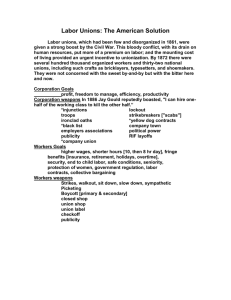

Workers are Exploited

advertisement

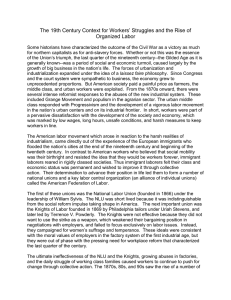

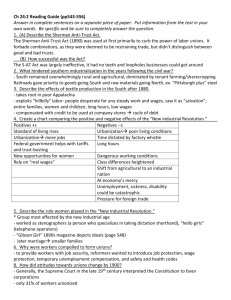

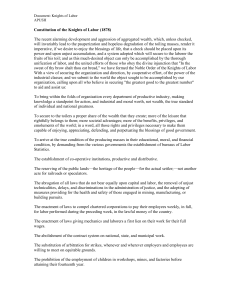

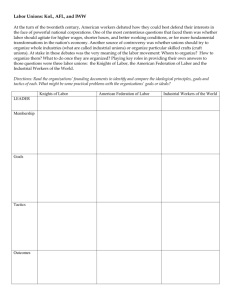

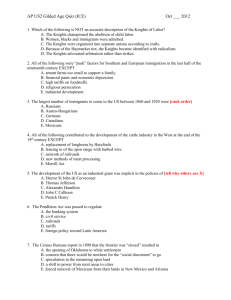

Workers are Exploited Union: organization of workers Long Hours and Danger: Seamstresses, like factory workers in most industries, worked 12 or more hours a day, six days a week. One of the largest employers, the steel mills, often demanded a seven-day workweek. Employees were not entitled to vacation, sick leave, unemployment compensation, or reimbursement for injuries suffered on the job. Yet injuries were commonplace. In 1882, an average of 675 laborers were killed in work-related accidents each week. In 1890, the fatality rate for railroad workers was 1 in 300. Many of these were brakemen, who had to balance on the ice roofs of speeding railroad cars. Hazardous working conditions abounded in other industries as well. Factories often were dirty, poorly ventilated, and poorly lit; workers had to perform repetitive, minddulling tasks hour after hour, often with dangerous or faulty equipment. Women and Children: Workers had little choice but to put up with the deplorable conditions in sweatshops. In addition, wagers were so low that most families could not survive unless everyone held a job. Between 1890 and 1910, for example, the number of women working for wages doubled, from 4 million to more than 8 million. Twenty percent of the boys and 10 percent of the girls under age 15- some as young as five years oldalso held full-time jobs. Many of these children worked from dawn to dusk, wasted by hunger and exhaustion that made them prone to crippling accidents. With little time or energy left for school, child laborers forfeited their futures to help their families make ends meet. The reformer Jacob Riis described the conditions faced by “sweaters” in tenement workshops. “The bulk of the sweater’s work is done in the tenements, which the law that regulates factory labor does not reach. . . In them the child works unchallenged from the day he is old enough to pull a thread. There is no such thing as a dinner hour; men and women eat while they work, and the “day” is lengthened at both ends. . . far into the night.” Most of the work available to women and children was tedious and required few skills; not surprisingly, these jobs paid the lowest wages- often as little as 27 cents for a child’s 14-hour day. In 1899, for example, women earned an average of $269 a year, nearly half men’s average pay of $498. The very next year Andrew Carnegie made $23 million- with no income tax. Labor Unions Emerge National Labor Union: The concept of labor unions wasn’t a new one. Skilled workers had had small local unions since the early 1800’s. The first large-scale national organization of laborers, the National Labor Union (NLU), was formed in 1866 by an ironworker named William H. Sylvis. The NLU consisted of about 300 local unions in 13 states. To make the union as representative and effective as possible, Sylvis urged local chapters to admit women and African Americans. Although carpenters and cabinetmakers agreed to open their locals to African Americans, other union refused, leading to the creation of the Colored National Labor Union (CNLU). Nevertheless, NLU membership grew to 640,000; and in 1868, the NLU persuaded Congress to legalize an eight-hour day for government workers. The union gained enough momentum to form its own political party- the Labor Reform Party- and to run its own candidate in the 1872 presidential election. Knights of Labor: While NLU organizers concentrated mainly on linking existing local unions, Uriah Stephens focused his attention on individual workers and, in 1868, organized the Noble Order of the Knights of Labor. Its motto was “An injury to one is the concern of all.” Membership in the Knights of Labor was officially open to all workers, regardless of race, gender, or degree of skill. Like the NLU, the Knights supported an eight-hour workday and advocated “equal pay for equal work” by men and women. They saw strikes, or refusals to work, as a last resort and instead advocated arbitration, or