Compliance and Foreign Students and Faculty

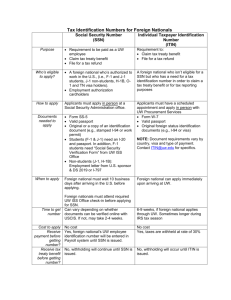

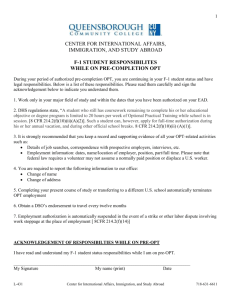

advertisement

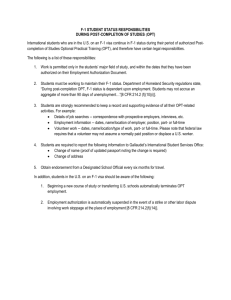

COMPLIANCE AND FOREIGN STUDENTS AND FACULTY April 20, 2007 Leigh Polk Cole, Attorney Dinse, Knapp & McAndrew, P.C. Burlington, Vermont Jane Etish-Andrews Director, International Center Tufts University Boston, Massachusetts Introduction Colleges and universities must comply with U.S. immigration law in enrollment and tracking of international students and scholars and in hiring and employing international faculty. This outline provides an overview of immigration issues and requirements and suggests best practices in several areas. I. Roles of Government Agencies The roles of various state and federal government agencies in the immigration process are a source of confusion. Diverse agencies are involved in immigration regulation. Each government agency has a defined role but their roles overlap in these important respects. U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS). DHS was created in 2003 when large number of government agencies were reorganized into DHS, including the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) (which was a division of the U.S. Department of Justice), Customs, Border Patrol, Coast Guard, the Federal Emergency Management Administration (FEMA), the Secret Service and the Transportation Security Administration (TSA), among others. DHS has overall responsibility for immigration benefits and enforcement. The former responsibilities of INS (benefits, customer service, domestic enforcement and border enforcement) were allocated to various divisions of DHS (USCIS, ICE and CBP, described below). See Exhibit A, DHS Organizational Chart. U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS, in DHS). Formerly the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) under the U.S. Department of Justice, USCIS is a division of DHS with primary responsibility for adjudicating immigration benefits such as applications for immigration status to live, work or study in the United States, applications to change from one status to another, and applications for adjustment of status to permanent residency. USCIS is a National Association of College and University Attorneys 1 benefits and customer service division of DHS. See Exhibit B, I-797 Approval Notice issued by USCIS. U.S. Immigration & Customs Enforcement (ICE, in DHS). ICE is a division of DHS with responsibility for immigration and customs enforcement within the United States (not at the borders). ICE is responsible for the SEVIS system to monitor students and scholars at U.S. institutions of higher education. ICE is an enforcement division of DHS. U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP, in DHS). CBP is a division of DHS with responsibility for enforcement of immigration and customs law at U.S. borders and ports of entry. Travelers requesting entry to the United States are examined by CBP officers. See Exhibit C, I-94 issued by CBP at port of entry U.S. Department of Labor (DOL). The U.S. Department of Labor adjudicates applications for labor certification for permanent residency, maintains a prevailing wage database for all U.S. states, and reviews and approves prevailing wage determinations issued by each state for immigration applications. State departments of labor, employment and training. States agencies are responsible for issuing prevailing wage determinations for immigration applications related to employment in the respective states, based on sources including the prevailing wage database maintained by DOL. U.S. Department of State (State Department or DOS). The State Department and its U.S. consular posts abroad (embassies, consulates) is responsible for issuing U.S. passports to U.S. citizens, issuing U.S. visas to non-U.S. citizens, approving J-1 program sponsors such as institutions of higher education, and approving waivers of the 212(e) 2year home country residency requirement for J-1 exchange visitors. Visa approval involves a security check process. A visa is a permit to request entry to the United States; actual entry is approved by CBP upon a traveler’s arrival at a U.S. port of entry. A visa is not a guaranty that CBP will allow the holder to enter the United States. While many visas are based on an approval issued in advance by USCIS, F-1 and J-1 visas are based on the I-20 or DS-2019 issued by the F-1/J-1 sponsoring institution. See Exhibit D, Visa. II. SEVIS and Immigration Compliance for F-1 Students and J-1 Scholars A. Immigration Status and Benefits for Students and Scholars F-1 Status F-1 status is available for academic study by international undergraduate and graduate students. Institutions of higher education must be authorized by ICE to approve National Association of College and University Attorneys 2 F-1 status for students and to use the SEVIS monitoring system to issue F-1 documentation. See 8 C.F.R. 214.2(f). F-1 status is available only for full time study and only for the period of time needed to complete the degree program up to one year for employment for Optional Practical