school-based assessment among esl teachers in

advertisement

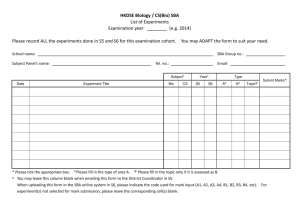

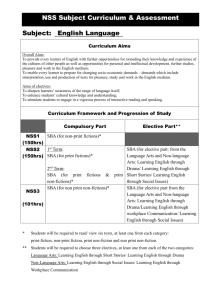

SCHOOL-BASED ASSESSMENT AMONG ESL TEACHERS IN MALAYSIAN SECONDARY SCHOOLS Chan Yuen Fook (Ph.D) Gurnam Kaur Sidhu (Ph. D) Faculty of Education, Universiti Teknolo MARA 40200 Shah Alam, Selangor, Malaysia yuenfookchan@yahoo.com Abstract: School-based assessment (SBA) is a process of monitoring, evaluating and implementing plans to address perceived weaknesses and strengths of the school. Today, policymakers and educators are looking towards SBA as a catalyst for education reform. Since the late 1990s and the beginning of 2000, SBA has slowly made its way into the Malaysian classrooms. Since then, there have been only a few studies that looked into the implementation of SBA in Malaysia. Therefore a study was conducted to investigate the knowledge and best practices of Malaysian ESL (English as a Second Language) teachers conducting the SBA. Such a study is deemed timely and crucial as it could provide a relevant picture for scholars, practitioners and policy makers in relation to testing and assessment. Descriptive research design was employed to examine the level of knowledge and best practices of ESL teachers in SBA. The study indicated that most of the respondents had acquired adequate knowledge in constructing their own tests, but one third of the respondents admitted that they often applied “cut and paste” method and they did worry about the validity and reliability of the tests constructed. This indicates that there are a number of existing problems in SBA that have to be addressed as soon as possible. Perhaps what is needed is a concerted effort and cooperation from all parties concerned. Keywords: School-based assessment, Knowledge, Best Practices, Secondary School Abstract: Pentaksiran berasaskan sekolah merupakan satu proses pemantauan, penilaian dan pelaksanaan pelan tindakan untuk menangani kelemahan dan kekuatan yang diperhatikan di sesebuah sekolah. Hari ini, pembuat polisi dan para pendidik melihat pentaksiran berasaskan sekolah sebagai pencetus kepada reformasi pendidikan. Sejak akhir tahun 1990an dan permulaan tahun 2000, pentaksiran berasaskan sekolah dengan perlahan-lahan telah meresap masuk ke dalam bilik darjah di Malaysia. Namun demikian, tidak banyak kajian telah dilaksanakan untuk mengkaji keberkesanan pelaksanaan pentaksiran berasaskan sekolah di Malaysia. Oleh itu, kajian ini telah dilaksanakan untuk mengkaji pengetahuan dan amalan terbaik guru Pengajaran Bahasa Inggeris sebagai Bahasa Kedua dalam mengendalikan pentaksiaran berasaskan sekolah. Kajian ini dianggap penting dan memenuhi keperluan semasa sebab ia dapat membekalkan satu gambaran yang relevan kepada sarjana pendidikan, pelaksana dan pembuat polisi tentang aspek pengujian dan pentaksiran. Penyelidikan deskriptif telah digunakan untuk mengenalspati tahap pengetahuan dan amalan terbaik guruguru Pengajaran Bahasa Inggeris sebagai Bahasa Kedua dalam pentaksiran berasaskan sekolah. Kajian ini menunjukkan bahawa kebanyakan responden telah menguasai pengetahuan yang cukup dalam mengendalikan ujian mereka, tetapi satu per tiga daripada responden mengakui bahawa mereka sering mengamalkan kaedah ‘gunting dan tampal’ dan mereka juga risau tentang kesahan dan kebolehpercayaan ujian yang dibina oleh mereka. 1 Dapatan kajian menunjukkan masih terdapat masalah-masalah dalam pentaksiran berasaskan sekolah yang perlu ditangani dengan segera. Kajian juga menunjukkan bahawa kerjasama erat dan sokongan penuh daripada pelbagai pihak adalah amat dialu-alukan demi menjayakan pelaksanaan pentaksiran berasaskan sekolah. Kata Kunci: Pentaksiran Berasaskan Sekolah, Pengetahuan, Amalan Terbaik, Sekolah Menengah INTRODUCTION For some time now, until the mid nineties testing in Malaysia has been rather centralised and summative in nature. Today, there is sufficient research and literature (Frederiksen, 1984; Cunningham, 1998; Dietel, Herman & Knuth, 1991; Borich & Tombari, 2004: 270) that has shown the shortcomings of one centralised summative examination. Such assessment mechanisms often influence what schools teach and it encourages the use of instructional methods that resemble tests. Besides that, teachers often neglect what external tests exclude. Therefore, there is a global move to decentralise assessments and this has seen the introduction of authentic alternative forms of assessments that are continuous and formative in nature. Since the late nineties and the beginning of 2000, SBA has slowly made its way into the Malaysian classroom. Nevertheless, in tandem with a global shift towards decentralised assessment, similar steps towards decentralising assessment have also been taken by the Malaysian examination bodies. Today, both policymakers and educators are now looking towards School-based assessment (SBA) as a catalyst for education reform. It is seen as a leverage for instructional improvement in order to help teachers find out what students are learning in the classroom and how well they are learning it. Such an opinion was articulated by the former Malaysian Minister of Education, Tan Sri Musa Mohamed on May 7, 2003 when he said that, “we need a fresh and new philosophy in our approach to exams . . . we want to make the education system less exam-oriented and (we) are looking at increasing SBA as it would be a better gauge of students' abilities.” The former Minister of Education, Tan Sri Musa Mohamed also pointed out that there would be greater reliance on SBA in the future. According to him, such a method of assessment would be in line with current practices in other countries such as the United States, Britain, Germany, Japan, Finland and New Zealand (Musa, 2003; Marlin Abd. Karim, 2002). Thus, the Ministry of Education in Malaysia has looked into ways on how this approach could be expanded to all levels of education. Furthermore, with greater reliance on SBA in the future, some major examinations may be abolished while some would have less bearing on students' overall grades. The Malaysian Examinations Syndicate (MES) holds the view that SBA is any form of assessment that is planned, developed, conducted, examined and reported by teachers in schools involving students, parents and other bodies (Adi Badiozaman, 2007). These kinds of school assessment can be formative throughout the teaching-learning process or summative at the end of it. Such as move would help teachers identify students’ strengths and limitations. The greater flexibility and reliability offered by SBA has seen the current shift towards decentralisation