Report on Childhood Obesity

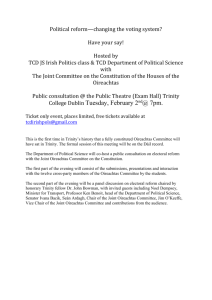

advertisement

An Comhchoiste um Shláinte agus Leanaí Tuarascáil ar Otracht i measc na hÓige Meitheamh 2014 Joint Committee on Health and Children Report on Childhood Obesity June 2014 31/HHCN/015 31st Dáil Members of Joint Committee on Health and Children DEPUTIES Jerry Buttimer TD CHAIRMAN (Fine Gael) Clare Daly TD (Independent) Catherine Byrne TD (Fine Gael) Regina Doherty TD (Fine Gael) Ciara Conway TD VICE CHAIR (Labour) Robert Dowds TD (Labour) Peter Fitzpatrick TD (Fine Gael) Seamus Healy TD (Independent - WUAG) Billy Kelleher TD (Fianna Fáil) Eamonn Maloney TD (Labour) Sandra McLellan Sinn Féin Mary Mitchell O’Connor TD (Fine Gael) Dan Neville TD (Fine Gael) Caoimhghín Ó Caoláin TD (Sinn Féin) Robert Troy TD (Fianna Fáil) Senators Senator Colm Burke (Fine Gael) Senator John Crown (Independent) Senator John Gilroy (Labour) Senator Imelda Henry (Fine Gael) Senator Marc MacSharry (Fianna Fáil) Senator Jillian Van Turnhout (Independent) Table of Contents SECTION 1 RAPPORTEURS’S REPORT ...................................................................................................... 1 SECTION 2 LIST OF THOSE WHO PRESENTED TO THE COMMITTEE............................................................. 27 SECTION 3 ORAL PRESENATATIONS ...................................................................................................... 29 SECTION 4 TRANSCRIPTS OF MEETINGS ............................................................................................... 31 SECTION 5 TERMS OF REFERENCE ........................................................................................................ 33 Foreword by the Joint Committee on Health and Children Report Rapporteur, Peter Fitzpatrick, T.D. I am very grateful to my colleagues on the Joint Committee for nominating me as Rapporteur in relation to this very important topic and in supporting me in bringing this report to publication. The Joint Committee identified this issue as one that has systemic, ongoing and serious implications for the health of the nation going forward and is delighted to have this opportunity to contribute to public debate and Government policy. The Joint Committee recognise that much has been written in recent years about the longterm dangers of childhood obesity. We all know the underlying causes; sedentary lifestyle, poor diet and lack of education. However, the solution is not so easily defined and what I, and the Joint Committee, have attempted to do in this report is to present and analyse the views of some important stakeholders with whom we met. Among the many sectors represented before the Joint Committee in 2012/13 were food production, health, and sports and fitness. Each and every one has made valuable points and greatly enhanced the debate. Their co-operation and insight have allowed the members of the Joint Committee to become better informed and to reflect on and identify the key issues involved. In addition, I have tried, in this report, to bring my own experience to bear on what we heard from those stakeholders and in a brief review of research in this area. In relation to that personal experience which I hope is reflected in the Joint Committee’s report is my lifelong involvement in sport and particularly Gaelic Football. I have been lucky enough to meet and be guided by people who could see that participation in sport has huge 1 benefits not only for the individual but also for the community. I have seen at first-hand how young people who didn’t necessarily do well at school were helped in life by their participation in sport, not only with regard to the lessons to be learned from team work, commitment, loyalty and selflessness but also from the friendships and contacts they made along the way. This can be summed up as showing them that exercise and participative sport in particular can give them an opportunity to be part of something positive that is bigger than themselves. It is generally acknowledged that the recommendations of the National Task Force Report on Obesity 20051 have either not been implemented or have not had the desired effect on the rise of obesity in Ireland. In this report Chairman John Treacy used the phrase “Joined up thinking”. I believe that John was absolutely correct that this concept was essential in any Government strategy, especially one addressing this policy area. One of the elements of dealing with a complex and multi-faceted problem like the obesity epidemic is a willing and co-ordinated response by Government at both the political level and from Government Departments. This response should be imaginative, forward thinking and courageous. We need Ministerial consensus with regard to the fact that whatever strategies are agreed must be implemented regardless of the short term cost, because the future cost of failure will be both high and, potentially, unsustainable. I believe that a positive and co-ordinated strategy must try to maximise, not only the impact of the primary objective, but try to bring about positive social and economic changes that will have an on-going positive influence in the areas of public health, participation in sport, stimulating economic activity and creating sustainable employment The Joint Committee and I hope therefore that, through this report’s highlighting of key issues, we can help to contribute to healthier lives for our young people. This is our objective. Together, we now entrust this work to the Government and, in the first instance to the Ministers for Health and Children and ask them to co-operate with their colleagues to ensure that all the relevant Departments address the key issues identified within the report. 1 Available online at: http://www.dohc.ie/news/2005/obesity.html 2 Report on Childhood Obesity Contents Key issues ............................................................................................................................. 4 Education and public awareness .................................................................................... 4 Young entrepreneurs...................................................................................................... 5 Ireland’s food and retail industry ..................................................................................... 5 1. Prevention is better than cure – the context to childhood obesity ...................................... 6 1.1 The importance of breast-feeding as an early intervention measure ............................ 6 2. Children and the excessive consumption of Junk Food ..................................................... 8 3. The problems facing teenagers ......................................................................................... 8 4. Obesity and mental well being ........................................................................................... 9 5. Publicly-funded Junk Food ................................................................................................ 9 6. Food Heroes ................................................................................................................... 10 7. Tax Incentives ................................................................................................................. 11 8. Taxes on Sugar and Junk Foods ..................................................................................... 11 9. Could legislation be introduced that would encourage a greater proportion of the population to take more exercise? ....................................................................................... 12 9.1 Transportation to Schools .......................................................................................... 12 9.2 Sport at school ........................................................................................................... 13 9.3 Teach Nutrition as a Life Skill ..................................................................................... 16 9.4 Local Heroes.............................................................................................................. 16 9.5 Providing Amenities ................................................................................................... 18 10. What can parents do? ................................................................................................... 19 11. Availability of healthy food ............................................................................................. 19 12. Misleading Food Labelling ............................................................................................. 20 13. Education ...................................................................................................................... 22 14. Responsible Food Retailing ........................................................................................... 23 14.1 Healthy affordable foods .......................................................................................... 24 15. How can we as a nation best effect change? ................................................................. 