Training (OPT) after a degree is obtained. J-1 Status J-1 status is available for study, research and cultural exchange, including employment in the United States for these purposes. J-1 program sponsors, including nonprofits, for-profits and institutions of higher education, must be authorized by the State Department to issue J-1 documentation for participants and to use the SEVIS monitoring system to create J-1 documentation. See 8 C.F.R. 214.2(j). The sponsor’s J-1 program, description approved by the State Department, governs which activities are permissible by participants in a J-1 program. Permissible activities include study, research or employment. J-1 status is available for up to 6 years for research scholars and faculty, depending on program requirements. There is no time limitation on J-1 status for full time students. Many J-1 participants become subject to a 2-year home country residency requirement under the Section 212(e) of the U.S. Immigration and Nationality Act. See U.S. Immigration and Nationality Act, Section 212(e), codified at 8 U.SC. 1182(e). Section 212(e) is triggered by U.S. or foreign government funding of the applicant’s program participation or if the field of study or research is on the Skills List for the participant’s home country. The Skills List is a list of occupational subject areas for which J-1 participants are required to return to their home country for at least 2 years to share the information they learned as J-1 exchange visitors in the United States. See 22 C.F.R. 41.63; State Department’s Foreign Affairs Manual (FAM), 9 FAM 41.62, Exhibit II. The 212(e) 2-year home residency requirement must be satisfied or waived before the J-1 participant may obtain any other immigration status in the United States (other than O-1 status based on extraordinary ability in their field of endeavor). 212(e) waivers (or “J-1 waivers”) are difficult obtain and must be based on one of the following, none of which can be assumed to be available in any given case: a. Request by an interested U.S. government agency (IGA) b. Hardship to a U.S. citizen or permanent resident c. A no-objection letter from the participant’s home country. The State Department reviews 212(e) waiver applications and recommends whether a waiver should be approved. Favorable waiver recommendations by the State National Association of College and University Attorneys 3 Department are submitted to USCIS with an I-612 Application for Waiver of the Foreign Residence Requirement, to finalize the waiver process. See 22 C.F.R. 41.63. M-1 Status M-1 status is available for vocational and technical students at approved nonacademic vocational institutions. See 8 C.F.R. 214.2(m). M-1 status is subject to SEVIS monitoring like F-1 and J-1 status. B. History and Purpose of SEVIS SEVIS was conceived before 9/11 as a system to monitor the whereabouts and activities of the vast number of international students and scholars physically present in the United States at any given time. SEVIS was implemented on an expedited basis after 9/11 when it came to light that the 9/11 perpetrators had gained entry to the United States as purported students. SEVIS is a management system for F-1, J-1 and M-1 status only. See 8 C.F.R. 214.12, 214.13. SEVIS is a substantive status system, not merely a database. The information entered into SEVIS by an F-1 or J-1 sponsor, such as an international student advisor at a college or university, becomes the actual government record of the F-1/J-1 student/scholar. If a SEVIS record expires or terminates for any reason, even due to an inadvertent data entry error by the SEVIS officer on campus, the F-1/J-1 student/scholar’s immigration status ends by operation of law and ICE, USCIS and the State Department are notified automatically that the student/scholar is out of status. To maintain lawful F-1 status and a valid SEVIS record, F-1 students must maintain a full course of study, which is defined as a minimum of 12 credit hours per semester or as certified by the college for postgraduate studies. To maintain lawful J-1 status and a valid SEVIS record, J-1 scholars and students must continue to participate in all respects in the J-1 program as described in the approved J-1 program description. The SEVIS system leads to serious immigration issues for F-1s and J-1s as a result of otherwise mundane events in an academic setting, such as: a. Dropping courses below full-time status as defined by the school b. Failure to register on time c. Withdrawal d. Leave of Absence The introduction of SEVIS caused a sea change in campus climate and culture around immigration status for students and scholars. International services staff on National Association of College and University Attorneys 4 campus, who formerly were in the role of advisors and guides for international students and scholars, now play a role in the SEVIS government oversight and enforcement structure for students and scholars. IMPORTANT NOTE: The SEVIS Helpdesk is available to assist SEVIS users with technical issues. But the SEVIS Helpdesk is a computer–oriented helpdesk service staffed by computer-oriented staff who are not immigration