in school assessment. A similar shift is also seen creeping into the Malaysian schools. Malaysia is currently in the process of revamping its school system to 2 make it less exam-oriented. Consistent with global trends and in keeping with the government’s initiatives to improve the quality of human capital development efforts through a holistic assessment system, Malaysian Examinations Syndicate has introduced the National Educational Assessment System (NEAS). The NEAS proposed by the MES promotes a change from a one-off certification system to one that propagates accumulative graduation. In line with that, at an international forum organised by MES in 2007, the former Director of Examinations, Dr. Adi Badiozaman in his concept paper proposed that Primary Year 6 UPSR and the Secondary Three PMR may be abolished and these would be replaced by a broader and more flexible assessment system. This broader concept of assessment requires the assessors to be well-versed in the knowledge of other forms of alternative assessments such as observations, portfolios, peer and self assessments and projects. With the intended implementation of the new concept in the overall school assessment system, it is then the concern of many parties involved in the education system to review current practices and to be well prepared in this regard. The concept of assessment has to be vivid and clear to all, especially the teachers who are to be the implementers. STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM In line with the changing trends in assessment, SBA or PKBS (Penilaian Kendalian Berasaskan Sekolah) has been introduced into Malaysian schools under the New Integrated Curriculum for Secondary Schools (KBSM). It has adopted ‘coursework’ for a few subjects in secondary schools such as History, Geography, Living Skills and Islamic Education for the lower secondary classes and Biology, Chemistry and Physics for the upper secondary classes. Beginning 2003 the school-based oral assessment commenced for both Bahasa Malaysia and English Language. Today the school-based Oral English Test is a compulsory component for Secondary Five candidates taking the SPM Examination. Nevertheless, it cannot be denied that SBA is an approach to redesign assessment in schools. It gives all educational stakeholders, namely educators, parents, students and the community-at-large, the power to improve teaching and learning practices. By transferring SBA decisions to schools, educators are now empowered to help students perform better. SBA has a great appeal, as witnessed by the large number of countries all around the globe trying some form of it. Its results, however, have been rather slow as any change requires a paradigm shift for all stakeholders concerned. While some have enthusiastically boarded the ship, there are others who are still sceptical that the current wave of decentralisation could be just another swing of the pendulum. According to Brookhart (2002: 5), studies of “what teachers are or should be taught and what they know have generally concluded that teachers’ knowledge of large-scale testing is limited” especially in the important area of communicating assessment results to students, parents and administrators. The findings also indicated that teachers have limited skills at gathering and using classroom assessment information for improving student learning. In fact the findings of many other researchers have also concluded that courses in testing and measurement for teachers should increase emphasis on classroom assessment, and decrease emphasis on large-scale testing (Gullickson, 1993; Marso & Pigge, 1993; Stiggins, 1991; Brookhart, 2002). Thus, we must acknowledge the fact that if teachers possess low levels of knowledge in assessment they may not be able to help improve student learning. These teachers may feel overwhelmed and frustrated and consequently might display undesirable work behaviours 3 towards performing best practices in SBA. If efforts are not made to investigate and to improve the best practices of teachers in SBA, the noble aspirations that the Education Ministry hopes to achieve with the implementation of the SBAs may not be fulfilled. According to Rohizani Yaakub & Norlida Ahmad (2003), improving best practices of teachers in testing and assessment should be an important objective in order to improve the levels of their teachers’ knowledge in SBA. Unfortunately, until now there have not been many studies conducted to gauge the levels of knowledge and best practices of Malaysian ESL teachers in SBA. The need to measure the levels of knowledge and best practices of ESL teachers is even more pressing considering the importance of English language in today’s process of globalisation and the advent of the Information Technologies. Consequently, there is a need to understand further the levels of their knowledge and best practices implemented by ESL teachers in SBA because of the varying perceptions of teachers regarding this pertinent issue. Documenting ESL teachers’ opinions vis-à-vis knowledge and best practices in SBA is both timely and significant. Such a study is deemed timely and crucial as it could provide a relevant picture for scholars, practitioners and policy makers in relation to testing and assessment. OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY The purpose of this study was to examine the level of knowledge and best practices of ESL teachers in SBA as perceived by ESL teachers. The main selected factors were knowledge and best practices in SBA. Specifically, the objectives of the study were to: 1. Describe teachers’ levels of knowledge in SBA 2. Examine teachers’ best practices in SBA THE METHOD This is a descriptive study that examined the level of knowledge and best practices of ESL teachers in SBA. Henceforth a descriptive study was chosen to allow a qualitative and quantitative description of the relevant features of the data collected (Cohen, Manion & Morrison, 2003). It involved the use of a questionnaire and structured interviews. The questionnaire consisted of both close and open-ended questions that were used to obtain data both in quantitative and qualitative forms. Quantitative data was analysed by using SPSS package (version 13.0) to identify the mean and standard deviation of each item. The qualitative data was analysed both inductively and deductively to identify the main themes that emerged based on the research questions posed in this study. The target population of this study were secondary school teachers in two states (Negeri Sembilan and Melaka) in Malaysia. The study examined the level of knowledge and best practices of ESL teachers in SBA in the day-time secondary schools. Thus, the study was confined to eight randomly selected day-time secondary schools in the state of Negeri Sembilan and six randomly selected day-time secondary schools in the state of Melaka. Once the schools were identified the multistage cluster sampling method was applied (Cohen, Manion & Morrison, 2003). Each cluster involved the Head of Language Department, Head of English Language Panel and all the English Language teachers in the participating schools. 