An Empirical Examination of Arbitrator

advertisement

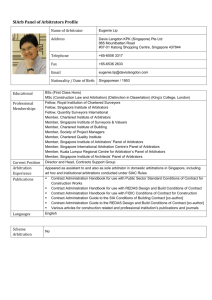

WILLIAM GOLDMAN 10/4/2011 For Educational Use Only THE MORALITY OF CONCILIATION: AN EMPIRICAL..., 16 Harv. Negot. L. Rev. 1 16 Harv. Negot. L. Rev. 1 Harvard Negotiation Law Review Spring 2011 Article THE MORALITY OF CONCILIATION: AN EMPIRICAL EXAMINATION OF ARBITRATOR “ROLE MORALITIES” IN EAST ASIA AND THE WEST Shahla F. Alia1 Copyright (c) 2011 Harvard Negotiation Law Review; Shahla F. Ali Abstract While arbitration is practiced in nearly every region of the world, underlying assumptions of what it means to arbitrate a dispute or to be a “good arbitrator” are largely shaped by notions of role-perception and virtue. Such long standing conceptions tend to be deeply rooted and in turn have a significant influence on contemporary practice. Drawing on the concept of role morality, or the internalized expectations that guide an arbitrator’s actions and constitute a form of implicit law,1 this paper presents a cross-cultural examination of how international arbitrators view their role in actively promoting settlement in the context of international arbitration proceedings. The result of both in-depth interviews as well as a 115-person survey indicate that on the whole, international guidelines such as the UNCITRAL Model Law on International Commercial Arbitration and the IBA Rules of Ethics *2 for International Arbitrators have contributed to the harmonization of contemporary perspectives regarding the appropriateness of particular settlement interventions, such as suggesting settlement negotiations to disputing parties and engaging in settlement negotiations at the request of disputing parties. At the same time, historic and philosophical emphasis on the virtue of reconciliation is reflected in a slightly higher degree of involvement and effectiveness in assisting parties to reach settlement agreements in East Asia than in the West. Because of the flexible structure of international arbitration based on a Model Law system which allows countries to opt in or out of particular provisions, procedural variation pertaining to differing preferences for conciliatory or adjudicatory approaches to arbitration can coexist with a relatively high level of substantive legal uniformity across regions. Overview This article is divided into three parts. Part 1 explores the findings of recent literature regarding how role orientation impacts adjudicatory decision making. Part 2 examines how international guidelines such as the UNCITRAL Model Law on International Commercial Arbitration and the IBA Rules of Ethics for International Arbitrators as well as regional variation in the relative value placed on settlement in the context of international arbitration. This background provides a context for viewing survey findings regarding arbitrator perceptions of their role in promoting settlement. Drawing on the above findings, Part 3 presents survey data regarding how international arbitrators working in East Asian and Western regions view their role in assisting with settlement in international arbitration. The result of both in-depth interviews and a 115-person survey indicate that while traditional notions of role orientation influence perceptions of what constitutes a “virtuous arbitrator,” survey findings indicate that on the whole, arbitrators working in diverse regions have largely congruent perspectives when it comes to their role in promoting settlement in the context of international arbitration. At the same time, arbitrators working in the East Asian region report a slightly more involvement and effectiveness in assisting parties to reach settlement agreements. © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 1 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 10/4/2011 For Educational Use Only THE MORALITY OF CONCILIATION: AN EMPIRICAL..., 16 Harv. Negot. L. Rev. 1 *3 Part 1: An Arbitrator’s Role Orientation Contemporary research in the field of judicial decision-making has shown that there is a direct relationship between an adjudicator’s role orientation and the judicial decision-making process. Originally, the concept of “role moralities” was outlined by Lon Fuller in his work, The Morality of Law. Fuller argued that jurists, like all public officials, must meet certain expectations associated with their roles. These expectations are internalized as a “role morality” that shapes and guides the actions of officials and constitutes a form of implicit law. These “role moralities” are distinct from individual personal moralities in that they provide a standard that applies to the discharge of a distinct social obligation.2 Drawing on this concept of role morality, scholars have examined the impact of role orientation on reflecting a judge’s “beliefs about the criteria which are legitimately a part of decision making.”3 For example, such beliefs may include notions of what constitutes a “virtuous arbitrator” (whether it be placing greater emphasis on reconciling disputing parties or adjudicating between “right and wrong”). Recent research has found that an adjudicators’ role orientation has an impact on judicial behavior. In particular, judges’ attitudes and role orientations “explained 64 percent of . . . sentencing variance, confirming the expectation that values do indeed influence behavior.”4 Such studies also conclude that judges are responsive to the environment in which they work: “when the (perceived) character of the environment changes, so does sentencing behavior.”5 Not only do judicial values influence decision making, but adjudicators also carry certain perceptions of their responsibilities in relation to the treatment of a given case. Such perceptions of role-responsibility in turn influence judicial decision-making procedure.6 While these findings indicate that there is an association between judicial role conceptions and the judicial decision making processes, the literature thus far has focused principally on judges and has been grounded in domestic courts. Little attention has been given to *4 arbitrators and the impact of their perceptions in a transnational commercial dispute resolution context. The Impact of Globalization on Settlement in International Arbitration Practice From a global perspective, two important factors --” convergence” and “informed divergence”--contribute to the development of an arbitrator’s orientation toward his/her role in settlement. International arbitration networks promote convergence based on the norm of “global deliberative equality” and the basic moral precept that “our species is one, and each of the individuals who compose it is entitled to equal moral consideration,”7 However, they can also allow for “informed divergence.”8 In promoting convergence, international arbitration networks “bring together regulators, judges, or legislators to exchange information and to collect and distill best practices.”9 Specifically, arbitrators around the world are “coming together in various ways” and “achieving many of the goals of a formal global legal system: the cross-fertilization of legal cultures in general and solutions to specific legal problems in particular; the strengthening of a set of universal norms regarding judicial independence and the rule of law (however broadly defined).”10 Such “harmonization networks,” Slaughter argues, “exist primarily to create compliance.” Interestingly, “those who would export--not only regulators, but also judges-- may also find themselves importing regulatory styles and techniques, as they learn from those they train. Those who are purportedly on the receiving end may also choose to continue to diverge from the model being purveyed, but do so self-consciously, with an appreciation of their own reasons.”11 This leads to the second principle at work, which is “informed divergence.” This principle allows for diversity within certain boundaries. In describing this principle, Slaughter cites Justice Cardozo: We are not so provincial as to say that every solution of a problem is wrong because we deal with it otherwise at home. The courts are not free to enforce a foreign right at the pleasure of the judges, to suit the individual notion of expediency or fairness. They do not *5 close their doors unless help would violate some fundamental principle of justice, some prevalent conception of good morals, some deep-rooted tradition of the common weal.12 This principle of informed divergence is limited when such solutions or approaches come in conflict with fundamental principles or values. In the case of the United States, this limitation occurs when a law violates the Constitution itself. 