examiners. The SEVIS Helpdesk should not be relied upon for immigration compliance information. C. Documentation for F-1 and J-1 Status F-1 sponsoring institutions must apply to ICE for approval as SEVIS users. J-1 sponsoring institutions and the descriptions of each J-1 program must be approved by the State Department. Also, J-1 sponsors must apply to ICE for approval as SEVIS users. F1 and J-1 sponsoring institutions issue immigration documentation created in SEVIS for to F-1 and J-1 participants. These documents are: I-20 for F-1 status, and DS-2019 for J1 status. See 8 C.F.R. 214.2(m); see Exhibit E, I-20; see Exhibit F, DS-2019 (formerly IAP-66, before SEVIS) F-1 and J-1 participants are responsible for obtaining USCIS or State Department approval of their F-1 or J-1 status, based on the I-20 or DS-2019 issued by the sponsoring institution. a. F-1/J-1 participants who are outside the United States must apply for a U.S. visa (F-1 or J-1) at a State Department consular post abroad b. J-1 participants who already are in the United States in another status may apply to USCIS for a change of status to J-1. See Exhibit G, I-797 Approval Notice for Change of Status with Replacement I-94. c. F-1 participants who already are in the United States in another status generally must depart the United States to apply for a U.S. visa (F-1) at a State Department consular post abroad and then return to the United States in F-1 status. USCIS and the State Department consider F-1 status to be a “high fraud” category. Before SEVIS, there was limited monitoring of F-1 students. Unfortunately, F-1 documentation could be obtained improperly on campus and distributed outside the campus community for improper purposes. Also, F-1 status was easily obtained through proper channels by enrollment at a college or university, yet whether the F-1 student undertook bona fide academic activities generally was not necessarily monitored on campus or by the government. For example, 9/11 perpetrators entered the United States in F-1 and M-1 status but were not engaged in bona fide study. For these reasons, intending F-1 students generally are required to go to a State Department consular post for examination and security clearance as part of the visa National Association of College and University Attorneys 5 application process. Changes of status from B-1/B-2 visitor to F-1 are prohibited, unless the applicant already went through the consular process and obtained a B-1/B-2 visitor visa. Applicants for F-1 visas at consular post must establish sufficient ties to their home country to satisfy consular officers that they intend to return. Even if an intending student already is in the United States and a change of status to F-1 is allowed under law, there are important considerations that may weigh in favor of using consular processing to obtain a visa: a. Timing – change of status takes months; b. Financial aid - eligibility may be limited to F-1 students; c. OPT/CPT – eligibility accrues only in F-1 status; and d. Travel – future travel outside the United States will require a visa anyway. D. Studies Permitted by Individuals in Other Lawful Status International students in the United States in other categories lawful status are allowed to study, including H-1B/H-4, TN, L-1/L-2/L-4, TN, 0-1/0-2 and 0-4 status. Students in these status categories are allowed to apply for change of status to F-1 status. Or, perhaps the student can change from B-1/B-2 visitor to one of these other categories for study. Premium processing is available for change of status to H-1B/H-4, L-1/L-2/L4, TN, R, or O status (but not F-1 or J-1) (for a $1,000 USCIS fee for premium processing) which alleviates timing concerns usually related to change of status. Permanent residents (green card holders) also are allowed to study. Dependents of F-1 students in F-2 status are not allowed to study. If F-2 dependents choose to study, they must obtain F-1 status (through change of status or consular application). Study is not permitted for B-1/B-2 visitors, except for short term courses if Visa Waiver applies or a visa is obtained from a consular post for this purpose (example: 15 hours or less per week of English as a Second Language). See Exhibit H, I-94 for B-1/B2 visitor entry with Visa Waiver (WB). SEVIS does not apply to internationals studying in any status other than F-1, J-1 or M-1. International students outside SEVIS may study part-time or in a nondegree programs, as SEVIS compliance requirements do not apply. Campus policies vary regarding study in status categories other than F-1/J-1, and campus tracking varies for international students outside SEVIS. National Association of College and University Attorneys 6 There is no legal duty to track international students outside SEVIS. Nevertheless, there are good policy reasons to track all international students on campus, regardless of their status category: E. a. Travel considerations b. Demographic analysis c. Response to governmental inquiries regarding international community d. Security concerns related to internationals on campus. Consular Adjudication of Visa Applications It is the student’s responsibility to