settlement of disagreements by an impartial person. Membership in the Knights of Labor grew slowly until Terence V. Powderly, a mechanic from Scranton, Pennsylvania, became its head in 1881. Under Powderly’s leadership, the Knights expanded from 28,000 members in 1880 to about 700,000 in 1886. Although the Knights of Labor declined rapidly after the failure of a series of strikes, other unions continued to organize. Union Movements Diverge Craft Unions and Samuel Gompers: One approach to the organization of labor was craft unionism, which included all skilled workers from many different industries. Under leaders such as Samuel Gompers, the Cigar Makers’ International Union joined with other trade and craft unions in 1886 to form the American Federation of Labor (AFL). With Gompers as its president, the AFL focused on collective bargaining, or group negotiations, to reach written agreements between workers and employers. Unlike the Knights of Labor, the AFL used strikes as a major tactic, rather than as a last resort, to achieve its aims. Successful strikes helped the AFL win higher wages and shorter workweeks for skilled workers. Between 1890 and 1915, the average weekly wages in unionized industries rose from $17.50 to $25, and the average workweek fell from almost 54.5 hours to just under 49. Industrial Unionism and Eugene Debs: Some labor leaders felt that the strength of unions lay in reaching beyond skilled workers to include all laborers- skilled and unskilled- who worked in a specific industry. The concept captured the imagination of Eugene V. Debs, who made the first major attempt to form such an industrial union- the American Railway Union (ARU). Most of the new union’s members were unskilled and semiskilled laborers, but skilled engineers and firemen joined too. In 1894, the new union won a strike for higher wages. Within two months, its membership climbed to 150,000, dwarfing the 90,000 enrolled in the four skilled railroad brotherhoods. Though the ARU, like the Knights of Labor, never recovered from the losses suffered in a major strike, it had its effect. Socialism and the IWW: Eugene Debs and some other labor activists eventually came to believe that eh problems faced by workers were symptoms of an underlying problem with the American capitalist system. They believed that the principles on which the economy was based- private ownership of business and free competition- made the rich richer and the poor poorer. These activists turned to socialism, an economic and political system based on government control of business and property and equal distribution of wealth. Socialism had obvious appeal for the downtrodden workers, whom it would empower. But it threatened the wealthy, whose wealth it would confiscate. Socialism, carried to its extreme form- communism as advocated by the German philosopher Karl Marx- would result in the overthrow of the capitalist system. Most socialists in late-19th-century America drew back from this goal, however, and worked within the labor movement to achieve better conditions for workers. In 1905, a group of radical unions and socialists in the West organized the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), or the Wobblies. Headed by William “Big Bill” Haywood, the Wobblies included miners, lumberers, and cannery and dock workers. Unlike the ARU, the IWWw welcomed women and African Americans, but membership never topped 150,000. Its only major strike victory occurred in 1912. Yet the Wobblies, like the ARU, gave dignity and a sense of solidarity to unskilled workers barred from other groups. Other Labor Activism in the West: Asian and Mexican workers in the West and Southwest also organized unions. In April 1903, about 1,000 Japanese and Mexican workers organized a successful strike in the sugarbeet fields of Ventura County, California. In the wake of their victory, they formed the Sugar Beet and Farm Laborers’ Union of Oxnard. In Wyoming, they State Federation of Labor supported a union of Chinese and Japanese miners who sought the same wages and treatment as other union miners. These small independent unions increased the overall strength of the labor movement and helped fuel the increasing tension between labor and management.