13 How arbitrators view their role in settlement in the context of the integration of markets is a new arena for research and practice. Confirming Slaughter’s findings regarding the existence of both “convergence” and “informed divergence” among national legal systems, research in social psychology has found that concepts of individual versus collective identity as well as dialectical versus non-dialectical thinking have influenced unique preferences for adversarial or mediated approaches to dispute resolution.14 Such findings suggest that in order to operate effectively on a global scale, it is important to explore the underlying orientations of parties and arbitrators so that global arbitral frameworks are better equipped to function in an © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 2 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 10/4/2011 For Educational Use Only THE MORALITY OF CONCILIATION: AN EMPIRICAL..., 16 Harv. Negot. L. Rev. 1 increasingly integrated global system.15 Expanding “International Arbitration” Beyond Western Models To date most research on international arbitration and the role of arbitrators in settlement has focused primarily on Western models of arbitration as practiced in Europe and North America. While such studies reflected the geographic foci of international arbitration practice in the mid-20th century, the number of international arbitrations conducted in East Asia has grown steadily and exceeded growth in Western regions in recent years. In 2008, the total number of arbitration cases received by major international arbitration institutions in Western nations--the American Arbitration Association (AAA), the International Chamber of Commerce’s International Court of Arbitration (ICC), the London Court of International Arbitration (LCIA), and the international arbitration centers in Stockholm, Vienna *6 and Vancouver was 1,888. This figure was surpassed by the combined total number of cases received by prominent international arbitration institutions located in East Asia. The China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission (CIETAC), the Beijing Arbitration Commission (BAC), the Japan Commercial Arbitration Association (JCAA), the Hong Kong International Arbitration Centre (HKIAC), the Kuala Lumpur Regional Center for Arbitration (KLRCA), the Singapore International Arbitration Center (SIAC), and the Korean Commercial Arbitration Board (KCAB) collectively received 2,050 cases. 16 Surprisingly, however, few if any studies of international arbitration have included East Asian nations among those surveyed. To represent the emergence of a truly global examination of the practice of arbitration, research on international arbitration must extend to include Asia. To address this gap, this article will examine how arbitration practitioners in East Asia and Western nations view their role in promoting settlement in international arbitration, drawing on the overarching framework of “convergence” and “informed divergence” outlined by Slaughter. Through comparative survey-based research, this article will examine two related questions: 1) Does diversity of culture and worldview give rise to distinct understandings and expectations regarding the role of arbitrators in promoting settlement? 2) Are global economic and legal forces simultaneously harmonizing various approaches to arbitrator involvement in settlement proceedings? A Survey of International Arbitrators The survey used in this study was conducted in 2007. Surveys were distributed to nearly 250 practitioners throughout the world. A total of 115 arbitrators, lawyers and in-house counsel from over 18 countries responded. 17 The participants represented highly experienced practitioners, members of judiciaries, members of arbitration commissions, representatives to UNCITRAL working group meetings - both users and providers of international arbitration. *7 The survey is designed after a survey developed and conducted by Christian Buhring-Uhle between November 1991 and June 1992 and again in 2006.18 Uhle’s study was the first of its kind examining how and why international arbitration cases are settled and the role, if any, that arbitrators play in the settlement process. The survey asked participants in international commercial arbitrations for their perceptions regarding how they view their role in promoting settlements and the way in which amicable settlements are facilitated.19 In his original study, Uhle anticipated that parallel research would be required in countries like those in East Asia. Based on the composition of the sample group, Uhle reports that the findings of his survey must be viewed as representing the “classical,” or “Western-style” practice. He notes that other distinct practices exist, particularly in the Far East, and notes that such practices represent a unique approach to international arbitration, and are particularly important for continued research.20 Thus far, however, no extensive qualitative research study has systematically probed the parallel attitudes of arbitrators working in the East Asian region regarding the practice of international arbitration and the role of arbitrators in settlement. In order to fill this gap, and in particular to determine the existence of variation or harmonization of attitudes and practices among practitioners, the selection of survey questions was re-administered in order to compare responses across regions. The survey sample pool consisted of lawyers, in-house counsel, professors and arbitrators in East Asia. It included members of China’s International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission (CIETAC), members of foreign law firms and © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 3 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 10/4/2011 For Educational Use Only THE MORALITY OF CONCILIATION: AN EMPIRICAL..., 16 Harv. Negot. L. Rev. 1 in-house counsel in China, Malaysia, Singapore, Hong Kong (SAR) and Japan, participants at two regional arbitration conferences held in Malaysia and Hong Kong, and members of a network of arbitrators who are part of the Northern California International Arbitration Forum. In addition, arbitrators from North America and Europe were also surveyed. For purposes of this study, arbitration practitioners are classified according to their primary region of practice. For example, an arbitrator from Germany who has spent the majority of his/her career in East Asia would be regarded as an “East Asian practitioner.” *8 Close to 250 surveys were distributed to arbitrators, attorneys, and in-house counsel and a total of 115 individuals responded. The questions were distributed at arbitration conferences in East Asia, on-line through a web-based survey collection site, and in-person to members of law firms in Beijing, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Japan, and Singapore, and to registered arbitrators listed with two major arbitral institutions in China. Figure 1: Survey Participants TABULAR OR GRAPHIC MATERIAL SET FORTH AT THIS POINT IS NOT DISPLAYABLE In order to supplement the survey findings, open-ended interviews were conducted to examine whether and how diversity and globalization influence the practice of international arbitration in East Asia. 21 Over 64 persons were interviewed between August 2006 and February 2007. The participants were experienced arbitration practitioners, members of judiciaries, members of arbitration commissions, lawyers, in-house counsel, professors, representatives to UNCITRAL, and arbitration users. *9 Principal Findings The result of both the in-depth interviews and the 115-person survey indicate that, while traditional notions of role orientation influence perceptions of what constitutes a “virtuous arbitrator,” international dialogue and collective standard setting play an important role in harmonizing traditionally divergent approaches toward the arbitration process. The survey indicates that on the whole, arbitrators from Eastern and Western regions have largely congruent perspectives when it comes to their role in promoting settlement in the context of international arbitration. At the same time, arbitrators from East Asia report a slightly higher degree of involvement in assisting parties to reach settlement agreements. Because of the flexible structure