4 Respondents’ Demographic Variables A total of 97 respondents from the 14 schools were involved in this study. Demographic findings (Table 1) indicated that out of the 97 respondents, 83.5% of them were females and 16.5% were males. This is reflective of the fact that a majority of ESL teachers in Malaysian schools are females. As for the ethnic groups, the results indicated that 41.7% of the respondents were Malays, 34.4% Chinese, 21.9% were Indians and the remaining 2.1% were from other ethnic groups. In terms of academic qualifications, the results showed that 80.4% of the respondents had a Bachelor’s degree, 11.3% had a master degree, 7.2% possessed a Diploma or below, and only 1.0% had a Doctorate’s degree. Table 1: Gender, Ethnic and Academic Qualification of Respondents Variable Frequency (n=97) Percent 16 81 16.5 83.5 40 33 21 2 41.7 34.4 21.9 2.1 1 11 78 7 1.0 11.3 80.4 7.2 Gender Male Female Ethnic Group Malay Chinese Indian Others Academic Qualification Doctorate Degree Master Degree Bachelor Degree Others (Diploma/Certificate) The study also looked into the distribution of age, age group, teaching experience and classes or forms the respondents. The demographic analysis displays the frequency distribution, percentages, means and standard deviations of respondents according to the variables mentioned. The results showed that the age of the respondents ranged from 25-56 years with mean of 42.5 and standard deviation (SD) of 7.3. The findings indicated that the majority of the respondents (64.2%) were between 35-49 years. Less than 20% of the respondents were between 50-54 years, approximate to 11% were between 30-34 years and less than 5% were between 25-29 years and 55 and above. In examining teaching experience in the present school, the results revealed that 44.7% of the respondents taught English in the lower forms while another 55.3% taught in the upper forms. FINDINGS Planning the SBA The survey reveals that respondents had sufficient knowledge on many aspects of planning the SBA (Table 2). Respondents did not have problems in writing both the specific and general objectives for their lesson plans. The mean scores for the respondents’ ability to write the learning objectives are 3.32 and 3.33 respectively, while the standard deviations are 0.57 and 0.59. In relation to the ability to write good objectives, the respondents also 5 indicated that they did not have problems in interpreting the English language syllabus. The mean score is above average which is 3.38, and the standard deviation is 0.62. This is consistent with their ability to write good teaching objectives. The findings also disclosed that the respondents did not have problems in outlining instructional content (mean = 2.99, SD=.66) and objectives for the test (mean = 2.98, SD=.66). Furthermore, most of the ESL teachers in schools were competent in identifying instructional objectives and content for SBA. Apart from that, they should be able to identify the taxonomy of educational objectives. This is to determine the level of difficulty of assessment in accordance to the cognitive, affective and psychomotor domains. It is obvious that the respondents’ knowledge in the cognitive (mean=2.79, SD=.65), affective (mean=2.73, SD=.68) and psychomotor (mean=2.76, SD=.71) is at the satisfactory level. Thus, the results show that teachers were knowledgeable in developing a table of specifications (mean=2.88, SD=.69). A table of specifications is very important especially at the planning stage because it is like a plan for the preparation of a test paper. Table 2: Knowledge in Planning for SBA Knowledge in Planning the SBA Taxonomy of educational objective: cognitive Mean 2.79 Std. Deviation .65 Taxonomy of educational objective: affective 2.73 .68 Taxonomy of educational objective: psychomotor 2.76 .71 English language syllabus 3.38 .62 Writing general objective for lesson plan 3.32 .57 Writing specific objective for lesson plan 3.33 .59 Developing table of specification for test 2.88 .69 Outlining instructional content for the test 2.99 .66 Listing instructional objectives for the test 2.98 Scale: 1 = very limited, 2 = limited, 3 = sufficient, 4 = very sufficient .67 Developing the SBA Results from questionnaire survey (Table 3) show that the English Language teachers rated themselves as knowledgeable with regards to the construction of MCQ (multiple choice questions) items on several language components, vis-à-vis; in reading comprehension (mean=3.24, SD=.60), grammar (mean=3.23, SD=.63), language forms and functions (mean=3.20, SD=.65), and language in use (mean=3.17, SD=.62). Besides that, most of the respondents also indicated that they had sufficient knowledge in constructing MCQs based on literary texts (mean=3.00, SD=.67). The responses have high mean scores of 3 and above. This indicates that their knowledge in constructing MCQ items on the listed components is sufficient. On top of that, the respondents also did not have problems in preparing the answer 6 keys for MCQ items (mean=3.15, SD=.69). Again, a high mean score of 3.00 and standard deviation 0.76 reveals that the respondents knowledge in the construction of MCQ items construes with their knowledge in scoring the test papers. The mean scores for their knowledge on the construction of open-ended cloze test (mean=3.14, SD=.64), guided composition (mean=3.21, SD=.64) and free writing (mean=3.14, SD=.66) are all above 3. The respondents also did not have problems in developing analytic scoring rubrics (mean=2.84, SD=.75) and holistic scoring rubrics (mean=2.86, SD=.73) for essay questions. Overall, the findings show that teachers do have sufficient knowledge in scoring essay questions (mean=3.00, SD=.65). Table 3: Knowledge in Developing the SBA Knowledge in Developing and Administering the SBA Mean Constructing MCQ in reading comprehension 3.24 Constructing MCQ in language forms & functions 3.20 Constructing MCQ in language in use 3.17 Constructing MCQ in grammar 3.23 Constructing open-ended questions in cloze text 3.14 Constructing open-ended