obtain a visa in their passport, with a SEVIS document as supporting documentation (DS-2019 for J-1, I-20 for F-1). See Exhibit D, Visa. A receipt showing payment of the $100 SEVIS fee must be presented at a consular post for F-1, J-1 and M-1 visa applications. See 8 C.F.R. 214.13. Visas are issued only at U.S. consular posts in the applicant’s home country or in Canada or Mexico. Travel and timing concerns raised by this requirement vary according to the student’s or scholar’s home country. Visa terms vary by country according to reciprocity agreements. Depending on reciprocity, a visa may be valid for multiple entries to the United States over 10 years or may be limited to a single entry to the United States within 90 days (this is common for visas issued to citizens of China). F. Employment of F-1 Students F-1 students are permitted to engage in employment on campus or off campus in compliance with specific rules and limits. See 8 C.F.R. 214.2(f)(9). F-2 dependents are not allowed to engage in employment. On Campus. F-1 students may be employed on campus for up to 20 hours per week during the semester and full–time during summers and breaks. An employment authorization document (EAD) is not required for on campus employment. See Exhibit I, Employment Authorization Document (EAD). Off Campus. Optional Practical Training (OPT). F-1 students may be employed off campus for OPT related to the degree program. OPT is available after successful completion of one academic year. The student must be in good academic standing. OPT National Association of College and University Attorneys 7 is valid for an aggregate of 12 months which may be used during the course of study or within 14 months after graduation. OPT eligibility must be endorsed on the I-20 by the international student advisor and the F-1 student must obtain an Employment Authorization Document (EAD) from USCIS before commencing OPT employment. Advance planning is required to obtain an EAD as it can take 3-4 months for EAD applications to be approved by USCIS. Curricular Practical Training (CPT): F-1 students may be employed off campus for CPT that is an integral part of the degree program. CPT eligibility must be endorsed on the I-20. An EAD is not required. There is no limit on the duration of CPT. Twelve months of full-time CPT applies against (eliminates) OPT. Other employment. Other types of employment are possible in special cases such as changed circumstances outside student’s control that qualify as severe economic hardship, but this is very hard to obtain. An EAD is required, and it can take 3-4 months for EAD applications to be approved by USCIS. G. Employment of J-1 Students and Scholars Approved J-1 programs can include employment and to that extent, J-1s are allowed to engage in employment. J-1s are not allowed to engage in any employment that is not part of the approved J-1 program. See 8 C.F.R. 214.2(j). J-2 dependents are allowed to engage in employment in any position for any U.S. employer. 8 CFR 214.2(j)(1)(v)(B). J-2 dependents must obtain an Employment Authorization Document (EAD) from USCIS before engaging in employment. Again, advance planning is required to obtain an EAD – it can take 3-4 months for EAD applications to be approved. IMPORTANT NOTE: To obtain an EAD, J-2 dependents must certify that their employment is optional and is not necessary to support their household. This requirement corresponds to a condition of J-1 status to the effect that the J-1 applicant must have adequate financial support for the entire household without considering any income that may be derived by J-2 dependents through employment in the United States. J-1 students can qualify for up to 18 months of employment for academic training (AT) during their studies or following completion of their studies. J-1 students completing their PhD can qualify for up to 36 months of AT if they are pursuing a post doctoral training program. No EAD is required for AT. AT eligibility is authorized by the international student advisor’s endorsement on the J-1 student’s DS-2019. III. Immigration Compliance for Faculty Immigration for faculty utilizes employment-based categories such as H-1B, TN, O and permanent residency, and J-1 status if the J-1 program allows teaching. The National Association of College and University Attorneys 8 typical scenario for tenure-track faculty involves H-1B status followed by permanent residency. A. H-1B Status for Specialty Occupation Workers H-1B is a temporary status available for a maximum of 6 years. Occupations qualify for H-1B status if a bachelor’s degree or equivalent specific vocational preparation is a minimum requirement for entry into the profession. See 8 C.F.R. 214.2(h)(1)(ii)(B). USCIS relies on the resources maintained by the U.S. Department of Labor (not the particular requirements of a particular employer) to determine whether an occupation requires a bachelor’s degree or equivalent as a minimum qualification. College and university faculty positions are eligible for H-1B status, as are IT staff, librarians, residence life professionals, health educators, and many other professionals on campus. There are important