Seven Superstitious Rules of Writing Student

advertisement

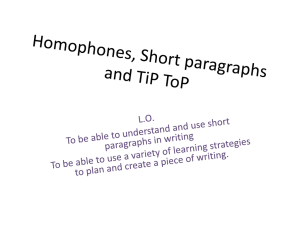

Seven Rules of Writing: Superstitions Excerpted from John Trimble, Writing With Style, 2nd edition, New Jersey: Prentice Hall, 2000. 1. Never begin a sentence with But or And Often taught for three reasons: a) the teachers themselves where taught it at an impressionable age and have never thought to question its legitimacy b) the teachers hope to discourage anything smacking of informality in student writing c) teachers can use this rule as a way to force students to move beyond simple sentences (“The plan is long over due”) to compound ones (“The plan is long overdue, but implementing it will be difficult”). TRUTH: It is absolutely valid to start sentences with And or But. Formal alternatives for And: ___________________________________________________ Formal alternatives for But: ____________________________________________________ CAUTION: begin sentences with And and But sparingly, just because it’s legitimate doesn’t mean it can’t grow tiresome. 2. Never use contractions. There is no real rule against using contractions; you see contractions in all types of professional writing (except maybe scientific articles). TRUTH: It ultimately comes down to nothing more than our taste and values. Examples of contractions:______________________________________________________ ______________________________________________________________________________ CAUTION: Contractions are best used in moderation since it can make your writing seem overly informal. When your ear tells you that the rhythm of a sentence seems to require a contraction, use it. But where a contraction is not required, it’s best not to use one. 3. Never refer to the reader as you. Alternatives: a) never refer to him at all – difficult to do and distances the reader from the writer b) refer to her as “the reader” – depersonalizing and stiff TRUTH: You can use you if it fits with what you’re writing. CAUTION: While you is widely used, it can be overused and is akin to the common phrase “you know” and can become irritating. If you don’t need to say you, don’t. If you do need to, say it without embarrassment exactly as you would in conversation. 4. Never use the first-person pronoun I. Alternatives: Similar to those under Rule #3 a) you practice complete self-effacement and disappear from your prose b) you attempt self-transcendence, in which case you elect to become either an objectification of yourself (the writer) or something more than yourself (we) TRUTH: You can use “I” in most forms of writing. If your assertions are indeed intelligent and well supported, they won’t need props like “it seems to me,” “I think,” and “in my opinion” to go along with it. CAUTION: “Place yourself in the background,” as suggested by Strunk and White in The Elements of Style. Reserve “I” for when you truly need it—either to emphasize that such-andsuch is admittedly just a conjecture or personal prejudice, or to add some humanity to an otherwise dry account. The rest of the time, try to generalize objectively and more or less impersonally, as if you’re pointing out what any intelligent person could see for himself. 5. Never end a sentence with a preposition. TRUTH: It is perfectly acceptable to end sentences with prepositions. Examples of Prepositions: _______________________________________________________ CAUTION: None, it’s an old ‘rule’ carried over from Latin. You can impose it upon yourself if you wish but it’s not necessary. 6. Never split an infinitive. Examples: ____________________________________________________________________ Why most people do it (even if it is unconscious): a) the split infinitive usually sounds better—that is, it has a more idiomatic rhythm to it because we often hear it in common speech. b) it allows the modifying adverb to be positioned where it will receive the most notice, which is directly ahead of the verb. c) since grammarians recommend that modifiers should come, if possible, next to the word they modify, the adverb has as much right to sit next to the verb as the preposition to—and perhaps more right, not only because it is the more weighty of the two words, but because it frequently changes the very sense of the verb. CAUTION: Go by ear and sense. If your ear tells you to split the infinitive, go ahead and do it. If you’re not sure, don’t split it since there’s no pressing reason to. 7. Never write a paragraph containing only a single sentence. Generally this rule is sound. (i.e. writing sentences like “Never.” too frequently is a bad idea) One Exception: Newspapers—The one-sentence paragraph is ideal for this type of writing. It allows reporters to: a) present facts in descending order b) enables a hurried reader to digest facts quickly c) offsets the tedium created by narrow columns and small type Three situations in essay writing where one-sentence paragraphs are appropriate: a) when you want to emphasize a crucial point that might otherwise be buried b) when you want to dramatize a transition from one stage in your argument to the next c) when instinct tells you that your reader is tiring and would appreciate a mental rest CAUTION: The one-sentence paragraph is a great device but don’t over do it. Make sure your sentence is strong enough to withstand the extra attention it’s bound to receive when set off by itself.