question in guided composition 3.21 Constructing open-ended question in free writing 3.14 Constructing MCQs based on literary texts 3.00 Constructing questions for listening components 2.91 Constructing questions for speaking components 2.97 Reviewing & assembling classroom test according to format 3.13 Preparing answer keys for MCQs 3.15 Developing analytic scoring rubrics for essay questions 2.84 Developing holistic scoring rubric for essay questions 2.86 Administering the classroom test 3.26 Scale: 1 = very limited, 2 = limited, 3 = sufficient, 4 = very sufficient Std. Deviation .60 .65 .62 .63 .64 .64 .66 .67 .65 .62 .60 .69 .75 .73 .75 Respondents also reported having sufficient knowledge in test preparation with regards to aspects such as the construction of questions for the speaking (mean=2.97, SD=.62) and listening components (mean=2.91, SD=.65). The respondents had sufficient knowledge in reviewing and assembling classroom assessment according to the proper order and format (mean=3.13, SD=.60). At this stage they should be compiling, editing and setting the paper according to the appropriate format before administering the test paper. Apparently, respondents did rate their knowledge in administering classroom test as sufficient (mean=3.26, SD=.75). Hence, it can be concluded that, the respondents understood and knew the principles of constructing both objective (MCQ items) and subjective questions (openended) which was based on the syllabus and lessons they had taught. Scoring, Reporting and Analysing the SBA Even though respondents indicated that they had sufficient knowledge in planning and developing MCQs and essay questions as well as administering the test, findings in the study however reveal that respondents still did not possess sufficient knowledge for the successful implementation of SBA. The results (Table 4) show that they had limited knowledge in analyzing the score and conducting item analysis. The respondents’ knowledge in analysing 7 and interpreting the scores reflected that they were not familiar in calculating the mean (mean=2.52, SD=.80), standard deviation (mean=2.31, SD=.79), z-score (mean=2.19, SD=2.2) and t-score (mean=2.02, SD=.67). It can be deduced that the respondents most probably did not have practise in interpreting the scores because if they did, they would not rate their level of knowledge in this aspect as ‘limited’. This lack of knowledge in interpreting the scores in the form of basic statistics resulted in poor reporting of test scores (mean=2.39, SD=.81). Table 4: Knowledge in Scoring, Reporting and Analyzing the SBA Knowledge in Scoring, Reporting and Analyzing the SBA Mean Scoring the MCQ 3.00 Scoring essay questions 3.00 Calculating mean 2.52 Calculating standard deviation 2.31 Calculating difficulty index 2.20 Calculating discrimination index 2.15 Calculating t-score 2.02 Calculating z-score 2.19 Reporting score 2.39 Forming item bank 2.48 Scale: 1 = very limited, 2 = limited, 3 = sufficient, 4 = very sufficient Std. Deviation .76 .65 .80 .79 .72 .67 .67 2.20 .81 .68 Another obvious indicator of the respondents’ limited knowledge relates to item analysis data. They rated their knowledge in calculating the indices of difficulty (mean=2.20, SD=.72) and discrimination (mean=2.15, SD=.67) as very limited. Furthermore, the lack of knowledge in data analysis is evident as the respondents did not maintain an item bank as their knowledge is still limited (mean=2.48, SD=.68). In conclusion, it can be said that respondents had limited knowledge in reporting the score and analysing the data of the test. In addition, they also had limited knowledge in setting up an item bank (mean=2.48, SD=.68). Best Practices in SBA Today SBA is an integral part of the teaching and learning process. Therefore all teachers should possess a good understanding of SBA as a good knowledge of it would lead to the implementation of best practices at different stages in SBA. Such a move would certainly lead to the success of students in the learning process. Thus, the third part of the questionnaire investigated the TESL teachers’ best practices in a variety of aspects in SBA. Planning Stage The main goal of classroom assessment is to obtain valid, reliable, and useful information concerning student achievement. This requires determining what is to be measured and then defining it precisely so that tasks that require the intended knowledge, skills and understanding while minimizing the influence of irrelevant or ancillary skills can be constructed. A good planning of the test makes expected learning outcomes explicit to students and parents and shows the types of performances that are valued. The likelihood of 8 preparing valid, reliable and useful classroom assessments was greatly affected in this study due to certain identified drawbacks. The results (Table 5) showed that only 69.9% of the respondents prepared a tentative list of instructionally relevant learning outcomes and only 63.3% of the respondents listed beneath each general instructional objective a representative sample of specific learning outcomes that describe the terminal performance students are expected to demonstrate. Even though a majority of the respondents said that they stated instructional objectives in terms of students’ terminal performance (86.8%) and at the end of instruction (75.6%), and they are able to state general objectives (67.7%) and specific learning outcomes (91.2%) correctly, confusion could be detected in their responses. Many respondents (>80%) admitted that they did state their instructional objectives in terms of teacher performance (84.9%), learning process (90.3%), course content (85.6%) or stating two or more objectives in one objective (89.1%). Table 5: Best Practices in Planning the SBA Do you do the following when you are planning the SBA? Prepare a tentative list of instructionally relevant learning outcomes. List beneath each general instructional objective a representative sample of specific learning outcomes that describe the terminal performance students are expected to demonstrate. Begin each general objective with a verb (e.g., knows, applies, interprets). Omit “The student should be able to . . .” Begin each specific learning outcome with an action verb that specifies observable performance (e.g., identifies, describes). State instructional objectives in terms of: teacher performance. learning process. course content. two or more objectives. students’ terminal performance. at the end of instruction. Review the list for completeness, appropriateness, soundness and feasibility. Develop a table of specifications to identify both the content areas and the instructional objectives we wish to measure. Use your test and assessment specifications as a guide. Yes (%) 69.9 63.3 67.7 91.2 84.9 90.3 85.6 89.1 86.8 75.6 47.9 61.4 48.9 Furthermore, the findings in this study indicated that only 61.4% respondents developed a table of specifications to identify both the content areas and the instructional objectives they wished to measure. However, only less than half of the respondents used their table of specifications as a guide (48.9%) and review the list for completeness, appropriateness, soundness and feasibility (47.9%). One has to understand that to ensure that classroom tests measure a representative sample of instructionally relevant tasks; it is of utmost importance to develop specifications of test items and assessment tasks based on the different cognitive domains. 