regulatory requirements for H-1B petitions, including: a. Labor condition approval is required from the U.S. Department of Labor. See 8 C.F.R. 214.2(h)(1)(ii)(B)(1). b. The employer must pay the prevailing wage as determined by the U.S. Department of Labor. c. The employer must post a notice with specific information about the proposed H-1B position, including the offered wage, for ten days in two locations at the place of work.. d. The employer must maintain a public access file for 4 years after the application is filed (or for a shorter time, if the H-1B employment terminates in less than 4 years) which documents the basis for the H-1B petition and is available to the public upon request. e. The employer must make specific attestations about the state of the labor market and certify that employing an H-1B worker will not displace U.S. workers. See 22 C.F.R. Part 655. One well publicized challenge related to H-1B status is that the number of H-1B approvals is limited to 65,000 each year (the so-called “H-1B cap”) plus 20,000 additional approvals for beneficiaries holding at least a masters degree from a U.S. institution. IMPORTANT NOTE: Colleges and universities, and affiliated nonprofits, are exempt from the H-1B cap, so the H-1B cap is not an issue for college and university employers. H-1B approvals take about 5 months at USCIS, which presents a challenge for employers seeking to start a new employee within the customary 2 to 4 weeks after hire. National Association of College and University Attorneys 9 Premium processing is available for H-1B petitions, but it costs an additional $1,000 USCIS filing fee. With premium processing, an H-1B approval can be obtained in 2 to 6 weeks (6 weeks if USCIS issues a request for evidence and the employer responds immediately). There are other costs associated with H-1B petitions, including filing fees of approximately $690 (subject to change), staff time to prepare the application, and document preparation fees (in-house) or attorneys fees to prepare the application and handle compliance steps, all of which can cost an additional $1,500 to $2,500. IMPORTANT NOTE: There are additional USCIS filing fees for H-1B petitions of $750 or $1,500 for most H-1B employers but colleges and universities are exempt from all but $690 of the H-1B filing fees. Campus policies vary on H-1B sponsorship and use of in-house staff or outside counsel. Some campuses routinely use H-1B status for all types of eligible staff, and others limit sponsorship to positions that require advanced degrees or tenure track faculty. B. O Status for Extraordinary Ability O status is a temporary status for workers who have risen to the top of their fields of endeavor. O status is available for an initial period of three years and then can be renewed every year indefinitely, but eligibility must be proven anew at each renewal. A petition for O status requires extensive documentation that the beneficiary is one of a small percentage who has risen to the top of the field of endeavor, based on statutory criteria such as awards, original scientific contributions, publications by the beneficiary, publications by others extolling the importance of the beneficiary’s work, established role as a peer reviewer for others in the field, and high compensation relative to others in the field. See 8 C.F.R. 214.2(o). Eligibility for O status is difficult to establish and requires a high standard of proof. There are no labor condition, labor certification or prevailing wage requirements for status. Nevertheless, there are significant timing and cost considerations. Approval of an O petition takes approximately 5 months under normal processing at USCIS. Premium processing is available (with an $1,000 USCIS filing fee for premium processing). Most importantly, it takes a significant amount of time and effort to assemble the required documentation for a successful O petition, and document preparation fees (in-house) or attorneys fees can be substantial ($2,000 to $5,000 is not unusual). C. TN Status for Canadians under NAFTA TN is a temporary status available under the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) for citizens of Canada and Mexico in certain professions listed in NAFTA, including college and university teachers. See North American Free Trade Agreement, Annex 1603, Section D; 8 C.F.R. 214.2(b)(4). For Canadians, TN status can National Association of College and University Attorneys 10 be obtained at a U.S. port of entry upon presentation of a letter from the employer establishing a qualifying offer of employment along with documentation that the employee meets the qualifications for the position (degrees or certificates and applicable licenses). IMPORTANT NOTE: TN status is not available for clinical physicians, so it is of limited utility for faculty at academic medical centers (H-1B is useful for those cases). TN approvals are issued for only one year, renewable each year The process for obtaining TN approvals for citizens of Mexico is less favorable than for citizens of Canada, and port of entry adjudication is not available. It generally makes more sense to apply for H-1B status for