Business Times - 23 Aug 2006

Beijing needs to fix cracks in banking

Reforms must deal with corporate governance, internal controls and risk management

issues

By FRIEDRICH WU

CRACKS in China's banking sector predated the 1997-98 Asian financial crisis and originated

from the 'bubble' years in the mid-1990s when state-owned banks and enterprises fed on each

other with an explosive investment-and-lending binge.

As an economic boom slid into a bust, many of the bank loans inevitably turned sour. At its peak

in 1998-99, the average ratio of non-performing loans (NPL) in China's banking sector

skyrocketed to exceed 50 per cent - on par with Indonesia's in the midst of the Asian financial

crisis.

Since then, the Chinese government has taken a few steps to clean up banks' balance sheets by

creating the China Banking Regulatory Commission (CBRC) as a supervisory watchdog and

establishing several asset-management companies to take over bad loans from banks. These

efforts have yielded some visible results.

According to estimates by the international credit rating agency, Standard & Poor's, sector-wide

NPL ratio had fallen from the peak of over 50 per cent to around 21-25 per cent at the end of

2005. However, this is still considered unacceptably high by international standards.

Furthermore, the clean-up has been extremely costly to the government. Between 1998 and 2004,

it has been estimated that 3.57 trillion yuan (US$677 billion) had been spent to recapitalise or

close ailing financial institutions, a gargantuan sum equivalent to 22.3 per cent of the country's

2004 GDP.

Needless to say, such high expenditure has an adverse effect on the government's public finance.

This is reflected by a steady rise in the government's domestic debt. As a percentage of GDP,

public-sector debt increased from 15.5 per cent in 1999 to an estimated 20.7 per cent in 2005.

CAR deadline

To stem further deterioration in the quality of bank assets, CBRC has set end-December 2006 as

the deadline for banks to comply with the Bank for International Settlements' (BIS) guideline for

capital-adequacy-ratio (CAR) of 8.0 per cent. However, as the still high NPL ratio requires banks

to make substantial provisions for problem loans, many banks are highly unlikely to be able to

meet the deadline.

