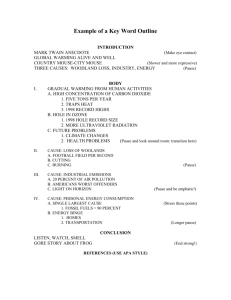

c. bahasa inggris untuk tujuan instruksional

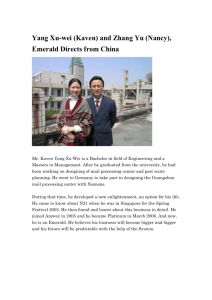

advertisement