a citizen of Mexico, to avoid renewing TN status every year. If necessary, a citizen of Mexico can change from H-1B status to TN status after using all 6 years of H-1B status if permanent residency was not obtained during the H-1B employment. D. Permanent Residency, Labor Certification Permanent residents hold a “green card”. Permanent residents can live and work in the United States indefinitely. See Exhibit J, I-551 Alien Registration Card (“green card”). To support an employment-based permanent residency petition, the employment must be full-time and permanent, meaning a position that exists permanently in the hiring department and is not subject to grant renewals. Labor certification is required for most permanent residency cases. See 20 C.F.R. Part 656. Labor certification is obtained from the U.S. Department of Labor through an automated application process (known as PERM). See 20 C.F.R. 656.17. Machinereadable PERM applications are subject to audit of the underlying compliance documentation by the U.S. Department of Labor. See 20 C.F.R. 656.20. Employers are required to create and maintain a complete file of supporting documentation for every PERM case. To obtain labor certification, the employer must pay the prevailing wage requirement as determined by the state labor department and approved by the U.S. Department of Labor. The employer also must test the labor market within 6 months before filing the labor certification application to establish there is no minimally qualified U.S. applicant ready and willing to take the job. The test of the labor market for PERM labor certification applications must meet detailed requirements, including: a. Newspaper advertisement in print (two Sundays) b. A print journal advertisement can take the place of one Sunday newspaper advertisement for professional positions National Association of College and University Attorneys 11 c. Position must be posted on employer web site if that is customary d. Three other recruitment steps are required (such as local or ethnic newspaper, job search web site, job fair, employment service or recruiter). See 20 C.F.R. 656.17. IMPORTANT NOTE: PERM does not allow employer to rely upon electronic advertising in lieu of print advertisements in newspapers or journals. Sponsorship for permanent residency is employer-specific, but once it is approved the permanent resident is not tied to sponsoring employer. This is a significant consideration for employers who want to retain sponsored employees long-term. The sponsored employee can leave the sponsoring employer at a specific point during the application process (180 days after filing of I-485 adjustment application) or anytime after approval, and can take other employment in the same occupational classification without losing the benefits of the sponsoring employer’s immigrant petition. Also, beginning at a specific point during the application process (upon issuance of an Employment Authorization Document or EAD), the employee can work for any other U.S. employer in addition to the sponsoring employer (“moonlighting”) without jeopardizing the permanent residency sponsorship. D. Special Handling Labor Certification for Teaching Faculty Good news! There is a more favorable labor certification process for college and university classroom teachers only. Colleges and universities can sponsor faculty for permanent residency and rely on a competitive recruitment conducted in the past (the recruitment can be more than six months old). See 20 C.F.R. 656.18. Under so-called “Special Handling Labor Certification” for college and university teachers, colleges and universities also can select the “most qualified” candidate for a faculty position, rather than showing there is no minimally qualified U.S. candidate. To qualify for Special Handling Labor Certification, the college or university must file the labor certification application within 18 months after the teacher was “selected”, to be eligible to obtain labor certification based on the prior competitive recruitment. Otherwise, the college or university must test the labor market again with a competitive recruitment that meets the employer’s usual standards (not a full blown PERM recruitment) within 6 months before a labor certification application is filed. E. Current Challenges in Permanent Residency Application Process: Visa retrogression See Exhibit K, Visa Bulletin for April 2007 (issued monthly by State Department). National Association of College and University Attorneys 12 “Visa retrogression” refers to a lack of availability of visas under numerical limits imposed under U.S. immigration law. In other words, the visas in certain categories have run out and are not available until a future date. If a visa category is subject to retrogression, the employer can file the I-140 Petition for Immigrant Worker, and the I-140 Petition can be approved, but the beneficiary/employee cannot file an I-485 Application for Adjustment of Status until a visa is immediately available for the case. Whether a visa category is retrogressed, and if so, at what future date a visa will become available, varies by country of birth because numerical