The Artist as Witness: Zainul Abedin and the Bengal Famine of 1943

advertisement

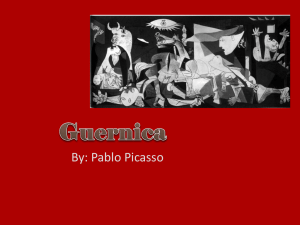

The Artist as Witness: Zainul Abedin and the Bengal Famine of 1943 James Lewis December 2008 www.livingwithflooding.eu The Bengal Famine of 1943 is said to have caused the deaths of possibly 4 million people. At that time, Bengal continued to be ruled by the British colonial government of India, being divided in 1971 by the Partition and the creation of Bangladesh. In 1943, during World War Two, Japan had occupied most south-east Asian countries, including Burma, it being anticipated that Bengal would be next to fall. In preparation for possible enemy occupation, the government removed Bengal rice stocks, destroyed country boats - the most common means of transport in rural Bengal - and a large number of steamers and trains were removed further west to further paralyse river communications. All of these actions seriously hampered food supply but also, inflation, rising prices and hoarding of necessary commodities conspired to bring about famine1. Inured as we are to the statistics of disaster, what do these notes from history mean as we read them now, and how do we comprehend the scale and impact of human suffering then and of imminent recurrence? Sixty-five years after the Bengal Famine, Bangladesh is reported as being one of 7 countries in which 65% of their total population is unable to access a daily minimum of food.2 What is it like to die of hunger, or to drown or to be crushed to death, or to lose a child or one’s family? Where is the emotion in what we read and see in our media; where is the emotion in analyses of events of which we have the data but remain detached from experience of them - without which our understanding is remote? We may tell ourselves that emotion is a subjective matter where we are constrained to objective “evidence” for academic conclusion and achievement; but can it be justifiable for reason to be separated from emotion, suggested, as it has been, as being essential to rational thinking and crucial to human intelligence and humanity.3 It may not be often that the artists’ work is used as evidence but it has its place, especially where information of other kinds is difficult to find, or to which access is obstructed or difficult to achieve or to reach. Henry Moore’s 1941 drawings of people sheltering in the London Underground during the blitz are one example, a Bahamian artist’s drawings of young chickens impaled on wire fences conveyed better than many other sources the power of hurricane wind, and an analysis of sea flooding at Chiswell, Dorset used an artist’s work as partial evidence of coastal activity in history.4 The work of artists transcends detachment and is more readily comprehensible as a human response to the suffering of fellow humans. And without a camera to be behind, an artist transiently participates with his/her subject for longer, usually, than does a news photographer and can convey more than the picture. Pablo Picasso’s painting “Guernica” was made after the April 1937 bombing of the town of that name at the start of the Spanish Civil War: “As the painting developed, it was possible to watch the balance that Picasso kept between the misery caused by war, seen in the anguish of the women, the pain of the wounded horse or the pitiful remains of the dead warrior; and the defiant hope of an ultimate victory.” His series of preliminary pencil studies, however and one in particular simply numbered “(5)” and dated “1er Mai 1937”5, convey passion and anger even more than does the finished painting. There is no record of Picasso having visited Guernica, either before or after the bombing, his anger at the event being the driving force for his work.6 In contrast, Zainul Abedin did visit Calcutta in 1943 for his series of drawings of street people suffering the effects of the Bengal Famine. Made in Calcutta where “humanity was at its most ignominious condition competing with dogs in their hunt for a meal out of the garbage tins on the pavements...a case of terrible human exploitation and degradation”, Abedin’s drawings, for which he was dubbed “an artist of the downtrodden”, have become a unique archive of an event for which records of other kinds may not have been as publicly accessible. Made in black ink with a brush on wrapping paper or cardboard “he recorded tragic scenes with a documentary objectivity and an artistic power (in which) there is a spontaneity, sincerity and an uncompromising realism...”.7 More than media images, more than written description, more than oral account, more than art as a therapeutic medium for survivors, and more than pictorial representation of an experience long passed, the contribution of artists in the event has the power to outclass and to outlast many other sources of record. To despatch artists to scenes of disaster could powerfully assist understanding of vulnerability as a cause of famine, recurrent and by the same causes year by year and generation by generation without change, in spite of our analysis and polemic, as landless families and those headed by women now are again identified as the most vulnerable to inadequate food consumption and possible famine again. If artists can be commissioned in war, why not in disasters of all kinds? Illustrations are taken from Islam Muhammad Sirajul (Ed 1977), see note 7 below. . NOTES 1 Islam, Sirajul (Ed) 1992 History of Bangladesh 1704-1971 Political History Dhaka The Asiatic Society of Bangladesh. 2 UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (2008) Food crisis could worsen, warns FAO IRIN Humanitarian news and analysis 9 December http://www.irinnews.org/Report.aspx?ReportId=81892 and Borger, Julian (2008) Nearly a billion people worldwide are starving UN agency warns The Guardian 10 December http://www.guardian.co.uk/world/2008/dec/10/hunger-population-un-food-environment 3 Damasio, Antonio (2006) Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason and the Human Brain Vintage. 4 Lewis, James (1979 ) Vulnerability to a natural hazard: Geomorphic, technological and social change at Chiswell, Dorset Natural Hazards Research Working Papers 37. University of Colorado and Case Study V pp109-123 in Lewis, James (1999) Development in Disaster-prone Places: Studies of Vulnerability IT Publications (Practical Action). London. Lithographic print in the author’s possession. 5 6 7 Penrose, Roland (1981) Picasso: His Life and Work Granada. pp295-324. Quotation p303. For Guernica see http://records.viu.ca/~lanes/english/hemngway/picasso/guernica.htm Islam, Muhammad Sirajul (Ed 1977) Zainul Abedin Art of Bangladesh Series 1. Dhaka. The Bangladesh Shilpakala Academy. The publication contains 23 images made in Calcutta of the Bengal Famine; these and other work by Zainul Abedin are exhibited at the Bangladesh National Art Gallery and at the Shilpakala Academy in Dhaka.