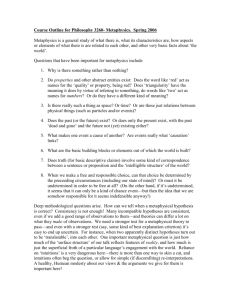

MSWord - EFN.org

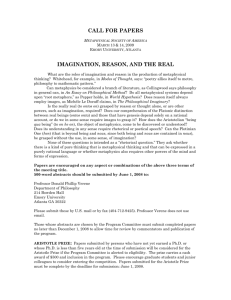

advertisement