limits on U.S. visas vary by country of birth. To navigate visa retrogression, look for the visa preference category for which a visa is immediately available and the applicant is most readily eligible. Employmentbased preferences 1, 2 and 3 (EB-1, EB-2 and EB-3) are the most commonly used by colleges and universities. See U.S. Immigration and Nationality Act, Section 203(b) (13), codified at 8 U.S.C. 1153(b)(1-3). a. EB-3: Employment Based Third Preference –Skilled Workers, Professional and Others (retrogression applies to all applicants as of April 2007; see chart in Visa Bulletin, Exhibit K) i. ii. iii. iv. Labor certification required Skilled workers – 2 years of training or experience Professionals – BA or equivalent required Other workers – less than 2 years of training or experience OR, if not: b. EB-2: Employment Based Second Preference (EB-2) (retrogression applies to citizens of India and China as of April 2007; see chart in Visa Bulletin, Exhibit K) i. Labor Certification required (including special handling labor certification for college and university classroom teachers) ii. Advanced Degree Professionals (MA or BA plus 5 yrs of progressive experience) iii. Workers of Exceptional Ability (3 of 6 statutory criteria) OR, if not: c. EB-1: Employment Based First Preference – Priority Workers (no retrogression as of April 2007; see chart in Visa Bulletin, Exhibit K) National Association of College and University Attorneys 13 i. No labor certification required but requires extensive documentation of eligibility. ii. Workers of extraordinary ability (similar to O-1 standard, discussed above, but subject to a more stringent standard of proof) iii. Outstanding professors and researchers (3 years plus 2 of 6 statutory criteria) There are other employment based visa categories for clergy, investors, Iraqi and Afghani translators and for employment in designated high unemployment areas, but these categories are not commonly used by colleges and universities. See chart in Visa Bulletin, Exhibit K. Security Checks All immigrant applications at USCIS and all visa applications at State Department consular posts now are subject to security checks, which can take time. Delays can be substantial (weeks or months in some cases), especially for countries subject to the National Security Entry-Exit Registration System (NSEERS): Afghanistan, Algeria, Bangladesh, Bahrain, Egypt, Eritrea, Indonesia, Iran, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Libya, Morocco, North Korea, Oman, Pakistan, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, Tunisia, United Arab Emirates and Yemen. The time required for security checks, and the relative risk of a long security check for a particular applicant, is a significant consideration in planning travel, visa applications at consular posts abroad, and potential timing for permanent residency applications. IMPORTANT NOTE: When a visa applicant applies for a visa at a U.S. consular post, the applicant cannot return to the United States until the visa is approve, even in the applicant has another approved U.S. immigration status and travel documentation. See State Department’s Foreign Affairs Manual (FAM), 9 FAM 41.112, Notes 4.2 , 4.3. The risk of a visa delay due to security clearance is a significant concern when making travel plans and weighing the advisability of travel outside the United States that will require a visa application at a U.S. consular post abroad. IV. Volunteering The ability of internationals to “volunteer” in the United States is a common topic of discussion. Internationals only are allowed to provide volunteer services in roles that typically are provided by volunteers and for which U.S. workers are not paid. For example, if U.S. volunteers commonly read childrens books aloud at a library story hour, an international can read childrens books aloud at the library story hour. However, if other people are paid for the services, an international cannot provide the services as a “volunteer.” For example, librarians usually are paid and therefore internationals cannot “volunteer” as a librarian. U.S. immigration law and employment law protect all workers (U.S. citizens and internationals) from being exploited by working for no pay or for National Association of College and University Attorneys 14 wages that are below the minimum wage. Employers who allow internationals to “volunteer” in a position for which U.S. workers are paid risk both a wage and hour violation under state law and an immigration violation under federal law. V. Social Security Numbers Under current U.S. Social Security Administration polices and practices, social security numbers (SSNs) only are available to U.S. citizens and internationals who are authorized for employment. Students are not eligible for SSNs unless they are employed or have an EAD for OPT. Students do not need an SSN to open a bank account, as banks can open an account based on the student’s passport rather than an SSN. Employees can start work while an application for an SSN is pending. Employees must apply for an SSN within 3 days after commencing employment. While the SSN application is pending, the employer