Br, Joche-Albert Ly

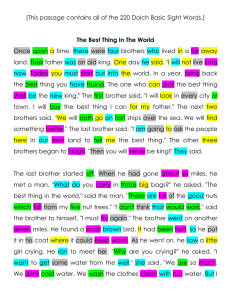

advertisement