9 Constructing Stage It can be seen from the result of 81.1% of the respondents did prepare test items well in advance (Table 6). This is a good practice for such a move gives teachers ample time to review or edit the paper to produce a good test paper. This is supported by the evidence that 86.5% of the respondents did edit, revise and recheck the paper for relevance. Findings also indicated that 90.3% of the respondents ensured that the test items and the tasks were appropriate to their students’ reading level. This was supported by the fact that that 75.3% of the respondents were aware of the elements of validity so much so they agreed that the item constructed would be recognised by experts. Most of the respondents (62.2%) indicated that they are aware of the importance of writing each item that does not provide help in responding to other item. Close to 89.0% of the respondents agreed that the test item and assessment to be performed is clearly defined and it calls forth the performance described in the intended learning outcome. Table 6: Best Practices in the Construction of SBA Do you do these when you are constructing the items for SBA? Copy all the items from the suitable reference books. Write more items and tasks than needed. Write the items and tasks well in advance of the testing date. Write each test item and assessment task so that the task to be performed is clearly defined and it calls forth the performance described in the intended learning outcome. Write each item or task at an appropriate reading level. Write each item or task so that it does not provide help in responding to other items or tasks. Write each item so that the answer is one that would be agreed on by experts or, in the case of assessment tasks, the responses judged excellent would be agreed on by experts. Whenever a test item or assessment task is revised, recheck its relevance. Yes (%) 38.9 39.3 81.1 89.0 90.3. 62.2 75.3 86.5 On the other hand, more than half of the respondents (60.7%) indicated that they did not prepare more items and tasks than needed due to time constraints and a heavy workload in school. This finding was further validated in the interviews. In the interview sessions, five teachers stated that they had more than 25 periods per week plus other administrative tasks such as being the subject head and co-curricular adviser. However, teachers need to understand the fact that extra items are important especially at the review stage. Should there be any faults with the items selected earlier, then these extra items will be very useful. Furthermore the unused items can always be added to the item bank for future use. Such a practice is not taking place in schools as earlier results already indicated that respondents did not have adequate knowledge to set up item banks. In principle, teachers should construct their own items instead of practising the cut and paste technique. However, slightly more than a third of the respondents (38.9%) admitted that they often took test items from reference books. This fact was confirmed by a majority of the teachers during the interview sessions. Teachers admitted that this was a common practice as there is an abundant supply of ‘good reference books’. Teachers cited time constraint and lack of knowledge as the two main reasons for resorting to using items from reference books. 10 Nevertheless a majority of the teachers emphasised that even though they referred to reference books, they always made sure they chose and adapted questions to suit their students’ proficiency levels. Administering Stage A majority of them (96.5%) observed the basic principles of test administration (Table 7). This is proven in the high percentage for every item responded, the lowest being 86.7% and the highest 98.9%. While administering the test papers, a majority of the respondents having the experience as examination invigilators tried to keep interruptions to a minimum (97.8%) and also highlighted the fact that they did not indulge in unnecessary talk (92.1%). This is to maintain the reliability of test administration. In relation to that, respondents (95.6%) would keep the test reliable by not allowing any form of cheating to occur. By right, teachers should always be alert while carrying out their duty as invigilators. There are too many tricks that students can do in their attempt to cheat in a test. Besides that, the respondents (89.0%) were aware that they should not provide clues or hints to the questions. Respondents also knew their other duties and roles before administering the test papers. They reviewed the test papers for errors (95.5%) and made sure instruction or directions were clear and concise before assembling them for administration (98.9%). Table 7: Best Practices during the Administration of SBA Do you do the following when administering SBA? When you are administering the assessment, you abide by these rules and regulations: Do not talk unnecessarily before letting students start working Keep interruptions to a minimum Avoid giving hints to students who ask about individual items Discourage cheating, if necessary Review and assemble the classroom test Ensure the directions are clear and concise Administer the classroom test professionally Yes (%) 92.1 97.8 89.0 95.6 95.5 98.9 96.5 The interview sessions also looked into teachers’ perception as to the quality and administration of SBA in relation to national standardised tests. Approximately 90% of the respondents reported that they often ensured classroom assessments matched the needs of national standardised examinations so that their students will be familiar with the actual examination format. These teachers also stressed that aspects such as content, administration and scoring