of the international arbitration system based on a Model Law framework, procedural variation pertaining to differing preferences for conciliatory or adjudicatory approaches to arbitration can coexist with a relatively high level of substantive legal uniformity across regions. Part 2: Harmonization and Diversity: International Guidelines and Regional Orientations This section examines both background international legal guidelines as well as differing preferences for conciliation and litigation in East Asia.22 This background provides a context for viewing survey findings regarding arbitrator perceptions of their role in promoting settlement and perceptions of whether settlement should be a goal of international arbitration. On the one hand, the United Nations Commission on International Trade Law as well as international guidelines such as the IBA Code of Ethics for International Arbitrators have contributed to harmonizing international arbitration procedures. On the other hand, the unique historic roots of dispute resolution in East Asia and the West have given rise to diverse structures and approaches toward the practice of arbitration as well as distinct views on the practice of combining arbitration and conciliation.23 *10 A. Promoting Harmonization: Overview of the UNCITRAL Model Law System and the International Bar Association Rules of Ethics Through the collective efforts of diverse member countries in recent years, two international frameworks have been developed to harmonize approaches toward the resolution of international disputes: the UN Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) Model Law on International Commercial Arbitration, and the International Bar Associations’ Rules of Ethics for International Arbitrators. © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 4 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 10/4/2011 For Educational Use Only THE MORALITY OF CONCILIATION: AN EMPIRICAL..., 16 Harv. Negot. L. Rev. 1 UNCITRAL Model Arbitration Law In an effort to provide a forum for discussing and harmonizing diverse institutional approaches to the practice of arbitration across the globe, the United Nations established the UN Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL). UNCITRAL was established by the General Assembly in 1966.24 According to UN archival documents pre-dating the formation of UNCITRAL, the General Assembly created the body out of the recognition that disparities in national laws governing international trade created obstacles to the flow of trade, and it saw the Commission as the means by which the United Nations could play a more active role in reducing or removing these obstacles. 25 The General Assembly gave the Commission an overarching mandate to further harmonize and unify international trade laws.26 Since its founding, UNCITRAL has prepared a wide range of conventions, Model Laws, and other instruments dealing with the substantive law that governs trade transactions or other aspects of business law having an impact on international trade.27 According to the Commission, “‘harmonization’ may conceptually be thought of as the process through which domestic laws may be modified to enhance predictability in cross-border commercial transactions.”28 UNCITRAL uses Model Laws or legislative guides to harmonize domestic laws amongst different countries. *11 The UNCITRAL Commission is composed of sixty member States elected by the General Assembly. 29 Membership on the Commission is “structured so as to be representative of the world’s various geographic regions and its principal economic and legal systems.”30 There are five regional groups represented within the Commission: African States, Asian States, Eastern European States, Latin American and Caribbean States, and Western European and Other States. Members of the Commission are elected for terms of six years, with the terms of half the members expiring every three years. 31 Recognizing the need for greater uniformity of arbitration and conciliation practices, in 1998 the UNCITRAL secretariat suggested that a working group be created to draft a Model Law on Conciliation.32 The principal legal officer stated, “UNCITRAL places dispute settlement as its highest priority.”33 During the drafting process, the UNCITRAL forum provided space for wide-ranging discussion of diverse perspectives. The Chinese representative to the UNCITRAL working group meetings for the Model Law on Conciliation noted that “a heated topic at the UNCITRAL working group sessions was whether the arbitrator can act as a conciliator. Some say that this is a good process and that it works well in such countries as Singapore, China, Hong Kong, and *12 Stockholm [sic] - if the parties agree to it.”34 He added that “many other countries say no, particularly the US and Mexico. They say that the role of the arbitrator and the mediator is different. The mediator assists parties to reach an agreement. . . Arbitrators on the other hand just decide the dispute. If some information is shared during mediation, this could affect the arbitration.”35 While ultimately the Model Law did not provide a role for an arbitrator to act as a conciliator, the process provided space for global dialogue on the topic. One participant noted that the decision making is based on consensus and that “[t]hrough the exchange of views we can increase. . . understanding.”36 The Chinese drafting team did not incorporate the provision of the Model Law restricting the arbitrators’ ability to act simultaneously as a mediator, but it did include a number of other significant provisions from the Model Law pertaining to pre-hearing directives, the selection and appointment of the arbitrator, the procedure for filing claims and counterclaims, the procedure for issuing awards, and the time frame for award challenges.37 International Bar Association’s Rules of Ethics for International Arbitrators Similar to the aim of the UNCITRAL Model Arbitration Law, the International Bar Association’s suggested Rules of Ethics for International Arbitrators was developed in order to facilitate international agreement on the rules of ethics for international arbitrators.38 These model rules provide that “International arbitrators should be impartial, independent, competent, diligent and discreet.”39 The rules themselves “seek to establish the manner in which these abstract qualities may be assessed in practice.”40 Rather than rigid rules, they reflect “guidelines developed by practicing lawyers from all continents.”41 *13 The rules themselves operate through the agreement of the parties. The most fundamental rule adopted by the code of ethics is that “arbitrators shall proceed diligently and efficiently to provide the parties with a just and effective resolution of their disputes, and shall remain free from bias.”42 With respect to the involvement of arbitrators in settlement proposals, the model rules provide a middle ground. On the one hand, the rules provide space for arbitrators to participate in settlement discussions at the agreement of parties, but at the same time, they encourage such settlement discussions to be conducted in joint session. 43 © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 5 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 10/4/2011 For Educational Use Only THE MORALITY OF CONCILIATION: AN EMPIRICAL..., 16 Harv. Negot. L. Rev. 1 Discussion Both the UN Model Law and IBA rules of ethics provide guidelines for arbitrator involvement in settlement practices. These guidelines present standards of neutrality, impartiality and competence. At the same time, such models allow countries to opt in or out of particular provisions, including those pertaining to whether an arbitrator can actively participate in mediated settlement discussions during the course of the arbitration. Because of this flexible approach, procedural variation pertaining to differing preferences for conciliatory or adjudicatory approaches to arbitration can coexist with a relatively high level of substantive legal uniformity across regions. B. Legal Diversity: Underlying Cultural Roots of Arbitration in East Asia In recent years, while the process of harmonization has increasingly unified global legal standards, the contributions of diverse national legal systems have simultaneously enriched them. Uhle notes that “different traditions exist with respect to the concept of arbitration. . . Accordingly the concept of arbitration varies with the personalities of arbitrators and is often influenced by their cultural background.”44 The next section will examine, in particular, the *14 unique contribution of East Asian legal thought to the role of the arbitrator in the resolution of disputes. Traditional Concept of Arbitrator Role-Morality in East Asia From a historical perspective, the traditional role-morality of the arbitrator in East Asia is influenced by two important Confucian principles: 1) li, the preservation of virtue and natural harmony, and 2) jiang, compromise in order to reach settlement.45 In practice, Confucian philosophy viewed “li” or the preservation of relations through virtuous deeds as a higher expression of righteousness than merely following a set of legal sanctions. 