24 3 1. Key issues Education and public awareness We must create an environment where an effective education policy in relation to healthy nutrition is promoted and funded by government on an on-going basis. There is a case to be made for better educating health care professionals with a view to achieving the breastfeeding rates achieved in Sweden. Awareness of nutrition and physical activity should receive a greater prominence in the Social, Personal, and Health Education (SPHE) subject in Secondary Schools and throughout the secondary cycle. The sole criteria with regard to the food we serve in our school canteens, hospitals, care homes, prisons and canteens in State and semi-State companies should be quality nutrition, as opposed to convenience and cost. The targeting of small children by fast food giants should be curtailed immediately. The advertising campaigns of these companies should be closely monitored and regulated. All processed foods should be far more clearly labelled and without jargon particularly in relation to salt content, sugar content, calorific value and the quantifiable presence of trans-fats.2 It is at least worth considering a pilot of the ‘Traffic Light’ labelling approach. This simply lets the consumer know the typical values of salt, sugar, energy, fats and preservatives using a GREEN, AMBER and RED coding on the foodstuff’s label. This pilot could consider combining Guideline Daily Amounts (GDAs) and ‘Traffic Light’ labellng. The variety of sports and activities facilitated by schools should have a broader, more inclusive base, and should be participation- and enjoyment-focussed. We should launch a campaign to get more students walking and cycling to and from school. A ‘Cycle to School’ scheme should be put in place, similar to the ‘Cycle to Work’ Scheme. Alternatively, a scheme such as that in place in Scotland is needed to encourage schools to promote cycling.3 One Physical Education (PE) class per week for children is totally insufficient. We should be aiming at every schoolgoing child patricipating in a minimum of 30 minutes physical activity every school day (to take place within the school time). Unlike other fats, trans fat — also called trans-fatty acids — both raises your ‘bad’ (LDL) cholesterol and lowers your ‘good; (HDL) cholesterol. A high LDL cholesterol level in combination with a low HDL cholesterol level increases your risk of heart disease 3 The website of the Scottish scheme is available at: http://www.cyclingscotland.org/our-projects/awardschemes/cycle-friendly-schools 2 4 Young entrepreneurs An environment should be created so that young entrepreneurs aged between 17-23 years old who wish to enter the health and fitness sectors are not penalised by commercial rates, VAT, and the lack of available infrastructure. Tax incentives should be used to encourage these young entrepreneurs to invest in cookery schools, dance classes, walking tours, climbing walls, green grocers, sports clubs, after school activity centres, fitness centres, and sports summer camps. We should make sports and recreational facilities which are owned by the National Asset management Agency (NAMA) available to the public and roll them out via a network for ‘Local Heroes’.4 The provision of insurance for sports and physical activity-based enterprises has been both restrictive and inhibitive. We need a significant cultural change in the public’s to this issue, to include increased parental supervision and enforceable waivers. The dangers of taking healthy exercise are relatively minor in comparison to the long-term health risks in addition to the healthcare and quality of life costs of obesity to our society. Ireland’s food and retail industry The Oireachtas Joint Committee on Agriculture Food and Marine has called for the introduction of a statutory code of conduct in the grocery sector.5 Such a statutory code could consider a role for a ‘Food Ombudsman’ who could be appointed to work with the food industry. Supermarkets should be encouraged and given an objective of ensuring that at least as much floor and shelf space is given to whole foods, unprocessed fresh meats and fresh fruit and vegetables as is given to crisps, pizzas, confectionary, desserts, chocolate and alcohol etc. We must do more to promote farm shops and farmers markets, so that consumers have greater access to locally-produced, fresh, nutritious and reasonably priced fruit and vegetables. We should limit the amount of junk food served to children in leisure activity and play centres. 4 For a description of this programme see: http://www.rte.ie/localheroes/ See the Houses of the Oireachtas press release available online at: http://www.oireachtas.ie/parliament/mediazone/pressreleases/name-18591-en.html 5 5 2. 1. Prevention is better than cure – the context to childhood obesity Recent research has shown that overweight children develop more fat cells than healthy children thus increasing the likelihood that they will become overweight or obese adults. Overweight babies are more likely to become overweight adults. On the 13th of June 2013, Dr. Sinéad Murphy presented the committee with the following information:6 Ireland is ranked fifth highest among 27 European Union countries in terms of the incidence of childhood obesity.70% of obese children become obese adults. The cost of adult obesity to the state is in excess of €1 billion per annum, and will continue to rise unless childhood obesity is addressed. The average child who is obese, of whom there are 100,000 in Ireland, will cost in the region of €5,000 per year as a result of direct treatment for co-morbidities.7 1.1 The importance of breast-feeding as an early intervention measure In response to a question from Deputy Mitchell O’Connor, Dr. Sinéad Murphy also pointed out that there is no doubt but that breastfeeding is protective and is the best start a child can have from a nutritional point of view. It is also clearly an area where a vast improvement is needed in this country:8 “…we do not do well with breastfeeding in Ireland. It is very socioeconomically dependent, like everything else. However, we certainly should be encouraging it, as well as encouraging facilities and so on for mothers to be able to breastfeed where at all possible…Weaning is very important and we are bad at it…a little scarily, mothers will be advised to wean children at three months. This is a case then of educating, in that we talk about educating the educators and they are the pure educators, namely, the teachers. There also are the health care professionals who are going out and giving advice to these parents. They need to know what the advice should be and certainly, weaning at three months is not part of it. Moreover it happens and we hear frequently enough that mothers are advised to do this. This certainly is something that really requires quite a lot of attention. This will be very important from a prevention point of view as these are babies and hopefully we can prevent them from turning into overweight or obese children.” 6 A transcript of the relevant Joint Committee debate is available at: http://oireachtasdebates.oireachtas.ie/Debates%20Authoring/DebatesWebPack.nsf/committeetakes/HEJ2013061 300003 7 Comorbidity is either the presence of one or more disorders in addition to a primary disease or disorder, or the effect of such additional disorders or diseases. 8 Dr Sinéad Murphy speaking to the Joint Committee on the 13 th of June 2013. Transcript available at: http://oireachtasdebates.oireachtas.ie/debates%20authoring/debateswebpack.nsf/committeetakes/HEJ20130613 00003?opendocument#D00100 6 The importance of breastfeeding has been noted by the Economic and Social Research Institute (ESRI)9 which states that rates of breastfeeding in Ireland are very low by international standards with just over half of mothers (56%) currently initiating breastfeeding in Ireland compared to over 90% in Scandinavian states such as Sweden. ESRI notes that breastfeeding has been proven to reduce the risk of respiratory, ear and gastrointestinal infection in infants and that evidence is accumulating of longer term health benefits such as a lower risk of obesity and cardiovascular disease. The Department of Health and Children, in line with the World Health Organisation, recommend that babies should be exclusively breastfed for six months (not introducing any other food or drink). Mothers are also being encouraged to continue breastfeeding after that, in combination with complementary foods up until the age of two years.10 Source: ‘The Patterning of Breastfeeding in Ireland and Its Consequences: Evidence from the Growing Up in Ireland Cohort Study’ presented by Professor Richard Layte, ESRI, to the ESRI Conference entitled ‘Breastfeeding in Ireland 2012: Consequences and Policy Responses’. 