were strictly adhered to and complied with national high-stake examinations. Scoring Essay Questions for SBA In scoring the essay questions, respondents did agree that they adhered to the basic principles in scoring and grading the scripts (Table 8). A high percentage of between 86.8% to 96.3% responses to the respective items revealed that they were aware of the good procedures in scoring and grading. Firstly, most of the respondents (89.0%) prepared an outline of the expected answer in advance before constructing an answer rubric. Most of the teachers 11 (93.4%) made sure they use the scoring rubric that is most appropriate. They also decided and considered how to handle factors that were irrelevant to the learning outcomes being measured (86.8%). As they marked the papers, they (91.2%) went through one question at a time before marking the other. Majority of the teachers (94.6%) also marked the papers without knowing the name of the students. This is a good practice in order to avoid bias and maintain fairness in scoring. In addition, the respondents (83.9%) also practiced moderation of the scores obtained by having independent ratings before finally grading the test papers. Table 8: Best Practices in Scoring Essay Questions for SBA Do you do the following when scoring essay questions for SBA? Yes (%) While scoring essay questions, you assure the following: Prepare an outline of the expected answer in advance. Use the scoring rubric that is most appropriate. Decide how to handle factors that are irrelevant to the learning outcomes being measured. Evaluate all responses to one question before going on to the next one. When possible, evaluate the answers without looking at the student’s name. If especially important decisions are to be based on the results, obtain two or more independent ratings. Grading the test 89.0 93.4 86.8 91.2 94.6 83.9 96.3 Analysing and Interpreting the Test Score for SBA From the findings (Table 9), it can be concluded that most respondents did very basic analysis and interpretation of the score. The most that respondents did was to total up the score. This is usually followed by calculating the mean. Only 51.7% of the respondents did this. This is perhaps true of teachers in schools as many do not need to report the results in terms of mean or standard deviation (33.7% did this). The results also show that only very few teachers attempted to analyse standardised test scores such as t-score (22.5%) and z-score (20.5%) to identify a student’s actual performance in a particular subject in a class. Table 9: Best Practices in Analysing Test Scores for SBA Do you do the following when analysing the test score for SBA? Scoring the MCQ test by calculating: The total of the score The mean of the score The standard deviation of the score The t-score The z-score The difficulty index of the items The discrimination index of the items 12 Yes (%) 100.0 51.7 33.7 22.5 20.5 33.3 26.3 Another finding is that only a very small percentage of the respondents analysed the data to determine the difficulty index (33.3%) and discrimination index (26.3%). Then there is only the question as to why the percentage of the responses conducting the index of difficulty and index of discrimination did not tally. As it is, if one did the analysis of data, he would automatically calculate the two indices together. This points to the fact that respondents probably either did not understand what is meant by these two terms or they did not respond honestly to these items. Reporting the Test Score for SBA In Malaysian schools it is a common practice that teachers report mostly to students (92.2%) and parents (83.5%) as stated in Table 10. This is because Form teachers have to prepare report cards as feedback on students’ performance for parents. Findings further indicate that 60.7% of the respondents agreed that they sent reports to the district and 58.1% sent reports to the state education department. Normally, these reports are only for public examinations like the PMR, SPM and STPM. This finding relates to what the respondents knew about basic statistics and data analysis with regards to interpreting and analysing the scores. Table 10: Best Practices in Reporting Test Scores for SBA Do you do the following when reporting the test score for SBA? Report the test score to: Students Parents The district education office The state education department Use results for the improvement of learning and instruction Form the item bank Yes (%) 92.2 83.5 60.7 58.1 95.5 28.2 Apart from that, 95.5% of the respondents agreed that they used the results to improve learning and instruction. By analysing the assessment results, a teacher can diagnose the strengths and limitations of their students’ performance. A good teacher is one that is reflective and improves instruction based on the exam results. As for the item bank, 28.2% of the respondents revealed that they did have an item bank. This percentage is considered small but nevertheless, the setting up of a item bank is an important aspect in testing and assessment and it is something that all schools and teachers should practise. Interview sessions with respondents revealed that they all agreed that SBA results were used in improving the teaching and learning process. A large majority (95%) also admitted that assessment results most certainly gave valuable feedback as to the strengths and limitations of their students. However, 80% admitted to actually using these results for further enhancement of the teaching and learning process. Time constraints and the rush to complete the syllabus were cited as the main reasons that hindered ESL teachers’ to use SBA results to enhance student learning. 