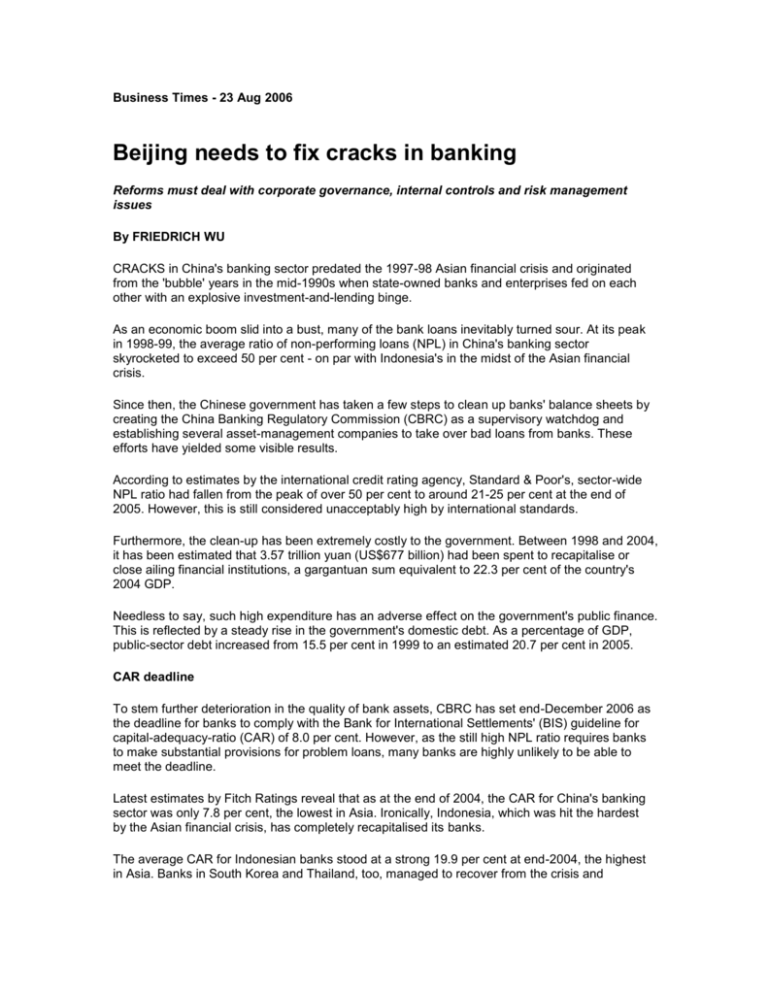

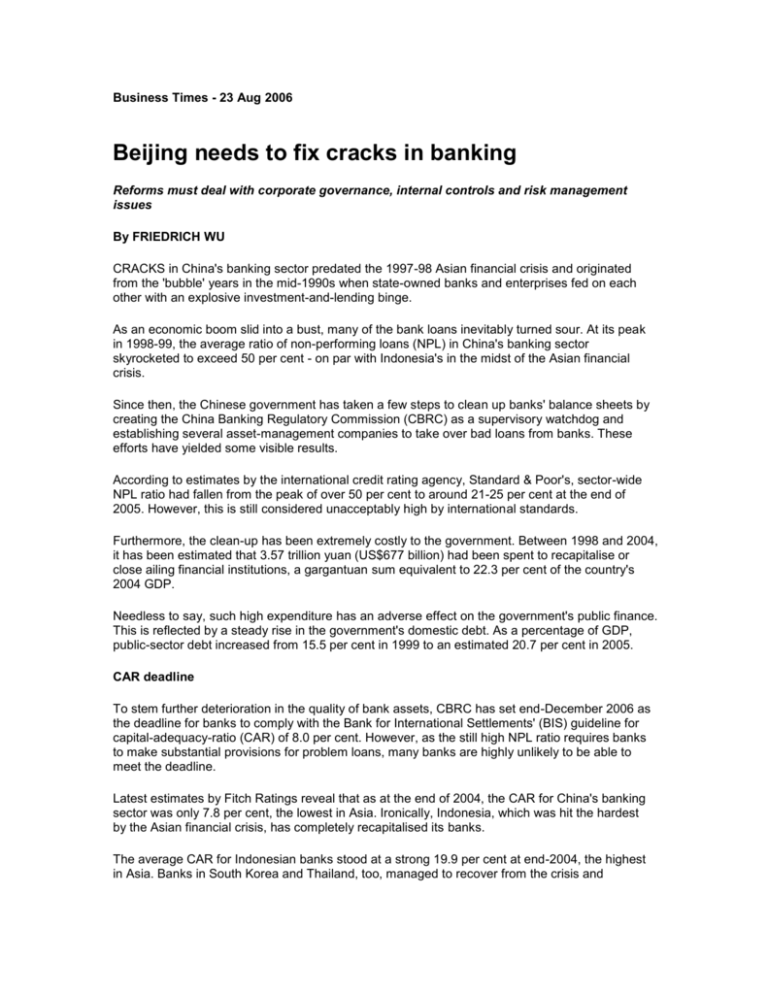

Latest estimates by Fitch Ratings reveal that as at the end of 2004, the CAR for China's banking

sector was only 7.8 per cent, the lowest in Asia. Ironically, Indonesia, which was hit the hardest

by the Asian financial crisis, has completely recapitalised its banks.

The average CAR for Indonesian banks stood at a strong 19.9 per cent at end-2004, the highest

in Asia. Banks in South Korea and Thailand, too, managed to recover from the crisis and

achieved high average CARs of 12.2 per cent and 12.7 per cent respectively. Meanwhile,

Chinese banks seem still a long way from complying with this international yardstick.

According to the government publication Beijing Review, 'only 25 of China's 130 banking

corporations currently meet the standard in terms of capital adequacy ratio'. Failure to measure

up to the BIS-CAR guideline means that, vis-a-vis their Asian counterparts, bank assets in China

will be more exposed to credit risk which over time could lead to another rising tide of new NPLs.

Critical task

In fact, this was one of IMF's key concerns when it performed its annual diagnosis of the Chinese

economy last year. In the released document, it emphatically urged that 'the critical task for the

CBRC will be to see that all banks are taking the necessary steps to ensure that they can comply

with capital adequacy requirements with full provisioning by (the beginning of) 2007'.

It also cautioned that 'with banks heavily involved in lending to sectors facing future overcapacity

- credit risk in the banking sector is likely to remain high', and hence 'more efforts are needed to

restrain the rate of new NPL creation'.

To attach some realism to its warning, IMF projected that '16 per cent of new loans will eventually

become nonperforming'. This prediction is not too far-fetched especially in the current climate of

economic 'over-heating' fuelled by investment and lending booms.

Nevertheless, concentrating mainly on cleaning up existing problem loans and stanching the flow

of new ones is a treatment only for the symptom rather than for the root causes of the malaise in

China's banking sector - which are poor corporate governance, ineffectual internal controls, and a

weak credit-risk-management culture.

In a recent study by McKinsey & Company, its consultants point out that '(m)any Chinese banks

lack even the most fundamental components of good corporate governance', and they further

single out 'poor credit-risk-management skills' as a 'core issue' in CBRC's on-going efforts to

overhaul Chinese banks.

Not only have these deficiencies contributed to bad lending practices (hence resulting in NPLs),

in combination they have also spawned persistently high incidents of fraud. In 2005 alone, for

instance, CBRC managed to unearth irregularities involving misused funds of 767.1 billion yuan.

Even though, in connection to these misused funds, CBRC was able to uncover 1,272 criminal

cases and discipline 6,826 banking staff (including 325 senior managers), only 1.47 billion yuan

or 0.19 per cent, could be recouped. What is really startling is that these are statistics for just one

year.

One can therefore imagine how, year after year, the cumulative corrosive effect of these

malpractices has wrecked China's banking system.

In the past two years, Chinese regulators have attempted to hasten and deepen the banking

reform process by letting foreign banks acquire stakes of up to 25 per cent ownership of their

Chinese counterparts on a highly selective basis.

This is a step in the right direction, as foreign banks would bring in not only fresh capital, but also

cutting-edge expertise, technologies and business models to help modernise China's antiquated

banks.

On the other hand, as minority shareholders, foreign banks' influence at the board-of-directors

level, and hence on the corporate governance issue, is likely to be rather limited.

To lift the latter's standard, strong political will is required on the part of government regulators.

While no one would suggest that China's banking sector is on the brink of collapse, letting the

problems fester would increase both the risk of a large systemic financial crisis and future bail-out

costs.

Until the Chinese government makes a total and unwavering commitment to accelerate the

disposal of existing bad loans, to prevent the flow of new ones, and, ultimately, to build a stronger

banking system through better governance and risk management, banks will continue to be a

drag on the economy.

The writer is Adjunct Associate Professor at the Institute of Defense & Strategic Studies,

Nanyang Technological University and a Senior Research Associate at East Asian Institute,

National University of Singapore

Copyright © 2005 Singapore Press Holdings Ltd. All rights reserved.