can enter a fictional (dummy) social security number as a placeholder in the payroll system. When the actual social security number is issued, the employer replaces the dummy number with the actual number. The actual social security number must be used for year end reporting. VI. Selected Best Practices and Policies I-9 Processes Each campus should have one office preparing I-9s in a centralized manner, with trained staff familiar enough with immigration requirements to identify issues. Immigration issues can be discovered when the I-9 is completed, which is the express purpose of the I-9 process. Immigration problems that should be discovered when an I-9 is completed may go unnoticed until later (and become a larger problem) if the I-9 officer is not familiar with immigration requirements. Good lines of communication should be established between the I-9 officer and the international office to identify and resolve immigration issues efficiently and effectively. Respect for Campus Culture Variations among immigration policies and practices at individual campuses flow naturally from varying approaches and circumstances at each institution. To foster understanding and predictability and to enhance leadership support at all levels, immigration policies and practices should be in line with campus culture, not more strict or more permissive than the institutional environment in general. Institutional Representation for Immigration National Association of College and University Attorneys 15 If an immigration application is employment-based, the employer is the petitioner and the immigration attorney is deemed to represent the sponsoring institution/employer. If the immigration attorney is selected and paid by the employee, the institution needs to monitor institutional compliance with immigration laws throughout the process. Campus Structure Immigration Services The administrative structure responsible for immigration compliance on campus varies widely among campuses. There are advantages and disadvantages of various structures for immigration services: a. All immigration can be part of Human Resources, General Counsel, Student Affairs or Academic Affairs; b. Immigration for faculty, staff and students can be part of different offices, for example: i. Faculty immigration as part of Academic Affairs; ii. Student immigration as part of Student Affairs; and iii. Staff immigration as part of Human Resources; or c. Immigration can be combined with all other International issues (study abroad, international campus locations) under Academic Affairs; or d. Immigration functions can be housed in other structures that make sense on a particular campus. Campus Working Group for Immigration Services The college or university’s International Services Advisor, General Counsel, and Immigration Counsel, and either Human Resources (for employee immigration) or Student Affairs (for student immigration) each have an important role in immigration matters, particularly in setting policy and dealing with problem cases. To foster efficiency, legal compliance and institutional harmony, each campus should identify an immigration team including representatives of each of these campus constituents, to guide or set immigration policy and handle problem immigration cases. National Association of College and University Attorneys 16 EXHIBITS A DHS Organizational Chart B I-797 Approval Notice issued by USCIS C I-94 issued by CBP at Port of Entry D Visa E I-20 F DS-2019 G I-797 Approval Notice for Change of Status with Replacement I-94 H I-94 for B-1/B-2 Visitor Entry with Visa Waiver (WB) I Employment Authorization Document (EAD) J I-551 Alien Registration Card (green card) K Visa Bulletin for April 2007 National Association of College and University Attorneys 17 Exhibit A National Association of College and University Attorneys 18 Exhibit B I-797 Approval Notice issued by USCIS National Association of College and University Attorneys 19 Exhibit C I-94 Issued by CBP at Port of Entry National Association of College and University Attorneys 20 Exhibit D U.S. Visa National Association of College and University Attorneys 21 Exhibit E I-20 National Association of College and University Attorneys 22 Exhibit F DS-2019 National Association of College and University Attorneys 23 Exhibit G I-797 Approval Notice for Change of Status with Replacement I-94 National Association of College and University Attorneys 24 Exhibit H I-94 for B-1/B-2 Visitor Entry with Visa Waiver (WB) National Association of College and University Attorneys 25 Exhibit I Employment Authorization Document (EAD) National Association of College and University Attorneys 26 Exhibit J I-551 Alien Registration Card (Green Card) National Association of College and University Attorneys 27 Exhibit K Visa Bulletin for April 2007 National Association of College and University Attorneys 28 National Association of College and University Attorneys 29 National Association of College and University Attorneys 30 National Association of College and University Attorneys 31 National Association of College and University Attorneys 32 National Association of College and University Attorneys 33