13 DISCUSSION OF FINDINGS Teachers in this study were also aware of the pros and cons of SBA. They were articulate as to the benefits of SBA stressing that it helps to provide them with information and insights needed to improve teaching effectiveness and learning quality. Teachers were also very aware that SBA encouraged classroom assessment to be an ongoing process. As such they felt learning is more meaningful to students as they can obtain immediate feedback on their performance. According to Jonassen (1988) feedback is an important aspect that assists learners in monitoring their understanding. Approximately 80% of the respondents admitted to using test scores for further enhancement of the teaching and learning process. A number cited time constraints, the rush to complete the syllabus, heavy teaching load and administrative duties that hindered them from using SBA results to enhance student learning. On the other hand, the study also indicated that ESL teachers possessed limited knowledge in a number of aspects such as interpreting test scores, conducting item analysis and forming a test bank. Teachers admitted that though they were familiar in calculating the mean, other calculations and terms like standard deviation, z-score and t-score were beyond their means. A number of them informed the researchers that they had heard of these terms during training but since their current job specifications did not require them to look into these aspects; they had forgotten their meanings and functions. A large majority of the ESL teachers were also not familiar with terms such as norm-referenced, criterion-referenced, formative and summative assessments. The mean scores on these items ranged from 10.5% to 23.3%. Terms like validity and reliability which are important aspects in testing and assessment also eluded a large majority. Only 10-14% of the respondents responded correctly to these items. In terms of best practices in SBA, a large majority of the respondents did prepare test items well in advance as this would give them sufficient time to review or edit the paper. The situations of lack of training and lack of positive responses to training in Malaysia are quite similar to what is experienced in advanced countries like the United States. According to Cromey and Hanson (2000), coordinating assessment activities and aligning them with a common "vision" for student achievement is rather demanding work for schools in the United States, particularly when, as research has consistently shown, few teachers and administrators have received formal training in assessment (Stiggins, 1995; Stiggins & Conklin, 1992; Wise, Lukin, & Roos, 1991). The national organisations, the research community, and state and local education agencies have attempted to provide guidance to schools regarding the use of student assessments. Nevertheless, it is not well understood how, or how well, schools are utilizing this support. Therefore schools must implement assessment systems that are not only aligned and integrated with the curricula, instructional practices and professional development strategies, but also contribute to the goal of increasing student achievement based on rigorous content standards. This is complex, demanding work that can last several years. Similarly, managing, synthesising, interpreting and using student assessment data obtained from a multifaceted assessment system can be a daunting task for educators, particularly when (a) the assessment system lacks coherence; (b) school staff do not have training or experience in student assessment; and (c) the time, attention, and energies of teachers and administrators are stretched to personal limits (Cromey & Hanson, 2000). Dwelling into the issues and challenges facing ESL teachers in SBA, a large majority felt the implementation left much to be desired. Even though teachers were aware of the positive 14 effects of SBA they cited time constraints and a heavy teaching load as the main culprits in its effective implementation. Issues of reliability and validity of school-based tests were also raised. Clearly, there are responsibilities associated with the data collection and use of assessment information. Hence, all the teachers should realise that assessment of students will not constitute productive use of time unless it is carefully integrated into a plan involving instructional action. Thus, it is important in a school system to constantly assess the quality of instruction, learning and assessment provided in its schools and to take account of the findings of research in establishing its benchmarks and policies (Hempenstall, 2001). RECOMMENDATIONS The findings of this study imply that the implementation of SBA in Malaysia with regards to the oral English assessment has its share of best practices and gaps that need to be addressed. Given below are some recommendations that could aid in the more effective implementation of the SBA. A large majority (70%) of the ESL teachers in the case study felt they lacked exposure to SBA and felt that any form of training in SBA would be welcomed. One has to understand the fact that any change in policy requires effective training to be provided to all parties concerned. For effective implementation of SBA, training should be on-going in the form of briefings, courses or workshops. Respondents in this study who had gone for training in SBA lamented on the fact that the course and exposure offered at school level was insufficient as the Ministry used the Cascade Model for training. Those who went for training at the national level were exposed to a weeklong training stint whereas at state level training was held for three days and at school level, training ranged from 1-day to 1 hour. A similar sentiment was also voiced by respondents with regards to the recent changes in the school-based oral assessment for PMR and SPM candidates at the Lower Secondary Three and Upper Secondary Five levels respectively. Many felt that providing them with a booklet of the new format did not give a good idea of what was expected. As such interpretations varied from one teacher to another and from one school to another. Hence there is a need for more frequent briefings and workshops for teachers to get hands-on training and exposure to SBA. Effective implementation of any new policy requires effective monitoring and feedback. Interview sessions with respondents indicated that there was little monitoring and supervision with regards to SBA. Monitoring in the school-based oral assessment for ESL teachers is usually conducted by the English language panel head or the Head of the Arts Department. Respondents indicated that many a time both these teachers lacked the knowledge of SBA to help provide effective feedback. Even though the MOE’s School Inspectorate Division officers are also responsible for carrying out monitoring, respondents indicated that hardly any of them had provided any feedback into SBA. It was also learnt that regional coordinators (RCs /Pentaksir Kawasan) who are either senior ESL teachers or principals are also appointed by each district to help monitor the implementation of school-based oral assessment. All the schools in this study had not been visited by any RC. Hence, steps must be taken to ensure school top management especially the school principal and the senior assistants be trained to monitor and supervise teachers with regards to SBA. School principals as instructional leaders in the school must play their role to take effective 15 monitoring