9 ESRI press release , October 2012, available online at: http://www.esri.ie/news_events/latest_press_releases/breastfeeding_in_ireland_/index.xml 10 ‘The Benefits of Breastfeeding’, HSE/Cork University Hospital, available online at: http://www.cuh.hse.ie/Our_Services/Clinical_Services/Cork_University_Maternity_Hospital/Services_Provided/Ma ternity_Services/Breastfeeding_Support_Services/The_Benefits_of_Breastfeeding/ 7 2. Children and the excessive consumption of Junk Food Junk food is a term in common usage for food that is of little nutritional value and often high in fat, sugar, salt, and calories. Junk foods typically contain high levels of calories from sugar or fat with little protein, vitamins or minerals. One of the most alarming elements of mass junk food consumption, apart from obesity, is the fact that although our children are becoming more overweight, they are also under-nourished. The processing of junk foods, not only adds high levels of fats, salt and sugar, they also strip the constituent ingredients of vitamins, iron and fibre. So, many of the foods with the highest calorie contents also have the lowest nutritional values. 3. The problems facing teenagers Parental obesity may increase the risk of obesity through genetic mechanisms11 or by shared familial characteristics in the environment such as food preferences, sedentary lifestyle and the loss of traditional cooking skills. When children reach puberty and are overweight then chances are that they will not easily change established eating habits or be able to increase their levels of physical activity, without motivation, education, inspiration and support. When we look at the scale of the problem of teenage obesity in Ireland, the easy thing is to do nothing. But the cost of doing nothing and allowing today’s teenagers to become seriously unhealthy adults is economically prohibitive in addition to being socially unacceptable. Doing nothing or just giving up is simply not an option. The duration of night-time sleep may be a variable factor in respect of levels of physical activity—that is, teenagers who are more physically active may sleep longer at night and may have more energy to undertake this activity leading to a virtuous cycle. Television viewing or computer usage (especially social networking and gaming) may be a risk factor in obesity through a reduction in energy expenditure or because large amounts of time spent in sedentary activities may contribute to an impairment in the regulation of energy balance (by uncoupling food intake from energy expenditure). It is widely accepted that obesity among primary school children is at an all-time high, and that the rate of obesity seems to be accelerating. The problem seems to be accelerating faster in teenagers between 15 and 18 years of age than in any other age category. The 11 For a brief discussion of this mechanism see the Human Molecular Genetics Journal abstract to the article entitled ‘Genetics of obesity and the prediction of risk for health’ available online at: http://hmg.oxfordjournals.org/content/15/suppl_2/R124.full 8 reasons for this may include that they are more socially active, have more disposable income, are more susceptible to advertising and have unsupervised access to junk food, fizzy drinks and alcohol. The precise figures for obesity in the mid- to late-teens vary from region to another, but the one common denominator in all the research is that the problem is worsening. Obesity in teenagers is particularly difficult to tackle because behaviour patterns such as ‘vegging out’, socialising in fast food outlets, and missing out on home-cooked meals becomes reinforced by the strong bonds of group acceptance and the social dynamics of peer pressure. 4. Obesity and mental well being Apart from the long-term dangers of obesity, such as heart disease, cancer, stroke, diabetes, osteoporosis, arthritis, and, overall, a poorer quality of life we must focus our attention on the immediate effects of obesity on our teenagers’ mental wellbeing. Ms Grace O’Malley12 met with the Joint Committee on the 13th of June 2013 and summed up the serious situation in which Irish society finds itself and its relationship to childhood obesity: “We have a breakdown in society and this is the physiological symptom. Our children are getting obese and depressed and it is a symptom of society as a whole. We have a perfect storm. That is why we all need to work together to make a change.” Low self-esteem, coupled with a lack of assertiveness are often the precursor to being bullied, marginalised within a group, or even social exclusion. Not only do these feelings of isolation and rejection lead to comfort eating, highly addictive junk food binging and even bulimia, but all too often the results are deep depression and, tragically, suicide in some cases. We can no longer ignore the problem of obesity in children and young adults. To do nothing is no longer an option. We must educate, facilitate and motivate our young people to take the healthy options in life. 5. Publicly-funded Junk Food Critics of fast food restaurants are many, but ideas on how to replace them with healthy alternatives are in short supply. We as a nation cannot pontificate on this issue while we continue to serve junk food in our schools, hospitals, prisons, and retirement facilities etc. Is there a better example of how wrong this is than that of a hospitalised cardiac patient being 12 Senior Physiotherapist with the W82GO! Childhood obesity programme in Temple Street Hospital. 9 offered sausage, egg and chips the night before a bypass operation? It is time we got our own house in order. We must ensure that the food we serve in our public institutions is locally sourced, fresh, is highly nutritious, is cooked and presented with flair, passion and a minimum of waste. We must ensure that food served in schools, colleges, hospitals, prisons, canteens of government agencies and any other publicly-funded canteen are focussed on nutrition and not on what is cheap to prepare and easy to serve. There should be an immediate and outright ban on all forms of fried food in all of the above. 6. Food Heroes Because of the downturn in the economy there are hundreds of fantastic restaurants closed down in Ireland. Many of the Chefs who ran and/or worked in those establishments are wastefully unemployed. Their expertise is a valuable, extensive and immediately available resource that should, with their co-operation be utilised for the good of the country’s youth. These enthusiastic chefs are people who feel passionately about good food and who abhor the junk food culture. Shouldn’t we ask whether their skills could be employed in more productive ways? They have the talent and the passion to totally transform the way we as a society think about food in public institutions. Celebrity chefs have taken the fight for real food into hospitals schools and prisons in the United Kingdom with immediately very encouraging results. Having watched these documentaries and discussed them with other interested parties, the one thing we all agree on is that the most frustrating elements of the documentaries was just how difficult it was to manage change when it was resisted by those on budget committees and school boards who lacked the vision for change. We must encourage those in such positions of responsibility not to be afraid to stretch themselves outside their comfort zones when they should appreciate the obvious benefits of change from stodgy junk to healthy foods which could actually save money. However, here in Ireland we don’t need the ‘celebrity chefs’ the UK relies on to head up similar projects. We have a pool of talent available with the knowledge, the skill-sets and the drive to manage the changes needed and make the transition from a culture of publicly funded junk food to one that is grounded within the core principles of fresh, nutritious, locally produced, and unprocessed wholefood dining. 10 Unemployed chefs could also teach our children in schools to care about what they eat, how it is sourced and how they cook it as part of the school curriculum or indeed as a feature of transition year. They could bring a more exciting dimension to home economics and could involve all students and not just the ones who take the home economics class. Students will not only learn a valuable life skill, but they will also develop a healthy respect for good food. 7. Tax Incentives This is an opportune time to use tax incentives in a positive way to promote healthy living. By offering, tax breaks, Commercial Rates exemptions and VAT exemptions to businesses like Juice Bars, Gyms, Tennis Clubs, Farm Shops, Cookery Schools, Yoga classes, Aerobics and dance classes, hill walking, aqua sports, paint ball and activity sports operators, we can stimulate economic activity, create jobs and build long term positive social infrastructure. By creating an environment of opportunity for those who wish to pursue careers in the health and fitness field it will be easier to educate our young people to lead more healthy, and active lives. If this can be done then we will all benefit as a result. If we are serious about addressing the insidious social evil of obesity then we have to take bold and courageous action. We have to challenge our decision and policy makers to move out of their comfort zone and force them to ACT and not allow them to prevaricate or to procrastinate. The long-term medical costs of doing nothing far outweigh the costs of creating the environment for positive change. 3. 