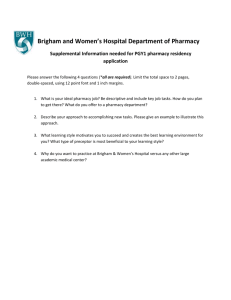

The Changing Context of Pharmacy Leadership

advertisement