46 In the Analects, the original writings of Confucius, this distinction is made clear: The people should be positively motivated by li, to do that which they ought; if they are intimidated by fear of punishment they will merely strive to avoid the punishment, but will not be made good. To render justice in lawsuits is all very well, but the important thing, Confucius said, is to bring about a condition in which there will be no lawsuits.47 Similarly, the principle of “jiang,” or compromise, was also emphasized by Confucian family and clan groups. A Ming dynasty set of “Family Instructions” established by the Miu lineage in Guandong province contained admonitions on resolving conflict through a process of introspection, tolerance, and forgiveness: If one gets into fights with others, one should look into oneself to find the blame. It is better to be wronged than to wrong others. . . Even if the other party is unbearably unreasonable; one should contemplate the fact that the ancient sages had to endure much more. If one remains tolerant and forgiving, one will be able to curb the other party’s violence. 48 Based on the principles of “li” and “jiang”, arbitrators commonly emphasized conciliation through compromise as a goal of the dispute resolution process. The virtue of compromise was often central to the achievement of agreement between parties. The following record of the resolution of a family dispute in Taitou, Shantung province by a *15 local team of “peacemakers” gives us a picture of the process that took place: First, the invited or self-appointed village leaders come to the involved parities to find out the real issues at stake, and also to collect opinions from other villagers concerning the background of the matter. Then they evaluate the case according to their past experience and propose a solution. In bringing the two parties to accept the proposal, the peacemakers have to go back and forth until the opponents are willing to meet half way. Then a formal party is held either in the village or in the market town, to which are invited the mediators, the village leaders, clan heads, and the heads of the two disputing families. The main feature of the party is a feast. While it is in progress, the talk may concern anything except the conflict. . . If the controversy is settled in a form of “negotiated peace,” that is, both parties admit their mistakes, the expenses will be equally shared. . . thus the conflict is resolved.49 A “virtuous” arbitrator was one who had the ability to conciliate and encourage resolution among disputing parties. Accounts of individuals such as Zhu Jiefu, an early Confucian scholar and later a merchant of the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), illustrate the traditional emphasis placed on private third-party conciliation, the importance of adjudicator integrity, the fluid integration of mediation and arbitration, and the use of “indirect persuasion” in order to encourage settlement in the context of early Confucian dispute resolution practice. In his biography, it was recorded that Jiefu, “being lofty and righteous” was able to bring about the resolution of disputes: © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 6 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 10/4/2011 For Educational Use Only THE MORALITY OF CONCILIATION: AN EMPIRICAL..., 16 Harv. Negot. L. Rev. 1 When there was a dispute among the merchants. . . Jiefu would always promptly mediate it. Even when one group would go to his house and demand his compliance with their views; he would still be able to settle the dispute by indirect and gentle persuasion. Hence, people both far and near came one after the other to ask him to be their arbitrator.50 In recent years, continued encouragement of the facilitation of agreement among disputing parties has evolved and developed within countries in the East Asian region. Particular arbitral institutions such as the China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission, the Hong Kong International Arbitration Commission *16 and the Japan Arbitration Commission permit an arbitrator to encourage settlement through conciliation attempts, both with the consent of the disputing parties and within the context of arbitration proceedings. At the same time, some arbitral institutions in the region, such as the Beijing Arbitration Commission, permit parties to request the replacement of an arbitrator-turned-mediator, if the parties have concerns about impartiality.51 Discussion Background on international legal guidelines as well as historic approaches to the integration of conciliation and adjudication provides a context for viewing survey findings regarding arbitrator perceptions of their role in promoting settlement as discussed below. Part III. Perspectives on the Appropriateness and Role of the Arbitrators in Promoting Settlement In the context of the recent development of international model arbitration laws as well as regional variation in the relative value placed on settlement, this next section seeks to examine how contemporary arbitrators view their role in promoting settlement in international arbitration.52 The survey questions used in this study of 115 arbitration practitioners working both in the East Asian and Western regions aimed to examine what contemporary arbitrators do to facilitate amicable solutions, how often these techniques are employed, and whether these methods are appropriate in the arbitrators’ own opinions. 53 Such questions touch on both the appropriateness and practice of arbitrator involvement in settlement and largely invoke notions of arbitrator role morality and what it means to be a good arbitrator.54 The survey offered six suggested techniques as follows: • Suggesting settlement negotiations to the parties • Actively participating in settlement negotiations (at both parties’ request) • Meeting with the parties separately to discuss settlement options (with both parties’ consent) *17 • Hinting at the possible outcome of the arbitration (without being asked to do so) • Rendering a “case evaluation” to the parties (at both parties’ request) • Proposing a settlement formula (at both parties’ request) 55 On the one hand, the survey findings indicate that international guidelines have contributed to harmonizing the perspectives of international arbitrators as to the appropriateness of the settlement interventions described above.56 For example, all arbitrators surveyed shared the view that it is appropriate to suggest settlement negotiations to parties and actively participate in settlement negotiation at parties’ request. Arbitrators also shared the view that certain interventions, such as hinting at the possible outcome of a case, were generally not appropriate. At the same time, while perspectives on the appropriateness of settlement interventions reflect a largely harmonized perspective, with respect to the actual role of the arbitrator in facilitating a settlement, the survey findings indicate that regional variation exists, revealing a slightly higher proclivity on the part of arbitrators working in the East Asian region to encourage a settlement. Appropriateness of Arbitrator Involvement The survey sought to examine practitioners’ attitudes concerning the appropriateness of arbitrator involvement in settlement.57 In general, the findings indicate that international guidelines have helped harmonize the perspectives of © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 7 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 10/4/2011 For Educational Use Only THE MORALITY OF CONCILIATION: AN EMPIRICAL..., 16 Harv. Negot. L. Rev. 1 international arbitrators as to the appropriateness of the settlement interventions described above. 