Habib & Scotti - School of Computer Science and Statistics

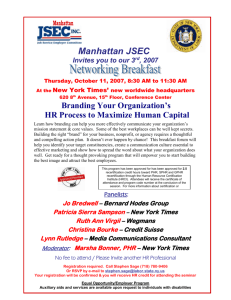

advertisement