8. Taxes on Sugar and Junk Foods If our aim is to protect, to educate, to offer healthy alternatives to the public, then we must be both even-handed and holistic in our approach. Foods high in trans fats, sugar, salt, monosodium glutamate (MSG), and potentially harmful food additives must be targeted with equal vigour. It must be a level playing field, otherwise a tax on sugary drinks will draw the criticism that it is no more than a cynical headline grabbing and revenue gathering exercise. Other industries have contributed to community awareness of health problems such as the alcohol industry and the drink aware program. A possibility to consider would be for Government to approach industry in relation to a voluntary levy and participation in supporting community programmes. A voluntary levy could be ring fenced in respect of the issues which were brought to the attention of the Join Committee by Grace O’ Malley on 13th June 2013: 11 1. Sustainable Government funding for the evidence based temple street hospital W82Go! Treatment programme for children who are clinically obese; 2. Co-ordinated and sustainable funding of an evidence-based community treatment programme such as Up4it! that could be rolled out nationwide over a targeted time period that builds capacity through multi-stakeholder delivery partnerships and utilisation of local engagement models and resources; and 3. Appointment of a national post for obesity management to co-ordinate the clinical service delivery of obesity treatment in an integrated pathway between hospital and community. This approach reflects the concerns of the food and drink industry regarding the imposition of a saturated fat tax, which was brought to the committee’s attention in October 2012. If revenue is to be gathered from the imposition of a tax or levy on the wide range of foods and drinks that are at the core of the obesity pandemic, then it must be shown that this money will be ring fenced and channelled into schemes that will promote healthy sports and activity for young and old alike. This revenue should be centrally collected and entitled in such a way that transparently promotes this ringfencing, for example, ‘The Healthy Life Fund’. This fund should be supplemented from National Lottery funding until such time as sufficient revenue from a junk food tax would allow it to be self-financing. Financing should be fed into communities to aid and develop school gyms, small athletic clubs, and everything from youth football, minority sports promotion, to active retiree support groups. This money should also be used for an on-going public information campaign with television and radio infomercials, newspaper and magazine articles and motivational posters on billboards, bus shelters and city buses. This campaign will be designed to ‘Educate, Motivate and Encourage’. 4. 9. Could legislation be introduced that would encourage a greater proportion of the population to take more exercise? Issues that must be addressed in planning and implementing physical activity–based programmes in both primary and secondary schools, include transportation, qualified supervision, selection of activities to meet student needs and interests, and access to appropriate facilities. 9.1 Transportation to Schools Schools’ have played a central role in the provision of physical activity to children for more than a century. Physical education (PE) has been an institution in private schools since the 12 late 1800’s, and school sports have been a growing component of the educational enterprise since the early 1900s. Traditionally, students have engaged in physical activity during recess breaks in the school day and by walking or riding bicycles to and from school. However, in the 21st century, alarming health trends are emerging, suggesting that schools need to renew and expand their role in providing and promoting physical activity for our nation’s young people. In recent times trips to and from school by walking and cycling have dramatically decreased. The studies I have seen of walking to school have been based abroad. We don’t necessarily need to spend public money on a similar study in Ireland as the results are self-evident, i.e. that children who walk or cycle to school get more physical activity than children who are ferried in motor vehicles.13 An American study undertaken to determine the prevalence of walking and biking to school at 8 urban and suburban schools in a city, stated that: “The vast majority of students rode a school bus or were driven to school; only 5% walked or rode a bike to school”.14 And this is noteworthy as 35% of students lived less than one mile from the school. In Dundalk, for example, one of the most divisive issues in public planning in recent years has been the installation of cycle lanes in areas of the town where secondary schools are located. The work involved in the installation was lengthy and obstructive to motorists because their locations were in old and built up areas of the town where the roads could not be widened. Advocates for the lanes and the critics against them became embroiled in a very polarised and heated debate as to the effectiveness, cost and inconvenience of the lanes. Cycle lanes should, in principle, be supported. However, we need to see a greater uptake of the facility by the students they were designed and intended for. Equally, we need to arrive at a situation whereby new school developments will view the non-obstructive installation of cycle lanes as a core priority in the planning process. 9.2 Sport at school Schools should ensure that all children participate in a minimum of 30 minutes of moderateto-vigorous physical activity during the school day; this includes time spent being active in PE classes. Additional physical activity should be provided through extracurricular and schoollinked community programs. They should ensure that PE is taught by certified and highly Recent research from Denmark also suggests that children’s academic performance also benefits from walking/cycling to school. See the ScienceNordic article entitled ‘Children who walk to school concentrate better’ available online at: http://sciencenordic.com/children-who-walk-school-concentrate-better 14 http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/114/11/1214.full 13 13 qualified PE teachers at all levels. Montessori schools and crèches should provide children with at least 30 minutes of break time during each school day to run about and play free from restriction. At the presentation made to the committee on the 14th of February 2013 by Dr. Karl Henry from operation transformation he mentioned that as a nation, we once had a problem with honours level mathematics. This was addressed by way of giving extra points to those students who took honours mathematics. We believe the same incentive should be put in place for physical education. Many programmes are highly dependent on teacher interest and availability. Often teachers volunteer to manage or supervise after school student clubs, and sports teams. Although stipends are available for some student activity support, they may not be available for physical activity–based clubs. The additional potential insurance liability of physical activity may deter schools from sponsoring such activities. We must address this element. Every physical activity carries a risk, but the risks to our children from leading uneventful and sedentary lives make the risk of playing sports one worth taking. There is nothing wrong with schools doing all they can to procure success on the sports field; however, our interest should be in broadening the base of student participation in sport and not just in the cultivation of elite athletes. Furthermore, highly competitive sports programmes may not be reinforcing positive health aspects of sports participation. Although sports provide a portion of the student population with significant amounts of physical activity, the remainder of the students may be very sedentary and represent those who most need greater amounts of physical activity. In fact, in large schools, access to sports facilities may be limited to a much smaller percentage of the student body. Most athletic teams are of similar size, and although large schools may offer more sports than smaller ones, the total number of students that can be served does not increase proportionately to enrolment. If, for example, we have a large secondary school with 200 or so 14 to 15 year olds, and the school is focused on only one kind of sport (Hurling or Rugby for example) only the elite of perhaps 20 students will make the panel for the team in that age category. That being the case, what happens to the other 180 children who are rejected by the elitist and competitive nature of the performance centred system? The simple answer is that they are left behind! 