridge 1766’ while for ‘Bridges 1767 and 1768’ the price should be based purely on invoices issued and received by D without objection. By adopting this manner of calculation, the price for ‘Bridge 1766’comes to RM685,000.00 and not RM710,060.00 as pleaded as the parties’ stand was that the T & C of the S/C for this bridge were to be inferred from the quotation and P.O. Effect had to be given to the agreement which evinced the true intention of the parties. As such the claim had to be limited to the agreed price as deduced from these documents despite the invoices which gave a figure of RM710,060.00. However, in respect of the other 2 bridges, the agreed S/C price was dependant wholly on the invoices, none of which had been proved to be double-claims or tampered with as alleged. The price of RM472,530.00 as pleaded and determined from the invoices could be deemed as agreed on the evidence and thus, was binding and enforceable against D. This finding would answer the issues arising as regards scope of works, value of the sub-contract and the extent of D’s liability to P. [26] On the issue of estoppel, I would summarise that until this case was filed, D had not challenged or objected to any of the invoices issued by P and had made a series of payments into the running account of P maintained for the S/C. Hence, on the basis of all the evidence and records, D was now estopped from questioning the invoices to deny their 12 liability. For D to be allowed to do so would be unconscionable and inequitable under the existing circumstances. [27] As for tampering, it was a non-issue as it was neither pleaded nor listed as an agreed issue to be tried. In any event, the onus of proving the allegation rested with D but D had clearly failed to discharge the onus of proof as, inter-alia, no evidence in support had been led. [28] In conclusion, I found that while P had made out a case as pleaded, D had failed to prove the allegations against the truth and veracity of the invoices on which this claim was premised. I, thus, entered judgment for P for the sum adverted to above with costs and interest. Counter-claim [29] D has claimed against P under no less than seven heads which D was said to be entitled to under the sub-contract (‘S/C’). The basic question was whether D was entitled make these claims in this suit which was filed sometime in year 2009 when P had completed their works under the sub-contract way back in September 2007. Thereafter, no demands or claims had been made by D in respect of the works done by P. At no instance before the commencement of this action did D notify P that it intended to make any of the claims as per the counter-claim. When P’s solicitors issued the notice of demand dated 18.07.2008 for the sum now claimed, there was neither reply nor counter-demand from D. The only instance when D disputed the sub-contract sum was when P had completed the S/C works and made demands for payment for the balance towards the end of 2007. At a meeting arranged by KTM to resolve the dispute, D contested the sum claimed solely on the ground that the total S/C sum should be computed on the basis of the quantity of steel that had been used in the works. DW1, D’s sole witness, admitted this fact under cross-examination. At that point in time, no issue had been raised as to D’s entitlement to offset that sum against the instant claims for LAD, negligence and others, which appear to be an afterthought after P had commenced this suit for the balance payable by D. 13 Liquidated Assessed Damages (‘LAD’) [30] D/C submitted that based on DW1’s testimony and the documents exhibited D had proved that LAD had been imposed for late completion of the project and thus, D was entitled to claim the sum from P. As rightly submitted by P/C, the issue was not late completion and imposition of LAD but whether under the terms of the S/C, P could be held liable to pay compensation for the delay. [31] The S/C between P and D was for a specific type of works in the project that involved a variety of works and various stages for which several contractors had been engaged. No deadline had been imposed on P to complete the works under the T & C of the S/C. On this ground alone, the claim for LAD against P could be held unsustainable. Neither had any agreement been reached that in the event of delay LAD could be imposed on P. In other words, time did not seem to be at the essence. In any event, after D had completed the work, there was neither any allegation or complaint by D of delay nor claim for LAD. [32] It is noteworthy that P had been engaged to carry out the main work involved in the project-fabrication and installation of ‘Bridge 1766 vide PO dated 22.01.2007 [ Exhibit P4 ] – as late as some 9 months from the date of commencement of the project with only 3 months left for the scheduled completion. From D’s correspondence itself to KTM for extension of time to complete the project, D itself had delayed beginning the work on schedule. In applying for extension of time [ Exhibit D21 ], the reasons advanced attributed delay to a number of factors, such as wide spread flooding in Malacca, none of which concerned D. [33] PW1’s evidence that the S/C works had been completed in May 2007 and not in September was challenged by the defence on the ground of being in conflict with P’s own pleading that completion took place in May 2007. I agree that a party in not entitled to lead evidence in conflict with its own pleaded case. Be that as it may, the late completion, if any, did not make any difference as there was no agreed time-frame for P to complete the work. Neither had there been any objection been raised by D for late completion nor a notice issued within a reasonable time to claim for 14 damages or compensation for the delay citing specifically the consequential losses that D had sustained. [34] The project was finally completed on 05.02.2008, well after P had installed ‘Bridge 1766’ whether it was May or September 2007. The evidence showed that various other works to be carried out