and supervision measures. More importantly, effective support mechanisms must be provided for teachers who need help. All these findings cited above indicate that perhaps the time has come for the authorities concerned to look into ESL teachers’ workload. A reduction in workload and a decrease in the number of student enrolment may be steps in the right direction to ensure effective implementation of SBA. Regarding the increase in paper and administrative work such as filling in forms, cards and report books, a large majority of the respondents felt schools should be provided with more office personnel to help reduce their workload. In the light of recent changes in education and a move towards formative SBA, there is a need for a review the implementation of SBA. Effective implementation of SBA requires a set of procedures which applies minimum professional requirements to each level of personnel involved in the process of SBA. Furthermore schools should also move toward the establishment of a network of professional personnel with various levels of responsibility in each school. This network of professional personnel should form a central examining board with trainers to help implementers at the school level. In line with the continuous and formative training at school level, school administrators must ensure regular SBA coordination meetings are held to monitor and evaluate SBA practices. CONCLUSION Good assessments are those that focus on students and their learning. Mitchell (1992) in her book "Testing for Learning" argued for new methods of assessing performance, and asserted that the use of SBA can have a significant impact on teaching style and student achievement. Rather than just the traditional written tests, teachers will need a number of different ways for assessing both the product and process of student learning especially in the teaching of the English language. Good knowledge acquired by the teachers and their best practices will definitely enhance the teaching and learning of the English language subject. Henceforth there is a need for the Ministry of Education to ensure that sufficient in-depth exposure courses are provided to ESL teachers. The current Cascade Training Models is not working well and teachers need hands-on experience in testing and assessment in order to ensure best practices are shared and carried out. Furthermore, ESL teachers are challenged with a new paradigm shift in the current ESL classroom. Teachers have to be innovative and creative to include both the literature component and the Oral English test into their everyday ESL classrooms. In such a situation continuous on-going formative assessment seem to be the call of the day. Only then can one expect to witness an improvement in students’ performance and teacher instruction. 16 REFERENCES Adi Badiozaman Tuah. (2007). National Educational Assessment System: A proposal towards a more holistic education assessment system in Malaysia. International Forum on Educational Assessmnt System organised by the Malaysian Examinations Syndicate, 8 May 2007, Sunway Resort Hotel, Petaling Jaya. Borich, G.D., & Tombari, M.L. (2004). Educational assessment for the elementary and middle school classroom. New Jersey: Pearson, Merill Prentice Hall. Brookhart, S.M. (2002). What will teachers know about assessment, and how will that improve instruction? In Assessment in educational reform: Both means and end, ed. R.W. Lissitz., & W.D. Schafer, pp. 2-17. Boston: Allyn and Bacon. Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2003). Research methods in education. New York: Routledge/Falmer. Cromey, A., & Hanson, M. (2000). An exploratory analysis of school-based student assessment systems. North Central Regional Educational Laboratory. Learning Point Associates. http://www.ael.org/dbdm/resource.cfm?&resource_index=9. Accessed on 7 July 2007. Cunningham, G.K. (1998). Assessment in the classroom: Constructing and interpreteing tests. London: The Falmer Press. Dietel, R.J., Herman, J.L., & Knuth, R. A. (1991). What does research say about assessment? Oak Brook: North central Regional Educational Laboratory http://www.ncrel./org/sdsaraes/stw_esys/4assess.htm. Accessed on 7 July 2007. Frederikesen, N. (1984). The real test bias: Influences of testing on teaching and learning. American Psychology, 39(3), 193-202. Gullickson, A.R. (1993). Matching measurement instruction to classroom-based evaluation: Perceived discrepancies, needs, and challenges. In Teacher training in measurement and assessment skills, ed. S.L. Wise, pp. 1-25, Lincoln, Neb.: Buros Institute of Mental Measurements, University of Nebraskla-Lincoln. Hempenstall, K. (2001). School-based reading assessment: Looking for vital signs. Australian Journal of Learning Disabilities, 6, 26-35. Jonassen, D. (Ed.) (1988). Instructional design for microcomputer courseware. Lawrence Erlbaum: New Jersey. Marlin Abd. Karim. (2002). Pentaksiran berasaskan sekolah: Pentaksiran untuk pembelajaran. Prosiding Persidangan Kebangsaan Penilaian Kemajuan berasaskan Sekolah 2002. Anjuran bersama Unit Penyelidikan Asas, Pusat Pengajian Ilmu Pendidikan, Universiti Sains Malaysia dan Bahagian Perancangan dan Penyelidikan dasar Pendidikan, Kementerian Pendidikan Malaysia. 17 Marso, R.N., & Pigge, F.L. (1993). Teachers’ testing knowledge, skills, and practices. In Teacher training in measurement and assessment skills, ed. S.L. Wise, pp. 129185, Lincoln, Neb.: Buros Institute of Mental Measurements, University of Nebraskla-Lincoln. Mitchell, R. (1992). Testing for learning: How new approaches to evaluation can improve. American Schools. New York: Macmillan, Inc. Musa, M. (2003). “Malaysian education system to be less exam oriented”. New Straits Time, 8 May 2003. Rohizani Yaakub & Norlida Ahmad (2003). Teknik alternatif menilai dalam bilik darjah. 2nd International Conference on Measurement and Evaluation in Education (ICMEE 2003). Organized by School of Educational Studies & Centre for Instructional Technology & multimedia, Universiti Sains Malaysia. Stiggins, R. J. (1991). Relevant classroom assessment training for teachers. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 10 (1), 7-12. Stiggins, R. J. (1995). Assessment literacy for the 21st century. Phi Delta Kappan, 77(3), 238-245. Stiggins, R. J., & Conklin, N. F. (1992). Classroom assessment practices. In teachers' hands: Investigating the practices of classroom assessment. State University of New York Press: Albany, NY. Wise, S. L., Lukin, L. E., & Roos, L. L. (1991). Teacher beliefs about training in testing and measurement. Journal of Teacher Education, 37-42. 18