14 Not every child can excel at, or even want to participate in, sports like Football, Rugby or Basketball. We should see greater effort put into introducing new sports into schools like Badminton, Squash, Handball, Indoor Climbing, and Gymnastics.. The emphasis should be on participation rather than competition. Every one of these sports has the potential to stimulate physical activity, increase social activity centred around sport, and introduce impressionable minds to valuable life skills such as team work, comradeship, and dealing with the successes and disappointments of competition. No child should be left behind because of lack of opportunity or ability. There is a sport for everyone and we should do more to ensure that young people can find their niche when it comes to developing an interest in sport. It may not be possible for a school to obtain the services of a coach for one of these activities on a full time basis, so they can either engage the services of private contractors on a once or twice a week basis, during school hours, (as schools currently do with music teachers) or, alternatively, that schools on a local basis cooperate to jointly form clubs to promote minority sports and fund the coaching out of grants from The Healthy Life Fund. Schools are potentially attractive settings in which to promote positive health behaviour because students spend large amounts of time in the school environment. Elements of the traditional school curriculum relate directly to health, and schools can provide extracurricular programmes that can promote health. Although schools are under increasing pressure to increase student performance in the Leaving Certificate, the recent dramatic rise in the prevalence of obesity in children and adolescents in Ireland suggests that there is a pressing need for the nation’s schools to systematically and effectively promote environments and opportunities that will prevent the spread of obesity. Physical activity is a key determinant of weight status In children generally and teenagers in particular. Disquieting trends among teenaged children in Irish society, such as increased ‘screen time’, video game playing that borders on the obsessive, and decreased reliance on physically active transport, indicate that the schools should assume a leadership role in ensuring that young people engage in adequate amounts of physical activity each day. These policy initiatives, if fully implemented, would position Irish schools as societal leaders in addressing the enormous public health challenge of obesity. Furthermore, studies have shown that concentration levels, and test results of students in academic fields increased dramatically when daily physical exercise became part of the school curriculum. This improved academic performance across the board. However, it is most noticeably prevalent in boys aged between 14 years and 18 years. 15 Finally, we should make sports and physical activity a compulsory part of the school curriculum and award merits every year of secondary school (including transition year) not for excelling at one sport or another, but for application and enthusiasm, team work and morale building, courage and good sportsmanship. These merits can translate into additional leaving certificate points, or they could speak volumes to a future prospective employer about the good character of the student standing in front of him asking for a job. 9.3 Teach Nutrition as a Life Skill As part of an overall education programme, a national government long term strategy for promoting healthy eating among young people needs to be undertaken without delay to undo the damage that years of exposure to junk food promotional advertising has done to their eating behaviours. Perhaps one such initiative could be where every secondary school could have a twiceweekly healthy eating stall promoting fruit and vegetables. This could be undertaken as a transition year project wherein the students could learn about running a business, come up with innovative ideas as to how healthy eating could be promoted amongst their peers and also how a minimum of preparation is all that is necessary to transform basic ingredients into healthy tasty snacks, such as hummus, guacamole, and spicy salsa served with carrot, cucumber and celery sticks. A National Cookery Competition, using the finest Irish natural ingredients and along the lines of ‘Masterchef’ should be set up with the top team from each school competing at district, county and national level to find the most innovative young chefs in the country. 9.4 Local Heroes In every town and village in Ireland there are wonderful and dedicated people who give of their time and expertise to sports and community groups to promote and develop the stars of tomorrow. But despite the fact that all their endeavours are born out of love and commitment for their sport, it must sometimes feel like they are ploughing a lonely furrow because there are no national support structures to aid and assist them. In the case of this Committee’s Rapporteur he was heavily influenced and inspired by retired players in my local Clan Na Gael Club in Dundalk. Childhood heroes became mentors and friends. These Local Heroes are the backbone of every community. They are always the first to volunteer for any project and the ones who turn out the lights when there is work to be done. 16 These amazing people are uniquely placed to assess the needs of the local sports and activity groups. They are the unpaid stakeholders in the character building process of involving young people in sport. To borrow from the Indian writer Rudyard Kipling, under their guidance youngsters learn to dream but not make dreams their master; think, yet not make thought their aim; they learn to meet with triumph and disaster and treat those two imposters just the same, they fill the unforgiving minute with sixty seconds worth of distance run. The late Detective Adrian Donoghue was such a Local Hero. We, as a society, owe a huge debt of gratitude to him and all our local heroes for the selfless, tireless and passionate commitment they have given to the young people of Ireland and decision-makers should be urged to involve them in both planning and funding decisions in relation to how sport and recreation is developed within the community. The zeal of health and safety regulations coupled with a relentless, and bogus claims culture has resulted in padlocks on parks, football pitches and school grounds. If a footballer breaks his arm during a game at his local club, everyone will say “Hard luck - I hope you get back playing soon”. However, if he had fallen on a piece of land owned by the local Council he would have had a dozen offers of ‘a good solicitor’ before he reached the side-line We simply must be able to utilise all sports and recreation resources that are available and bypass the red tape if we are to get our young people involved in sport. Government money was spent on school gyms all over the country, yet they are closed at weekends and during school holidays. This is not only a waste but a missed opportunity. Local heroes can help manage these facilities to provide badly needed fitness and recreational facilities to their community. It is ridiculous that notices are routinely put up on green areas of housing estates requesting the public toing “Please keep off the grass”. Young people who should be out playing football etc. are discouraged and the eventual outcome is that they spend their time watching television or playing computer games. If a college student, for example, wants to run a summer school during the holidays coaching football, tennis, or basketball a series of obstacles are sometimes placed in their way. Some of these involve necessary regulations which the Joint Committee fully supports but others involve a lack of co-operation from local organisations or school boards of management. Why can’t we focus on making facilities accessible to local heroes instead of placing obstacles in their way? 17 9.5 Providing Amenities We in Ireland are in a unique position, which more often than not is viewed as being a negative and that is that we, the Nation, now own financial institutions. These same financial institutions have unused buildings on their books that could be used to provide facilities for social recreation. Indeed some of these idle properties have fully equipped gyms and fitness centres. For example, three such unused facilities are in Dundalk. One was an Ice Skating rink, another a hotel with not only a golf course and a leisure complex but also a number of indoor tennis courts and football pitches, and the third was one of the finest fitness facilities in the country. Presently all three are closed down and are a tragic waste of, what are essentially, National resources. These facilities are badly needed in the community but are unused, yet bizarrely facilities like these all over Ireland are still costing money to secure and maintain even as they lie idle. It is to be hoped that, in time, the Dundalk Institute of Technology will procure one of these facilities and make it available to not only the students on the Campus but also to the broader public. If these are available in Dundalk, imagine the situation replicated throughout the country, and suddenly a vast array of facilities and opportunities emerge. Apart from properties which are suitable for fitness and recreational activity, financial institutions are in possession of large amounts of liquidated and repossessed fitness equipment which is costing money to store, which is depreciating