58 For example, most arbitrators surveyed in both regions, in conformity with international guidelines, shared the view that it is appropriate to suggest settlement negotiations to parties and to be an active participant in settlement negotiation at parties’ request. Arbitrators also shared the view that certain interventions were generally not appropriate, such as hinting at the possible outcome of a case to the parties. Below is a discussion of the findings in this regard: *18 Summary Table 1: The Role of Settlement in Arbitration Proceedings - Answering “Yes” by Region of Practice (%), 2006/7 Questions Is it appropriate for the arbitrator to suggest settlement negotiations to the parties? Is it appropriate for the arbitrator to actively engage in settlement negotiations (at both parties request)? Is it appropriate for the arbitrator to meet with parties separately to discuss settlement options (with both parties request)? Is it appropriate for the arbitrator to hint at the possible outcome of the arbitration (without being asked to do so)? Is it appropriate for the arbitrator to render a “case evaluation” to the parties (at both parties request)? Is it appropriate for the arbitrator to propose a settlement formula (at both parties request)? Is it appropriate for an arbitration institution, at its own initiative, to suggest the use of mediation to parties? * Notes: *Difference is statistically significant according to Chi-square analysis. Responding “Yes” Region of Practice East West 74% 73% 58% 58% 43% 38% 35% 24% 36% 46% 51% 58% 68% 92% In general, arbitration practitioners working in both East Asia and Western regions reported relatively similar levels of approval for selected settlement techniques. *19 Table 2: Perception of Appropriateness of Arbitrator to Actively Engage in Settlement Negotiations (at Both Parties’ Request) by Region of Practice (%), 2006/7 Region of Practice East West 58% 58% 42% 42% 100% 100% (77) (26) Notes: * Difference is not statistically significant according to Chi-square analysis: Pearson’s chi-square = 0.0044 (p < 1). Response* Yes No Total The survey asked practitioners whether it was appropriate for the arbitrator to actively engage in settlement negotiations at both parties’ request. An equal proportion of practitioners working in East Asia and Western regions viewed it as appropriate for the arbitrator to actively engage in settlement negotiations at both parties’ request. Nearly 58% of practitioners working in both East Asia and the West felt that once parties requested it, it was appropriate to actively engage in settlement. Table 3: Perception of Appropriateness of Arbitrator Meeting with Parties Separately to Discuss Settlement Options (at Both Parties’ Request) by Region of Practice (%), 2006/7 Response* Yes East 43% Region of Practice West 38% © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 8 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 10/4/2011 For Educational Use Only THE MORALITY OF CONCILIATION: AN EMPIRICAL..., 16 Harv. Negot. L. Rev. 1 No Total 57% 62% 100% 100% (77) (26) Notes: * Difference is not statistically significant according to Chi-square analysis: Pearson’s chi-square = 0.15 (p < 1). Similarly, a nearly equal proportion of practitioners working in East Asia viewed it as appropriate for the arbitrator to meet with parties separately to discuss settlement options at both parties’ request. Nearly 43% of practitioners in East Asia and 38% of practitioners working in Europe and America viewed this as appropriate. Describing this process, one arbitrator shared: *20 At the very end of the first hearing an arbitrator will ask if we would like to mediate. If they agree we arrange a second meeting for the mediation. We have separate rooms; three arbitrators will all participate in the mediation. We have informal discussions. We don’t discuss the legal issues. It is more like a bargaining session. It is very flexible and something that people are very open to. The parties also benefit because they have authority to make decisions. Often we do not ask them to say too much. We just meet together in private.59 Table 4: Perception of Appropriateness of Arbitrator Proposing a Settlement Formula (at Both Parties’ Request) by Region of Practice (%), 2006/7 Region of Practice East West 51% 58% 49 42 100% 100% (76) (26) Notes: * Difference is not statistically significant according to Chi-square analysis: Pearson’s chi-square = 0.31 (p < 1). With regard to the appropriateness of the arbitrator proposing a settlement formula at both parties’ request, a relatively equal proportion of arbitrators working in Western (58%) and East Asian regions (51%) surveyed saw this as appropriate. One arbitrator working in China noted that after hearing the background on a case “[the arbitrator] can suggest or propose a good settlement that will work for both sides. In mediation, it is under the condition that the parties agree.”60 Response* Yes No Total *21 Table 5: Perception of Appropriateness of Arbitrator Rendering a “Case Evaluation” to the Parties (at Both Parties’ Request) by Region of Practice (%), 2006/7 Region of Practice East West 36% 46% 64 54 100% 100% (75) (26) Notes: * Difference is not statistically significant according to Chi-square analysis: Pearson’s chi-square = 0.83 (p < 1). Response Yes No Total Similarly, in response to the question of whether it is appropriate for the arbitrator to render a “case evaluation” for the parties at both parties’ request, only 46% of practitioners working in the West and 36% of practitioners working in East Asian viewed this as appropriate. The convergence of perspective reflected in these survey findings appears to reflect international guidelines such as the IBA Rules of Ethics regarding the importance of arbitrator neutrality. Table 6: Perception of Appropriateness of Arbitrator Hinting at the Possible Outcome of the Arbitration (Without Being Asked to Do So) by Region of Practice (%), 2006/7 Response* Yes No Total East 35% 65 100% Region of Practice West 24% 76 100% © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 9 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 10/4/2011 For Educational Use Only THE MORALITY OF CONCILIATION: AN EMPIRICAL..., 16 Harv. Negot. L. Rev. 1 (77) (25) Notes: * Difference is not statistically significant according to Chi-square analysis: Pearson’s chi-square = 1.055 (p < 1). Particular arbitrator interventions were viewed by the majority of all practitioners surveyed as inappropriate. The majority of all those surveyed did not view it as appropriate for the arbitrator to hint at the possible outcome of the arbitration without being asked to do so. Only 24% of practitioners working in Europe and America and 35% of practitioners working in East Asian felt this was appropriate. Many *22 arbitrators interviewed saw this type of approach as harming arbitral integrity. Discussion International guidelines may be at least in part responsible for the common views between East Asian and Western practitioners described above.61 For example, all arbitrators surveyed shared the view that it is appropriate to suggest settlement negotiations to parties and to actively participate in settlement negotiation at parties’ request. Arbitrators also shared the view that certain interventions were generally not appropriate such as hinting at the possible outcome of a case. Actual Participation of Arbitrators in Facilitating Settlement Building on the findings reported in the previous section regarding perceptions of the appropriateness of particular arbitrator interventions, the next set of survey questions looked to the actual role of the arbitrator in facilitating settlement. The data shows both harmonization and regional variation in relation to reported levels of actual participation in arbitrator interventions. Arbitrators from all regions generally do not hint at the possible outcome of a case or render case evaluations. At the same time, regional variation in survey responses indicates a greater inclination on the part of arbitrators working in the East Asian region to facilitate particular settlement interventions. This is achieved through suggesting settlement negotiations to the parties, actively participating in settlement negotiations (at both parties’ request), meeting with the parties separately to discuss settlement options (with both parties’ consent), and proposing a settlement formula (at both parties’ request).62 On average, the frequency among practitioners working in East Asia in using these