CONTENTS - Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation Transportation

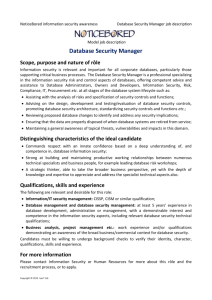

advertisement