all the time, and which enthusiastic, newly qualified and entrepreneurial young people cannot get the finances to purchase. There are thousands of unemployed, but highly skilled, qualified and experienced, fitness and dance instructors, tennis, football, swimming and athletics coaches. Their education cost valuable State resources, and it is soul destroying for these young people to embrace the possibility that they might never have the opportunity to either get a job in their chosen profession, or be able to set themselves up in business. We, as a nation, in the fight to change our eating habits and to stimulate a national fitness revolution urgently need the energy, expertise, enthusiasm and commitment of these bright and dedicated young people. Let’s not send them away to follow their dreams in foreign lands because of a lack of opportunities at home. 18 10. What can parents do? Parents can instil in their children from a young age the benefits of sport and physical activity as well as learning about the food / activity balance. At a committee meeting on the 14th February 2013 stakeholder Dr. Eva Orsmond brought to our attention the fact that parents did not know what their children should weigh, and that parents should be aware of what their children weigh. She recommended that every time a child visits their General Practitioner they should be weighed. Weighing children also creates an opportunity for an early intervention before the problem develops into a chronic illness. Encouraging children to become active and resist the urge to slouch in front of the television is a first step. How parents choose to live their lives and motivate themselves is reflected in their children’s behaviour patterns. Children learn from what they see around them. Parents are children’s most powerful role models. Parents can and should lead by example. Physical activity can do more than just help your child’s waistline, it can make them healthier by: Relieving stress; Improving sleep; Making bones and muscles stronger; Making them feel full of energy; Building strength and endurance; Elevating self-esteem and giving them something to do that is positive and selfaffirming; Providing a way to connect to family and friends; Having a stronger heart and lungs; Reducing symptoms of anxiety and depression; Lowering blood pressure and cholesterol; Preventing chronic disease, like cancer, heart disease, type 2 diabetes, osteoporosis; arthritis, Sleep Apnoea, and of course Obesity; and Prolonging a higher quality of life and independence as we get older. 11. Availability of healthy food Some parents find it difficult to cook a family meal in the evening after spending the day at work. It is easy to buy a meat and two veg dinner, or a salad to take away at lunch time. Garages and corner shops all over the country now have in house deli counters and offer this luncheon facility. However the problem for the parent who wishes to buy a nutritious family meal becomes evident once six o’clock comes around, as it is often very difficult to buy home cooked food to take away and all that is available is processed, deep fried food (pizzas and curries, etc.). 19 This is an area where Local Authorities and Central Government need to regulate. Delicatessens and healthy sandwich bars should be encouraged to remain open until at least 8.00 pm. We, as a society, should ensure that there is a healthy alternative to junk food for family evening meals. Extended trading hours could be a condition of planning permission for delicatessens and carvery style food retailers, whci sell wholesome food to take away. 12. Misleading Food Labelling Accurate, easy to read, and scientifically accurate nutrition and health information on food labels is an essential component of a comprehensive public health strategy to help consumers improve their diets and reduce their risk of diet-related diseases. Dr. Eddie Murphy presented to the committee on the 14th of February 2013. He mentioned the ‘Count me in’ campaign. It’s very simple - beside the price on the menu one can see the calories in an item. It gives the consumer the chance to make informed decisions about what they are buying. In July 2012, the Food Safety Authority of Ireland published the findings of its national consultation on displaying calories on menus in Ireland. Calories on Menus in Ireland – a Report on a National Consultation recommended the introduction of a calorie menu labelling scheme for food service businesses. The report also recommended that the scheme should be operated on a voluntary basis initially to allow a period of time for the development of a system, including technical tools, to support the food service sector. It also noted that 96% of people wanted calorie posting.15 Improved food labelling could provide consumers with easy-to-read nutrition and ingredient information that they can use to reduce their risk of the leading causes of death in Ireland today, including heart attack, stroke, certain forms of cancer, Polycystic Ovary Syndrome (PCOS) and diabetes. No matter how committed to healthy eating, no matter how highly educated or informed the consumer may be, he/she simply cannot make informed intelligent choices if the information he/she is relying on is ambiguous, misleading, and disingenuous on the packaging of a product on the supermarket shelf. The labelling of foods, specifically all forms of processed foods, should be done to a ‘Universal Gold Standard’, whereby, the fat content, and the nature of those fats, additives, flavour enhancers, energy and nutrient content should be clearly and unambiguously displayed in such a way that a ten year old child could understand it instantly. 15 See FSAI press release available online at: http://www.fsai.ie/news_centre/press_releases/calories_on_menus_report/04072012.html 20 Health-conscious people who are careful about what they buy, particularly in supermarkets, are more likely to be influenced by advertising than they are by what appears on the label of the product, which for anyone who is not a nutritionist or a code breaker are at best confusing and at worst deliberately misleading. Energy contents are often expressed in “calories”, “Calories”, “Kcals”, “Joules” and “Kilojoules”. Without a science degree the ordinary shopper can get confused very easily. Notwithstanding the difficulties with varying terminologies, there is no precise measurement benchmarked standard so that the consumer can compare like with like. Product lists for energy content range from Kcals per gram, Calories per Millilitre (ml), per 100 gms, per kilo, or per litre, some products even list the energy content in: Calories, Kcals, or even Kjoules per portion, usually these “portion” sizes are fine for a four year old child but a bit on the small side for an adult, but it is quite a clever way of disguising the true content of the product. A few simple definitions may help: simply put a calorie, (small c), is the unit of thermal energy required to heat 1 gram (or 1 CC at 4C), of pure water at atmospheric pressure by 1 degree centigrade. A Calorie (notice the capital C), or Kilocalorie, (Kcal) is the unit of energy required to heat one Litre of water by one degree. Therefore, a “Calorie” has one thousand times the potential heat energy of a “calorie”. It would be interesting to conduct a poll to ascertain just how many food shoppers actually know this fact on a given day. Recommended daily calorie intake varies from person to person, but there are guidelines for calorie requirements we can use as a starting point. The UK Department of Health Estimated Average Requirements (EAR) suggests a daily Calorie (Kcal) intake of 1940 Calories per day for women and 2550 for men. Or more simply put, the average woman with an average work load needs as much energy every day that would boil 20 litres of water from freezing point and the average man would require the energy to boil 25 litres of water from freezing point. Daily Calorie requirements can vary greatly depending on lifestyle, metabolism and other factors. Factors that affect your personal daily calorie needs include your age, height and weight, your basic level of daily activity, and your body composition. When consumers grasp the concepts of how energy measurements are expressed by thinking of it in simple and not abstract terms, they will feel more able to make informed choices. 