techniques was more than double that reported by counterparts working in Europe and America. The following table summarizes the percentages of arbitrators surveyed working in the East Asian and Western regions who “almost always” or “often” participated in settlement through the use of various techniques described below63: *23 Table 7- Summary Table: The Role of Arbitrators in the Settlement Process - Answering “Almost Always” or “Often” by Region of Practice (%), 2006/7 Response - Almost Always/Often By suggesting settlement negotiations to the parties * By actively engaging in settlement negotiations (at both parties request)? By meeting with parties separately to discuss settlement options (with both parties request)? By hinting at the possible outcome of the arbitration (without being asked to do so)? By rendering a “case evaluation” to the parties (at both parties request)? By proposing a settlement formula (at both parties request)? Notes: * Difference is statistically significant according to Chi-square analysis. East 40% 30% 26% 4% 10% 17% Region of Practice West 16% 16% 8% 8% 8% 4% Harmonization A significant degree of harmonization is reflected with respect to the practitioner’s reported engagement in particular practices, such as hinting at the possible outcome of a case and rendering case evaluations. 64 Techniques that were used either sometimes or practically never, in all regions, were rendering a “case evaluation” for the parties (at both parties request). Practitioners reported that these techniques were used almost always or often only between 8% and 10% of the time. *24 Table 8: Frequency of Arbitrator Involvement in Settlement by Rendering a Case Evaluation to the Parties (at Both Parties’ Request) by Region of Practice (%), 2006/7 © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 10 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 10/4/2011 For Educational Use Only THE MORALITY OF CONCILIATION: AN EMPIRICAL..., 16 Harv. Negot. L. Rev. 1 Region of Practice East West 10% 8% 90% 92% 100% 100% (72) (24) Notes: * Difference is not statistically significant according to Chi-square analysis: Pearson’s chi-square = 0.40 (p < 1). Response* Almost always/Often Rarely Total The technique used least frequently in all regions was hinting at the possible outcome of the arbitration (without being asked to do so). On average this technique was reported to be used “rarely” or “practically never” by a majority of the respondents (96%) who likewise considered the practice inappropriate. Table 9: Frequency of Arbitrator Involvement in Settlement by Hinting at the Possible Outcome of the Arbitration (without Being Asked to Do So) by Region of Practice (%), 2006/7 Region of Practice East West 4% 8% 96% 92% 100% 100% (72) (24) Notes: * Difference is not statistically significant according to Chi-square analysis: Pearson’s chi-square = 0.63 (p < 1). Response* Almost always/Often Rarely Total Regional Variation While the shared agreement regarding the inappropriateness of hinting at the possible outcome of a case or rendering a case evaluation reflects a harmonization of views, the most significant variation in survey findings was found with respect to the active role that arbitrators working in the East Asian region reported playing in promoting settlement among parties. The arbitrators played that role through suggesting settlement negotiations to the parties, actively participating in settlement negotiations (at both parties’ request), *25 meeting with the parties separately to discuss settlement options (with both parties’ consent), and proposing a settlement formula (at both parties’ request). Table 10: Frequency of Arbitrator Involvement in Settlement by Suggesting Settlement Negotiations to the Parties by Region of Practice (%), 2006/7 Region of Practice East West 40% 16% 60% 84% 100% 100% (72) (24) Notes: * Difference is statistically significant according to Chi-square analysis: Pearson’s chi-square = 4.44 (p < 0.05). Response* Almost always/Often Rarely Total More than 40% of practitioners working in East Asia report regularly suggesting settlement negotiations to the parties, in comparison with 16% of counterparts working in the West. This variation was found to be statistically significant. Reflecting an ethic of social responsibility associated with the promotion of settlement, a Chinese arbitrator shared that “arbitrators must be organized and must consider how they can cut costs and must have a sense of social responsibility to the parties.”65 With regard to suggesting the use of mediation to parties, an arbitrator working in China described the importance of receptivity to the approach. He noted that “doing mediation entirely depends on the parties” and their willingness to engage in the process.66 Describing the usefulness of such an approach, a representative to the UNCITRAL working group noted that “in many cases there really is a gray area” for which a more flexible approach is required. 67 The primary concern is that the final outcome of the arbitration is fair. *26 Table 11: Frequency of Arbitrator Involvement in Settlement by Actively Participating in Settlement Negotiations © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 11 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 10/4/2011 For Educational Use Only THE MORALITY OF CONCILIATION: AN EMPIRICAL..., 16 Harv. Negot. L. Rev. 1 (at Both Parties’ Request) by Region of Practice (%), 2006/7 Region of Practice East West 30% 16% 70% 84% 100% 100% (72) (24) Notes: * Difference is not statistically significant according to Chi-square analysis: Pearson’s chi-square = 1.75 (p < 0.20). Similarly, over 30% of practitioners working in East Asia reported regularly participating in settlement negations in comparison with 16% of those surveyed working in Europe and America. One arbitrator working in China noted that arbitrators will “come to the arbitration with many questions to ask the parties.”68 The purpose of this fact-gathering process is to help the parties to settle. Another arbitrator explained that “in certain areas the parties have a right position and a wrong position. You can’t say that one party is 100% right or the other is 100% wrong. The arbitration panel. . . [will] point. . . out the positive and negative side of each of the parties’ case. [Each party] knows deep down that [it] d[oes] not have 100% right on [its] side. . . Finally, we [will] reach a settlement.”69 Response* Almost always/Often Rarely Total Table 12: Frequency of Arbitrator Involvement in Settlement by Meeting with the Parties Separately to Discuss Settlement Options (with Both Parties’ Consent) by Region of Practice (%), 2006/7 Region of Practice East West 26% 8% 74% 925 100% 100% (71) (24) Notes: * Difference is not statistically significant according to Chi-square analysis: Pearson’s chi-square = 3.12 (p< 0.10). Response* Almost always/Often Rarely Total *27 Meeting separately with parties to discuss settlement is also a technique used with more relative frequency by practitioners working in East Asia (26%) than their counterparts working in the West (8%). An arbitrator described this process as follows: At first we hear both parties’ arguments, read their documents and ask questions. We then have a small meeting with the other arbitrators to see if we can conciliate. If so, we ask the parties whether they will accept our agreement to conciliate. If not, then we will issue an award. During the mediation we don’t take a record of notes. We meet separately with the parties. We tell them, these are your correct points, and these are the areas where you are wrong. At least you must give them this much. We do the same with the other party. This helps parties realize they may not have 100% case. Then they can be more open to thinking of an amount that will reflect a compromise.70 Table 13: Frequency of Arbitrator Involvement in Settlement by Proposing a Settlement Formula (at Both Parties’ Request) by Region of Practice (%), 2006/7 Region of Practice East West 17% 4% 83% 96% 100% 100% (72) (23) Notes: * Difference is not statistically significant according to Chi-square analysis: Pearson’s chi-square = 2.23 (p < 0.20). In addition to meeting separately with parties, 17% of practitioners working in the East Asian region reported regularly suggesting a settlement formula in comparison with 4% of practitioners surveyed working in Europe and North America. A member of a Chinese arbitral institution noted that “after parties have a general