by other subcontractors after the installation had not been completed on schedule and thereby could have caused the delay. There was no clear evidence to prove that the delay which occasioned LAD being imposed on D was actually caused by D. Hence, the claim for P to be held liable for LAD was not proved. Derailment and Damage To Signal Cable [35] D relied on a report of derailment at ‘Bridge 1767’ [Exhibit D22] on 14.12.2006 in support of this claim. The Defence alleges that the signal cable was damaged at ‘Bridges 1767 and 1768’ while derailment occurred at ‘Bridge 1768’ on 10.03.2007. DW1 confirmed that it occurred at ‘1768’ contrary to the report D22. These clear contradictions themselves cast doubt on the veracity of this claim. In any event, the vital question was whether P had caused the above derailment and damage in the course of carrying out its work. P/C drew the court’s attention to D22 which was a contemporaneous document which clearly revealed the cause of the above derailment and damage to signal cable. The report concludes that the track contractor did not comply with specifications and structure at the bends of the tracks. Laying the tracks was no part of P’s work under the sub-contract as P was not the track sub-contractor. There was, therefore, no doubt that P could not be held liable for the current loss/damage and D’s evidence itself showed it was outside P’s scope of work. Negligence For Causing Cave In of Soil [36] DW1 confirmed that the cave in was to the track platform that involved the ballast that supported the track. When the cave in occurred, DW1 hired a tamping machine to strengthen the ballast. DW1 also confirmed that if there was any sinking of ground, the tracks or piling contractor would be responsible and that ballast work was the track 15 contractor’s responsibility. Neither ballast nor tracks was within P’s scope of sub-contract works. Hence, it was again clear that P could not be held liable for the above incident as there was no proof of P having caused it. Platforms and Cranes [37] D exhibited certain documents allegedly showing costs incurred for hiring cranes for P to install the bridge. DW1 admitted that D used cranes to load and unload sleepers at the site in the course of the next stage of work following installation of ‘Bridge 1766’, which includes ballast, sleepers and tracks. These are not within P’s scope of works. The relevant work order [Exhibit D19] tendered by D showed that the crane had been hired in July 2007 which was long after P had installed ‘Bridge 1766’. P did not issue any further invoices for work done after May 2007. [38] Exhibit D24 was the relevant Statement of Account tendered to support this claim addressed to D. It referred to invoices for the months of October 2007 and January 2008, by which time P had long completed installing ‘Bridge 1766’. A further invoice referred to was Exhibit D25 which was for hiring of excavator during July 2007. DW1 gave evidence that the excavator was used in relation to ballast and to construct embankment. Ballast work was not included under P’s sub-contract and therefore, P could not be held liable for costs incurred in respect thereof. [39] Similarly, as regards platform, apart from stating that it had been provided, it was not shown under which clause or term of the S/C, P was liable to compensate D for providing the platform. Hence, D had failed to prove this claim too. The Remaining Items [40] There was a total failure to prove the losses as set out and these items, therefore, needed no further consideration. 16 Conclusion [41] In deciding the counter-claim, regard must be had to the legal and evidential burdens of proof placed on the defendant (‘D’), who was in the same position as that of P in the main suit. The onus was on D to adduce sufficient evidence to prove all the items claimed, failing which P had no case to answer on these claims. In this situation, the evidential burden would not shift to P to rebut D’s evidence which in itself was lacking. As held in Cottage Home Sdn. Bhd. v. Wong Kau & Anor [2011] 1 LNS 411. “It is a fundamental principle in law that the party who asserts the existence of facts upon which a judgment should be given to him must prove the existence of these facts in accordance with section 101 of the Evidence Act, 1950’. [42] In view of the state of D’s evidence on the counter-claim, based on the foregoing grounds I found that D has failed to discharge the burden of proof to prove the particulars of any of the items claimed. Furthermore, the principles of estoppel would apply to estop D from asserting the claims at this belated stage when no prior notice had been given to do so until the commencement of this suit. The claims relate to matters or incidents occurring long after P had completed its contractual obligations under the sub-contract which appeared all along to be to the satisfaction of D. The doctrine of estoppel is of wide application as a defence open, inter-alia, to parties in a contractual relationship. In the case of Boustead Trading (supra) Gopal Sri Ram, JCA (sitting in the Federal Court) observed: “The time has come for this court to recognize that the doctrine of estoppel is a flexible principle by which justice is done according to the circumstances of the case. It is a doctrine of wide utility and has been resorted to in varying fact patterns to achieve justice. Indeed, the circumstances in which the doctrine may operate are endless.”. On the facts and evidence in this case, I found that the doctrine of estoppel could be invoked by P as a defence to the counter-claim. 17 [43] For the above reasons, I found the entire counter-claim to be without merit or basis and dismissed it with costs. Dated: 30th June 2011 ( GUNALAN A/L MUNIANDY ) Judicial Commissioner High Court of Malaya Johor Bahru. …………… for the Plaintiff Mr. Bala Gopal Messrs Bala Gopal & Associates Advocates & Solicitors Malacca. ..…………. for the Defendant Mr. Mohd Iqbal Messrs Idris & Partner Advocates & Solicitors Shah Alam, Selangor. 18