21 Calories come from three main sources; Sugars, Carbohydrates and Fats. Some food labelling gives a breakdown in each category and the calorific content; some even break down the fat content into Saturated and Unsaturated fat percentages. Food labelling should be regulated so that it is taken out of the hands of advertising executives, spin doctors and in-house lawyers. It should inform, not confuse and it should conform not only to the letter of the law, but also to the spirit of the law. A ‘Food Ombudsman’, who would be independent of government and should have the authority to control and regulate the labelling on such foods, and this office should have the authority to force food processors to include health warnings clearly on the packaging, in cases where he deems the product to be more junk than nutritious. As a food producing country we should strive to set standards, in food production, labelling and description. We should strive not only to meet minimum EU requirements, but to surpass them. Our standards should be the benchmark that other countries can only aspire to. 13. Education Of course all the food labelling in the world will only have limited effectiveness if we do not educate people how to interpret the information, and decipher the jargon on the product so that he can make informed choices. Children, by and large, learn from their parents and form their dietary habits from them. If we want our children to recognise the value of eating for nutrition as opposed to eating badly out of force of habit, then we need to break the cycle of ignorance and educate their parents first. It will never be enough to tell people that Product A is “bad for you” until we educate them as to health giving alternatives. Consumers are routinely misled by claims on food packaging. The marketing behind these strategies believe that with the right wording, prominently placed on the product and on the advertising, that they can subliminally sell the message that junk food is healthy food, or at least more healthy than its competitors on the shelf. Claims such as “low sugar”, “low salt”, “low fat”, “fat free”, “no artificial sweeteners” etc. to the untrained eye all appear to be positive messages. However, stating something is “low salt”, or “reduced salt”, which doesn’t have salt, but which may have a high sugar or fat content, is misleading and not helpful to the consumer. Likewise, items that are saturated with sugar often claim to be “low fat” (which may be true), and products containing high fat content, are just as likely to be proclaiming the merits of having a low sugar content. We need to have an overall strategy that stops the consumer getting sucked into marketing loopholes. 22 One particular campaign by a fast food giant makes huge capital out of the claim that all their beef and pork sold in Ireland is sourced in Ireland. This is a deliberate attempt to link their heavily processed end products with the excellent reputation that Ireland has established for the production of high quality meats. This approach mirrors the sponsoring of sports events by fast food companies and soft drinks companies. It is only when we can educate consumers via a national media campaign, when we target children in school, as part of a life skills programme, (perhaps in transition year), that they will become sufficiently sceptical of claims on food packaging and perhaps they could carry it back to the rest of the family. Transition year students are at an age when they are naturally curious, creative, talkative and assertive, so in starting with their education in relation to food labelling, could be the first domino in a long chain reaction in the battle to increase general public awareness. 14. Responsible Food Retailing When visiting local shops one is struck by the huge variety of pizzas, ready-made burgers and TV dinners on offer in the chilled foods section. If one wants to to buy fish one’s options tend to be limited to either fish fingers or fried processed fish in batter. Some shop-owners have indicated that they are in the business of giving his customers what they want. It’s difficult to argue with this logic. In bigger supermarkets fruit and vegetables are displayed around the periphery of the store while the central isles are jam packed with highly processed convenience foods that are stripped of nutrients, packed full of trans fats, salt, sugar flavour enhancers and preservatives. If we consider the floor space given over to biscuits, sweets, confectionary, crisps, sugary drinks, frozen pizza, chips and ready-meals, cheaply made white bread, and of course alcohol it does not compare well with the space given to fresh fruit and vegetables. For example, one of the stakeholders who met with the committee pointed out on October 2012 that many products appealing to children are placed lower on shelving rather than at a height for parents and adults. She also mentioned the Irish Heart Foundations research from 2007 highlighted the availability of foods stuffs under discussion. Some 74% of post- primary schools provided confectionary for sale. Up to 45% of schools had drink vending machines, 57% sold salty snacks and crisps and 52% sold sugary carbonated drinks. This undermines attempts by schools and the curriculum authors to promote healthy eating and healthy lifestyle. Only 30% of post primary schools had healthy eating policies and more than 90% of 23 schools called for a code of practice for industry sponsorship and provision and content of vending machines. 14.1 Healthy affordable foods As a priority, we as a society must put in place measures to increase access to high quality affordable, locally sourced nutritious foods either through improvements in supermarkets, or more local grocery stores, and we must put in place a benign environment for the growth and proliferation of farmer’s markets and by extension, we should create an environment where the consumer can deal directly with a farmer or horticulturalist in his local area thus having access to high quality fresh seasonal fruit and vegetables. Research shows that having a supermarket in a neighbourhood selling fresh fruit and vegetables has many positive effects on lowering the body mass index among adolescents living in that vicinity. Yet, many families do not have access to fresh healthy affordable foods locally. This is especially true in lower income communities where convenience stores and fast foods restaurants are widespread, but supermarkets, green-grocers and farmers’ markets are scarce. Some countries, and states within the United States of America, provide practical advice and assistance to retailers to explain the benefits of selling health foods and how best to innovate in this way.16 15. How can we as a nation best effect change? We as a nation need to come at the problems of poor diet and lack of physical exercise from many different angles in order to defeat the obesity pandemic. By adopting positive approaches we will achieve longer lasting social benefits. We shouldn’t be afraid to try new things. We shouldn’t be afraid to take risks, and we shouldn’t be afraid to take unpopular decisions in order to fight the good fight. Just because we haven’t tried a tactic in the past does not mean it is going to fail. So we shouldn’t allow the fear of failure to stop us trying a new approach either. So far countries all over the world have approached the obesity pandemic with linear and formulaic tactics and failed. New thinking and nationally coordinated, multi-faceted strategies to implement them are absolutely essential if we are to achieve the core objectives of a healthier, better educated, more self-reliant and more active population. See, for example, the California Department of Public Health’s Network for a Healthy California—Retail Program Retail Fruit & Vegetable Marketing Guide (June 2011) For an overview of a range of measures undertaken in the United States of America see the Center for Disease Control leaflet entitled ‘DNPAO State Program Highlights - Improving Retail Access for Fruits and Vegetables’ available online at: www.cdc.gov/obesity/downloads/improvingretailaccess.pdf 16 24 There will always be people who will try and convince us that the word ‘CHANGE’ has the same meaning as the words ‘BAD’ and ‘WRONG’. The processed foods and drinks industries should themselves embrace the challenge of change. They will need to become more flexible and adaptive in order meet the needs and demands of a better informed, more selective and nutritionally focused society. 25 26 SECTION 2: LIST OF THOSE WHO PRESENTED TO THE COMMITTEE Senator Eamon Coghlan Irish Sports Council Professor Carlos Blanco Professor Donal O’Shea Professor Niall Moyna Professor Mark Hanson Murduff Wholesale Limited Safefood Ireland Food and Drink Industry Ireland Irish Heart Foundation Special Action group on obesity Nutrition and Health Foundation Institute of Leisure & Amenity Management Operation Transformation Temple Street Children’s University Hospital Irish Nutrition and Dietetic Institute 27 28 SECTION 3: ORAL PRESENTATIONS Senator Eamon Coghlan http://www.oireachtas.ie/parliament/media/committees/healtha ndchildren/Pilot_Programme_Eamonn_Final.pdf Irish Sports Council http://www.oireachtas.ie/parliament/media/committees/healtha ndchildren/Remarks-by-John-Treacy-to-Joint-Committee-onHealth-190412.docx Professor Donal O’Shea http://www.oireachtas.ie/parliament/media/committees/healtha ndchildren/Presentation-to-Committee-26.04.2012.pdf Professor Carlos Blanco and Professor Mark Hanson http://www.oireachtas.ie/parliament/media/committees/healtha ndchildren/Prof-Blanco-Presentation.pdf Professor Niall Moyna http://www.oireachtas.ie/parliament/media/committees/healtha ndchildren/Final-Obesity---Oireachtas-April-26,-2012-.pdf Murduff Wholesale Limited http://www.oireachtas.ie/parliament/media/committees/healtha ndchildren/J63-Murduff-Presentation-on-Obesity.docx Safefood Ireland http://www.oireachtas.ie/parliament/media/committees/healtha