view and hear the claims and evidence of both parties they know where the essential points are. Then they can suggest or propose a good settlement that will work for both sides. In mediation, it is under the condition that the parties agree.”71 An arbitrator working in China *28 added that a critical capacity of a good arbitrator is that he/she “should have some skill to give suggestions.”72 Response* Almost always/Often Rarely Total © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 12 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 10/4/2011 For Educational Use Only THE MORALITY OF CONCILIATION: AN EMPIRICAL..., 16 Harv. Negot. L. Rev. 1 One arbitrator working in the East Asian region shared the benefits of integrating mediated settlement discussions into the arbitration proceedings: In the hearing, only law and facts are considered. But in mediation, we can hear what is behind the law and facts, and get to the motives. For example, one joint venture wanted to terminate a contract. But what they really wanted to do was to take the resources and move them to another site. The claim was really only a tiny part of the real issue. The mediation was a good way for the arbitrators to get more information. . . .I think mediation generally speaking is more helpful - at least it is not harmful. It will help all sides to discover the facts.73 While arbitrators acknowledged that they might be exposed to information not generally disclosed in an arbitral hearing during a mediation attempt, several noted that such information ultimately helps in drafting a better award. A CIETAC staff member noted that “some say it is unfair because through mediation the arbitrator will know something that he/she wouldn’t in an arbitration hearing; however, parties can chose what they wish to disclose. This just helps the arbitrator come to a more informed and better outcome based on facts.”74 Another arbitrator noted that the “arbitrator already knows the major issues in the case and [mediation gives him] a better understanding of the positions, the facts and circumstances of the case.”75 This view was expanded upon by an arbitrator working in Beijing: The arbitrator gets to know the background, the context, the motives and the issues involved in each case so that we can better resolve the issues rather than a narrow view. This helps to avoid simply an award that is based on legal concepts and views.76 Several interviewees stressed the fact that mediation in the context of arbitration is not mandatory in East Asia. Parties are given the option at the outset. An attorney working in the region noted that “after the parties are at loggerheads, they want to have their day in *29 court. It is not compulsory to have conciliation.”77 An arbitrator who has done extensive arbitration work in China explained, “CIETAC arbitrators do not push mediation. If the parties don’t want to mediate they won’t approach it. If after the initiation of mediation you see that it isn’t making progress, we switch out of mediation and go back into arbitration. It is not like Western mediation, which is a formal process.”78 Discussion On the one hand, the survey findings indicate that international guidelines have contributed to harmonizing the perspectives of international arbitrators as to the appropriateness of settlement interventions. 79 For example, all arbitrators surveyed shared the view that it is appropriate to suggest settlement negotiations to parties and to participate actively in settlement negotiation when the parties request it. Arbitrators also shared the view that certain interventions were generally not appropriate (e.g. hinting at the possible outcome of a case). At the same time, the survey findings indicate that while perspectives on the appropriateness of settlement interventions are largely harmonized, with respect to the actual role of the arbitrator in facilitating settlement, regional variation exists with a greater proclivity on the part of arbitrators working in the East Asian region to facilitate a particular settlement. In essence, arbitrators agree on principles of settlement intervention, but apply these principles in unique ways across regions. This can perhaps be linked to unique historical and social contexts giving rise to a stronger orientation on the part of arbitrators and disputing parties working in the region as to the importance of reconciliation and openness to settlement interventions. Conclusion The result of both in-depth interviews as well as the 115-person survey indicate that while traditional notions of role orientation influence perceptions of what constitutes a “virtuous arbitrator” in relation to settlement ability and degree of intervention, arbitrators working in Eastern and Western regions have largely congruent *30 perspectives when it comes to the parameters of their role in promoting settlement in the context of international arbitration. In responding to recent observations that legal study must be underpinned by theorizing that treats generalizations across legal families, traditions, cultures, and orders as problematic, 80 this paper examined those underlying norms that guide dispute resolution processes and shape an arbitrators notion of his/her “role morality.”81 While arbitration is practiced in nearly every region of the world, underlying assumptions of what it means to arbitrate a dispute or to be a “good arbitrator” are partly shaped by notions of role-perception and virtue. Such long standing conceptions tend to be deeply-rooted and in turn have a significant influence on contemporary practice. At the same time, international commercial exchange has given rise to increasingly harmonized practices in relation to arbitrator perceptions of the appropriateness of selected settlement © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 13 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 10/4/2011 For Educational Use Only THE MORALITY OF CONCILIATION: AN EMPIRICAL..., 16 Harv. Negot. L. Rev. 1 interventions. In general, the findings from the interviews and survey questions bear out the central hypothesis. Regional variation in the relative value placed on settlement and relationship preservation is reflected in differing levels of emphasis placed on the role of the arbitrator in settlement. In contrast, a lower level of variation and hence greater harmonization of perspectives was found in relation to aspects of arbitration touching on international principles of arbitrator neutrality rooted in international norms and guidelines. The principal finding of this paper is that because of the flexible structure of international arbitration based on a Model Law system, procedural variation pertaining to differing preferences for conciliatory or adjudicatory approaches to arbitration can coexist with a relatively high level of substantive legal uniformity across regions. Footnotes a1 Assistant professor and Deputy Director, LLM Program in Arbitration and Dispute Resolution, Faculty of Law, University of Hong Kong. B.A., Stanford University; M.A., Landegg International University, Switzerland; J.D., Boalt Hall School of Law, University of California at Berkeley; Ph.D, University of California at Berkeley. The author wishes to thank the University of Hong Kong Research Committee for its kind support of this project. Special thanks also to Victor Ali for his helpful comments and support. The author also wishes to thank the many arbitration practitioners, attorneys and members of the legal profession in East Asia, North America and Europe who participated in shaping and responding to the empirical research. The interviews, which were completed with the promise of anonymity for the interviewees, are on file with the author. The author’s interview numbers have been retained for ease of reference. 1 See Lon L. Fuller, the morality of law (rev. ed. 1969). 2 See id. 3 James L. Gibson, Environmental Constraints on the Behavior of Judges: A Representational Model of Judicial Decision Making, 14 Law & Soc’y Rev. 343, 363 (1979-80). 4 Id. at 354. 5 Id. at 360. 6 See V. Lee Hamilton & Joseph Sanders, Everyday Justice (1992). 7 Anne Marie Slaughter, A New World Order 11 (2004) 245. 8 Id. at 11. 9 Id. at 19. 10 Id. at 102. 11 Id. at 172. 12 Id. at 247. © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 14 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 10/4/2011 For Educational Use Only THE MORALITY OF CONCILIATION: AN EMPIRICAL..., 16 Harv. Negot. L. Rev. 1 13 See id. at 248. 