ndchildren/J63-Childhood-Obesity-Presentation-for-Thursday.pptx Food and Drink Industry Ireland http://www.oireachtas.ie/parliament/media/committees/healtha ndchildren/J64-FDII-presentation-to-the-Joint-OireachtasCommittee-on.ppt http://www.oireachtas.ie/parliament/media/committees/healtha ndchildren/J64-JOC-submission.doc Irish Hospice Foundation http://www.oireachtas.ie/parliament/media/committees/healtha ndchildren/IHF-Opening-Statement.pdf Irish Heart Foundation http://www.oireachtas.ie/parliament/media/committees/healtha ndchildren/IHF-Submission.pdf 29 Special Action group on obesity http://www.oireachtas.ie/parliament/media/committees/healtha ndchildren/Oireachtas-SAGO.doc Nutrition and Health Foundation http://www.oireachtas.ie/parliament/media/committees/healtha ndchildren/NHF-presentation-for-JOC-Health-and-Children13.11.12-for-Mary.pptx Institute of Leisure & Amenity Management http://www.oireachtas.ie/parliament/media/committees/healtha ndchildren/J68-ILAM-Oireachtas-Committee-Presentation.Nov2012.ppt Operation Transformation http://www.oireachtas.ie/parliament/media/committees/healtha ndchildren/Operation-Transformation-Oireachtas-PresentationAA.ppt Temple Street Children’s University Hospital and Irish Nutrition and Dietetic Institute http://www.oireachtas.ie/parliament/media/committees/healtha ndchildren/Tackling-Childhood-Obesity_Health-Comm_Openingand-Closing-FINAL.doc 30 SECTION 4: TRANSCRIPTS OF HEARINGS 13 June 2013 http://oireachtasdebates.oireachtas.ie/Debates%20Authoring// WebAttachments.nsf/($vLookupByConstructedKey)/committees~ 20130613~HEJ/$File/Daily%20Book%20Unrevised.pdf?openelem ent 14 February 2013 http://oireachtasdebates.oireachtas.ie/Debates%20Authoring// WebAttachments.nsf/($vLookupByConstructedKey)/committees~ 20130214~HEJ/$File/Daily%20Book%20Unrevised.pdf?openelem ent 26 April 2012 http://oireachtasdebates.oireachtas.ie/debates%20authoring/de bateswebpack.nsf/committeetakes/HEJ2012042600001?opendoc ument 19 April 2012 http://oireachtasdebates.oireachtas.ie/debates%20authoring/de bateswebpack.nsf/committeetakes/HEJ2012041900001?opendoc ument 15 November 2012 http://oireachtasdebates.oireachtas.ie/Debates%20Authoring// WebAttachments.nsf/($vLookupByConstructedKey)/committees~ 20121115~HEJ/$File/Daily%20Book%20Unrevised.pdf?openelem ent 11 October 2012 http://oireachtasdebates.oireachtas.ie/Debates%20Authoring// WebAttachments.nsf/($vLookupByConstructedKey)/committees~ 20121011~HEJ/$File/Daily%20Book%20Unrevised.pdf?openelem ent 4 October 2012 http://oireachtasdebates.oireachtas.ie/Debates%20Authoring// WebAttachments.nsf/($vLookupByConstructedKey)/committees~ 20121004~HEJ/$File/Daily%20Book%20Unrevised.pdf?openelem ent 31 32 SECTION 5: TERMS OF REFERENCE TERMS OF REFERENCE a. Functions of the Committee – derived from Standing Orders [DSO 82A; SSO 70A] (1) The Select Committee shall consider and report to the Dáil on— (a) such aspects of the expenditure, administration and policy of the relevant Government Department or Departments and associated public bodies as the Committee may select, and (b) European Union matters within the remit of the relevant Department or Departments. (2) The Select Committee may be joined with a Select Committee appointed by Seanad Éireann to form a Joint Committee for the purposes of the functions set out below, other than at paragraph (3), and to report thereon to both Houses of the Oireachtas. (3) Without prejudice to the generality of paragraph (1), the Select Committee shall consider, in respect of the relevant Department or Departments, such— (a) Bills, (b) proposals contained in any motion, including any motion within the meaning of Standing Order 164, (c) Estimates for Public Services, and (d) other matters as shall be referred to the Select Committee by the Dáil, and (e) Annual Output Statements, and (f) such Value for Money and Policy Reviews as the Select Committee may select. (4) The Joint Committee may consider the following matters in respect of the relevant Department or Departments and associated public bodies, and report thereon to both Houses of the Oireachtas: (a) matters of policy for which the Minister is officially responsible, (b) public affairs administered by the Department, 33 (c) policy issues arising from Value for Money and Policy Reviews conducted or commissioned by the Department, (d) Government policy in respect Department, of bodies under the aegis of the (e) policy issues concerning bodies which are partly or wholly funded by the State or which are established or appointed by a member of the Government or the Oireachtas, (f) the general scheme or draft heads of any Bill published by the Minister, (g) statutory instruments, including those laid or laid in draft before either House or both Houses and those made under the European Communities Acts 1972 to 2009, (h) strategy statements laid before either or both Houses of the Oireachtas pursuant to the Public Service Management Act 1997, (i) annual reports or annual reports and accounts, required by law, and laid before either or both Houses of the Oireachtas, of the Department or bodies referred to in paragraph (4)(d) and (e) and the overall operational results, statements of strategy and corporate plans of such bodies, and (j) such other matters as may be referred to it by the Dáil and/or Seanad from time to time. (5) Without prejudice to the generality of paragraph (1), the Joint Committee shall consider, in respect of the relevant Department or Departments— (a) EU draft legislative acts standing referred to the Select Committee under Standing Order 105, including the compliance of such acts with the principle of subsidiarity, (b) other proposals for EU legislation and related policy issues, including programmes and guidelines prepared by the European Commission as a basis of possible legislative action, (c) non-legislative documents published by any EU institution in relation to EU policy matters, and (d) matters listed for consideration on the agenda for meetings of the relevant EU Council of Ministers and the outcome of such meetings. (6) A sub-Committee stands established in respect of each Department within the remit of the Select Committee to consider the matters outlined in paragraph (3), and the following arrangements apply to such sub-Committees: (a) the matters outlined in paragraph (3) which require referral to the Select Committee by the Dáil may be referred directly to such sub-Committees, and (b) each such sub-Committee has the powers defined in Standing Order 83(1) and (2) and may report directly to the Dáil, including by way of Message under Standing Order 87. 34 (7) The Chairman of the Joint Committee, who shall be a member of Dáil Éireann, shall also be the Chairman of the Select Committee and of any subCommittee or Committees standing established in respect of the Select Committee. (8) The following may attend meetings of the Select or Joint Committee, for the purposes of the functions set out in paragraph (5) and may take part in proceedings without having a right to vote or to move motions and amendments: (a) Members of the European Parliament elected from constituencies in Ireland, including Northern Ireland, (b) Members of the Irish delegation to the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe, and (c) at the invitation of the Committee, other Members of the European Parliament. b. Scope and Context of Activities of Committees (as derived from Standing Orders [DSO 82; SSO 70] (1) The Joint Committee may only consider such matters, engage in such activities, exercise such powers and discharge such functions as are specifically authorised under its orders of reference and under Standing Orders. (2) Such matters, activities, powers and functions shall be relevant to, and shall arise only in the context of, the preparation of a report to the Dáil and/or Seanad. (3) It shall be an instruction to all Select Committees to which Bills are referred that they shall ensure that not more than two Select Committees shall meet to consider a Bill on any given day, unless the Dáil, after due notice given by the Chairman of the Select Committee, waives this instruction on motion made by the Taoiseach pursuant to Dáil Standing Order 26. The Chairmen of Select Committees shall have responsibility for compliance with this instruction. (4) The Joint Committee shall not consider any matter which is being considered, or of which notice has been given of a proposal to consider, by the Committee of Public Accounts pursuant to Dáil Standing Order 163 and/or the Comptroller and Auditor General (Amendment) Act 1993. (5) The Joint Committee shall refrain from inquiring into in public session or publishing confidential information regarding any matter if so requested, for stated reasons given in writing, by— (a) a member of the Government or a Minister of State, or (b) the principal office-holder of a body under the aegis of a Department or which is partly or wholly funded by the State or established or appointed by a member of the Government or by the Oireachtas: Provided that the Chairman may appeal any such request made to the Ceann Comhairle / Cathaoirleach whose decision shall be final. 35