14 Kaiping Peng, Situated Legal Thoughts: How Culture Affects How We Think About Law and Business (2007) (unpublished manuscript, on file with the author). 15 See also Shahla Ali, Barricades and Checkered Flags: Comparing Views on Roadblocks and Facilitators of Settlement Among Arbitration Practitioners in East Asia and the West, 19 Pac. Rim L. & Pol’y J. 243 (2010). 16 It must be noted that data from both the International Chamber of Commerce and the China International Economic and Trade Arbitration Commission combined domestic and international cases in their totals for 2005. 17 For a full discussion, see Shahla F. Ali, Resolving Disputes in the Asia-Pacific: International Arbitration and Mediation in East Asia and the West (2010). 18 See Christian Buhring-Uhle, Arbitration and Mediation in International Business (2d ed. 2006). 19 Id. 20 Id. at 131 21 See Rhett Diessner, Action Research, Converging Realities 1:1 (2000), available at http://bahai-library.com/?file=diessner_action_ research.html. A principle orientation of the research process employed here is an emphasis on participation from those immediately and substantially affected by the potential outcome of the research. Participants were given a voice in framing and reframing the interview question under study, a voice in selecting the means of answering the question defined by the research, and a voice in determining the criteria to decide whether the question has been validly answered. Id. 22 See generallyShahla F. Ali,Approaching the Global Arbitration Table: Comparing the Advantages of Arbitration as Seen by Practitioners in East Asia and the West, 28Rev. Litig.791 (2009). 23 See generally Gabriel Kaufmann-Kohler & Fan Kun,Integrating Mediation into Arbitration: Why it Works in China, 25J. Int’l Arb. 479 (2008). 24 SeeG.A. Res. 2205 (XXI), U.N. Doc. A/RES/2205(XXI) (Dec. 17, 1966). 25 See United Nations Comm’n on Int’l Trade Law [hereinafter UNCITRAL], http://www.uncitral.org/uncitral/en/about/origin.html (last visited Sept. 30, 2010). 26 Id. 27 Id. © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 15 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 10/4/2011 For Educational Use Only THE MORALITY OF CONCILIATION: AN EMPIRICAL..., 16 Harv. Negot. L. Rev. 1 28 Id. 29 Id. As of June 14, 2004, the members of UNCITRAL, and the years when their memberships expire, are: Algeria (2010), Guatemala (2010), Russian Federation (2007), Argentina (2007), India (2010), Rwanda (2007), Australia (2010), Iran (Islamic Republic of) (2010), Serbia (2010), Austria (2010), Israel (2010), Sierra Leone (2007), Belarus (2010), Italy (2010), Singapore (2007), Belgium (2007), Japan (2007), South Africa (2007), Benin (2007), Jordan (2007), Spain (2010), Brazil (2007), Kenya (2010), Sri Lanka (2007), Cameroon (2007), Lebanon (2010), Sweden (2007), Canada (2007), Lithuania (2007), Switzerland (2010), Chile (2007), Madagascar (2010), Thailand (2010), China (2007), Mexico (2007), The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (2007), Colombia (2010), Mongolia (2010), Tunisia (2007), Croatia (2007), Morocco (2007), Turkey (2007), Czech Republic (2010), Nigeria (2010), Uganda (2010), Ecuador (2010), Pakistan (2010), United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland (2007), Fiji (2010), Paraguay (2010), United States of America (2010), France (2007), Poland (2010), Uruguay (2007), Gabon (2010), Qatar (2007), Venezuela (Bolivarian Republic)(2010), Germany (2007), Republic of Korea (2007), Zimbabwe (2010). 30 Id. 31 Id. 32 SeeProvisional Agenda, Comm’n on Int’l Trade Law, 32d Sess. Working Group on Arbitration (1999), U.N. Doc. A/CN.9/WG.II/WP.107 (Jan. 17, 2000); U.N. Secretary-General, Settlement of Commercial Disputes, Comm’n on Int’l Trade Law, 32d Sess. Working Group on Arbitration (1999) U.N. Doc. A/CN.9/WG.II/WP.108 (Jan. 14, 2000). 33 Interview No. 1 with Principle Legal Officer, UNCITRAL, in Kuala Lumpur, Malay. (Nov. 22, 2006). 34 Interview No. 3 with East Asian Arbitrator, Chinese Representative to UNCITRAL, in Kuala Lumpur, Malay. (Nov. 22, 2006). 35 Id. 36 Id. 37 Id. 38 See Int’l Bar Ass’n, Rules of Ethics for International http://www.ibanet.org/images/downloads/pubs/Ethics_ arbitrators.pdf. 39 Id. 40 Id. 41 Id. 42 Id. Arbitrators © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. (2008), available at 16 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 10/4/2011 For Educational Use Only THE MORALITY OF CONCILIATION: AN EMPIRICAL..., 16 Harv. Negot. L. Rev. 1 43 Id. at 4. The rules state: “Where the parties have so requested, or consented to a suggestion to this effect by the arbitral tribunal, the tribunal as a whole (or the presiding arbitrator where appropriate), may make proposals for settlement to both parties simultaneously, and preferably in the presence of each other.” 44 Buhring-Uhle, supra note 18, at 162; see also Kaufmann-Kohler & Kun, supra note 23 (discussing the impact of culture on arbitration). 45 Michael T. Colatrella, Jr., “Court-Performed” Mediation in the People’s Republic of China: A Proposed Model to Improve the United States Federal District Courts’ Mediation Programs, 15 Ohio St. J. on Disp. Resol., 391, 396-97 (1999-2000). 46 Lester Ross, The Changing Profile of Dispute Resolution in Rural China: The Case of Zouping County, Shandong, 26 Stan. J. Int’l L., 15, 16 (1989-90). 47 Id. at 16 (quoting Confucius, The Analects 2.3, 12.13). 48 Akigoro Taga, Sofu no kenkyu (1960). 49 Stanley Lubman,Mao and Mediation: Politics and Dispute Resolution in Communist China, 55 Calif. L. Rev.1284, 1298 (1967) (quotingM. Yang, A Chinese Village: Taitou, Shantung Province165-66 (1945)). 50 Wang Daokun,The Biography of Zhu Jiefu,in Chinese Civilization: A Sourcebook219 (Patricia B. Ebrey, ed., 1993). 51 See Kaufmann-Kohler & Kun, supra note 23. 52 For a full discussion, see Shahlla F. Ali, Resolving Disputes in the Asia-Pacific Region: International Arbitration and Mediation in East Asia and the West (2010). 53 See Buhring-Uhle, supra note 18. 54 See generally Ali, supra note 22. 55 Survey questions based on those developed by Buhring-Uhle. Buhring-Uhle, supra note 18. 56 See Int’L Bar Ass’n, supra note 38. 57 Survey questions based on those developed by Buhring-Uhle. Buhring-Uhle, supra note 18. 58 See Int’l Bar Ass’n, supra note 38. 59 Interview No. 22 with Chinese arbitrator. © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 17 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 10/4/2011 For Educational Use Only THE MORALITY OF CONCILIATION: AN EMPIRICAL..., 16 Harv. Negot. L. Rev. 1 60 Interview No. 10 with member of Chinese arbitration commission, in Beijing, China (Nov. 28, 2006). 61 See Int’l Bar Ass’n, supra note 38. 62 See Buhring-Uhle, supra note 18. 63 Survey questions based on those developed by Buhring-Uhle. Buhring-Uhle, supra note 18. 64 See Int’l Bar Ass’n, supra note 38. 65 Interview No. 42 with Chinese attorney, in Hong Kong, China (Dec. 3, 2006). 66 Interview No. 59 with Chinese attorney, in Hong Kong, China (Dec. 3, 2006). 67 Interview No. 3 with East Asian Arbitrator, Chinese Representative to UNCITRAL, in Kuala Lumpur, Malay. (Nov. 22, 2006). 68 Interview No. 59 with Chinese attorney, in Hong Kong, China (Dec. 3, 2006). 69 Interview No. 23 with Chinese arbitrator, in Beijing, China (Nov. 28, 2006). 70 Id. 71 Interview No. 10 with member of Chinese arbitration commission, in Beijing, China (Nov. 28, 2006). 72 Interview No. 3 with East Asian Arbitrator, Chinese Representative to UNCITRAL, in Kuala Lumpur, Malay. (Nov. 22, 2006). 73 Id. 74 Id. 75 Interview No. 23 with Chinese arbitrator in Beijing, China (Nov. 28, 2006). 76 Interview No. 22 with Chinese arbitrator in Beijing, China. (Nov. 28, 2006). 77 Interview No. 11 with attorney working in China, in Beijing, China (Nov. 28, 2006). 78 Interview No. 30 with attorney working in Hong Kong, in Hong Kong, China (Dec. 3, 2006). 79 See Int’l Bar Ass’n, supra note 38. © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 18 WILLIAM GOLDMAN 10/4/2011 For Educational Use Only THE MORALITY OF CONCILIATION: AN EMPIRICAL..., 16 Harv. Negot. L. Rev. 1 80 See, e.g., William Twining, Have Concepts, Will Travel: Analytical Jurisprudence in a Global Context, 1 Int’l J. of L. in Context 5 (2005). 81 See generally Philip Selznick, The Moral Commonwealth: Social Theory and the Promise of Community (1992). End of Document © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. © 2011 Thomson Reuters. No claim to original U.S. Government Works. 19